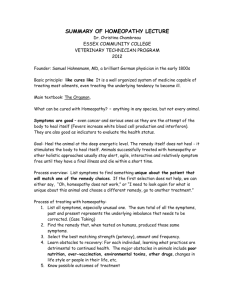

Chapter 4 Clinical Homoeopathy

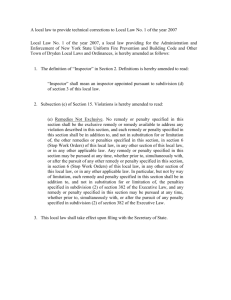

advertisement