Williams` Integrity: Is The Utilitarian`s Calculus Too Inhuman

advertisement

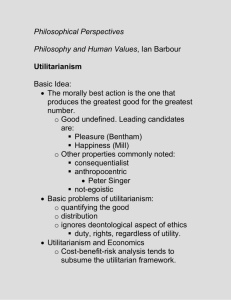

Williams’ Integrity: Is The Utilitarian’s Calculus Too Inhuman for Morality? Alexander Raby Introduction Bernard Williams’ article "A Critique of Utilitarianism" has been consistently referred to as the definitive work that refutes utilitarianism.1 In this article, Williams builds an argument against consequentialist ethical theories in general and utilitarianism specifically. According to Williams, all forms of consequentialism are concerned solely with consequences and are indifferent to the personal integrity of a person, something that is formed by their deepest held moral principles.2 By forcing a person to reject her conscience and compelling her to perform lesser evils, utilitarianism requires us to discard integrity and should be rejected on these grounds, or at least so says Williams.3 It can be difficult to understand Williams’ argument without making clear the charges he makes against utilitarianism and why they are considered to be effective attacks against the view. To get the clearest conception possible of the charges made, one should have a firm grasp of the utilitarian position so that one may successfully relate Williams’ criticisms to the theory. First, the utilitarian moral theory must be clearly formulated. Then I will present and clarify some of Williams’ objections against this theory. Finally, I will explore some utilitarian responses to Williams’ objections. 1 See Sneddon, “Feeling Utilitarian,” Utilitas 15, no. 3 (2003): 330; Ashford, "Utilitarianism, Integrity, and Partiality," The Journal of Philosophy 97, no. 8 (2000): 421; Lenman, “Utilitarianism and Obviousness,” Utilitas 16, no. 3 (2004): 322; Smart, Utilitarianism: For and Against. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1973: 77-180; Braybrook, Utilitarianism: Restorations; Repairs; Renovations. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2004: 81. Michael Stocker and Bernard Williams are claimed by Sneddon to be “particularly important” proponents of the argument that utilitarianism’s alienation, a central point in Williams’ article, is an influential reply to utilitarianism. Ashford also claims the integrity objection to be highly influential. Lenman, in his introductory excerpt of his article, claims that the purported counterexample of Jim and the Indians, proposed by Bernard Williams, is highly influential and claims it is one of the most discussed examples in contemporary moral philosophy. Baybrook refers to Williams’ Jim and the Indians thought experiment as “famous.” 2 Smart, 94. 3 Ibid. 1 Articulating Utilitarianism Utilitarianism is a moral theory that is traditionally attributed to Jeremy Bentham and John Stuart Mill.4 In his essay An Introduction to the Principles of Morals and Legislation, Bentham illustrates his view on the notion of utility by stating at the very beginning that: Nature has placed mankind under the governance of two sovereign masters, pain and pleasure. It is for them alone to point out what we ought to do, as well as to determine what we shall do.5 He goes on to explain that utility itself is the grand decider of all actions, stating: By the principle of utility is meant that principle which approves or disproves of every action whatsoever, according to the tendency it appears to have to augment or diminish the happiness of the party whose interest is in question.… An action may be said to be conformable to the principle of utility when the tendency it has to augment the happiness of the community is greater than any it has to diminish it.6 John Stuart Mill expands this notion into a more developed one in the construction of his own theory in his book entitled Utilitarianism. In it, he explains the role of pleasure and pain and how those concepts form the nucleus of the utilitarian ethical theory. The creed which accepts as the foundation of morals, Utility, or the Greatest Happiness Principle, holds that actions are right in proportion as they tend to 4 Rosen, Classical Utilitarianism from Hume to Mill. Routledge, 2003: 28. "It was Hume and Bentham who then reasserted most strongly the Epicurean doctrine concerning utility as the basis of justice." 5 Bentham, An Introduction to the Principles of Morals and Legislation. Oxford:Clarendon Press, 1789: 1. 6 Ibid., 2. 2 promote happiness, wrong as they tend to produce the reverse of happiness. By happiness is intended pleasure, and the absence of pain; by unhappiness, pain, and the privation of pleasure. To give a clear view of the moral standard set up by the theory, much more requires to be said; in particular, what things it includes in the ideas of pain and pleasure; and to what extent this is left an open question. But these supplementary explanations do not affect the theory of life on which this theory of morality is grounded- namely, that pleasure, and freedom from pain, are the only things desirable as ends; and that all desirable things (which are as numerous in the utilitarian as in any other scheme) are desirable either for the pleasure inherent in themselves, or as means to the promotion of pleasure and the prevention of pain.7 The “Greatest Happiness Principle” is presented as the core of morality according to Mill. It is this principle that serves as the foundation for utilitarianism. Still, for the purposes of this essay, the principle will require some further refining. This refinement must maintain the spirit of the principle while providing some clarity that may not be immediately apparent in Mill’s quotation without the aid of supplementary explanation. U: An act A is morally right iff no other alternative to A would produce a greater balance of pleasure over pain than A would. When articulated in this way, one can see how the theory is meant to operate. First, it avoids the pitfall of trying to maximize two independent variables. It combines pleasure and pain into a calculation known as “hedonic utility,” which is the result of subtracting the amount of pain an act would produce for the world from the amount of pleasure that act would produce for the world. Second, it also accommodates the “ties at the top” 7 Mill, Utilitarianism. London: Navill, Edwards, and Co., Printers, 1871: 1. 3 phenomenon because it does not demand that there be a single alternative that has a highest hedonic utility. A “ties at the top” case is said to occur when at least two alternatives have equal hedonic utility with no available alternative possessing a higher hedonic utility than they do. The definition employed in this paper implies that either would be morally acceptable, and thus no conflict arises. A typical utilitarian scenario has a specific conceptual form. An agent has several alternatives A1, A2, A3, A4, and A5. For each alternative, begin by calculating the utility for the agent, then calculate the utility for the rest of the world; finally, sum the numbers. The result is the total hedonic utility of the alternative. Following this method, consider the following utilities for A1-A5: A1) HU= 100 A2) HU= 50 A3) HU= 50 A4) HU= -25 A5) HU= -50 In this abstract case, A1 is the morally right answer on the utilitarian scheme, while its alternatives are morally wrong because they fail to produce the greatest possible balance of pleasure over pain for the world. If A1 were eliminated from the case, then either A2 or A3 would be permissible without any problem (a “ties at the top” scenario). If A4 and A5 were the only options open to the agent, utilitarianism would deliver the classic “lesser of evils” response, implying that A4 is the morally acceptable alternative despite the fact that only negative outcomes could result. Williams’ Opening Attacks 4 Now that utilitarianism has been made clear, we may move to examine Williams’ unique objection to this style of ethical reasoning. Williams attempts to reconcile ethical behavior with our feelings and emotional responses to moral problems. Any ethical theory that fails to do this should not be rated as an acceptable ethical theory. Williams argues, near the end of his essay, that: …[utilitarianism] runs against the complexities of moral thought: in some part because of its consequentialism, in some part because of its view on happiness and so forth. A common element in utilitarianism’s showing in all these respects, I think, is a great simple mindedness.8 Williams goes on to say that what he means by simple mindedness is that utilitarianism recognizes too few thoughts and feelings that reflect the world the way it actually is, both in the way it appears, and the way people go about their lives.9 This is not to say that utilitarianism doesn’t recognize them at all, but it requires that we grant them no special treatment. According to utilitarianism, the way others feel or act in certain situations may force us to act against our own feelings.10 Williams claims that: …our moral relation to the world is partially given to us by such feelings, and by a sense of what we can and cannot ‘live with,’ to come to regard those feelings from a truly utilitarian point of view, that is to say, as happenings outside one’s moral self, is to lose one’s sense of moral identity; to lose, in the most literal way, one’s integrity.11 What is Integrity? 8 9 10 11 Smart, 149. Ibid. Ibid., 103-104. Ibid. 5 The concept of integrity seems to play a key role in Williams’ rejection of utilitarianism, but it is unclear from his article exactly what integrity is supposed to mean. Elizabeth Ashford suggests that integrity is meant to be understood in the classic sense of “wholeness” or a unified sense of self. Adherence to integrity, with this understanding, will mean that some moral feelings serve as a constraint or limitation on what an acceptable moral theory can demand.12 They are not to be simply disregarded on such a view. They create a “moral self-conception,” which, Ashford suggests, is what is preserved by maintaining your integrity.13 However, we must not make the mistake of interpreting a moral self-conception merely as a coherent self conception that happens to include moral feelings. These feelings must not be the result of the agent being seriously deceived or detached from reality. It must be grounded in her leading an actually morally decent life. This kind of integrity is called “objective integrity.” To maintain this integrity, we must abide by our moral commitments and these commitments must stem from moral obligations we have in reality.14 This integrity is seen to be the central guiding point of morality for Williams, and utilitarianism would have us disregard it. This is why we must, it is argued, disregard utilitarianism. Williams’ claim is that utilitarianism is not a complete theory that encompasses how actual acts of morality are performed; thus, it is not grounded realistically.15 For example, utilitarianism fails to recognize the (alleged) moral nuances associated with someone attempting to force you by threats. Williams claims that you can’t always be held responsible for the actions of others, and your moral responsibilities 12 13 14 15 Ashford, 423. Ibid., 422. Ibid., 425. Cf. Ibid., 150. 6 should not be held hostage by the threats others make.16 Utilitarianism, on the other hand, entails that there is no limit to the harm we are permitted to cause in efforts to stave off worse things that others threaten to do. It is the concept of negative responsibility, the idea that you are just as responsible for the things you indirectly cause or fail to prevent as for the things you directly cause, that allows for this kind of hostage taking. Williams rejects this concept by claiming that you have an obligation to, in a sense, make sure that your hand plays no part in the performance of ‘bad’ acts, regardless of what others may threaten. To illustrate both of these points, he uses two thought experiments that are designed to show how we would be mistaken to disregard our integrity. The first case involves George, our agent, and chemical weapons development. The First Test Case: George and the Chemical Weapons George, who has just taken his Ph.D. in chemistry, finds it extremely difficult to get a job. He is not very robust in health, which cuts down the number of jobs he might be able to do satisfactorily. His wife has to go out to work to keep them, which itself causes a great deal of strain, since they have small children and there are severe problems about looking after them. The results of all this, especially on the children, are damaging. An older chemist, who knows about this situation, says that he can get George a decently paid job in a certain laboratory, which pursues research into chemical and biological warfare. George says that he cannot Smart, 109. Williams says that “If the captain had said on Jim’s refusal, ‘you leave me with no alternative’, he would have been lying, like most who use that phrase. While the deaths, and the killing, may be the outcome of Jim’s refusal, it is misleading to think, in such a case, of Jim having an effect on the world through the medium (as it happens) of Pedro’s acts; for this is to leave Pedro out of the picture in his essential role of one who has intentions and projects, projects for realizing which Jim’s refusal would leave an opportunity.” 16 7 accept this, since he is opposed to chemical and biological warfare. The older man replies that he is not too keen on it himself, come to that, but after all George’s refusal is not going to make the job or the laboratory go away; what is more, he happens to know that if George refuses the job, it will certainly go to a contemporary of George’s who is not inhibited by any such scruples and is likely if appointed to push along the research with greater zeal than George would. Indeed, it is not merely concern for George to get the job… George’s wife, to whom he is deeply attached, has views (the details of which need not concern us) from which it follows that at least there is nothing particularly wrong with research into CBW. What should he do?17 The Second Test Case: Jim and the Indians The second example is the case of Jim and the Indians: Jim finds himself in the central square of a small South American town. Tied up against the wall are a row of twenty Indians, most terrified, a few defiant, in front of them several armed men in uniform. A heavy man in a sweat-stained khaki shirt turns out to be the captain in charge and, after a good deal of questioning of Jim which establishes that he got there by accident while on a botanical expedition, explains that the Indians are a random group of inhabitants who, after recent acts of protest against the government, are just about to be killed to remind other possible protestors of the advantages of not protesting. However, since Jim is an honoured visitor from another land, the captain is happy to offer him a guest’s privilege of killing one of the Indians himself. If Jim accepts, then as a special mark of the occasion, the other Indians will be let off. Of course, if Jim 17 Ibid., 97-98. 8 refuses, then there is no special occasion, and Pedro here will do what he was about to do when Jim arrived, and kill them all. Jim, with some desperate recollection of schoolboy fiction, wonders whether if he got hold of a gun, he could hold the captain, Pedro and the rest of the soldiers to threat, but it is quite clear from the set-up that nothing of that kind is going to work: any attempt at that sort of thing will mean that all the Indians will be killed and himself. The men against the walls, and the other villagers, understand the situation and are obviously begging him to accept. What should he do?18 How does Williams Utilize These Cases? The main structure of both examples is clear. The agent is faced with a choice, either to perform act A or not to perform act A. The agent may want to refuse to perform act A because a consequence of performing it includes the introduction of some amount of evil or badness into the world. Additionally, the agent may feel that the performance of A is wrong in principle. If she does refuse to perform A, however, then the consequences that result from her refusal will be even worse than if the agent had performed A. Utilitarianism requires agents to secure the “lesser of evils” in all circumstances of this sort, disregarding how the agent’s principles may conflict with the performance of and participation in the task. First Angle of Attack: Numerical Superiority In all of these sample cases, utilitarianism will demand that the agent choose to act in a way that is guided primarily by the feelings of others over his own because their 18 Ibid. 9 unhappiness is collectively greater than his. Williams says that this is an unacceptable scenario. It is absurd, in Williams’ view, to disregard the agent’s feelings merely because people who feel contrary to the agent are more numerous; in fact, Williams thinks the agent’s feelings ought to play a larger role in how the agent should act.19 The reluctance to act in a certain way should serve as an indicator as to which of the alternatives is morally permissible, and these feelings should not be discarded so easily simply because of the numerical superiority of the opposition.20 Jim and George, in the thought experiments, are faced with the numerical superiority of those whose lives they might save. In the test cases, the number of people who would ask that Jim and George abandon their moral convictions —so that the greater populace might preserve their own goals—outnumbers those who would support them. To the utilitarian, even if there were no lives at stake, the simple fact that more would be displeased than pleased if Jim and George were to act in accordance with their moral feelings is reason enough to ignore them. Williams is adamant that our feelings are indicators of what is right and wrong, and utilitarianism would have us discard those feelings, with which we would intuitively agree, solely because of the greater numbers of the opposition and not because of the nature of the act itself or how we feel about it. That utilitarianism does this too often is an indicator that the theory is problematic, or so Williams suggests.21 Rather than having the morality of certain actions generated from the integrity and character of the agent, the moral statuses of actions, instead, are 19 Ibid., 104. Ibid., 105. 21 Ibid., 107. Williams says that calculations of the effect must be realistic about how people actually think and operate, which is why he believes that discounting ‘squeamishness’ is the reason utilitarianism fails. 20 1 0 determined for the agent by the state of the world. How the agent thinks and feels in these situations plays too small a role according to Williams. Second Angle of Attack: Negative Responsibility is Too Strong A second angle from which Williams attacks concerns negative responsibility. Utilitarianism entails that Jim and George are both morally responsible for what they fail to prevent and allow others to perform. Utilitarianism does not grant any special moral status to the fact that both of these men are forced into a situation by the actions of others: if Jim does not kill the one Indian, then he will become responsible for the deaths of the other nineteen. A utilitarian evaluation ignores the fact that Pedro is the one who performs these acts of killing and not Jim. Williams suggests that it is a mistake to hold Jim responsible for Pedro’s actions and that the true culprit of their deaths is Pedro alone. Jim’s only responsibility, according to Williams, is to make sure that his hand does not take part in immoral acts: Pedro’s actions will be Pedro’s moral responsibility, and nothing about the situation will make Jim responsible for them if it is Pedro performing the acts. 22 Third Angle of Attack: Integrity The final attack from Williams’ essay concerns the importance of integrity to the life of the agent. Utilitarianism will require that the agent refrains from giving any special weight to his own personal projects solely in virtue of those projects being his. Suppose that Jim has a personal project of refraining from killing any innocent people, and recall that George has a personal project of refraining from engaging in biological and chemical weapons research. According to the utilitarian, if Jim were to feel badly for shooting the Ibid., 109. Williams says: “That may be enough for us to speak, in some sense, of Jim’s responsibility for that outcome, if it occurs; but it is certainly not enough, it is worth noticing, for us to speak of Jim’s making those things happen.” 22 1 1 Indian or George for participating in chemical and biological weapons research, then to act favorably towards these negative feelings and refuse to act would amount to self indulgent squeamishness. George could have saved his family from starvation and Jim could have saved nineteen Indians. If they were to refuse, it would have been because it would have made them feel bad. Utilitarianism asks you to distance yourself from your feelings and projects in a plethora of cases. For Williams, to demand this is contradictory, since you are your feelings and they make you who you are. Everyone has projects and commitments that they wish to pursue. Williams claims that these projects are integral to who you are.23 This is a different charge from the first one discussed. Earlier, it was suggested by Williams that the numerical superiority of the opposition should not be the determining element of whether certain acts are morally permissible or not. In this objection, we are asked to focus upon the importance of the agent following through with his commitments and, in failing to do so, the possibility of being harmed. In the case of Jim and the Indians, utilitarianism requires that Jim ought to drop his project not to kill any innocent people in light of Pedro’s projects, ignoring his own desire not to be part of an innocent killing. To deny these commitments and moral feelings that one has spent a lifetime building up, is to deny what is essential to being a moral person. This is your integrity. On Williams’ view, to live in a way that is in accordance with your moral integrity is too valuable to give up.24 Ibid., 116-117. “How can a man, as a utilitarian agent, come to regard as one satisfaction among others, and a dispensable one, a project or attitude round which he has built his life, just because someone else’s projects have so structured the causal scene that that is how the utilitarian sum comes out?” 24 Ibid. 23 1 2 In addition, the utilitarian desire to discard such commitments for the benefit of the hedonic calculus may rob the agent of a flourishing life. To illustrate this, imagine a scenario in which our agent, Anna, considers three possible paths for her life to follow before her. In life A, Anna leads a life with a great career and personal relationships but gives nothing to charity or to help alleviate other people’s suffering. In life B, Anna gives a considerable amount to charity but still leads a moderately pleasurable personal life. In life C, she follows a life similar to that of Mother Theresa, the whole of her time dedicated to suffering people, thinking nothing for herself or her wants. On the assumption that living life C would usher into the world the greatest possible balance of pleasure over pain, utilitarianism requires Anna to choose C as the morally worthwhile life. It is this sacrifice of self and of one’s own personal desires and commitments that brings harm to the agent —unnecessarily so on Williams’ view.25 Utilitarian Responses In response to the first charge leveled by Williams—that of numerical superiority—it is not clear that utilitarianism always requires following the whims of the most numerous groups. There are many possible scenarios where the good utilitarian will find herself acting in favor of the minority, especially in cases where favoring the minority group would—in the long run—be most beneficial for the world as a whole. It is true, however, that utilitarians believe that personal sacrifices are necessary in order to serve the greater good. Utilitarianism does not necessarily require that ease or comfort always be enjoyed by the agent of the act; instead, it implies that the lives of anyone within causal range of the agent be improved to the greatest possible degree (from an overall perspective), regardless of whether or not the agent herself is benefitted by the act. The whole conflict 25 Ashford, 428. 1 3 Williams describes is not one of numbers alone, but that, all things being equal, there are more lives that can be saved by one action than another. This is not, however, a tyranny of the masses but an adherence to the greatest good. In Williams’ account, the greater good rarely plays a part in his consideration, and he seems preoccupied by the state of the agent, particularly with his ability to “live with” his actions. Until an account for the role the “greater good” ought to play in determining the moral statuses of acts is provided, Williams’ account will remain incomplete. Note that in another piece by Williams, he does mention that morality would require someone to act to benefit those who are considered to be in an “emergency situation.”26 If Williams believes that this obligation holds true regardless of geographical distance, given the capabilities of modern technology, then it would seem an agent’s integrity runs the risk of being eroded by the constant state of people’s emergencies around the world. If Williams is correct in this account of obligation, then it seems to be inconsistent with his criticism of utilitarianism, since they both appear to demand that the agent set aside his personal projects and commitments to act on behalf others. A utilitarian may respond to Williams’ rejection of negative responsibility (his second angle of attack) by examining the nature of moral obligation even further. The basis for Williams’ rejection of negative responsibility is that actions performed by other agents are not the responsibility of the primary agent. Pedro’s actions are Pedro’s responsibility. But in other writings, Williams’ account of obligation involves being required to help those people in emergency situations, including those who are geographically and socially distant from the agent.27 What Williams seems to be saying about negative 26 27 Williams, Ethics and the Limits of Philosophy. Cambridge: Harvard, 1985: 185-186. Ibid. 1 4 responsibility is that it unfairly makes the agent responsible for the failures of others to act morally and should be rejected on the grounds of this unfairness. However, the claim of unfairness is obviously outweighed by the pleas of people whose lives would be saved by a choice to act on their behalf.28 This unfairness is irrelevant in this case, as a utilitarian would still claim that this does not alleviate an agent’s responsibility to act for the greater good. Additionally, it seems odd that the presence of Pedro, as another agent, is presented as a possible excuse to keep Jim from having to act to save the Indians. We can compare Jim’s case to a modified version of the trolley thought experiment. Judy Jarvis Thomson proposes a similar “trolley” thought experiment in her influential article “Killing, Letting Die, and the Trolley Problem.”29 Imagine that a trolley is running out of control on the track. The conductor, who is a friend of Jim’s, contacts him by radio and informs him that the trolley cannot stop. He also tells him that if the trolley continues down the track, it will crash into a group of twenty people socializing near the end of the track. To prevent this, Jim could pull the track lever, causing the trolley to switch to another track. However, doing so will still result in the death of at least one bystander who is walking along that track. Without time to warn any of the people on the tracks, Jim must decide to pull the switch or not. If Jim fails to act to save the bystanders, he takes the blame in the absence of other agents. Nothing about Jim’s personal projects or integrity could justify his inaction. Yet, Jim’s alternatives in this scenario are nearly identical to the ones involving Pedro. Preserving your integrity, it seems, is only a concern when you have others to blame. Meanwhile, in George’s case, what valuable moral ground has he 28 29 Cf. Ashford, 433. Thomson, "Killing, Letting Die, and the Trolley Problem," The Monist 59, (1976): 204-17. 1 5 preserved that is more important than the lives he has saved? Will having his wife and child starve to death make him feel better than if he worked on biological weapons? The final charge of integrity seems to be related to the question of whether or not utilitarianism is too demanding. By requiring the agent to abandon his moral self conception, it strips him from his humanity and identity. Williams may have been poetic in portraying it this way, as it is difficult to imagine that what one accepts as moral norms is essential to one’s identity in some literal way. There are many times when one may shed whole sets of beliefs and may arguably still be the same person. It is even more troublesome, however, to believe that what makes you moral or immoral is adherence to a set of feelings. Williams does not question where one obtains these sorts of moral beliefs; he merely suggests that they are important because they were built up over a lifetime. This seems to imply that those who grew up in a pro-Nazi family or as a racist slave owner ought to struggle as hard as they can not to be swayed by the lives and pleas of other human beings for fear of having their integrity tainted. The Nazi and the philanthropist may differ on the content of their moral feelings, but the sensation of these “moral feelings” may be identical. Williams does not suggest how we may be able to discriminate true moral feelings from misguided ones. Societal norms determine many people’s moral self-conceptions, and this in turn will become part of their integrity, as formulated by Williams. Obviously, we would require that the slave owner and the Nazi question their moral feelings about these beliefs and, hopefully, be guided away from them. An appeal for them to remain true to their integrity, lifelong projects, or moral self conceptions would only drive them deeper into their harmful beliefs.30 That utilitarianism would require them to question this and run contrary to their moral feelings is, perhaps, 30 Cf. Ibid,. 423-424. 1 6 more a benefit than a blemish. In the end, the utilitarian may claim that many moral feelings are of dubious origin, and it is doubtful that they are the result of any intuitive and truthful grasp of what is moral and what is not.31 As a result, they are unreliable (or at least questionable) in matters of morality. Bibliography Ashford, Elizabeth. "Utilitarianism, Integrity, and Partiality." The Journal of Philosophy 97, no. 8 (2000): 421-439. (KILL ALL COMMAS IN BIB) Bentham, Jeremy. An Introduction to the Principles of Morals and Legislation. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1789. Baybrook, David. Utilitarianism: Restorations; Repairs; Renovations. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2004. Lenman, James. "Utilitarianism and Obviousness." Utilitas 16, no. 3 (2004): 322-325. Mill, John S. Utilitarianism. London: Navill, Edwards, and Co., Printers, 1871. Rosen, Frederick. Classical Utilitarianism from Hume to Mill. Routledge, 2003. 31 Ibid. 1 7 Smart, John Jamieson Carswell, and Bernard Williams. Utilitarianism: For and Against. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1973. Sneddon, Andrew. "Feeling Utilitarian." Utilitas 15, no. 3 (2003): 330-352. Thomson, Judith Jarvis. "Killing, Letting Die, and the Trolley Problem." The Monist 59, (1976): 204-17. Williams, Bernard. Ethics and the Limits of Philosophy Cambridge: Harvard, 1985. 1 8