Transforming Learning Cultures in Further Education Project

advertisement

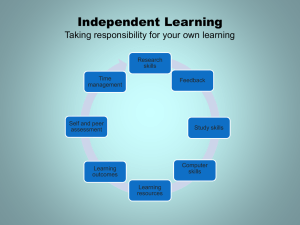

LE_PMH_DOC_09.12.02 Transforming Learning Cultures in Further Education Project (TLC FE Project) BRIEFING PAPER 2 The Cultural Dimension of Learning in FE December 2002 This project is part of the Economic and Social Research Council’s Teaching and Learning Research Programme (TLRP). Summary Our research into 16 widely differing sites for learning in Further Education (FE) has confirmed the enormous diversity of the provision in the sector. The differences are multi-facetted, and those facets are inter-related in complex ways. These cultural relationships appear to be fundamental to the success or otherwise of teaching and learning. Consequently, it is necessary to add a cultural dimension to current policy and practice thinking. The project is also pioneering ways to increase research capacity in FE, through the involvement of FE Colleges and FE College staff as full participating partners in the research. It is in addition developing means of integrating quantitative data with 16 qualitative case studies. Introduction We have now completed the first 18 months of a four and a half-year research project investigating the ways in which learning in Further Education (FE) can be improved. From the outset, our focus has been on the opportunities and barriers for the transformation of learning cultures in the sector. In this paper, we describe: the partnership arrangements of the project and their contribution to building research capacity in the sector; our broad methodological approach, including the integration of multiple case studies with questionnaire data; some of our early findings about the significance of a cultural dimension in understanding and improving teaching and learning. Much of what follows is provisional, and will be further refined as the research continues. 1 LE_PMH_DOC_09.12.02 Methodology Detailed fieldwork is taking place in 16 learning sites, four in each partner FE college (See Below). The sites are deliberately varied, and are as follows: Administration, business and technology NVQ levels 2/3 Administration & IT (14-16 year olds; certification) Advanced Vocational Certificate in Education Travel and Tourism BTEC National Diploma in Health Studies CACHE Diploma (nursery nursing) C& G. Information Technology (by distance learning)/ GNVQ Information Technology1 ‘Connect 2’ course for school leavers with learning difficulties English for Speakers of Other Languages (roll on, roll off) Entry Level Drama GNVQ Intermediate Business Studies IT Quick Skills (Roll on, roll off) Mature students support, in learning centre National Certificate in Electronics and Telecommunications (2 years; day release) Pathways for Parents (reengagement course for young parents) Photography (BTEC levels + City & Guilds; 2 years full or part time) Psychology AS level/Modern languages AS level2 Within each site, tutors and a sample of students are interviewed twice a year; all students in each site complete a questionnaire at the start of each year and on exit from the site; sessions are regularly observed; tutors keep research log books/diaries; photos and videos are taken; relevant documents (site based, college based and national) are collected and analysed. Research Capacity Building through Partnership Research The TLC project is a partnership between four universities (Exeter, Leeds, West of England and Warwick) and four FE colleges (St. Austell, Park Lane, City of Bristol, City College Coventry). In order to extend this partnership into all aspects of the research, the project is staffed across all eight institutions, as follows: 16 participating tutors (1 for each site), each with about 2 hours per week timetable remission 4 FE-based seconded research fellows, each working 0.4 of their time on the TLC 5 University-based researchers, each working 0.5 of their time on the TLC 5 University-based Directors, each working one day per week on the project. The project research staffing is thus 30 people, all of whom are part-time, and whose involvements in the project are diverse. This has presented challenges in relation to management, cohesion and team building, but also brings an invaluable range of perspectives and expertise to our work. The quality of the research has been enhanced by the insights and understandings of the FE practitioners. In turn, they are also learning about their own sites, for example through data accessing learners’ perceptions; about teaching and learning more generally; about the conduct of research and about the contribution research can make to improving FE practice. This enhanced research capacity is already impacting upon the practices of some participating tutors, and is being gradually spread wider into the partner colleges, and into regional and national FE communities, for example through our close working 1 2 The change here arose from the closure of the C&G course at the end of the first year. The change here was because a participating tutor left the partner college, at the end of the first year of fieldwork 2 LE_PMH_DOC_09.12.02 relationships with the Learning and Skills Development Agency (LSDA) at both national and local levels. However, there are major external pressures upon research capacity, which lie outside the influence and control of the project. Two of the partner colleges have gone through major mergers during the first year. Another has had two largely successful inspections (general and area), and is currently undergoing major restructuring. In the FE sector more generally, there are pressures of funding, inspection, changed curricula and assessment, changing government policy, new LSC procedures and so forth. Such pressures can limit opportunities for engagement with research findings and activities, though can also create new opportunities. The impact of these pressures on teaching and learning is being studied, as part of our research. Learning Cultures, innovation and transformation When we analysed the data collected during the first year of fieldwork, we were struck by the variations between the 16 sites. These differences are far from trivial and superficial. The ways in which they achieved learner success varied significantly, as did some of the issues and problems that they faced. Each site had a strong culture, of which students and tutors were constituent parts. The culture of vocationally-oriented sites also appeared to be significantly influenced by the occupational culture of the jobs for which students are being prepared. These different aspects of learning site culture were closely interrelated, and the effects of teacher actions depended upon those interrelationships. Sometimes, these aspects were acting in a positively synergistic manner. On other occasions, there were tensions. In one site, for example, tutors’ and students' expectations were very different. In another, both students and tutors were cynical about the relevance of the content of the course. In yet another, learning success appeared to depend almost completely on tutor actions that lay outside the official job description, resourcing and quality mechanisms. As well as differences between sites there are also patterns of resemblance. One of our next activities will be to analyse and report upon the extent to which we can group sites into families, with similar learning cultures. This should make it easier to draw out meaningful guidelines for improving learning in the sector. One approach to this is through use of the questionnaire data. This suggests three groups of sites, characterized by differences in the extent of discussion of ideas amongst students, and the extent of negotiation of the course between students and tutor. We are now exploring ways in which these groupings can be more deeply understood through the case study data. We are also exploring ways in which the juxtaposition of case studies about the sites in each group might encourage the development of new insights for the case studies themselves. An on-going focus of activity is the developing learning careers of the students in each site. We are concerned both with the ways in which students contribute to the nature of the sites, and also the ways in which teaching and learning in the sites impacts upon them, their developing careers and their construction of their identities. All 16 participating tutors are currently making changes to the work in their sites. Some of these changes result from our early findings. One tutor, for example, is trying to increase the autonomy of the students, as well as reducing the burden on herself, by carefully limiting the extent and type of help that she gives. Other changes arise from tutors’ own professional judgments, independently of research evidence. Yet others are forced by changes in external circumstances. Some changes are around teaching and teacher activity, others impact on other aspects of culture. For example, at least two sites are changing entry criteria for their courses. 3 LE_PMH_DOC_09.12.02 Through the next year, the research will continue to monitor and evaluate the impact of these changes, as well as those not originating from tutor activity. This is likely to produce clear indications of what works and why, and will build a rich understanding of the relationship between planned and unforeseen changes in the cultures of the sites. In doing this, we will be able to say more about the varied nature of transformations in FE learning cultures. Later in the project, we hope to give pointers to ways in which positive transformations can be supported and made more likely. Implications for Practice: Taking Learning & Teaching Cultures into account In all 16 sites, culture seems very important. Yet this dimension appears to be largely missing in current FE policies and debates. In particular, Aspects of what can be defined as good teaching and learning differed significantly from site to site. Approaches that were appropriate in one would be quite inappropriate in another. Yet the FENTO Standards and OFSTED criteria for inspection implicitly assume that good teaching and learning have essential common characteristics in most if not all situations. It seems that good teachers work to influence the cultures of the sites where they teach. They are skilled in judging what will work within those cultures, and what will not. In no site was teaching and learning always smooth and unproblematic. Teachers had to work out what to do, if the balance of a group was disrupted. Sometimes this took even the most experienced teachers into uncharted waters. Constructing solutions, in such complex circumstances, was rarely a technical process. Meeting individual students’ needs depends upon the cultural context of the site. Such needs have to be balanced by the wider needs of the student group as a whole, and for the cultural maintenance of the sites. Individual needs were altered by and contributed to the site cultures, rather than being simply located in them. Problems occurred if a minority of students wanted something that conflicted with the dominant culture of a site, or with the needs/wants of other students in the site. This was a more significant issue where group cohesion was a valued part of the site culture. Site culture strongly influences the impact and effectiveness of any measures taken to improve teaching and learning. Put differently, improving teaching and learning often entails enhancing a particular learning culture. There is an urgent need for policy makers and college managers to address these issues of cultural diversity. The project can be expected to help these and other stakeholders to constructively engage with this diversity. Contact Details, for further information Project website: http://www.ex.ac.uk/education/tlc Hilary Olek, Project Administrator University of Exeter St. Luke’s Campus Heavitree Rd. Exeter EX1 2LU Tel: 01392-264910/264865 Fax: 01392-411274 e-mail: H.E.Olek@ex.ac.uk 4