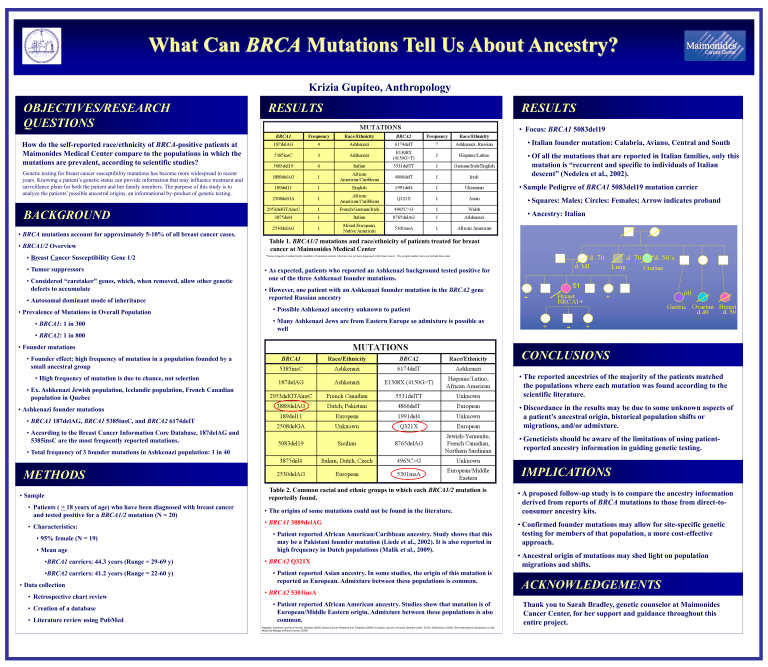

What Can BRCA Mutations Tell Us About Ancestry? Krizia Gupiteo

What Can BRCA Mutations Tell Us About Ancestry?

OBJECTIVES/RESEARCH

QUESTIONS

How do the self-reported race/ethnicity of BRCA-positive patients at

Maimonides Medical Center compare to the populations in which the mutations are prevalent, according to scientific studies?

Genetic testing for breast cancer susceptibility mutations has become more widespread in recent years. Knowing a patient’s genetic status can provide information that may influence treatment and surveillance plans for both the patient and her family members. The purpose of this study is to analyze the patients’ possible ancestral origins, an informational by-product of genetic testing.

BACKGROUND

• BRCA mutations account for approximately 5-10% of all breast cancer cases.

•

BRCA1/2 Overview

•

Breast Cancer Susceptibility Gene 1/2

•

Tumor suppressors

• Considered “caretaker” genes, which, when removed, allow other genetic defects to accumulate

•

Autosomal dominant mode of inheritance

• Prevalence of Mutations in Overall Population

•

BRCA1: 1 in 300

•

BRCA2: 1 in 800

•

Founder mutations

•

Founder effect: high frequency of mutation in a population founded by a small ancestral group

•

High frequency of mutation is due to chance, not selection

• Ex. Ashkenazi Jewish population, Icelandic population, French Canadian population in Quebec

• Ashkenazi founder mutations

•

BRCA1 187delAG, BRCA1 5385insC, and BRCA2 6174delT

•

According to the Breast Cancer Information Core Database, 187delAG and

5385insC are the most frequently reported mutations.

•

Total frequency of 3 founder mutations in Ashkenazi population: 1 in 40

METHODS

• Sample

•

Patients ( > 18 years of age) who have been diagnosed with breast cancer and tested positive for a BRCA1/2 mutation (N = 20)

•

Characteristics:

•

95% female (N = 19)

•

Mean age

•

BRCA1 carriers: 44.3 years (Range = 29-69 y)

• BRCA2 carriers: 41.2 years (Range = 22-60 y)

•

Data collection

•

Retrospective chart review

• Creation of a database

•

Literature review using PubMed

Krizia Gupiteo, Anthropology

RESULTS

Table 1. BRCA1/2 mutations and race/ethnicity of patients treated for breast cancer at Maimonides Medical Center

*Some categories include family members of mutation carriers who have not yet been diagnosed with breast cancer. The sample number does not include these data.

• As expected, patients who reported an Ashkenazi background tested positive for one of the three Ashkenazi founder mutations.

• However, one patient with an Ashkenazi founder mutation in the BRCA2 gene reported Russian ancestry

• Possible Ashkenazi ancestry unknown to patient

•

Many Ashkenazi Jews are from Eastern Europe so admixture is possible as well

Table 2. Common racial and ethnic groups in which each BRCA1/2 mutation is reportedly found.

• The origins of some mutations could not be found in the literature.

•

BRCA1 3889delAG

•

Patient reported African American/Caribbean ancestry. Study shows that this may be a Pakistani founder mutation (Liede et al., 2002). It is also reported in high frequency in Dutch populations (Malik et al., 2009).

•

BRCA2 Q321X

•

Patient reported Asian ancestry. In some studies, the origin of this mutation is reported as European. Admixture between these populations is common.

•

BRCA2 5301insA

• Patient reported African American ancestry. Studies show that mutation is of

European/Middle Eastern origin. Admixture between these populations is also common.

Citations: American Journal of Human Genetics (2002); Breast Cancer Research and Treatment (2009); European Journal of Human Genetics (2002, 2010); Smithsonian (2008); Third International Symposium on the

Molecular Biology of Breast Cancer (2005)

RESULTS

•

Focus: BRCA1 5083del19

•

Italian founder mutation: Calabria, Aviano, Central and South

•

Of all the mutations that are reported in Italian families, only this mutation is “recurrent and specific to individuals of Italian descent” (Nedelcu et al., 2002).

•

Sample Pedigree of BRCA1 5083del19 mutation carrier

•

Squares: Males; Circles: Females; Arrow indicates proband

•

Ancestry: Italian

CONCLUSIONS

•

The reported ancestries of the majority of the patients matched the populations where each mutation was found according to the scientific literature.

•

Discordance in the results may be due to some unknown aspects of a patient’s ancestral origin, historical population shifts or migrations, and/or admixture.

•

Geneticists should be aware of the limitations of using patientreported ancestry information in guiding genetic testing.

IMPLICATIONS

•

A proposed follow-up study is to compare the ancestry information derived from reports of BRCA mutations to those from direct-toconsumer ancestry kits.

•

Confirmed founder mutations may allow for site-specific genetic testing for members of that population, a more cost-effective approach.

•

Ancestral origin of mutations may shed light on population migrations and shifts.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Thank you to Sarah Bradley, genetic counselor at Maimonides

Cancer Center, for her support and guidance throughout this entire project.