Psychological Contracts: why do they matter?

Richard Hall

Associate Professor in Work and Organisational Studies

University of Sydney

Theories of organisational behaviour suggest that a psychological contract between an

employee and an organisation will emerge and develop in virtually every employment

relationship. Given that these psychological contracts consist of the expectations that

employees, in particular, will have of their employing organisation (and its managers),

it is evidently important that managers are at least aware of the existence of these

contracts and recognise that employees have legitimate expectations relating to how

they are treated at work. Psychological contracts are normally thought to be important

because their breach has been found to lead to serious consequences, which are

discussed fully below. Thus, it is vital that managers understand, manage and work to

fulfil and sustain psychological contracts if these adverse consequences are to be

avoided.

Although most research attention has been paid to the effects of breaching

psychological contracts rather than the effects of fulfilling those contracts, it is

normally thought that highly committed, satisfied and engaged employees will have a

relatively strong and generally fulfilled psychological contract with their organisation

(Guest and Conway 2002). Therefore we can conclude that strong, positive and

fulfilled psychological contracts, especially those of the relational variety, will tend to

contribute positively to employee motivation and performance. This raises the

question of how managers can manage these contracts.

Establishing and managing the psychological contract

Relatively little research has been undertaken into the implications of psychological

contracts for management. However on the basis of research undertaken to date it is

possible to identify some likely implications.

Making the terms of psychological contracts explicit

Given that psychological contracts are implicit, potentially complex and inherently

subjective it has been suggested that organisations (and employees) should make the

terms of these contracts more explicit so that there is less chance of breaches being

caused by misunderstanding. This suggests the need for open and honest discussions

between management and employees concerning their mutual expectations and

perceptions of promises and obligations. It also suggests a role for ‘realistic job

previews’, comprehensive induction programs, wide-ranging performance and

development meetings and regular feedback.

While there are few downsides to improved communication at work between

employers and employees, leaving some elements and aspects of the employment

relationship unstated may be functional and advantageous for employers and

employees. Seeking to render explicit all aspects of the mutual obligations between

the parties might serve to restrict the room to manoeuvre, in which employees can

1

exercise discretion and autonomy, and in which managers and supervisors can tolerate

and accommodate the inevitable diversity of employee needs and preferences. The

reality probably is that in instances where implicit rules are rendered explicit, the

superior power and authority of management will typically result in the assertion of

managerial prerogative over employee aspirations.

Managing changes to the psychological contract

Organisations (and their managers) need to recognise that organisational changes will

often imply changes to the psychological contract even if they don’t involve changes

to the formal employment contract and working conditions of employees. This

underlines the importance of organisations, change agents and managers recognising

the need for effective strategies for anticipating, recognising and managing employee

resistance and accommodating the expectations that employees might have. Common

strategies for managing employee resistance to change centre on the following

(Brown and Harvey 2006):

-

Education and communication concerning the need for change

Creating and reinforcing the vision of where the organisation is headed

Ensuring participation and involvement of those affected in the change process

Facilitating and supporting change through training and resources

Negotiating with resistors

Use of reward systems to encourage changed behaviours

Use of explicit or implicit coercion

Research into resistance to organisational change suggests that managers need to

understand the reasons for resistance in order to manage it. The psychological

contracts perspective highlights that the reason for resistance might be associated with

a perceived breach to the psychological contract. Communication, participation,

negotiation and reward strategies might therefore need to be geared to addressing

those perceived breaches.

Breaching the psychological contract - implications for managers and

organisations

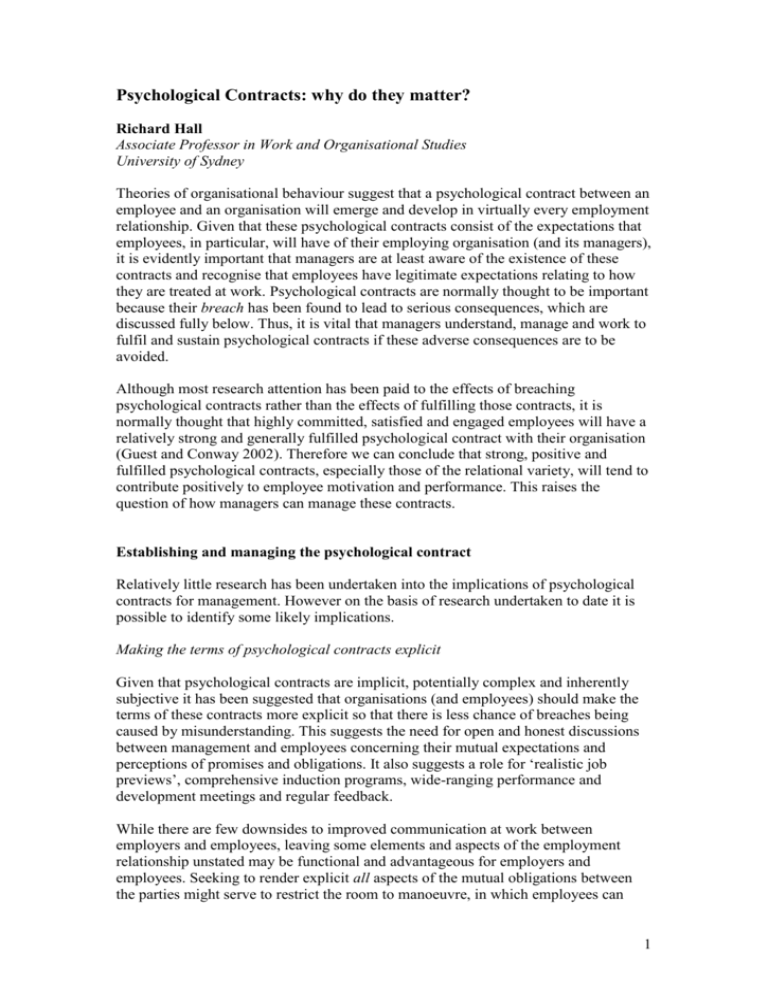

While the place of psychological contracts in models of employee motivation and

performance (which are the mainstay of the discipline of organisational behaviour) is

controversial, the best conclusion is that they probably affect individual employee

attitudes and behaviour (see Figure 1). Psychological contract breach is generally

defined as a perceived discrepancy between the promise and performance (of the

organisation) with respect to one or more terms of the contract. In other words,

according to the employee, the organisation ‘fails to meet its side of the deal’.

The weight of research indicates that instances of psychological contract breach tends

to affect both employee attitudes and behaviours, although the effect is significantly

more pronounced on attitudes than behaviours. In particular, breaches in the

psychological contract have been found to be associated with the following attitudes:

lower levels of job satisfaction;

2

lower levels of organisational commitment; and

a greater intention to quit.

Breaches have also been associated with several dimensions of adverse employee

behaviour:

higher quit rates;

less propensity to display organisational citizenship behaviour (‘going the

extra mile’ at work); and

lower in-role job performance.

Figure 1: Simplified Model of the Role of the Psychological Contract and

Attitudes and Behaviour

Individual

Characteristics

Organisational

Characteristics,

Policies and

Practices

Attitudes

- Motivation

- Satisfaction

-Commitment

-intention to

quit/ stay

Behaviour

- job

performance

- OCB

- quitting

Results

Psychological Contract

Breaches

Evidently, breaches of the psychological contract can have serious consequences for

employees and, to the extent that organisations might be concerned about retention,

performance and productivity, for organisations as well.

Surveys of employee experiences suggest that breaches are not uncommon. One study

of recent MBA graduates indicated that 55% reported at least one breach of the

psychological contract in their first two years of employment (Robinson and

Rousseau 1994 in Conway and Briner 2005: 65). Methodologies based on employees’

diaries of workplace experience report significantly higher levels of breach – one

study reported that 69% of employees recorded at least one breach in the ten-day

survey period (Conway and Briner 2002 in Conway and Briner 2005: 65). Of course,

not all breaches result in adverse attitudinal or behavioural responses. The implication

of any given breach is likely to be related to the importance of the unmet promise or

obligation, the extent to which the breach is actually attributed to the organisation,

3

and the depth and strength of the existing psychological contract (especially the

relational contract).

The causes of psychological contract breach are also largely a matter of informed

speculation in the absence of a substantial body of systematic research. Conway and

Briner (2005: 65-69) contend that breaches will be caused by:

Management reneging on deals. Here, organisations, acting through the

agency of managers, might simply change the terms of the deal, unilaterally.

Indeed, many instances of organisational change might involve a change to

the psychological contract. For example, organisational restructuring has often

been associated with downsizing which may have implications for promises

regarding job security. This kind of change has been comprehended as a shift

from a relational psychological contract to a transitional psychological

contract (Shields 2007).

Inadequate human resource policies. This is likely to occur where HR policy

and practice does not match HR rhetoric. The organisation’s espoused values

and advertised HR policies might advocate human resource development,

training opportunities, family-friendly work arrangements, career

development and promotional opportunities, however actual work practices

and the operation of performance management systems might result in

escalating performance demands, resource constraints and work

intensification.

Lack of perceived organisational or supervisor support for the employee.

While employees are thought to have their psychological contract with the

organisation, they will inevitably regard their supervisor or manager as

responsible for upholding the deal on a regular basis. The failure of managers

to provide adequate resources, feedback, support or opportunities for

employees may be caused by inadequate resources at their disposal,

managerial incompetence, role misperceptions, or a misunderstanding of the

expectations of the employee.

Misunderstanding of the terms of the psychological contract. Research has

repeatedly shown that employees and managers often have different

perceptions as to the content of psychological contracts, particularly with

respect to the obligations owed by the organisation. If the employee has overestimated the promises made by the organisation, then a perceived breach is

likely even where the organisation believes it is fulfilling its side of the deal.

Conway and Briner (2005) also argue that a specific action by an organisation or

management will be more likely to be perceived as a breach of the psychological

contract where the employee has previously experienced breaches, and where the

employee has relatively good options in the labour market for alternative

employment. Obviously, this last point suggests that breaches will have greater

implications where labour market conditions are relatively tight and where the skills

of focal employees are in short supply.

4

Managing breaches to the psychological contract

If managers can recognise that the psychological contract has been breached, from the

perspective of an employee, what can they do?

Organisations and managers should monitor for breaches. It is likely that many

employees will be able to tolerate breaches up to some ‘tipping point’ at which a

further breach will lead to adverse attitudes and behaviour. Managers therefore might

be able to monitor for breaches so that preventative action might be taken to avert the

adverse consequences of breaches. Conway and Briner (2005) argue that managers

need to be alert to the displayed emotions and behaviours of their employees for signs

of perceived psychological contract breach. They identify frustration, helplessness,

anger and resentment as key displayed emotions that should send warning signals.

Ultimately the capacity of managers to read and interpret these signals will probably

related to their ‘emotional intelligence’ (Goleman 1998).

Organisations and managers can try to redress breaches. Once a breach has occurred

managers can try to redress the situation by: a) explaining the reasons for the breach;

b) compensating for the breach; and/or c) ensuring organisational justice (Conway

and Briner 2005). Evidence for the effectiveness of these strategies is mixed:

explanation appears to make little difference to employees’ ascription of

responsibility to the organisation (Robinson and Morrison 2000); adequate

compensation can apparently ameliorate the damage done by a breach (Conway and

Briner 2005: 173) ; and, organisational justice strategies need to be tailored to the

specifics of the breach to have any effect (Kickul et al 2002).

Are psychological contracts just a managerialist confidence trick?

The concept of the psychological contract directs attention to the individual level by

focussing on the employee’s formation of a set of expectations of employer behaviour

at work. It suggests a scenario where employees then evaluate organisational

behaviour according to the fulfilment or breach of the terms of the implied contract

and predicts that employees will take adverse action against an organisation where

serious breaches occur. It also implies (however imperfectly) that there is something

approximating an equivalence between the two contacting parties: the employee and

the organisation coming together to reach an implicit agreement as to the terms under

which each will fulfil their obligations. Much of the discussion about psychological

contracts also suggests that breaches are often caused by employee’s

misunderstanding the actual terms of the contract, hence the suggestion that

management should clarify the terms of psychological contracts by making them

more explicit.

Some critics (eg: Cullinane and Dundon 2006) have argued that this is a somewhat

fanciful depiction of the contemporary workplace and that the concept of the

psychological contract simply serves to disguise and obscure the true nature of

management power and prerogative at work. Rather than an equivalence between

employee and employer at work, these critics see a structural antagonism between

employers and employees where the former use their superior power to dictate the

explicit and implicit terms and conditions of employment, both formally and

5

informally. They reject the notion that employees aggrieved by a perceived breach to

the psychological contract can simply elect to quit, or otherwise discipline the

organisation through reduced effort and performance. More often than not, they

contend, employees are forced to accept the new terms of the psychological contract

as dictated by management. Further they suggest that organisations routinely and

deliberately breach psychological contracts because they are more committed to

achieving the strategic goals of the business than honouring any implicit contract that

employees might believe they have with them. The case studies noted by Cullinane

and Dundon (2006), for example, certainly demonstrate that breaches are often caused

by deliberate management strategies associated with downsizing, restructuring, reengineering and cost-cutting rather than by employee misinterpretation of the terms of

the psychological contract. It is also difficult to avoid the conclusion that, despite the

rhetoric of ‘high-performance’ and ‘high-involvement’ work systems that should be

associated with longer-term, relational or balanced psychological contracts, the

predominant pattern in western business organisations over the past 20 years has been

a shift in the direction of a greater emphasis on shorter-term, transactional and

transitional psychological contracts.

Conclusion

Ultimately, the rhetoric surrounding the current interest in psychological contracts

needs to be critically considered in light of the realities of workplace change in the

recent past. When managers speak of the need to manage the psychological contract,

as many apparently now do, we need to ask whether they actually mean managing

down the expectations of employees and socialising them into accepting the ‘realities’

of deals that are rather more transactional, short-term and unilateral than relational,

long-term and based on partnership. Nevertheless, if nothing else, the concept of the

psychological contract does remind us that the perceived terms and conditions under

which people work in organisations are considerably more extensive, complex and

subtle than suggested by the formal contract of employment, and that their breach can

have significant consequences for both individuals and organisations.

Websites and Resources

CIPD Factsheet: The psychological contract. (January 2008). This brief overview

of psychological contracts provided by the UK Chartered Institute of Personnel

and Development is useful and can be accessed at

http://www.cipd.co.uk/subjects/empreltns/psycntrct

Grimmer, M. and Oddy, M. (2007) ‘Violation of the Psychological Contract: The

Mediating Effect of Relational Versus Transactional Beliefs’, Australian Journal

of Management, 32(1): 2007. This recent paper presents data based on a study of

Australian MBA students from two Australian universities. It can be downloaded

from:

http://www.agsm.edu.au/eajm/0706/pdf/Paper8_Grimmer_Oddy_June2007.pdf

Baird, M. ‘Three Degrees of Contract’ looks at the legal contract, the

psychological contract and the social contract and considers the relationships

between them in understanding relations at work. It can be accessed at:

http://www.econ.usyd.edu.au/wos/worksite/baird7.html

6

For an example of the use of the psychological contract by a private management

consultancy and development organisation see: Adelphi Associates (UK):

http://www.adelphi-associates.co.uk/html/psychological_contract.html

References

Brown, D. and Harvey, D. (2006) An Experiential Approach to Organization

Development. 7th Edition. New Jersey: Pearson Prentice Hall.

Conway, Neil & Briner, Rob B. (2005) Understanding Psychological Contracts at

Work: A Critical Evaluation of Theory and Research. Oxford: Oxford University

Press.

Cullinane, N. and Dundon, T. (2006) ‘The Psychological Contract: A critical review’

International Journal of Management Reviews 8 (2): 113-129.

Goleman, D. (1998) ‘What makes a leader?’ Harvard Business Review, Nov-Dec: 93102.

Guest, D. and Conway, N. (2002) Pressure at work and the psychological contract.

London: CIPD.

Kickul, J., Lester, S. and Finkl, J. (2002) ‘Promise Breacking during Radical

Organizational Change: Do Justice Interventions Make a Difference?’ Journal of

Organizational Behavior, 23: 469-88.

Robinson, R.L. and Morrison, E.W. (2000) ‘Psychological Contracts and OCB: The

Effect of Unfulfilled Obligations on Civic Virtue Behavior’ Journal of Organizational

Behavior, 16: 289-298.

Shields, J. (2007) Managing Employee Performance and Reward. Cambridge:

Cambridge University Press

7