Hyperthyroidism in Cats - Kingsteignton Veterinary Group

advertisement

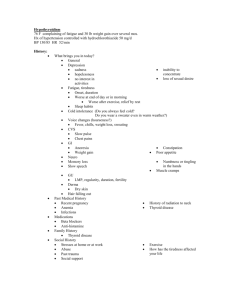

Hyperthyroidism in Cats What is hyperthyroidism? A cat has two thyroid glands which lie either side of the windpipe in the neck. These can become overactive, producing too much thyroid hormone. Usually thyroids become overactive due to non-cancerous changes. This often affects both thyroid glands, although one may be more severely affected. Rarely, changes can be caused by a cancerous growth. This can make treatment more complicated. How is hyperthyroidism diagnosed? A cat may be suspected of having hyperthyroidism based on the clinical signs it is showing. An enlarged thyroid gland is often palpable in the neck region. A blood sample is needed to make a definitive diagnosis. This checks levels of circulating thyroid hormones. Clinical Signs Thyroid hormones have an important role in controlling the body's metabolic rate. Usually affected cats are middle to old age. Cats with hyperthyroidism tend to burn up energy too rapidly and typically suffer weight loss despite having an increased appetite and increased food intake. Sometimes cats will show increased thirst, increased irritability, and restlessness. Occasionally cats may vomit or have diarrhoea. The increased levels of thyroid hormones cause the heart to beat faster. Over time the muscle of the heart can thicken. If left untreated, these changes can lead to heart failure. Once the underlying hyperthyroidism is controlled, the heart changes will often improve or resolve. Occasionally additional treatment may be required to control secondary heart disease. High blood pressure is another potential consequence of hyperthyroidism. This can lead to organ damage including retinal damage (which may lead to blindness), kidney damage, and damage to the heart or to the brain. Drugs may be needed to control blood pressure, but high blood pressure will often resolve with successful treatment of hyperthyroidism. Possible complications As mainly older cats are affected, it is not uncommon for hyperthyroid cats to have kidney disease as well. Hyperthyroidism tends to increase the blood supply to the kidneys, which may improve their function. Treating a hyperthyroid cat may unmask an underlying kidney problem. Because of this it is important that kidney function is monitored at the same time as thyroid levels. Occasionally, hyperthyroid treatment results in a decline in kidney function. If this is the case it may be necessary to reduce the dose of therapy so that the hyperthyroidism is not fully controlled but kidney function is not too severely compromised. Treatment options MedicalAnti-thyroid treatment can be given in tablet form. These control thyroid levels but are not a cure. There are currently two of these drugs on the market: Felimazole- recommended to be given twice daily Vidalta- recommended to be given once daily Both tablets must not be crushed. Tablets will normally bring thyroid levels down into the normal range within about 3 weeks. Blood tests are needed to check that the dosage is correct and treatment is lifelong. Side effects are uncommon. Occasionally treatment causes poor appetite, vomiting and lethargy. This generally resolves if the dosage of treatment is reduced or withdrawn. Rarely more serious side effects can occur, including anaemia, decreased white blood cell production, decreased platelet production, liver failure or skin irritation. If these occur, treatment must be withdrawn immediately. Blood tests are recommended to check thyroid levels, liver and kidney function and haematology (red blood cell count, white blood cell count and platelet levels) at regular intervals. These are quite frequent during the stabilisation period as this is when most side effects will be seen. The current recommendations (as advised by the drug manufacturers) are that cats on Felimazole have blood samples taken before treatment starts then at 3 weeks, 6 weeks, 10 weeks, 20 weeks and thereafter every 3 months. For cats on Vidalta it is recommended that bloods are taken before treatment starts then at 3 weeks, 5 weeks, 8 weeks and thereafter every 3 months. SurgicalIt is possible to surgically remove the affected thyroid gland. This is normally done after initial stabilisation on medical treatment for 3 or 4 weeks. Sometimes both glands are affected. If this is the case one gland is normally removed first with the second gland being removed 6-8 weeks later. Sometimes a cat can remain hyperthyroid even when both glands have been removed. This is because occasionally thyroid tissue can be found elsewhere in the body (usually inside the chest). A possible complication of surgery is damage to the parathyroid glands, which sit in the capsule surrounding the thyroid. These are important for regulating calcium levels in the body. To minimise the risk of damaging the parathyroid glands, the surgeon will try to preserve the thyroid capsule where the parathyroid gland sits. Occasionally this can mean some thyroid tissue is left behind, which can eventually regrow (over a couple of years). Damage to the parathyroid gland is less serious if only one gland is operated on, as the gland on the other side can compensate. If both sides are operated on and both parathyroid glands damaged, there is a risk of low blood calcium. This can be life threatening and may require lifelong supplementation with calcium and vitamin D. Radioactive iodine therapy Radioactive iodine is an effective cure for hyperthyroidism whatever the location of the overactive thyroid tissue. A single injection of radioactive iodine is curative in around 95 per cent of all hyperthyroid cases, and in the few cats where hyperthyroidism persists the treatment can be repeated. Occasionally a permanent reduction in thyroid hormone levels (hypothyroidism) occurs following radioactive iodine treatment, and if this is accompanied by clinical signs (lethargy, obesity, poor haircoat) then thyroid hormone supplementation may be required (in the form of tablets). Radioactive iodine is administered as a single injection given under the skin. The radiation destroys the affected abnormal thyroid tissue, but does not damage the surrounding tissues or the parathyroid glands. The radiation carries no significant risk for the patient, but protective measures are required for people who come into close contact with the cat. For this reason, the treatment can only be carried out in certain specially licensed facilities and a treated cat has to remain hospitalised in isolation until the radiation level has fallen to within acceptable limits. This usually means that the cat must be hospitalised for between three and six weeks following treatment.