Husbandry of the black jelly, Chrysaora achlyos, a newly

advertisement

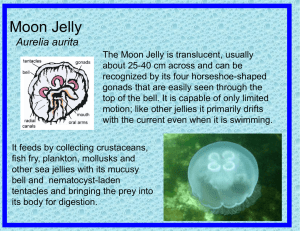

Husbandry of the black jelly (Chrysaora achlyos), a newly discovered scyphozoan in the eastern North Pacific Ocean Maintenance de la Méduse Noire (Chrysaora achlyos), un scyphozoaire récemment découvert dans le Nord-Est de l’océan Pacifique M. SCHAADT1, L. YASUKOCHI2, L. GERSHWIN3, D. WROBEL4 1 Cabrillo Marine Aquarium, San Pedro, CA 90731, USA 2 Birch Aquarium at Scripps, La Jolla, CA 92093, USA 3 University of California, Berkeley, CA 94706, USA 4 Monterey Bay Aquarium, Monterey, CA 93940, USA ABSTRACT The black jelly (Chrysaora achlyos) has been reported four times in the 1900’s. First described in 1997, it is believed to be the largest invertebrate named this past century. During the summer of 1999, adult medusae washed ashore in large numbers near San Diego, California, USA, and as far north as Los Angeles, California. Gametes were harvested from mature medusae. In vitro fertilization resulted in the planula, polyp, and ephyra stages being seen for the first time. Successful husbandry protocols have resulted in ephyrae growing into young medusae kept in modified aquaria for public display. Husbandry techniques developed during this study can be used to add new schyphozoan cultures to the growing list now available to public Aquariums. RÉSUMÉ La Méduse Noire (Chrysaora achlyos) a été signalée à quatre reprises au début du siècle. Décrite pour la première fois en 1997, elle serait la plus grande espèce d’invertébré découverte au XXe siècle. Durant l’été 1999, des méduses noires adultes s’échouèrent en grand nombre sur une zone s’étendant de San Diego à Los Angeles, Californie, USA. Des gamètes furent récoltés sur des spécimens adultes. De leur fertilisation in vitro résultèrent successivement des planules, des polypes, puis des éphyrules observées pour la première fois. Grâce à un protocole d’élevage approprié, les éphyrules grandirent pour devenir de jeunes méduses, présentées au public dans des aquariums adaptés. Les techniques d’élevage développées pour les besoins de cette étude peuvent être reproduites pour que cette espèce s’ajoute à la liste grandissante des scyphozoaires présentés dans les Aquariums publics. Bulletin de l’Institut océanographique, Monaco, n° spécial 20, fascicule 1 (2001) Black Jelly Chrysaora achlyos During the summer of 1999, dozens of large scyphozoan medusae (Fig. 1) washed ashore in San Diego and Los Angeles, California. This was the fourth time in the 20th century this medusa was reported in the literature (Crowder, 1926; Halstead, 1965; and Martin and Kuck, 1991). The medusa was first described by Martin et al., in 1997 and named Chrysaora achlyos (achlyos - after the Greek god of obscurity). The holotype specimen (Acc. No. 89.28.1) is in the preserved specimen collection of Cabrillo Marine Aquarium (CMA). It is commonly referred to as the black jelly due to the dark burgundy coloration of the bell. It is believed to be the largest invertebrate named during the 20th century reaching bell diameters of over 1 m and oral arm lengths of over 10 m. In vitro Fertilization During the 1990’s, in-vitro fertilization procedures were performed on moon jellies (Aurelia spp.) and purple-striped jellies, Chrysaora colorata (previously known as Pelagia colorata – see Gershwin and Collins, 2001) at CMA. When black jellies washed ashore in 1999, the same techniques were employed by staff and volunteers at CMA and at Birch Aquarium at Scripps in San Diego in collaboration with a researcher from University of California Berkeley. Small bits of gonadal material were taken with forceps from the subgenital pit area of mature adult medusae. The sex of the individuals was confirmed using a dissecting microscope (Fig. 2). Eggs are easily seen as spheres embedded in the female gonadal tissue. Sperm are inside oddly shaped packets giving the male gonadal tissue a uniform, granular appearance. Eggs and sperm were combined in petri dishes with filtered seawater and kept covered on a water table at 15 degrees centigrade. Within 48 hours, planulae were observed slowly rotating through the water. The planulae were removed to a small jar with a Plexiglas plate lying at an angle against the side. Within the next 48 to 96 hours, planulae settled on the underside of the plate (Fig. 3). Planulae and polyps were shared with the Monterey Bay Aquarium. Life Cycle The life cycle of the black jelly is similar to other scyphozoans in that a freeswimming medusa stage alternates with an attached polyp stage. Polyps clone new polyps by producing podocysts. At certain times of the year some polyps undergo a form of cloning called strobilation, resulting in the release of ephyrae. The newly released ephyrae are about 1-2 mm in diameter and closely resemble ephyrae of purple-striped jellies. Ephyrae have been grown to adult medusae with 20 cm bell diameters, 50 cm long oral arms, and 100 cm long tentacles. The adult medusae bell and frilly oral arms have light brown to dark burgundy pigmentation with long pale tentacles (Fig. 4). Bulletin de l’Institut océanographique, Monaco, n° spécial 20, fascicule 1 (2001) Husbandry Feeding Newly settled polyps are kept in filtered, 15° C seawater in a closed system jar with daily 100% water changes. After the first week, they are put into a jar filled with Rotorich enriched rotifers (Brachionus sp.) for about one hour per day then returned to a closed system jar with clean seawater and a small amount of rotifers. This method helps keep water quality within acceptable limits. At about one month old, they are put into a tank with flowing seawater at 15° C and their diet is supplemented twice a day with Super Selco enriched brine shrimp (Artemia sp.). Care is taken not to overfeed, which seems to allow for growth of opportunistic organisms (like diatoms, polychaete worms, and hydrozoan or other scyphozoan polyps) that will out-compete or overgrow black jelly polyps. Under lab conditions, strobilaton first occurs when the polyps reach one to four months of age (Fig. 5). Newly released ephyrae (Fig. 6) are removed from the polyp tank and kept in closed system jars with gentle bubbling to keep ephyrae suspended. The water is changed at least every other day. Prior to changing the water the ephyrae are removed to a small finger bowl and allowed to feed on highly concentrated, enriched rotifers and finely chopped moon jelly mesoglea for about one-half hour. The mucus producing epithelial layer of the moon jelly bell is removed with a strong spray of seawater thus reducing the chance of entrapping tiny, feeding ephyrae. After feeding for about one-half hour, the ephyrae are put back into closed system jars with filtered seawater. A small amount of rotifers are kept with the ephyrae to allow feeding between water changes. At the post-ephyra stage (Fig. 7), about one month old or when the bell develops and oral arms become evident, the diet is supplemented with moon jelly ephyrae and larger pieces of adult moon jelly bell. The post-ephyrae are removed to a finger bowl and given the opportunity to feed for about one-half hour then moved back into jars with filtered seawater. Again a small amount of rotifers are kept with the post-ephyrae to allow feeding between water changes. Juvenile medusae (1-7 cm in bell diameter) (Fig. 8) are fed larger pieces of moon jelly as well as moon jelly ephyrae and enriched brine shrimp nauplii. Tank Requirements Plates with attached polyps are suspended in a small (1 L) clear plastic box. The overflow empties into a smaller clear plastic box with a screen prior to the overflow so as not to lose ephyrae. Newly released ephyrae are moved into small (1.5 L), round, clear plastic containers. These round containers have an air source that delivers small bubbles that help keep the ephyrae suspended. Juvenile medusae (1-3 cm bell diameter) are kept in small (20 L) acrylic aquaria that are modified to serve as pseudokreisels. Young adults (7+ cm bell diameter) are on public display in a stretch planktonkreisel (1 m tall, 2 m long and 28 cm front to back) (Fig. 9). Bulletin de l’Institut océanographique, Monaco, n° spécial 20, fascicule 1 (2001) Compatibility With Other Jellies Medusae of purple-striped jellies are raised together with black jellies once they reach a bell diameter of about 2 cm. Safety Nematocyst patches are obvious in the ephyrae stage of the black jelly but not dangerous to humans. Adult black jelly medusae stings deliver less potent venom than Chrysaora quinquecirrha, a phylogenetic congeneric cousin (Radwin, Gershwin and Burnett, 2000). Life Span Black jellies can be grown from ephyrae to young adults in 2 to 6 months, depending on the intensity of feeding and cleaning efforts. Once the young adults reach bell diameters of about 15 to 20 cm, the bell shows signs of deterioration and begins to shrink. We are investigating this phenomenon and at this time we believe that upon reaching about the inside dimension of the stretch planktonkreisel (Hamner, 1990), the jellies touch surfaces much of the time which results in bell tissue damage and inefficiency of feeding efforts. Future We are planning for the future. Polyp Cultures Polyps on the plates have continued to produce podocysts. Podocysts eventually grow into new polyps (Fig. 10). This cloning of polyps has been very slow resulting in few new polyps. New polyp plates can be sent to other aquariums to start their culture. In-vitro of Tank-raised Medusae We are continuing our efforts at in-vitro fertilization of the tank-raised medusae. To date, we have successful fertilization events but very few planulae and no settled polyps. We will continue efforts at in-vitro fertilization with the goal of producing more polyp plates, some of which can be shared with aquariums, zoos and other educational institutions. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The authors extend their appreciation to Freya Sommer who taught us invitro fertilization techniques for scyphozoans, Stephane Hénard who graciously provided the French translation of the title and abstract for this paper, to Norbert Wu for Figure 1, and to Gary Florin who provided many of the photographs. Bulletin de l’Institut océanographique, Monaco, n° spécial 20, fascicule 1 (2001) REFERENCES CROWDER, W., 1926.- The life of the moon-jelly-. Nat. Geogr. 50:187-202. GERSHWIN, L. and A.G. Collins, Apr. 2001.- A preliminary phylogeny of Pelagiidae (Cnidaria: Scyphozoa), with new obervations of Chrysaora colorata comb-. J. Nat. Hist. HALSTEAD, B.W., 1965.- Phylum Coelenterata-. Poisonous and Venomous Marine Animals of the World, vol. I. Invertebrates. U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington, D.C. 994: Plate 43. 297-535 pp. HAMNER, W.N., 1990.- Design developments in the planktonkreisel, a plancton aquarium for ships at sea. J. Plank. Res. 12 (2): 397-402. MARTIN, J.W., L. GERSHWIN, J.W. BURNETT, D.G. CARGO, and D.A. BLOOM, 1997- Chrysaora achlyos, a remarkable new species of scyphozoan from the Eastern Pacific-. Biol. Bull. 193: 8-13. MARTIN, J.W., and H.G. KUCK, 1991.- Faunal associates of an undescribed species of Chrysaora (Cnidaria, Scyphosoa) in the Southern California Bight, with notes on unusual occurrences of other warm water species in the area-. Bull. South. Calif. Acad. Sci. 90 (3): 89-101. RADWIN, F., L. GERSHWIN and J.W. BURNETT, 2000- Toxinological studies on the nematocyst venom of Chrysaora achlyos. Toxicon-. 38:1581-1591. Captions for figures Figure 1. Chrysaora achlyos, the black jelly with adult garibaldi. Figure 2. Gonads of C. achlyos. (a) gonadal tissue with eggs. (b) gonadal tissue with sperm in packets. Magnification of both photographs is 40X. Figure 3. Newly settled polyps of C. achlyos. Magnification is 100X. Figure 4. Young adult C. achlyos medusa. Figure 5. Strobilating polyps of C. achlyos. Magnification is 40X. Figure 6. Ephyra of C. achlyos. Magnification is 50X. Figure 7. Post-ephyra of C. achlyos. Magnification is 20X. Figure 8. Juvenile medusa of C. achlyos. Magnification is 4X. Figure 9. Young adult C. achlyos medusae on public display in a planktonkreisel. Bell diameters are 15cm. Figure 10. Polyps and podocysts of C. achlyos. Magnification is 40X. Bulletin de l’Institut océanographique, Monaco, n° spécial 20, fascicule 1 (2001) Bulletin de l’Institut océanographique, Monaco, n° spécial 20, fascicule 1 (2001) Bulletin de l’Institut océanographique, Monaco, n° spécial 20, fascicule 1 (2001) Bulletin de l’Institut océanographique, Monaco, n° spécial 20, fascicule 1 (2001)