“PLATO AND GANDHI:

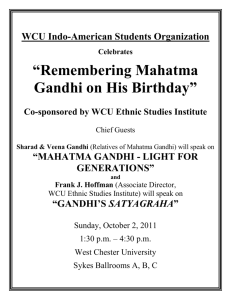

advertisement

HOPE FITZ “PLATO AND GANDHI: JUSTICE AND AHIMSA” (An examination and a comparison of Plato’s and Gandhi’s most fundamental virtues; how these virtues were influenced by their respective epistemes; and why these virtues are necessary for a democratic culture, or nation – state) My keen interest in the topic of this paper was influenced by my long held belief that the fundamental virtues of Plato and Gandhi, namely, justice and ahimsa, respectively, are necessary for a democratic culture or nation – state as well as a virtuous life of an individual. At this stage of the paper, let us take ahimsa to mean non-harm and compassion. When I turn to Gandhi’s thought, I will expand and elaborate upon the term. Objective: Based upon the foregoing considerations and the theme of this conference, the objective of this paper is to examine and compare the fundamental virtues of Plato and Gandhi, namely, justice and ahimsa and to consider the need of these virtues within a democratic culture and/or nation state. Both Plato and ‘Gandhi were interested in moral character and they believed that character was formed by the development of certain virtues. Furthermore, they held that when a person has developed a virtue, he or she would be disposed to act in accord with that virtue. In addition, Plato and Gandhi each thought that his fundamental virtue was necessary for a harmonious society. Also, although Plato’s ideal polis1 was not a democratic state2 and his sense of justice was not what it is taken to be in a democracy, I will argue that a view of justice, as a virtue and a 1 2 Polis refers to a city state. However, Athens, at the time of Plato’s life, was deomocratic.. right, as well as Gandhi’s view of ahimsa are necessary for a democratic culture or society. Approach: In researching and writing about any philosophy or people, especially that of the ancient past, the approach or methodology must take due account of hermeneutical considerations, especially that of an episteme, i.e. body of knowledge.3 I take this body to include: whatever a given culture or society believes to be truth or fact, accepted myths4 as well as environmental and historical influences. In fact, the body of knowledge includes whatever could influence the values and beliefs of a people. Thus, we philosophers of today need to avoid the mistakes which a number of philosophers have made in the past. These mistakes include: applying our modern methods and logical tools of analysis to a philosophy before understanding the episteme; and/or either ignoring or not taking due account of aspects of an episteme which are germane to a subject under consideration.5 3 I believe that I first learned about the importance of an episteme from reading the works of the great Post Modern thinker, Michele Foucault. Granted, he was concerned with discourse and how knowledge is based on discourse, yet he did realize that when we are studying any philosophy, we need first to look through the lens of the body of knowledge of the people at the time and place of the writings before we apply our modern methodologies to that episteme.. 4 Joseph Fletcher was right that myth is part of the human veltanschauung, i.e., world view. He has written numerous books on myth. 5 A number of years ago, while I was attending Claremont Graduate School, more than one of the analytic professors did this. In fact, when studying Plato, this was particularly apparent. In addition to the Dialogues of Plato, we studied the works of Gregory Vlastos’ and looked at Plato through his lens. We ignored or diminished the importance of Plato’s accounts of intuition, rebirth, and myth in general. In so doing, we were engaging in reductionism which I have come to see as a “great enemy” of reason. 1 Focusing again on justice as described in The Dialogues of Plato, let us determine what Plato meant by “justice.” In order to do this, we will examine his metaphysics as well as his views on the tripartite soul and an ideal state. His metaphysics includes: the Forms; the Good; and particular myths, which he describes, having to do with rebirth and the eternality of the soul. So, incorporating the hermeneutical approach, as stated, I will examine what Plato says about these subjects and based on the findings, state what I take justice to be for him. What will emerge from this study is a view according to which Plato believed that the universe was ordered and that order was necessary to establish harmony. Also, he thought that both the state and the individual’s soul or character should be ordered. Both kinds of ordering are undertaken to achieve harmony. Also, although the thrust of the Republic seems to be political, in that the state seems prior to the individual, we need not be concerned because the ancient Greeks believed that the individual was part of the state. In fact, they were viewed as one.6 Thus, we need not fall into an epistemic mistake of thinking of the state and the individual as separate. As we shall see, harmony in the state and the individual require justice. What we will learn, however, is that Plato’s sense of justice is not that which we in the modern world hold. It has more to do with ordering than fairness as we conceive of it today. After examining what Plato’s sense of justice is in the individual and the state, I will turn to the thought and practice of Mahatma Gandhi, Being a Gandhi scholar,7 I am 6 Christopher Vasillopulos, my colleague, has helped me to internalize this fact. I have written numerous articles on Gandhi (Please see references.), and lectured about his thought and practice in several cities in India (even at the Institute where Gandhi was shot) and in the United States. I also studied his beliefs and practices at the Gandhi Institute for Peace which is run by the Graduate School of Gandhian studies in Chandigarh, India. In addition, I have returned to the work on my book. Ahimsa: a Way of Life; a Path to Peace, which was interrupted by my husband’s ill health before his death last year. The publisher, Linus Publishers, with whom I had a contract, seems to be open to publishing the work when I have completed the manuscript. 7 2 very familiar with his fundamental virtue, namely, ahimsa. Actually, the term ahimsa, which originally meant non-harm, non-injury and nonviolence, later came to mean both non-harm and compassion. As we shall see, for Gandhi, these two virtues of non-harm and compassion were broad in meaning and scope. One cannot appreciate Gandhi’s thought or action unless she or he understands the profound influence that ahimsa had upon his life. I would go so far as to say that ahimsa was fundamental to all of his actions. In making this point clear, I will adumbrate the origin of ahimsa in the ancient Vedic literature and its development in Hinduism, Jainism and Buddhism. Then, I will show how Gandhi’s own thoughts about ahimsa were influenced by the three great Vedic traditions and a few persons and beliefs which also influenced him. Finally, I will show how he introduced ahimsa into the social/political arena by making it the foundation of his Truth or Soul Force against oppression. With this movement, he was able to end much of the oppression of the Indian population in South Africa and ultimately to free India from Great Britain’s colonial rule. In comparing Gandhi’s fundamental virtue of ahimsa to Plato’s views of justice, I will be emphasizing their shared beliefs that virtues are basically dispositions to act and that the more one has developed a virtue, the more she or he is disposed to act upon that virtue. Also, I will be looking at Gandhi’s view of a harmonious society and how we can counteract conflict and violence with ahimsa. Finally, even though Plato believed that democracy was a flawed system of government, I will argue that both justice, as a virtue and a right, and ahimsa are needed for a democratic culture or nation - state. 3 PLATO: Metaphysics: As stated earlier, in order to understand what Plato meant by “justice”, we need to examine his metaphysics and what he said about the tripartite soul and ideal state. To this end, let us begin with his metaphysics. The Forms: Plato’s metaphysics involves a realm that is transcendent to the world, namely, a realm of Being. Plato speaks of or alludes to this realm as one of Forms [Eidos]. Although he uses many words to describe the Forms, basically, they seem to be eternal, unchanging, non-material, verities that can be divided into at least three categories, namely: principles or standards,8 such as justice and beauty; eternal truths;9 and patterns.10 Also, he speaks of things in the world having reality because they partake of the Forms.11 Apparently things in the world receive their being or existence from the Forms, and a system of Forms. Thus, the Forms would seem to be causal. However, in the Theaetetus, a later Dialogue in which Socrates is not the main speaker and guide of the dialogue, Plato has the main character, Theaetetus, involved in seriously questioning 8 9 10 11 Phaedo, pp. 75-75; Meno, 82c, p. 365. Parmenides, 132d;; Timaeus, 49; Phaed, 76e Parmenides 75, 76, 129 and 132d. 4 what knowledge is. Since we know the Forms by knowledge, the Forms would also be in question. Apropos of Plato questioning what knowledge is, which would put into question what he says about the Forms, the authors of one of the translations of The Dialogues suggest that this questioning is in keeping with Plato’s thought because he always questioned himself. 12 I am not convinced of this suggestion. For one thing, Plato’s view that the Forms [somehow] cause things in the world seems to clash with his views of rebirth of the soul and immortality. How can a Form cause a human being to be, if her or his soul or character is eternal and subject to rebirth? The only answer would be to draw a sharp distinction between the soul and body, as Descartes did later between mind and body. The soul, in this case, would be altogether different from the material self. However, this raises the problem with the tripartite soul which I will discuss shortly. Whatever final view that Plato came to hold about the Forms, in general, I do believe that he continued to hold that there was some ordering principle in the universe which he called the “Good” and which he did associate with what he viewed as the supreme Form. Let us consider what he said about the Good. The Good: The Form of the Good: One view of the Good is that of the supreme Form.13 Perhaps, it would be better call this a “Form of Forms”. For, as it is described in the Parmenides, it would seem to be that which gives order to the other Forms, the system of the Forms, and indeed to the 12 13 Parmenides, p. 920. Robert Brumbaugh, p. 155 5 universe or scheme of things entire.14 Another possible view of the Good which is found in the Timaeus, is the myth of a personal deity [demiurgus] or an imaginative personification of the good which created the world or was its cause. Thus, it is not clear exactly what the nature of the Good is. However, A. E. Taylor, speaking about this subject, says that for the Greeks, there was not the sharp distinction between the personal and the impersonal. 15 Even so, given Plato’s many references regarding ordering and the importance of ordering needed to establish and/or maintain harmony, I think that whatever else it may be, the Good, for Plato, is an ordering principle or law. As such, I take it to be the supreme Form of the good. Furthermore, this Good, i.e., this ordering is what he seems to believe gives harmony to the universe. Although the Theory of the Forms itself is a myth, I tend to think of it as a speculation rather than pure fiction. As I suggested earlier, I think that Plato observed order in the universe and he gave an explanation of it based upon the episteme of his time. Based on that order, he thought that human life and the state should be ordered and wrote theories to explain that ordering. Even the tripartite soul can be considered myth, but I think that this is also a speculative attempt to explain an ordering whereby harmony can be achieved. However, in these speculations, Plato appealed to several myths which were ancient even in his time. Based upon what I have said about myth, let us turn to a consideration of its role in metaphysics. Metaphysics and Myth: 14 15 Greater Hippias, 297b. A. E. Taylor, p. 143 6 As most philosophers know, metaphysics is steeped in myth. Let us take “myth” in the broad and positive sense of: a sacred story of a people, the social purpose of which is to explain and support their most fundamental values and beliefs. As we know myth can and usually does involve fiction, and also speculation. However, as Joseph Fletcher realized in his vast work on myth, it is pervasive in human understanding. In myth there may also be truth or what is taken to be so, especially involving the history and culture of a people. Nonetheless, since the time of the empiricists, especially David Hume,16, many of our modern or recent philosophers have either ignored or diminished the myth embedded in the writings of the rationalists, including Plato.17 This is an epistemic mistake. Myth played an important role in the philosophy of Plato and furthermore, as stated earlier, some of what we would call “myth” in his writings was what I take to be speculation rather than sheer fancy. I take a number of myths that Plato puts forth in this light. Let us look then at what we gather about a weltanschuung or world view which Plato seems to have held or at least entertained.18 To that end, let us first consider what he had to say about the myth of immortality and pre-existence. Here I quote a passage from A. E. Taylor on the subject.19 Myths of Immortality and Pre Existence: I wrote my Master’s Critique on David Hume. Not only would he dismiss myth as an explanation of human experience, he held that all metaphysics and religion was meaningless! 17 As mentioned earlier, in the Philosophy Department at Claremont Graduate University, I was asked to ignore what Plato said about intuition, myth, etc. I was also told that analytic philosophers were interested in the “plumbing”, i.e., the enthymemes (logical arguments with suppressed premises) and how to correct them. 18 Ernest Becker, What Plato Said, p.136, In this book, one gathers that Plato never abandoned the belief that he had found the way of life and [I take it.] a world view which he taught to his students.. However, he did seem to entertain some views and then either discard them, or leave a question open as to whether or not he held these same views. 19 A. E. Taylor, p. 90. 16 7 In the great myths of the Gorgias, Republic, Phaedo, Phaedrus, and the half-mythical cosmology of the Timeaus, the convictions as to immortality and preexistence are made the basis for an imaginative picture of fortunes and destiny of the soul, in which the details are borrowed partly from Pythagorean astronomy, partly from Pythagorean and Orphic religious mythology, the main purpose of the whole being to impress the imagination with a sense of the eternal significance of right moral choice. The as yet unembodied soul is pictured in the Phaedrus under the figure of a charioteer borne on a car [chariot] drawn by two winged steeds (spirit and appetite), in the train of a great procession of gods whose goal, as they move round the vault of heaven is that ‘place above the heavens’ where the eternal bodiless Ideas [Forms] may be contemplated in all their purity. The soul which fails to control its coursers sinks to earth, ‘loses its wings’ and becomes incarnate in a mortal body, forgetting the ‘imperial place whence it came.’ Its recollections may, however, be awakened by the influence of beauty. [Kalos refers to both beauty and good.], the only ‘Idea’ [Form] which is capable of presentation through the medium of the senses. Love of beauty rightly cultivated develops the love of wisdom and of all high and sacred things; the ‘wings’ of the soul thus begin to sprout once more. After one early life is over, there follows a period of retribution for the good and evil deeds done in the body, and, when that is ordered, the choice of a second bodily life. The soul which has thrice in succession chosen the worthiest life, that of a lover of wisdom is thereafter dismissed to live unencumbered by the body in spiritual converse with heavenly things. For others, a pilgrimage of ten thousand years’ retribution after each life is necessary before the soul can become fully ‘winged’ and return to her first station in the heavens.20 In the Republic, Plato relates from the mouth of a witness from the world of the dead what happens at the time of incarnation. Destiny here is key, as it was and is in Hinduism. Also, as in Hinduism, virtues depend not on fate, but on the character of the soul. A. E. Taylor expresses this view: 20 Taylor, pp. 90 – 91. 8 According to the tastes and dispositions of the individual souls, and to the degree of wisdom derived from philosophy or from experience, they make their choice, and this once made is irrevocable.21 Based upon A. E. Taylor’s description of Plato’s accounts of rebirth and the eternality of the soul, let us turn now to an examination of what Plato says about the tripartite soul. The Tripartite Soul: Of the numerous questions and problems associated with Plato’s Dialogues, I agree, at least in part, with one of the twentieth century Plato scholars, W.K.C. Guthrie.22 In his discussion of the problem, he quoted and expressed his agreement with R. Hackforth who was another Plato scholar of the same period. The quote was: “The problem of the tripartite soul is the thorniest of all Platonic problems and in spite of the vast amount of discussion in recent years, it cannot be said to be solved.”23 I would say that this is one of the “thorniest” of Platonic problems. However, I believe that if we are careful to consider the pertinent aspects of Plato’s episteme, we can make sense of the tripartite soul and its relation to the city-state. First, we must agree with a number of scholars who have made clear that the accounts of the soul in the Gorgias, Republic, Meno, and Timeaus are not the same. In 21 Taylor, p. 95. W. K. C. Guthrie, “Plato’s Views on the Nature of the Soul” in Plato: a Collection of Cricial Essays, Gredgory Vlastos, Anchor Cooks, Doubleday and Company, inc., New York, 1971 23 R. Hackforth, Plato’s Pahedrus, 1952, p. 76 as quoted in 22 9 the Republic, we have the view of the tripartite soul. A.E. Taylor gives a good account of the three parts.24 According to him, the parts are: The reasoned part: the part with which we reason, the calculative or rational part. The appetitive part: the part with which we feel the appetitive cravings connected with the satisfaction of our organic bodily needs. The spirited part: the part made up of the higher and nobler emotions, chief among which Plato reckons the emotions of righteous indignation. The three parts form a unified soul, although Plato made clear that reason must be in control of the other two parts. In the Republic, Plato argues that the soul is eternal. However, in the Timaeus, we read that only the reasoned part of the soul is eternal.25 This view is in keeping with what Socrates said about virtue. He held that knowledge alone is virtue. The problem with such a view is that there are other parts to the human soul or character and if the soul must be virtuous in order to achieve an eternal state in the realm of Being, then such a state is impossible. Surely, Plato must have considered this problem. However, in the Meno he may have been focusing on purification. If the soul must be purified in order to “see” into reality, and eventually to gain release from the cycles of rebirth and to achieve a permanent state of life in the realm of Forms,26 then how can the parts that are tied to the body and cannot be purified, be eternal? Or put another way, how could a human being ever achieve the virtuous state needed for immortality? This is a quandary. However, in the Phaedrus, Plato had implied that purification takes place in the repeated 24 25 26 Taylor, The Mind of Plato, p. 80. Paul Shorey, What Plato Said, p. 287. The “seeing” is obviously an intuitive grasp which only those who have the Love of Wisdom have. 10 cycles of rebirth including the time when a soul is disembodied and can chose what kind of life to pursue in the next life-time. Whatever Plato came to hold about this matter, I think that the tripartite state of the soul is psychologically correct as it makes sense of our individual experiences related to both the appetites and the spirited parts of ourselves which he called “soul” and we call “character.” It would not be an adequate account of character to just emphasize the intellectual aspect of our natures, as Socrates did. One scholar suggested,that the tripartite soul may have been Plato’s attempt to overcome the problems with Socrates’ view.27 Granted, the foregoing accounts of rebirth and immortality of the soul are myths and, as stated, they involve fiction. However, it is interesting to me that the ‘myth’ of rebirth has existed in India for thousands of years. It is fundamental to Hinduism, Jainism, and to some extent Buddhism.28 I view this more as a speculative world view or scheme of things entire than simply fiction. As Kant made clear, such views are beyond what can be proven, but so are the views of the monotheistic religions that speculate about an after life in a heavenly state. What I find interesting is that some of the early Western Christians, who wrote about Plato and the Hindus, emphasized the myth of rebirth as fiction. Yet, they did not view their own myth of creation and salvation as fiction. In contrast to a Christian or religious lens, some of the more recent philosophers who write about Plato either ignore or diminish the myths. I believe that this is an epistemic mistake. Taylor, “The Soul of Man” in The Mind of Plato. The great Buddhist scholar, David Kalapuhana, Professor Emeritus from the University of Hawaii, held that Siddartha Gautama, the Buddha did not believe in rebirth per se. He was not interested in metaphysics and said so. However, his audience were Hindus who all believed in rebirth, so he spoke in those terms. What he seems to have held is that the wheel of life may take place during one’s life time rather than in life cycles. I did an NEH Summer Institute at the University of Hawaii some years back and David Kalapuhana was the Director. Also, I have read a number of his books on Buddhism. 27 28 11 The Ideal State: Plato’s ordering of the state, as we shall see, was based on guardian rulers who were just in their actions. Plato did not see that kind of justice in the democratic system of Athens which had taken the life of Socrates. So he wanted rulers who could be counted on to act justly. So he wrote his view of an ideal state. In his ideal state, people had different roles. Some were to be rulers and some soldiers, both of which he called “guardians,”29 and some were merchants and skilled workers. He reasoned, as did the ancient thinkers of India, that the city-state would be more ordered and hence harmonious, if each class of person were to become expert at her or his work. Thus, his ideal city-state would be what we would call “closed.” It was not democratic, as the people were ruled by an elite group of intellectuals who ruled because they could, not for gain or fame. What is significant about Plato’s ideal state, is that the guardian rulers had to be just in order to form and exact just laws that would establish and maintain order and thus harmony for the people of the state. That is why I think Plato was so keen to argue for the ordering and thus harmony of the soul. Let us turn now to a discussion of justice and the soul. Justice: Justice and the Soul: For Plato, a just person was virtuous because his or her soul was in harmony, i.e., reason was in charge of the appetites and spirited part of the soul. Thus, this person could be expected to act in a just way. This is a difficult claim to substantiate because most 29 Barker, p. 198, Later, he called the soldiers auxiliaries. 12 people would argue that even if one were to know, via reason, what was just, this would not ensure that the person would always act in a just way. In order to strengthen this claim, I think that Plato’s myths about rebirth and purification of a soul that enable it to live eternally in the realm of being, are required. Given these myths, let us take a very close look at Plato’s view of the soul and justice. Plato makes very clear that the reasoned soul or the soul that is devoted to wisdom is a soul that is ordered. Reason is in control of the appetites and the spirited part of the soul. If the soul is ordered, it is in a state of harmony. Such being the case, and given the belief in a soul’s rebirth and gradual purification, a soul that is in harmony and focused on what he called “the love of wisdom”, cannot help but be just. The persons with such a soul are those whom Plato believes should be the leaders that are chosen to rule the state. Because souls are reborn, they must learn about the physical world, so they must be educated. Education of the rulers is based on the recognition of possible rulers. This takes place with young boys and girls. The chosen children are reared and educated by the state. The education is lengthy, but various tests are given which eliminate those students who do not excel. Thus, the students will either prove themselves worthy of being rulers or fail to do so. Of course, given the view of purification of the soul, those who have the love of wisdom will excel at their studies and become guardian rulers or philosopher kings. Let us turn now to the explanation of how Plato’s ideal state would be governed Justice and the State: 13 Justice is the virtue that is needed for the guardian rulers of the state and thus, those rulers must be counted on to act with justice. Also, even though they will have a long education in how to become rulers, it is their souls, or as we would say, their character, which will determine how they act. Hence, Plato’s analysis of the soul is such that, according to him, it must, as the state, be ordered so that it is in harmony. If it is, he argues, the person will be just to others. Plato’s seems to strengthen the foregoing belief when he compares the parts of the soul with the classes of persons in the state.30 A. E. Taylor and Paul Shorey suggest that what Plato meant by “justice”, as applied to the state, was that each part of the society was concerned with its own duties and developing its crafts [techne].31 Apparently, he meant the same for the soul. Those who, by nature and or training are wise should be the ruling guardians of the state while those who by nature respond to the appetites and/or their spirited natures, will have to abide by the law of the guardian rulers. These persons will have to learn temperance and moderation. They include the merchants and the skilled workers. However, even the soldier guardians, who have courage as a basic virtue, must obey the dictates of the ruling elite. Justice and the Good: Focusing on the tripartite view of the soul, again, what we see is that the Good is an ordering principle not only of the universe, but of human beings and the state. In these latter two domains, it has to do with justice as the highest virtue. Based upon what has 30 31 A. E. Taylor, p. 83. A. E. Taylor, p. 104; and Paul Shorey, “The Republic”. 14 been said about justice and the Good, only the elite rulers could have a soul that is in harmony, because only they are ruled by wisdom. Furthermore, if we accept the myth of rebirth, many of these rulers are so “spiritually” advanced that they will always act justly. Conclusion: Based on both Plato’s writings and a number of scholars offering interpretations of what Plato said, it seems to me that ”justice” for Plato was basically a kind of ordering, namely doing what one does well based on what kind of character and mind she or he has and not being concerned with doing what others do.32 Given this view, I would like to tweak out a bit of our sense of justice as fairness, but the closest I can come is to say that if each person did what she or he was disposed to do by nature and/or education, there might be a kind of fairness and indeed a harmony within and between the classes. However, there is no sense of democracy in which the people are sovereign. Far from it! Also, there could be no possibility of the lower classes aspiring to the level of rulers. In fact, I believe that Plato’s ideal state looks quite similar to the Hindu in that one is basically “stuck” with her or his station in life and has to be reborn into higher levels of society. This is especially true, if we take seriously the myth of rebirth. Having examined Plato’s sense of justice, I want to turn to Gandhi’s notion of ahimsa, However, before I do so, I want to mention some of the shared beliefs and values of the ancient Greeks and the ancient Hindus which influenced the thought of Plato and Gandhi respectively. Some Similar Metaphysical Views of the Ancient Greeks and the Ancient Hindus: 32 Ibid. 15 The ancient Greek philosophic traditions, which influenced Plato’s thought, and the ancient Hindu philosophic traditions, which influenced Gandhi’s thought, had some general beliefs and values in common. Among the general beliefs, was that there is a realm of becoming, involving change, and a realm of being involving permanence. Also, the Hindu tradition and the Greek tradition held that the permanent realm was more real than the changing realm which was the physical world. Interestingly, Gandhi did not share these beliefs about the world, as he took the world to be real.33 In addition to these ontological beliefs, both of the ancient traditions held a notion of the soul which was separate from a body, although embodied when in the physical world. The soul was eternal; subject to rebirth in different bodies; and after a kind of purification for the Greeks, and an overcoming of the ego and achieving self-realization, for the Hindus, a soul could eternally reside in the state of Being.34 The difference between the two traditions is that for the Hindu, there was no personality or even personhood involved at the final state of the soul when it was released from the constant cycles of rebirth (samsaras). Values which the ancient Greeks and ancient Hindus held in common basically had to do with a moral or virtuous character. Furthermore, the virtues which formed character had to be taught and developed. Both traditions held that courage was a virtue. For the Greeks, it was particularly important for the soldiers to develop. For the Hindus, ahimsa was the major virtue, but, as with the Greeks, courage was important for the warriors or soldiers. For Gandhi, each individual had to develop courage in order to live an engaged life according to his beliefs, which we will discuss, but especially the 33 34 Gandhi, Truth is God, p. 11. Aristotle did not share this belief. 16 satyagrahis, i.e., members of Gandhi’s truth force against oppression, had to have courage. Otherwise, how could they engage in acts of non-cooperation and acts of civil disobedience with no weapons and a determination not to harm anyone? Other virtues differed in the two traditions. The cardinal Greek virtues were wisdom and justice, which the guardian rulers had to have; courage, which, as stated, the guardian soldiers had to have; and temperance or moderation which the merchants and skilled workers had to have. For the Hindus, as stated above, ahimsa was the main virtue, but courage was important, especially for the warriors, because they fought battles throughout history. These major differences, I believe, may have been because of the fact that the Greeks were much more focused on the citizens within a state and the governing of those citizens by the state, while the Hindus (as well as the Jains and Buddhists) were more focused on an individual and how that individual develops a virtuous character. Despite the different virtues, both traditions held that moral character is formed by virtues and that virtues within a human were dispositions to act that had to be taught and practiced and the more one had developed a virtue, the more likely he or she was to act upon it. Plato, as we have seen, also believed that some virtues, such as justice and beauty, were eternal Forms. Even though the Hindus did not believe this, they did share with the Greeks the view that persons at various stages of spiritual development, i.e., the development of the soul, would be more or less virtuous. With regard to status and classes, both traditions held that the more virtuous one was, the higher status one should have in the social arena. Also, it should be the virtuous 17 persons who either lead the state [especially Plato’s view of the guardians] or influence the thought of the people and are revered by them [the Hindu Brahmans of priests]. Gandhi’s Metaphysics: Given what was said above about the shared beliefs and values of the ancient Greeks and ancient Hindus, let me briefly explain the metaphysical view which Gandhi held. As stated earlier, he was a Hindu, and more specifically, he belonged to a particular sect that is pervasive in India today. It is called Advaita Vedanta. Advaita means nondual and Vedanta means unified. Hence, this is a monistic view of reality. In such a view, the world is devalued, i.e., it is not as real as the transcendent level of Being. As we know, Plato shared this view. Gandhi, however, did not accept this view completely, as he argued that although he was an Advaitin, he thought the world was real.35 He did accept what all Hindus and Jains and many Buddhists believe and that is rebirth. In fact, with each of these traditions, it is the Karmic Law which in conjunction with one’s duty [dharma], based on one’s class or caste, brings about one’s destiny. Other basic themes in Hinduism include the yoga paths of: devotion (bhakti), good works (karma) and a high level of spiritual intuition based on the development of both reasoning and virtues (jnana). Each of these yoga paths involves meditation which I have discussed in another paper.36Another belief is the stages of life which include: student, householder, forest dweller (when one decides to take on a more contemplative/ spiritual way of life) and a holy state wherein one has renounced the worldly life This statement is found in a little book, with Gandhi’s sayings, called Truth is God, by Prabhu, pp. 10 – 11. 36 . Hope Fitz, a booklet, Ahimsa: a Way of Life: a Path to Peace” published by the Gandhi Lecture Series and Vedic Studies at the University of Massachusetts, Dartmouth, 2007. 35 18 (sannyasin). Still another belief is in the four varnas, i.e., classes or castes that many Hindus still accept. The basic varnas are: the brahmans or priests; the ksatriyas or warriors, the vaisyas or merchants and skilled workers and the sudras or servants. In addition, there was the Harijan or outcastes. As far as I know, Gandhi never rejected a belief in the varnas or the belief that one had to spend many lifetimes in a varna before he or she could ascend to the next higher varna. However, Gandhi did spend a great deal of time and effort working in behalf of the Harijans. There is much more that can be said about Gandhi’s metaphysics and his development of ahimsa, but I think enough has been said that we can see some similarities and differences in the fundamental virtues of Plato and Gandhi. Having noted Gandhi’s metaphysics, let us turn now to a consideration of Gandhi’s fundamental value of ahimsa. Unlike Plato, Gandhi was not a trained philosopher. Also, because ahimsa was a way of life for him, it is necessary to at least sketch aspects of the development of his character which, as we shall see, involved ahimsa. Gandhi and Ahimsa: Gandhi’s Life: Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi (October 2, 1869 – January 30, 1948) was born in a seaside town in Gujarat, India. His family, although of the Vaisya or merchant class,37 were well to do as his father was a successful merchant. There was not much about Mohandas Gandhi’s childhood to indicate his future greatness. The one characteristic 37 As is well known, India has had and still has, especially in the rural areas, a class or caste system. The four major classes are: Brahmin or Priest , Ksatriya or Warrior, Vaisya or Merchan and Sudra or Servant. 19 that stood out was his moral sensitivity. This did not mean that he was always what we call a “good boy”. As many young boys have done, he struggled against his “tethers” and rebelled at times. His acts of rebellion included smoking and eating meat, which was against his religion. However, as he grew and developed, he became more and more sensitive to any pain or grief which he caused his father, Karamchand, mother, Putlibhai, or others. Gandhi’s parents had a decided influence upon his developing moral character. His father was a gentle man. Once, when Gandhi admitted to some act of rebellion, his father did not scold him. However, when Gandhi saw a tear trickling down his father’s cheek, he felt a deep sense of shame. Years later, shame was to become central to Gandhi’s nonviolent force against oppression, satyagraha, which we will discuss shortly. Perhaps the greatest moral influence on Gandhi, as a child, was his mother. The family was Hindu, but the father and mother had made the acquaintance of a Jain priest in their neighborhood. He visited their house, and apparently Gandhi’s mother was very influenced by the Jain thought and practices which he taught her and she, in turn, taught to Gandhi. These included, fasting, meditation every day, following a strict vegetarian diet, and taking a vow to not hurt or harm anything deliberately. Such practices are present in the Hindu tradition, but they are not as strictly adhered to as in the Jain tradition. Gandhi was married at thirteen years of age. His wife, Kasturbai, was also thirteen. Even though we today are shocked at this child marriage, at the time it was not unusual for Hindu families to arrange such marriages. Also, the young couples traditionally lived with the groom’s family, so they were not in need of an income. Even 20 though Gandhi and Kasturbai had a lasting marriage and they loved each other deeply, Gandhi later wrote protesting against child marriages in general. Kasturbai had a steadying effect on Gandhi’s life. When they were young, he said that he was jealous of her and tried to dominate her. She helped him to overcome these forms of himsa. During their years together, she “kept the home fires burning”, while Gandhi was involved in social/political activities and in his writings. She reared their sons and took part in most of his endeavors. In time, she even spoke for him when he was put in jail, as he was often in South Africa and in India. Returning to the subject of Gandhi’s youth, his father suffered a long illness and when Gandhi was about the age to attend college, his father died. The family wondered how they were going to afford the cost of Gandhi’s college education. In those days, merchant people, of means, as well as the higher classes, often sent their sons to colleges in England. So, after Gandhi’s older brother secured the money for Gandhi’s education, he was sent to a law school in London. His mother’s last words to her son were to the effect that he was to avoid women, alcohol and meat. He abided by his mother’s wishes, but it was difficult to avoid meat, especially learning how to prepare vegetarian food or to find a vegetarian restaurant. In a few years, Gandhi graduated from law school and obtained his law degree. However, in part due to his shyness, he was not able to conduct his first case, and he showed no promise for his chosen profession. It took the time in South Africa, where he was sent to defend the Indian people from the oppression of the English courts, for him to come into his own and become a great lawyer and leader of his people. I have long believed that the “match that lit the fire” of the shy young lad so that he became one of 21 the bravest men who have ever lived, if not the bravest, was the night that he was thrown off the train in Maritz Burg, South Africa on his way to Transvaal. He had purchased his first class ticket by mail, but when the conductor realized that there was a man of color in a first class compartment, Gandhi was told that he would have to go to the third class compartment. He refused and he and his luggage were literally thrown off the train. It was this incident, I believe, that aroused his indignation at the injustice of this act and began a “fire” within him so that he would fight against such oppression. But, as we shall see, that “fight” was, for him, always nonviolent. After arriving in Transvaal, he met with the Indian leaders of the community. What he learned about the oppression of the Indian people inspired him to challenge the unjust laws which denied the Indians equal status in Transvaal. Some of the laws which were enacted before and during Gandhi’s struggle for Indian rights in South Africa had to do with: showing an identification card wherever one went in order to travel and secure work; not being allowed to own property, having non-Christian marriages declared illegal; and police being allowed to enter an Indian’s home unannounced and uninvited. It was in South Africa that Gandhi developed satyagraha. Satya means Truth and graha means to grasp firmly. So satyagraha, a Sanskrit term, refers to a Truth Force or Soul Force against oppression. Oppression for him involved a corrupt government and/or corrupt government officials. However, with his nonviolent truth force he was able to change the oppressive laws against the Indians in South Africa and after he returned home to India, he used this force to unite the people in their struggle to free themselves from English rule. They did so. 22 Ahimsa in Hinduism, Jainism and Buddhism: Slowly, Gandhi came to understand ahimsa as a way of life. But to understand what this meant for him, we need to examine this ancient concept and how it developed. The origin of ahimsa is about 3,600 years old. We find the rudiments of it in the Vedas, which are the sacred writings of the Hindus. To be more precise, it is in the Yajur Veda, the third of the four great books of the Vedas. Throughout that text, there are a number of references, to justice, how members of a family should show kindness to one another, being concerned for a community, harboring no hatred towards anyone, and most importantly, not harming others.38 In the Upanishads, which are the ending sections of each of the Vedic books, this idea of ahimsa was expanded. It even concerned animals. One was not to harm an animal unless that animal had threatened him. However, there were exceptions to violence that had to do with when it was morally acceptable to kill. The Hindus believed that it was all right to kill a human in certain cases, such as to protect the king. Also, certain animals were killed, and still are, in various sacrificial ceremonies. Jains and Buddhists, in contrast to the Hindus, do not condone killing of any sort. Jains, especially, are absolutely committed to non-harm, non-injury and a vow not to hurt any human or animal. Also, the Jains do not want to hurt any plant unnecessarily. This seemingly extreme sense of non-harm is because the Jains believe that every living being has a soul and one is not to interfere with the purification of that soul in its cycles of rebirth. Even a living organism could, after many lifetimes, evolve to a level with a mind and then, if one abides by the rules for purification and does not intentionally harm any living being, he or she might achieve a state of omniscience that, strangely, sounds very 38 Yajur Veda, published by Motilal Banarsidass, Delhi, India. 23 similar to Aristotle’s explanation of the one supreme state of Being.39 So the Jains developed ahimsa to the highest level of non-harm, non-injury, and a vow not to hurt any living being by thought, word or deed. What impresses me about the Jains is not the very complex canonical law which is based on non-harm and a belief in purification of the soul, but the way that they live in this world today. I know a number of Jains in the United States and India, and they try to live by the major principles or vows of non-harm, truth, non-stealing, not being attached to material gain; and for mendicants a vow of celibacy (for lay people this would mean no sex outside of marriage).40 In addition to ahimsa as non-harm, the Jains also spoke of compassion (karuna in Sanskrit or anukampa in Prakrit). Yet it was non-harm which they focused upon. It took the Buddhists with their metaphysics to develop compassion [without ego] to the fullest. Siddartha Gautama, the Buddha, believed that all life was interconnected, interrelated, interdependent, co-arising and co-existing. Hence, according to this belief and another that we are both created and creating in this dynamic state of reality, he came to the conclusion that there was no God, no soul or self and no abiding state of reality.41 The belief in a soul or ego, he held is a construct. Also, the world is real, but it is in a constant state of change. With such a belief system and no “tight boundaries” of the self, compassion is easier to develop as one is not focused on a self or ego. When compassion 39 The Jains think of this omniscient state as one in which the soul, which is free from worldly suffering, can engage in reflection and contemplation. It is no longer involved in wordly affairs. 40 I am not a Jain, but I am a Jain activist because they practice non-harm in all aspects of their lives. Because I want to promote non-harm, I am a member of the Academic Council for Jain Studies in North America. 41 In Pali, this theory is call patticia samuppada which means dependent origination. 24 is developed, as Buddha expresses it in the Abidharma ,”Compassion embraces all sorrow or stricken beings and eliminates cruelty.42 Having only adumbrated the development of ahimsa in the three great Indic traditions which profoundly affected Gandhi’s beliefs and practices, let me briefly mention a few persons, besides his parents, who influenced his thought about ahimsa. One of these persons was a Jain monk whom Gandhi met and admired. They did not see one another often, but they did correspond. This monk’s name was Shri Rajchandrabhai. He deepened Gandhi’s understanding of the Jain beliefs, that I have related, and those which Gandhi’s mother, Putlibhai, had taught him when he was a child. In fact, Shri Rajchandrabhai was one of the persons who had the greatest effect upon Gandhi’s early thought.43.A second person who influenced Gandhi’s thought about ahimsa was the famous Russian writer Tolstoy. Gandhi even named one of his ahsrams (a community, often a religious or spiritual community) after Tolstoy. The big difference between the two men regarding ahimsa, was that Tolstoy was a pacifist and Gandhi was not. Gandhi said a number of times that he abhorred violence, but he preferred it to cowardice. Gandhi condoned violence in the case of defense: of oneself, one’s loved one’s, one’s community, state, and even in rare cases, one’s nation.44 However, I have come to believe that, in general, he would not condone violence in a protest of satyagraha, i.e., Gandhi’s truth force against oppression, because, as we shall see, a satyagrahi, i.e, a follower of Gandhi’s truth force against oppression, must never resort to violence and be willing to sacrifice his or her own life in order to convert the oppressor to ahimsa 42 43 44 Ghosh, Abidharma, as quoted in Ahimsa: Buddhist and Gandhian, p. 27. Digish Mehta, Shrimad Rajchandara, p. 82. Raghavan Iyer, p. 203. 25 Focusing again on influences to Gandhi’s thought and practice of ahimsa, two of the many beliefs which influenced Gandhi were from Christian sources. One was the Sermon on the Mount in the Bible. Gandhi was especially taken with the idea of turning the other cheek. Another source was from the Quakers or Friends. Gandhi learned about them from Tolstoy and he was very impressed with their non-violent but socially and politically active way of life. Having just touched upon the major influences of Gandhi’s view of ahimsa, let me now discuss what ahimsa meant to him and how he practiced it in every aspect of his life. In 1916, Gandhi set forth what he meant by ahimsa. He held that there was a negative and positive side to it. The negative side was: no harm to any living being by thought, word or deed and a vow not to hurt. The positive side was: the greatest love (compassion) for all creatures.45 However, it is important to recall that Gandhi, as the Greeks, held that courage was a virtue and for him each person had to develop courage before he practiced ahimsa and especially those satyagrahis or “warriors” who would fight oppression with only the tools of non-harm and compassion. As to the uses of ahimsa, these include: a means to Truth or God; standing up and speaking out for what is true or right; a fundamental virtue for living , and the foundation of Gandhi’s truth force against oppression. By “Truth,” Gandhi usually meant God, and he described God as love. Hence, by a hypothetical syllogism, one could say that Truth was love. As to a notion of God, Gandhi seems to have held two views. One view is of an impersonal absolute state of being that cannot be known, but can, after gaining selfrealization, which involves many life cycles, be experienced. When it is experienced, it Gandhi, “The Modern Review, as quoted in Raghavan Iyer, The Moral and Political Thought of Mahatma Gandhi, pp. 178 – 184. 45 26 is described as saccidananda which translates to truth or being, consciousness (Gandhi spoke of knowledge rather than consciousness) and a state of spiritual bliss.46 Another view of God which Gandhi held was that of a personal deity. As I wrote in an earlier paper about him, he never resolved this discrepancy. 47 As to the meaning of truth, Gandhi did not mean just not falsifying information or deceiving, he meant having the courage to stand up and speak out for what is true or right. Regarding ahimsa in one’s everyday life, one is to practice non-harm and express compassion whenever and wherever possible. Also, these virtues are not just restricted to humans, but to all life. This is no easy feat, but Gandhi tried to live it every day of his life. Finally, the greatest challenge is satyagraha. Such is the case, because a satyagrahi must go into “battle” with only the weapons of non-harm and compassion. What is being fought is oppression by people or institutions. Furthermore, one must not harbor anger, let alone hatred, towards one’s adversary. In fact, recalling what was said earlier about shame, Gandhi believed that if we used ahimsa and never gave in to violence, then the oppressor(s) would feel shame and then there was a possibility that they could be converted to ahimsa as a way of life. This is why in an act of satyagraha, one should not resort to violence even in defense. When the satyagrahis were being beaten by the English soldiers at the march on the salt mines, they did not strike back because it was important that they did not use violence in their protest. When Gandhi first developed satyagraha, in South Africa, he thought that noncooperation was a duty of a satyagrahi when fighting some form of oppression. He 46 sat is the stem of the noun satya which means truth, existence of Being; cit is the stem of the noun citta which means mind stuff, and ananda is a noun meaning a kind of spiritual state in which one is fully aware of the scheme of things entire and thus fulfilled. 47 Hope Fitz, “Gandhi’s Ethical/Religious Tradition/” 27 thought that civil disobedience was a right rather than a duty. [He learned about civil disobedience from David Thoreau.] Later, he changed his mind and came to hold that even civil disobedience could be a duty under certain circumstances. A Summary and Comparison of Gandhi’s and Plato’s Most Fundamental Values: Having explained Gandhi’s fundamental virtue of ahimsa, let us turn now to a summary of Plato’s notion of justice and Gandhi’s view of Ahimsa. Plato’s Justice: In reflection upon Plato’s view of justice, his was a view that justice was a kind of ordering that he thought would bring harmony to the state and the soul. Apparently, he observed what he took to be order in the universe which is composed of the Forms. Also, there is a Form of the Good, which I take to be an ordering principle, whatever else it is. Because Plato believed that order would bring about harmony, he thought that order should be applied to the state and the individual. With regard to the state, each person was to do what he or she did best and not try to do what other people did well. In his state, the guardian rulers would both create the laws and see that they were enacted. These rulers would have to be just so that order could be established and maintained and in order for them to be just, the souls of the rulers would have to be such that they would act with justice. The guardian soldiers would act with courage to protect the citizens, but they as well as the merchants and skilled workers would have to obey the guardian rulers. The merchants and skilled workers would have to develop temperance or moderation in their lives in order to do their work skillfully. Again, they had to obey the rulers. 28 In the soul, the reasoned part, or aspect, was to be in charge of both the appetites and the spirited part of an individual. Only in this way, would the individual be able to order his or her life and thus achieve harmony. Also, one’ station or place in the state was determined by the part of the soul that dominated his or her life. However, as with the classes in the state, it is clear that one’s soul and his or her station in life has more to do with one’s character than with one’s education or training. When one is spiritually developed or has reached a high level of the purification of the soul, this determines what class one belongs to. This development is because of the cycles of rebirth including when one is disembodied in the realm of the Forms. Gandhi’s Ahimsa: Gandhi’s ahimsa, as we have seen, is the culmination of an ancient idea that originated in the Hindu tradition and was developed by the Hindu, Jain and Buddhist traditions. Gandhi believed that ahimsa embodied both non-harm to and compassion for all life. He practiced it as a means to Truth as God and the fundamental virtue for life. One can see this in his account of the practice of law. He wrote: I had learnt the true practice of law. I had learnt to find the better side of human nature and to enter men’s hearts. I realized the true function of a lawyer was to unite parties riven asunder. The lesson was so indelibly burnt into me, that a large part of my time during the twenty years of my practice as a lawyer was occupied in bringing about private compromises of hundreds of cases. I lost nothing thereby – not even money, certainly not my soul”48 48 Mahatma Gandhi , The Law and the Lawyers, Chapter 12, p. 45, 1027. 29 Not only did Gandhi practice ahimsa as a way of life, he made it the basis of his satyagraha, i.e., his truth force or soul force against oppression. This was his contribution to the development of ahimsa. He had brought it into the social/political arena. Armed with ahimsa and courage, he was able to take on the government of Great Britain and to win rights for the Indian people in South Africa and the freedom of India from Great Britain’s colonial rule. Having summarized and compared the fundamental virtues of Plato and Gandhi, let us consider why both justice, as a right as well as a virtue, and ahimsa are necessary in a democratic culture or nation state. Justice and Ahimsa are Needed for a Democratic Culture or Nation State: Justice: As we have seen, Plato’s notion of justice as a virtue is basically an ordering of the soul that is necessary for the ordering of a state. Apparently Plato based his beliefs about ordering on his observation that there is a natural ordering of the universe and this ordering brings harmony. With regard to the ordering of the state, it was to be run by guardian rulers, and the citizens had to obey them. However, they had to be just, in the sense that they could keep order, or the state would not have been harmonious. Plato’s sense of justice, as an ordering of one’s soul or character and the state is not the sense of justice that is needed for a democracy. A democracy which is governed by the people is concerned with justice as fairness. Also, whereas justice is viewed as a right as well as a virtue that is part of one’s character, fairness is viewed more as a right. However, what constitutes fairness is not easy to determine. For one thing, there is the 30 issue of distributive justice. To make this clear, take an example of those of us who are United States citizens. We live in a capitalist society. Given this background, many of us would agree that initiative should be rewarded because it is deserved. However, at this time, many of the wealthy and privileged seem to think that they are the deserving of the great disparity between their income and that of the masses because they have “earned” it. Also the voices of the masses think that they are deserving of the “American dream” including a job, a home, vacations, and a decent retirement. So, again, what is fair is not easy to decide. Also, the more power that the people have, the more they demand fairness for themselves. Thinking internationally, other issues having to do with fairness are: natural and civil rights; constitutions which focus on either limited rights or needs of the people; the future of nation states and economic survival. Although determining what is fair is fraught with problems, it is obvious that justice as fairness is needed in a democratic culture or state, However, it is clear to me that Plato’s views about who and what the rulers need to be has validity today. To wit, I think that those in power, and in the U.S. those who represent the people, must be educated, highly intelligent, world traveled, and actually acting in behalf of the people. But above all, the rulers must be moral or live virtuously. What we observe all too often in our democracy is rulers striving for power and wealth. As to the people, they should not be elected to power unless they have the necessary knowledge and character to rule. Ahimsa: 31 It seems clear to me that ahimsa is needed in any culture or state as well as for individual well being. Aristotle’s notions of living virtuously, supported by his ideas of friendship and citizen involvement in government would work for a small community, but not in our large nation states. We need to have people determined not to harm one another, or other living beings, except for food or survival, and the earth itself, and to really care for one another. We are a family of human beings living in different cultures and nation states and as Buddha said, we are interconnected, interrelated, and interdependent. If we don’t solve the environmental problems of our earth, water and air and our social/political problems soon, our progeny and other life cannot be sustained on this planet. 32 REFERENCES Plato: Works by Plato: Plato: The Collected Dialogues, ed. by Edith Hamilton and Huntington Cairns, Bollington Series LXXT, Princeton University Press, c. 1961 _______, Plato’s Republic, tr. by G.M.A. Grube, Hackett Publishing Company, Indianapolis. c. 1974. _________, Plato’s Phaedo, tr. with an introduction and commentary by R. Hackforth, The Library of Liberal Arts, Bobbs Merrill Company, Inc. 1955/ Books about Plato’s Works: Barker, Ernest: Greek Political Theory: Plato and His Predecessors, Methuen & Co Ltd., London, first published 1918, reprinted 1961, 1964, and 1967. Brumbaugh, Robert S: The Philosophers of Greece Thomas Y. Crowell Company, New York, c. 1964. Cornford, Francis MacDonald, Plato and Parmenides, The Library of Liberal Arts, Bobbs Merrill Company, Inc. (No date give.) Shorey Paul: What Plato Said, abridged edition, Phoenix Books, The University of Chicago Press, Chicago, c. 1933, Reprinted 1965. 33 Solomon, Robert C. and Murphy, Mark C, What is Justice: Classic and Contemporary Readings, Oxford University Press, Oxford, England, c. 1960 Taylor, A.E.: The Mind of Plato, The University of Michigan Press, Third Printing, 1969. Articles about Plato: ________ Plato I, A Collection of Critical Essays: Metaphysics and Epistemology, ed. by Gregory Vlastos, Modern Studies in Philosophy, Amelie Oksenberg Rorty, General Editor, Anchor Books, Doubleday and Company Inc., New York, c. 1971 _________Plato II, A Collection of Critical Essays: Art and Religion, ed by Gregory Vlastos, Modern Studeis in Philosophy, Amelie Oksenberg Rorty, General Editor, Anchor Books, Doubleday and Company Inc., New York, c. 1971. “Plato: the State and the Soul,” Britannica, http: www.philosophypagescom/hy/2g.htm, The Philosophy Pages, by Garth Kememerling, 1997, 2011. “Plato’s Ethics and Politics in the Republic,” Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, First published April 1, 2003, substantive revision august 31, 2009, http://Plato.stanford.edu/entries/Plato-ethics-politics/ Chin, Jacqueline, “Plato’s Republic: Innder Justice, Ordinary Jautce and Just Action in the Polis,” published in Theroretical Ethics, http://www.bu.edu/wcp/papers/teth/teth/chin.htm 34 Kamtekar, Rachana, “Social Justice and Happiness in the Republic: Plato’s two Principles,” History of Political Thought, Vol. XXII. No 2, Summer 2001. Gandhi: Works by Gandhi: Gandhi, Mohandas K., The Story of My Experiments with Truth, tr. by Mahaen Desai, Dover Publication, c. 1983. _________ Truth is God:[Gleanings from the writings of Mahatma Gandhi] bearing on God, God-Realization and the Godly Way. by M.K. Gandhi, Published by Navajivan Mundranalaya, India, c. 1955 A few of the books by Gandhi that are published by the Gandhi Smriti & Darshan Samiti, New Delhi, where Gandhi was shot. I gave a major address there in 2006. Gandhi’s granddaughter was one of the commentators. The General Editor for these books Anand T. Hingorani, The books were reprinted in 1998. Capial and Labour The Law of Continence The Law of Love Modern V. Ancient Civilization On Myself The Sciene of Satyagraha To My Countrymen Other Works by Gandhi; 35 Gandhi M. K., The Law and the Lawyers, published by Navajivan Publishing House, Ahmadebad 14, 1962 Gandhi, M. K.,Quotes of Mahatma Gandhi, Gandhi Sahitya Bhandar, 2006. Books About Gandhi’s Works: I will mention here, only three of what I take to be the most important books: Ghosh, Indu Mala, Ahimsa: Buddhist and Gandhian. Indian Bibliographies Bureau, copublishers, Balaji Enterprises, Delhi, India, 1989, Fisher, Lewis, The Life of Mahatma Gandhi, New York, Harper & Row Publishers, c. 1983. Iyer, Raghavan, The Moral and Political Thought of Mahatma Gandhi, Second Edition, New York , Concord Grove Press, 1983. ________, Understanding Ghandi, ed by Usha Thakkar and Jayshree Mehta, Sage Publications, India, c. 2011, My Articles about Gandhi and Ahimsa: 2011 – “A Comparison of Confucius’ Notion of Ren as Human-Heartedness and InnerHumanity with Gandhi’s View of Ahimsa as Compassion” published in the E-Journal, Dialogue & Universalism, Volume II, No. 1/2011. 2011 – a reprint - “The Role of Virtue in Developing Trustworthiness in Public Officials,” involving a comparison of Gandhi’s and Aristotle’s writings that are germane to the subject, published in the Oxford Forum in 2007. The paper was reprinted, with the 36 permission of the Oxford Forum, for future publication in Carnegie Leaning/Nelson Education. 2008 – “Ahimsa and its Role in Overcoming the Ego From Ancient Indic Traditions to the Thought and Practice of Mahatma Gandhi” was published in The Icfai University Press, Vol. II., No. 4, October 2008, Hyderabad, India. 2007 – “Ahimsa: a Way of Life, A Path to Peace,” was published in a booklet, as part of the Gandhi Lecture Series and the UMass/Dartmouth Center for Indic Stdues. 2005 – “India’s Three Great Contributions and Influences in the World,” a publication of the World Association of Vedic Studies, WAVES, edited by Professor BhuDve Sharma. 2003 – “The Importance of Ahimsa: in the Yoga Sutra, in Gandhi’s Thought and in the Modern World.” was published in India’s Contributions and Influences in the world,” a publication of WAVES, ed. by BhuDev Sharma. 2003 – “Gandhi: Boundaries of the Self as They Affect Nonviolence and Peace,” published in “Contemporary Views on Indian Civilization,” a publication of the World Association of Vedic Studies, WAVES, edited by BhuDev Sharma, pp. 11 – 19. 2001 – “Non-harm and Love as Viewed by Immanuel Kant and Mohatma Gandhi,” published in The Journal of Religious Studies, Vol. XXXII, Nos. 1 & 2, Panjabi University, Patiala, India. 1996 - “Gandhi’s Ethical/Religious Tradition” (A Mode of Thought and Practices Which Have Influenced Many Contemporary Thinkers) published in the Journal of Religious Studies, Vol. XXVTI, Spring-Autumn, Nos. 1 and 2, Panjabi University, Patiala, India. 1991 – “The Role of Self-Discipline in the Process of Self-Realization,” and article written with Dr. Bala Sunder Rai Bhalla, a Reader At Panjabi University in which we 37 compare the ancient thought of Patnajali, the author of the Yoga Sutra with the thought of Gandhi with regard to the topic. Dr. Bhalla received his PhD in Gandhi Studies. The papers was published in the Journal of Religious Studies,Volume XVTFL, Spring, No. 6, Punjabi University, Patiala, India. A Book Which I am Writing on Gandhi and Ahimsa: Since my book on intuition was published in 2001, I have been working on a book, Ahimsa: a Way of Life; a Path to Peace, This book deals with the Gandhi’s thought and practice of ahimsa, the Hindu, Jain and Buddhist influence upon that thought and what is need to practice ahimsa in today’s world. I advocate a freeing of ahimsa from its Indic moorings so that it can be taught to and practiced by people of the world, especially children. I had a contract for the book in 2009 with Linus Publications of New York, but because of my husband’s serious illness leading to his death in 2011, I was unable to complete the book. However, I have written to the publisher, and I think that he is open to publishing the book when I complete it. I hope to do that in the next few months. Works on Hinduism, Jainism and Buddhism: I have taught these subjects for years, and my PhD is in Asian and Comparative Philosophy, so there are many, many books which I have read on these subjects. When teaching, I usually use: Koller, John, Asian Philosophies, which is published by Pearson, c. 2012, 2007, and 2002, 38 For the course on Jainism, I use: Jaini, Padmanabh S., The Jaina Path of Purification, Published by Motilal Banarsidass, c. 1998. Also, with Regard to a great Jain monk who had a profound effect upon Gandhi’s thought, I refer to: Mehta, Digish, Shrimad Rajachandra: a Life,Published by the Shrimad Rajchandra Ashram, Second Edition, c. 1991. 39