Perspectives on Qualitative and Quantitative Research in Education

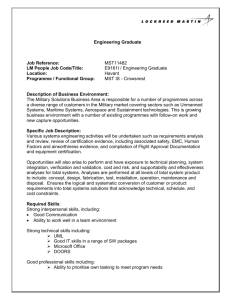

advertisement

1 Perspectives on Qualitative and Quantitative Research in Education M Cecil Smith Northern Illinois University Introductory remarks for a presentation given at the 21st annual Midwest Research-toPractice Conference in Adult, Continuing, and Community Education October 9-11, 2002 DeKalb, IL http://www.cedu.niu.edu/reps/midwest.htm 2 Perspectives on Qualitative and Quantitative Research in Education I, along with my NIU colleagues, Tom Smith, Nadine Dolby, and Hide Shimizu, want to talk about the role of research training in graduate school, the different ways that such research training occurs for students, and some important issues that graduate students should be knowledgeable about—particularly in regards to the increasing demands for students to have more sophisticated research skills. These demands arise, in part, because of the recognition that the kinds of problems that educators must confront are very complex and cannot be solved without understanding how social, economic, cultural, political, and individual factors interact to create the kinds of conditions seen in schools and communities. This topic is particularly important at a conference such as this that focuses on translating knowledge from the research laboratory (in whatever form it may be) to the arena of practice in schools and communities. Each of the four of us want to spend a few minutes describing what we think are some key issues in graduate research training, and tell a bit about what we try to do here in our College of Education in preparing graduate students to become not only consumers but producers of research. We will not claim that we are necessarily training graduate students better or differently from other colleges of education. In fact, surveys show that graduate training in research methods across colleges of education is remarkably similar (Mundfrom, Shaw, Thomas, Young, & Moore, 1998). As you might guess, however, doctoral students do tend to get more training than masters students, and that graduate 3 students at research institutions receive more training than those at comprehensive universities. I teach an introductory course to research methods in education, as does my colleague, Tom Smith. Although I’ve taught this course every semester for about 12 years, I still find it a challenging course to teach. There are at least three reasons for this. The first reason is that graduate students often come into the course very wary about having to learn about research. My experience is that students tend to view research as an esoteric activity that is not very relevant to what they do--or want to do--as practitioners. They don’t see research as important to informing and improving their skills and knowledge as teachers, counselors, and administrators. The second reason has to do with “math anxiety,” or more accurately, a fear of learning about statistics (as if quantitative methods were the only approach to educational research). A few have heard about this thing called qualitative research and hope desperately that we’ll focus only on that and disregard the numbers. Of course, we want them to learn a variety of approaches to doing research, to understand that there are a variety of “tools” that one can apply, and that the method one selects is very much a function of the particular problem being investigated, how one frames the problem, and one’s philosophical orientation about the nature of knowledge, truth, and certainty. These are not simple issues and therefore it follows that the selection of a research method is not something that is done casually. The third reason has to do with what we try to accomplish in this single, 16-week course. We attempt to teach graduate students how to be critical and informed consumers 4 of educational research—a basic skill that we believe is essential for all educators. So, we spend a lot of time reading and critiquing studies of various sorts, thinking about the value of these studies and how they contribute to the scientific knowledge base, and the practicality of the findings for teachers and administrators. But, we also want to teach them the basics of how to do research so that they can: • ask a “good” research question • distinguish among different types of variables • recognize the differences between probability and non-probability sampling methods • understand the role of measurement in research • distinguish among different data-gathering methods • evaluate the advantage and disadvantages or strength and weaknesses of different types of research: descriptive, correlational, group comparison (including experiments), and qualitative and quantitative approaches • understand some basic data analysis methods (both qualitative and quantitative) • make connections between research findings and practical matters in regards to teaching, learning, and assessment. Clearly, this is a lot to accomplish in a short amount of time. At best, students leave the course with some “fuzzy” knowledge of a few basic concepts and (we hope) the recognition that there is much more that they need to do to develop their research skills. Unfortunately, due to the reluctance to increase credit-hour requirements in different 5 graduate programs, some students may not have further coursework in research methods or statistics. A few may have opportunities to work as research assistants. Some masters students, and all doctoral students, will of course face the task of having to do an original piece of research—the thesis or dissertation. Most of us find it troubling that many students begin this task not well prepared to undertake or complete it. Still other students will be presented with opportunities to do research, or to be involved in research in their schools, classrooms, counseling centers, and other worksites. Therefore, many of the graduate students whom we set out to train to be consumers of research will evolve into those persons who produce research. On top of all this course content, we add yet another layer in the introductory course. We emphasize that research has a largely social dimension to it. Research topics are determined in that space occupied by the individual’s intellectual curiosity, their perception of a particular problem, and their understanding of some social or educational need. Researchers often collaborate with one another because even fairly simple studies are very labor-intensive, and require multiple participants to organize and carry out the work. Sometimes, it really is true that “two heads are better than one,” and collaborative research activities result in more insightful, even groundbreaking studies. Certainly, researchers also share with one another (and the general public) what they have learned through publications and conference presentations. So, social science in education is very much a social enterprise. 6 Thus, we create a variety of different learning opportunities in the course for students and we either require or encourage them to: • work together in small research teams to identify a problem that is of common interest, to research and write collaboratively (in ways that approximate the collaborative activities of many scholars) • attend research conferences, graduate colloquia, and dissertations defenses (and to evaluate these) in order to hear about research first-hand, • interview educational researchers at other institutions to learn more about their work and motivations, • read and critique published research, and to do these things while simultaneously developing their own research questions and appropriate methodologies for addressing their questions. There are great challenges to learning about educational research. Social and educational problems are seemingly more complex, and the methods and tools developed to address some of these problems are, likewise, more sophisticated. It is not enough for graduate students, who aspire to professional practice in their respective fields, or to produce original research themselves, to complete their programs of study with only a minimum of research training. Thus, our goal is to create a forum for discussion among those who teach research methods to seek out ways to reform graduate preparation in social science research for education, making it more effective and efficient, and better suited to the complex demands of society. 7 References Mundfrom, D.J., Shaw, D.G., Thomas, A., Young, S., & Moore, A.D. (1998, April). Introductory graduate research courses: An examination of the knowledge base. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the American Educational Research Association, San Diego.