Feline Hyperthyroidism: Not Just A Skinny Old Cat

advertisement

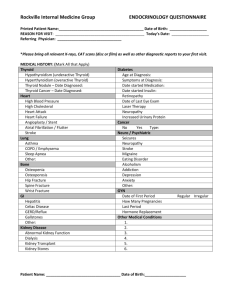

Feline Hyperthyroidism: Not Just A Skinny Old Cat! By Katherine Dodds, DVM Feline hyperthyroidism is one of the most common endocrine disorders of older cats. Despite that, veterinarians have only known about the disorder since 1979. We still do not know what causes this disease but suspect an environmental or dietary origin. The other possibility is that since veterinarians were unaware of the disorder, skinny old cats were just that—skinny old cats or cats with heart disease or eye problems were just unlucky. And no one had ever thought to take the blood pressure on a cat so that problem was just ignored. But now we know, cats frequently get benign thyroid tumors that pump out thyroid hormone. This essentially revs up the cats metabolism resulting in an increased heart rate (and subsequent cardiac problems), hypertension, weight loss, increased appetite/thirst, eye problems, sleep disorders, vomiting, diarrhea, almost you name it. The classic hyperthyroid cat is one that is older (average 13-14 years old) who starts losing weight despite a ravenous appetite and has a nervous disposition. You can almost spot these cats from across the room. But, unfortunately, they do not all present that way and other diseases can mimic hyperthyroidism. Some cats stay overweight, do not have a ravenous appetite but develop cardiac disease. We call these more difficult cases “occult” or hidden hyperthyroidism. Diagnosis has also evolved with our understanding of this disorder. Originally we just tested for the levels of thyroid hormone (T3 and T4-with T4 being more reliable). Then with the recognition of occult hyperthyroidism we needed more sophisticated tests. An old test for human patients, the T3 suppression test, has consistently proven to be very useful in diagnosing occult hyperthyroidism. We administer T3 orally (pill form) to the patient for several days after a baseline sample then take a post T3 sample (pay attention to the timing!). We then determine if the thyroid properly suppressed (stopped producing thyroid hormone once too much was around). A normal thyroid will stop producing hormones if it detects too much in the bloodstream. In a normal thyroid the post T3/T4 sample will have a very high T3 (because you’ve given it to the cat for 3 days) and a very low T4 (because the thyroid has stopped producing it in response to the high T3). So even occult cases can be diagnosed and screening T4 has become pretty routine for the diagnosis of early cases in geriatric felines. So on to treatment. There are three routes to treat hyperthyroidism. Medical, surgical and radioactive iodine therapy. Medical management involve the administration orally of anti thyroid drugs. The most commonly used is Tapazole (Methimazole). This drug has the advantage of being relatively inexpensive and with reversible effects. It has the disadvantage of owner compliance (it is hard to pill a cat 1-3 times a day) and side effects. A number of my patients developed facial itching and really scratched their faces up badly. Other complaints are usually G.I. (about 10%!). So on to surgical management. First we stabilize with Tapazole so the patient is not such a high anesthetic risk and then we surgically remove the affected thyroid(s). This approach is less expensive then radioactive iodine but involves anesthesia in an aged animal, and, if both thyroids are removed, carries the risk of hypothyroidism (too little thyroid) and hypocalcemia (too little calcium). The low calcium is a dangerous but temporary problem but the hypothyroidism can be an issue for a client who has already had trouble giving pills. These cats need lifelong oral thyroid supplementation. So on to radioactive iodine. This has long been considered the gold standard (best way) to treat hyperthyroidism. It is expensive but safe and permanent. The only other drawback is that the pet needs to stay in a special facility until the radioactivity wears off (usually about a week). Sometimes we need to supplement with thyroid hormone after radiation treatment as we have now completely wiped out the thyroid gland; I view that a small price to pay. Radiation therapy has come a long way in the last few years and is now considered the standard of treatment. Just when we thought we had all the treatment options in order for the client to decide what is best for their situation, pocketbook, etc. another problem rose up to complicate things. Kidney disease. Kidney disease is also very common in older cats. And come to find out, with the advent of such early detection tests and routine screening, that often hyperthyroidism can mask kidney disease. It does this by keeping the pet’s blood pressure (and therefore blood flow through poorly functioning kidneys) high and therefore improving kidney function. Your hyperthyroid cat MUST be monitored for kidney disease both before and during treatment for hyperthyroidism. So what do you do if your cat is diagnosed with kidney disease and hyperthyroidism? Here is where the “art of medicine” comes in. You and your veterinarian will cautiously decide which disease is causing more of a problem. If mild hyperthyroidism is keeping kidney disease in check and the patient’s cardiac function seems pretty good, then leaving the early hyperthyroid case with elevated thyroid hormones will keep the kidneys functioning better. The cat will have a better quality of life mildly hyperthyroid than in end stage renal failure. If the heart disease is more severe (risk for sudden death) than the hyperthyroidism must be treated and the kidney disease monitored. These cases would not be the best for surgical or radioactive iodine therapy as neither of these are reversible. And for all those cases somewhere in between? You and your veterinarian may choose to partially treat your cat with oral therapy, manage the heart disease with drugs, manage the kidney disease with diet and monitor everything closely. We can’t cure all but we can do our best to give your oldster as much quality time as possible.