West Midlands Post-Roman Research Agenda

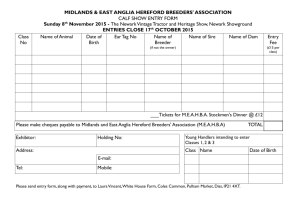

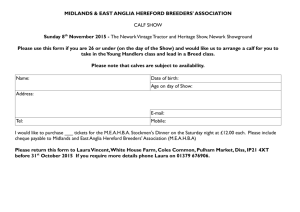

advertisement

West Midlands Regional Research Framework for Archaeology, Seminar 4: Vince 1 West Midlands Post-Roman Research Agenda: Ceramics Alan Vince alan@postex.demon.co.uk Raw data The West Midlands in the 5th to 11th centuries was a border region between the British/Welsh west in which pottery was not in common use (for example, the only pottery found at the princely site of Dinas Powys was imported, 1963) and the AngloSaxon south and east in which pottery was in common use, both for domestic and ritual purposes. This east-west trend existed in the early Anglo-Saxon period but continued into the mid and late Saxon periods. Thus, although pottery was used by the late 10th or early 11th centuries in Hereford, for example, none of that pottery was locally-made and the quantities in which it is found suggest that pottery was used less intensively than further east. Appendix 1 lists those sites from which pottery of 5th to mid 11th-century date has been recorded. Clearly, with the increase in field archaeology generated by the planning process there is likely to be a lot more material in museums and archaeological unit stores than is listed here but the general paucity of finds and the east-west trend is clear. Alternative Chronologies As a result of the small number of sites, and the lack of independent dating evidence, there is a great danger of circular argument concerning the cultural and ethnic associations of the finds and their dating. Ideally, we should be able to use C14 or dendrochronological dating to provide a chronological framework and only then look at the fabric, typology and decoration of the pottery to establish cultural affiliations. Since this is at present not possible the entire interpretative framework used here may prove to be wrong. Primary Research Aim The primary research aim for the study of 5th to 11th-century pottery in the West Midlands is therefore to recover pottery from stratified assemblages which can be dated by C14, dendrochronology or other associated artefacts, although strictly speaking the same reservations about circularity in reasoning affect those artefacts as much as pottery. Secondary Research Aims In the remainder of this document I have no option but to use traditional culturalhistorical interpretations which are based on sources such as the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, which were in some cases compiled centuries after the events they record and which were written mainly from a polarised perspective (Christian vs Pagan, Anglo-Saxon vs British/Welsh). Page 1 of 19 West Midlands Regional Research Framework for Archaeology, Seminar 4: Vince 2 5th to 7th-century ceramics Continuation of Romano-British wheelthrown pottery tradition One of the contentious issues concerns the ending of the Romano-British pottery industry. At various times Rahtz, for example, has suggested that some of the wheelthrown greywares found on sites such as Cadbury, Congresbury, are not residual Roman but locally-made sub-Roman products. If we accept the evidence from sites such as Wroxeter for the continuation of Romanised culture into the 5th and 6th centuries in this region then why should pottery not have continued to be made? However, no such pottery has been published from the Wroxeter excavations and the assumption is there that any pottery found is indeed residual from Roman levels on the site. An assemblage from the New Market Hall in Gloucester was found alongside a coin hoard dating later than 388 AD. The assemblage was claimed as being of 5th century date but is composed mainly of regionally-traded Romano-British wares such as Nene Valley colour-coated wares and shell-tempered wares from the south east midlands (Hassall and Rhodes 1974, 86-7). These wares were produced in areas of primary Anglo-Saxon settlement and there is no indication in the east midlands that they continued in use into the 5th century. At the latest, they might have continued in use to the middle of the century. The main arguments against the continuation of the Romano-British wheelthrown pottery industry are firstly, that the late Roman pottery industry depended on a monetary economy and inter-regional trade and that this economy was inextricably linked to taxation and the Empire. Secondly, none of the evidence presented so far stands up to close scrutiny. Nevertheless, Romanised pottery found on sites of 5thcentury and later date should never be assumed to be residual without proper study. Continuation/re-emergence of British handmade pottery tradition A phenomenon recognised in many parts of the British provinces is the re-emergence of pottery made without the use of the wheel in the later part of the Roman period. In the southeast this pottery is grog-tempered, in Yorkshire it is calcite-tempered and in Dorset it is sand-tempered black-burnished ware. Distinctive late BB1 forms and decorations have been identified which are probably of late 4th/early 5th century date. However, whereas in the early to mid 4th century BB1 is still found throughout Britain by the late 4th century its market area had shrunk and these late types are rare to absent in the West Midlands. The arguments for and against the survival of these handmade wares into sub-Roman times are similar to those for the wheelthrown wares and there is little evidence from this region for the emergence of a domestic or nonmarket-orientated handmade pottery industry in the late or sub-Roman period. A handful of handmade, burnished, limestone-tempered vessels from Gloucester have been proposed as belonging to this category but come from a site with a large amount of residual material and no further examples of this type have been found since (Darvill 1988). As with the wheelthrown pottery, however, the possibility of survival/re-emergence of a handmade pottery tradition in a post-Roman British/Welsh context cannot be dismissed. A 6th-century inhumation at the Roman fort of Binchester, in Co Durham, Page 2 of 19 West Midlands Regional Research Framework for Archaeology, Seminar 4: Vince 3 was accompanied by a crude handmade jar made in exactly the same manner as preRoman and ‘native’ Roman coarsewares. However, that pot was made in an area with both a strong pre-Roman pottery tradition and a less intense Roman presence than the West Midlands. Handmade, bonfire-fired pottery found on post-Roman sites in the West Midlands should not be assumed to be either residual Iron Age or, on the other hand, AngloSaxon in date and affiliation without close study. Importation of ceramics from the continent Sherds of imported amphorae, finewares and coarsewares (both greyware and a gritty whiteware) have been found and studied intensely in Wales and the Southwest of England for over half a century. Knowledge of the sources and dates of this pottery has increased over the years, thanks both to the scientific study of British finds and the stratigraphic excavation and study of pottery of 5th-century and later date from the Mediterranean (Radford and Thomas 1959, 1981, Peacock ?, Hodges ?, Fulford 1989). At various times, sherds from the West Midlands have been proposed as being of one of these imported groups (for example, at Much Wenlock). However, there are no confirmed finds from the region. Nevertheless, excavators of post-Roman sites in the region and their pottery specialists should be aware of the existence of these types and the likelihood that at least a few vessels of this type reached the region. The lack of finds from sites such as Cirencester (the provincial capital) and Wroxeter (a civitas capital) suggest that these wares remained close to their landing points rather than being traded or exchanged further inland, although an alternative interpretation would be that their main period of importation post-dated the decline of those sites. Introduction of Anglo-Saxon pottery traditions The pottery used by Anglo-Saxon settlers in eastern and southern England has clear antecedents in the traditional homelands of the Angles, Saxons and Jutes and a number of extremely close parallels between vessels from Anglo-Saxon and continental sites have been drawn. There is little doubt, therefore, that the earliest examples of these wares were made by potters who learnt their craft in Saxony, Jutland or elsewhere in northwest Europe. Several attempts to recognise a hybrid Romano-Saxon tradition, either through the adoption of Romano-British forms by Anglo-Saxon potters or the use of Anglo-Saxon traits on Roman or Sub-Roman pottery have been made but there is now little support for the concept and no convincing examples. Where pottery with Anglo-Saxon traits occurs in the West Midlands, therefore, it is in an Anglo-Saxon cultural context. Without DNA analysis it is not possible to say anything about the ethnic background of this pottery’s makers or users but the concentration of finds in the valleys of the Trent and the Warwickshire Avon is consistent with either the spread of Anglo-Saxon culture or actual folk movement along these valleys from the east. Several rules of thumb for the dating of decorated vessels have been proposed by Myres, and although many would now criticise both his early dating for the first Anglo-Saxon pottery and his attempts to marry stylistic development with stages in the colonisation of England there is agreement that there are genuine stylistic developments and that their sequence appears to hold true throughout the area of Anglo-Saxon settlement. This must imply a considerable degree of contact between Page 3 of 19 West Midlands Regional Research Framework for Archaeology, Seminar 4: Vince 4 different areas. There is less development in the coarseware pottery but even there the range of forms found shows no regional variation either from north to south or east to west. The only area where a regional patterning can be seen is in the use of chaff tempering. Organic matter is present in much Anglo-Saxon pottery either in the form of roots or rotting vegetation, suggesting that the potting clays were dug from subsoil or river banks rather than clay pits. However, fabrics in which the principal inclusion is chaff are much more common south of the Thames than they are in East Anglia, the East Midlands or north of the Humber. In the Thames basin the pottery sequence at Mucking suggests that chaff-tempering became more common with time (Hamerow 1987, 1987) and the same probably holds true for sites in the Thames valley in Oxfordshire (Vince 1989) whereas in Hampshire and Wiltshire chaff-tempering seems to be the main fabric tradition from the 6th century onwards. Despite earlier statements to the contrary, there is no evidence for chaff-tempering being a common tradition in the Anglo-Saxon homelands and where it is found on the continent it seems more likely to be evidence for Anglo-Saxon influence (Hamerow and others 1994). The incidence and frequency of chaff-tempering seems to have increased north of the Thames during the early to mid Anglo-Saxon periods. This general pattern is relevant to the Anglo-Saxon pottery found in the West Midlands, very little of which is tempered primarily with chaff except in the Warwickshire Avon. The latter area, therefore, shows signs of a closer link with the southeast than the Trent valley, as might be expected. Late 7th to mid 9th century ceramics Politically and socially there are major differences between the early Anglo-Saxon period (5th to 7th) and the mid Saxon period (7th to mid 9th centuries). The area was under Mercian hegemony and the border between Mercia and the Welsh was marked by the construction of Offa’s Dyke. Finally, the entire area was Christian, after a brief pagan interlude under the 7th-century Mercian kings. However, despite these changes, the archaeological evidence for the use of pottery is very similar. Low Pottery use It seems that in several areas of England which had been pottery-using in the early Anglo-Saxon period pottery ceased to be used, except in exceptional circumstances, in the mid Saxon period. Thus Continuation of 5th- to 7th-century handmade traditions Over much of southern and eastern England the domestic pottery of the mid Saxon period continued the traditions of the preceding period. The main change was the disappearance of the highly decorated pottery that had previously accompanied burials. Stamped vessels continued to be used on sites along the south coast (Cunliffe 1974, Timby 1988) but elsewhere typical mid Saxon assemblages consist of undecorated jars and bowls, with a high proportion of chaff-tempering. At Hatton Rock, in the Warwickshire Avon valley, all of the pottery contained abundant chafftempered, mixed with variably quantities of a coarse sandstone-rich sand. At Catholme, however, the settlement is thought to continue but there is no use of chafftempering at all. In neither area is there any major difference between the mid Saxon pottery and that of the 5th to 7th centuries. Page 4 of 19 West Midlands Regional Research Framework for Archaeology, Seminar 4: Vince 5 A sherd from a ring ditch at Sutton St Nicholas in Herefordshire may be an example of a ware tempered with Mountsorrel granodiorite (Williams and Vince 1997), lending support to the excavator’s identification of the ring ditch as a possible AngloSaxon barrow. Vessels with this granitic temper are found over a wide area of midland England and include sites in Warwickshire and Staffordshire. The interpretation of the inclusions is open to debate but it seems most likely that occurrences in the West Midlands were actually produced to the east and traded into the region. New handmade traditions In some parts of eastern England the transition to the mid Saxon period is marked in the pottery sequence by the introduction of new handmade pottery traditions. The best known of these is Ipswich ware, which a recent survey has concluded was the product of a single centre, at Ipswich. Despite this, the ware is found throughout East Anglia and along the east coast. It is also found on inland sites especially if those sites are on a navigable river or have a higher status than a simple agricultural settlement. No examples are known from the West Midlands although finds are known from Winchcombe, in Gloucestershire, and Repton, in Derbyshire, both mid Saxon monasteries with royal connections. In the southeast midlands Southern Maxey ware is found. This ware is tempered with a distinctive shell sand which includes fragments of punctate brachiopod shell. Again, no examples are known from the region although the distribution stretches from southern Lincolnshire, through Cambridgeshire and Northamptonshire into Bedfordshire. Finally, Northern Maxey ware is found mainly in central and northern Lincolnshire (Addyman and Whitwell 1970). Examples were traded to York (1993), Nottingham and Repton, all on navigable rivers. Although none of these wares has yet been found in the West Midlands it is quite likely that eventually examples will be found, for example at Droitwich or sites on the saltways leading east from there. Importation of ceramics from the continent As in the previous period, pottery was imported into the British Isles during the mid Saxon period. However, where as in the earlier period most of imports were traded along the western seaboard in this period they are almost exclusively found on sites close to the south or east coasts. There are no examples from the West Midlands and sherds initially identified as imports from the mill at Tamworth, Staffs, are now thought to be 11th- or 12th-century Stamford ware, stained black through burial in organic levels. This lack of imported wares, most of which appear to come from the middle Rhine, the Meuse valley and the Seine valley, is a reflection of the distance of the West Midlands from the east coast. However, it is possible that goods from the Bishop of Worcester’s estates were traded at Lundenwic, the emporium site situated on the Strand upriver of the City of London, and it would not therefore be impossible for such wares to have been used in the region. Late 9th to mid 11th-century ceramics The late 8th to mid 9th centuries had been marked in the British Isles by Viking raiding. How far the west midlands was affected by such raids is unknown, although Repton, just outside the region, was attacked in 874. This raid forced King Burgred of Mercia into exile and the Vikings set up Ceolwulf as a puppet king. In 877 they Page 5 of 19 West Midlands Regional Research Framework for Archaeology, Seminar 4: Vince 6 divided Mercia and occupied the northeastern part, leaving the west midlands in English Mercia, under Aethelred of Mercia and his wife Aethelflaeda. In the Danelaw this period saw the foundation and growth of towns such as Lincoln, Stamford, Torksey, Nottingham, Leicester, Northampton and Derby. A feature of all of these towns was the existence of a pottery industry. In the case of Torksey, pottery making is practically the only archaeological evidence for the Anglo-Scandinavian town whereas in some other towns, such as Leicester or Nottingham, it seems that the pottery industry was never very large and the inhabitants of the town relied for the most part on pottery made elsewhere. It is clear from intensive fieldwork in some of these towns that they varied considerably in size and character although Torksey is the only one which might not have been defended. The situation in English Mercia is as yet difficult to compare, primarily because it has proved difficult to date late Saxon levels in towns such as Hereford, Shrewsbury, Stafford or Worcester with the precision needed to compare their size and nature before and after the mid 10th century, when the Danelaw was reconquered by the English. Pottery use Although there is evidence for late 9th to mid 11th-century pottery in each of the counties of the West Midlands, almost all of these finds come from defended sites, which may or may not have been towns at this time. Even where pottery is found on rural sites it is in such small quantities that it suggests that pottery was hardly used (or that the areas occupied in the pre-conquest period have not been found). If the region was only tentatively using pottery at this time then it contrasts strongly with the situation to the south, where pottery of late 10th/early 11th century date is now turning up frequently on rural excavations, as well as with the situation immediately to the east, in Northamptonshire. Nottinghamshire, Derbyshire and Cheshire, however, still have few finds of late 9th to 11th century pottery outside of the urban centres and it may be that the West Midlands and these counties have a similar use of pottery at this time. Alternatively, it is quite likely that the appropriate rural sites still await discovery. Intensive field walking in Worcestershire by Chris Dyer, at Pendock and Hanbury for example, does, however, confirm that pottery of pre-conquest date is much less common than in the immediately post-conquest period. Continuation of 7th to 9th-century handmade traditions Excavations at 1 Westgate Street, Gloucester, revealed a waster pit of late Saxon date containing handmade, limestone-tempered pottery (Heighway and others 1979) and sherds of this pottery have been found on several sites in Hereford (Vince 1985a, Vince 2002).Alongside this handmade pottery were sherds of wheelthrown, lid-seated jars made in exactly the same fabric. The handmade jars have distinctive everted rims, added as a coil to the inside of the shoulder of the pot and giving rise to a very thick neck. No examples of this type are known in the area in the mid Saxon period (the area around Gloucester seems to have been aceramic, whilst immediately to the south and east chaff-tempered pottery was used). However, the same technique was used in east Wiltshire and Hampshire (as at Hamwic,Timby 1988) and it is likely that the potter learnt to pot in that region. The wheelthrown, lid-seated vessels, however, also have no local antecedents but are found in the east Midlands in several industries. This suggests that perhaps these towns attracted artisans from different areas, perhaps leading to the exchange of ideas and the emergence of new traditions. Page 6 of 19 West Midlands Regional Research Framework for Archaeology, Seminar 4: Vince 7 Introduction of wheelthrown pottery traditions By the end of the 10th century a network of potteries producing wheelthrown, kilnfired and occasionally glazed wares supplied much of England, including the West Midlands, with pottery. The earliest dated examples occur in the late 9th century, at York (1990) and Lincoln (forthcoming), and it seems fairly certain that the introduction of this craft was associated with the Viking settlement of the Danelaw. There is evidence from London for the use of a similar wheelthrown ware in the early 10th century but, as at Gloucester, handmade vessels were produced alongside wheelthrown ones (Vince and Jenner 1991). Only one wheelthrown pottery is known to have been made in the West Midlands region, at Stafford, but examples of wheelthrown wares made outside the region, to the south and east, are known from Hereford (Vince 1985a, Fabrics D1, E1, G2a), Shrewsbury and Worcester (Carver 1980). Stafford-type ware is tempered with a rounded quartz sand which in thin section is similar to the fluvio-glacial sands which cover much of the region, extending into the Cheshire Plain to the north and the lower Severn Valley to the south. At present, therefore, the attribution to Stafford is based on petrological similarity, and the typology of vessels. Further work is currently in progress, however, as part of the post-excavation and publication of the Stafford kiln sites, excavated in the 1970s. This work may finally allow us to positively identify Stafford-type ware wherever it is found. The most recent distribution map is that of Rutter (Rutter 1985, see also Vince 1985b) in both of which it is assumed that the ware initially called Chester ware is actually produced at Stafford. A handful of sherds of glazed ware from sites in Hereford have been identified tentatively as local products on the basis of their silty, micaceous red-firing fabric. The range of forms suggests that the vessels were spouted pitchers with strap handles and sagging bases, similar to those produced at Stamford. An example of this ware was found at Winchcombe, in Gloucestershire, and there are possible examples from Gloucester itself but with these exceptions the ware is only known from Hereford, which is the most likely production site. Similar silty, micaceous fabrics were produced over an extensive area of the Welsh Marches in the medieval period. At Hereford there are two phases of late Saxon pottery use. In the first, dated to the late 10th/early 11th century, Stafford-type ware was used on its own (with the exception of a single red-painted pitcher, identified as a late 9th-century red-painted Stamford ware, Hereford E2a Kilmurry 1977). In the second phase sherds of Gloucester products and glazed and unglazed Stamford ware were found. There is also a single sherd of St Neot’s type ware (Hereford G2a). This phase has been dated to the early to mid 11th century. The Hereford late Saxon pottery sequence seems to come to an abrupt halt in the middle of the 11th century. This hiatus has been associated with the Welsh raid on the town in 1055. In subsequent levels it is likely that the little Stafford-type ware found is residual. At Berrington Street, Site 4, however, a sequence of floor levels in a ground-level timber building fronting onto the street seems to pass without a break from assemblages with only Stafford-type ware, to those with Stamford and Gloucester wares to those containing only later 11thcentury Vale of Gloucester wares (Hereford D2, see below). This would suggest that we should not over-emphasise the effect of this Welsh raid and that the change in pottery sources may have some other explanation. Page 7 of 19 West Midlands Regional Research Framework for Archaeology, Seminar 4: Vince 8 The medieval pottery tradition The post-conquest pottery tradition in the West Midlands, as in much of southern England, consists mainly of handmade, squat cooking pots, with sagging bases, with a few other handmade forms: notably bowls and spouted pitchers. The range of forms is not vastly different from that found in the preceding period but there is clearly no attempt to copy those forms in any detail. Furthermore, decoration, where present, consists of individual stamps, combed lines and some single line grooving. None of these decorative techniques is found on earlier late Saxon pottery, either handmade or wheelthrown. In some parts of the region these types first occur after the Norman conquest, in some they occur first at about the time of the conquest and in others they pre-date the conquest. This diachronic introduction has two implications, the first practical and the second interpretative. Firstly, it is not possible to use the introduction of this tradition as an independent dating marker. Secondly, the sudden and disruptive change in pottery manufacture cannot be a consequence of the Norman conquest. Gerald Dunning had already come to this conclusion by 1959 where he called the general tradition to which these vessels belong “Early Medieval” (Dunning 1959). The preconquest date was confirmed in the 1980s in the City of London through the discovery of early medieval pottery in deposits excavated at the Billingsgate Lorry Park, dated to c.1039-40. Pottery assemblages from other dendrochronologicallydated deposits from the Thames waterfront show that early medieval pottery was introduced in the late 10th or early 11th centuries, replacing wheelthrown London Late Saxon Shelly ware (Vince and Jenner 1991). The earliest examples of early medieval pottery in the West Midlands come from Hereford and Worcester (Vince 1985a, Fabrics B1, C1 and D2;Carver 1980). In both cases, the majority of these vessels were made from limestone-tempered fabrics, probably from the same source. In the Domesday inquest potters are recorded at Haresfield, south of Gloucester, and although fieldwork in the parish has, so far, failed to find any evidence for production all the pottery of this period found in the area is of exactly the same fabric type (Gloucester TF41b, Hereford Fabric D2). At Gloucester, the earliest examples of this ware are globular-bodied, vessels with short everted rims. These occurred in rubbish pits which predated the first, timber castle (Darvill 1988, Hurst 1984). Assemblages containing mainly vessels of this type have been found at Hereford and Friar Street, Droitwich. Soon after, and certainly before 1100, these everted-rimmed vessels had been joined by straight-walled, club-rimmed vessels. An example of this type has been found at Stafford Castle and numerous examples were found at Hereford cathedral, in a deposit probably dating to the very early 12th century. Late 11th/early 12th-century assemblages such as this also contain small quantities of pottery with angular Malvernian rock inclusions (Hereford Fabric B1, Gloucester TF40) and jars with a rounded quartz sand temper and everted, flat-topped rims (Hereford Fabric C1, Gloucester .TF42). The latter are identical in form and fabric to those found in Worcester, where pottery production is documented from the late 12th century. Sherds of these two Worcestershire wares occur on many sites in the West Midlands, including rural sites in Herefordshire and sites in Shropshire as well as in Worcestershire and it seems that the widespread use of pottery in the region can be dated to this late 11th/early 12th-century period, after the Norman conquest. Page 8 of 19 West Midlands Regional Research Framework for Archaeology, Seminar 4: Vince 9 Research Aims In the following list I have itemised what I consider to be the major research issues in the study of pottery in the West Midlands in the 5 th to 11th centuries. These issues are over and above the general construction and elaboration of the ceramic fabric and form sequence which is a necessary pre-requisite for any research. 5th to 7th centuries Test the nature of the boundary to pottery-use Was there a sharp boundary, on one side of which people were using pottery in everyday domestic contexts and on the other they were hardly using pottery at all? Date the earliest Anglo-Saxon pottery in the Trent and Warwickshire Avon valleys If Anglo-Saxon settlement or acculturation reached these parts of the country in the 6th century then was pottery used in the intervening post-Roman, pre-Anglo-Saxon period? Use organic chemical analysis to study pottery function Was there any correlation between pottery form and function? Were decorated pots used for different purposes, or were they made solely for display? Chararacterise pottery and study distribution patterns of fabrics Can we find any evidence for domestic production in the early Anglo-Saxon period or was pottery-making always a specialised craft? late 7th to mid 9th centuries Is there an increase in the area of pottery use? Or even a decline in the use of pottery, as seems to be the case in Oxfordshire. Are non-local wares present? Are Ipswich ware, Maxey wares and continental imports really absent from the West Midlands, or just not recognised? Late 9th to mid 11th centuries The source(s) and chronology of Stafford-type ware, including the start and end dates of the industry There are at present two very different chronologies put forward for the inception of Stafford-type ware. At one extreme, it is said to be 8th/9th century or later and at the other it is said to be late 10th. The source of Hereford A7a glazed ware Although the fabric of this glazed ware is visually and petrologically identical to later, locally-made wares, the Hereford A7a glazed ware industry is anomalous, in that Page 9 of 19 West Midlands Regional Research Framework for Archaeology, Seminar 4: Vince 10 there is no evidence for the production of unglazed coarsewares. Confirmation of a local source, ideally through the discovery of wasters but otherwise through chemical analysis of the clay, is required. The source of the Hereford red-painted pitcher. This has a bearing on the chronology of the city’s pottery sequence This single vessel was dated by Dr Kilmurry to the late 9th century but sherds were found in association with Stafford-type ware in layers overlying the town’s intramural cobbled street. This has been interpreted as being due to the sherds having originally been incorporated into the Alfredian rampart. If so, it would imply that there was a movement of pottery from the Danelaw to the West Midlands at a time when the two regions were in conflict. Alternatively, the vessel might be of northern French origin and later in date. Thin section evidence was equivocal but it is now possible to distinguish these two wares chemically. Medieval tradition Characterisation of the West Midlands medieval ceramic tradition: wares, fabrics, typologies At present there is only a rough framework for the early medieval pottery traditions of Warwickshire, Staffordshire and Shropshire. Establishment of the starting date of these industries Did the introduction of early medieval pottery spread from southeast to northwest, as appears to be the case in Herefordshire and Worcestershire, or from several foci? The origins of the traditions Assuming that the early medieval pottery industries arose through outside influence, such as the immigration of potters, can we chart this process in detail through comparison of West Midlands and neighbouring pottery? Were there any locally-made handmade glazed wares in the West Midlands in the mid 11th-century? In parts of the country, for example Nottinghamshire, Hampshire, and the Thames basin, there is a suggestion that there was handmade glazed ware in use before the Norman conquest. Is there any evidence for this in the West Midlands? Bibliography Addyman, P. V. and Whitwell, J. B. (1970) "Some Middle Saxon Pottery Types in Lincolnshire." Antiq J, 50, 96-102. Alcock, L (1963) Dinas Powys Cardiff. Page 10 of 19 West Midlands Regional Research Framework for Archaeology, Seminar 4: Vince Carver, M. O. H. (1980) 11 "The Excavation of Three Craftsmens Tenements in Sidbury, Worcester, 1976." Trans Worcestershire Archaeol Soc, 3rd ser, 7. Cunliffe, B. W. (1974) "Some late Saxon stamped pottery from southern England." in V. I. H. H. Evison and J. G. Hurst, eds., Medieval Pottery from Excavations: Studies presented to Gerald Clough Dunning, with a bibliography of his works, John Baker, London, 127-36. Darvill, T. (1988) "Excavations on the Site of the Early Norman Castle at Gloucester 1983-84." Medieval Archaeol, XXXII, 1-49 Dunning, G. C. (1959) "Pottery of the Late Anglo-Saxon Period in England." Medieval Archaeol, III, 31-78. Fulford, M. (1989) "Byzantium and Britain: a Mediterranean Perspective on PostRoman Mediterranean Imports in Western Britain and Ireland." Medieval Archaeol, XXXIII, 1-6. Hamerow, H (1987) The pottery and spatial development of the Anglo-Saxon settlement at Mucking, Essex. Unpub D.Phil Thesis, University of Oxford. Hamerow, H., Hollevoet, Y., and Vince, A. (1994) "Migration Period Settlements and 'Anglo-Saxon' Pottery from Flanders." Medieval Archaeology, XXXVIII, 1-18. Hamerow, H. F. (1987) "Anglo-Saxon Settlement Pottery and Spatial Development at Mucking, Essex." Berichten van de Rijksdienst voor het Oudheidkundig Bodemonderzoek, 245-73. Page 11 of 19 West Midlands Regional Research Framework for Archaeology, Seminar 4: Vince 12 Hassall, M. and Rhodes, J. (1974) "Excavations at the new Market Hall, Gloucester, 1966-7." Transactions of the Bristol and Gloucestershire Archaeological Society, XCIII, 15-100. Heighway, C. M., Garrod, A. P., and Vince, A. G. (1979) "Excavations at 1 Westgate Street, Gloucester, 1975." Medieval Archaeol, XXIII, 159-213. Hodges, R. A. (?) "The date and source of E Ware." ?, 39-41. Hurst, H. (1984) "The Archaeology of Gloucester Castle: An Introduction." Trans Bristol Gloucestershire Archaeol Soc, 102, 73-128. Kilmurry, K. (1977) "The production of red-painted pottery at Stamford, Lincs." Medieval Archaeol, XXI, 180-6. Mainman, A J (1990) Anglo-Scandinavian Pottery from 16-22 Coppergate. The Archaeology of York 16/5 London, Council British Archaeol. Mainman, A J (1993) The pottery from 46-54 Fishergate. The Archaeology of York 16/6 London, Council British Archaeol. Peacock, D. P. S. (?) "E Ware and Aquitaine." ?, 38-9. Radford, C. A. R. and Thomas, C. (1959) "Imported Pottery in Dark Age Western Britain." Medieval Archaeol, III, 89-112. Rutter, J. A. A. (1985) "The Pottery." in D. J. P. Mason, ed., Excavations at Chester: 26-42 Lower Bridge Street 1974-6. The Dark Age and Saxon Periods, Grosvenor Museum Archaeol Excav Survey Rep 3 Chester City Council: Page 12 of 19 West Midlands Regional Research Framework for Archaeology, Seminar 4: Vince 13 Grosvenor Museum, Chester, 40-61. Thomas, C (1981) A Provisional List of Imported Pottery in post-Roman Western Britain and Ireland. Inst Cornish Stud Spec Rep 7 Redruth, Inst Cornish Stud. Timby, J. R. (1988) "The Middle Saxon pottery." in P. Andrews, ed., Southampton Finds, Vol 1: The Coins and Pottery from Hamwic, 73-124. Vince, A. G. (1985a) "Part 2: the ceramic finds." in R. Shoesmith, ed., Hereford City Excavations: Volume 3. The Finds, CBA Research Report 56 The Council for British Archaeology, London. Vince, A. G. (1985b) "The Saxon and Medieval Pottery of London: A Review." Medieval Archaeol, XXIX, 25-93. Vince, A. G. and Jenner, M. A. (1991) "The Saxon and Early Medieval Pottery of London." in A. G. Vince, ed., Aspects of Saxo-Norman London: 2, Finds and Environmental Evidence, London Middlesex Archaeol Soc Spec Pap 12 London Middlesex Archaeol Soc, London, 19-119. Vince, A. (1989) "Chapter 7: The Petrography of Saxon and early medieval pottery in the Thames valley." in J. Henderson, ed., Scientific Analysis in Archaeology, Oxford University Committee for Archaeology Monograph 19 Oxford University of Committee for Archaeol & UCLA Institute of Archaeol, Oxford and Los Angeles, 163-77. Vince, A. (2002) "The Pottery." in A. Thomas and A. Boucher, eds., Hereford City Excavations Volume 4: Further Sites & Evolving Interpretations, Logaston Press, Logaston, 65-92. Page 13 of 19 West Midlands Regional Research Framework for Archaeology, Seminar 4: Vince 14 Williams, D. and Vince, A. (1997) "The Characterization and Interpretation of Early to Middle Saxon Granitic Tempered Pottery in England ." Medieval Archaeol, XLI, 214-219. Young, Jane and Vince, Alan (forthcoming) A Corpus of Anglo-Saxon and Medieval Pottery from Lincoln. Lincoln Archaeological Reports Oxford, Oxbow. Page 14 of 19 West Midlands Regional Research Framework for Archaeology, Seminar 4: Vince 15 Appendix One locality site name site recorder organisation finds location Details Hereford 2 Castle Street R Shoesmith City of Hereford Archaeology Unit Hereford City Museum Late Saxon Hereford 20 Church Street R Shoesmith City of Hereford Archaeology Committee Hereford City Museum Late Saxon Hereford 20 Church Street R Stone Knight M City of Hereford Archaeology Committee Hereford City Museum Late Saxon Hereford 28-29 Commercial Street J Sawle (Black and White Cafe) City of Hereford Archaeology Committee Hereford City Museum Late Saxon Hereford Bewell Square R Shoesmith City of Hereford Archaeology Committee Hereford City Museum Late Saxon Hereford Bishop's Palace R Shoesmith City of Hereford Archaeology Committee Hereford City Museum Late Saxon Hereford Bus Cinema/County Guthlac's Priory Station/The R Shoesmith Gaol/St City of Hereford Archaeology Committee Hereford City Museum Late Saxon Hereford Castle Green R Stone Knight Hereford Deens Court Hereford Herefordshire & Hereford City Museum Late Saxon R Shoesmith City of Hereford Archaeology Committee Hereford City Museum Late Saxon Drybridge House R Shoesmith City of Hereford Archaeology Committee Hereford City Museum Late Saxon Hereford East Street 1997 R Shoesmith City of Hereford Archaeology Unit Hereford City Museum Late Saxon Hereford Mappa Mundi Stone, Richard & City of Hereford Archaeology Unit Appleton-Fox, Nic Hereford City Museum Late Saxon Page 15 of 19 & M City of Hereford Archaeology Unit West Midlands Regional Research Framework for Archaeology, Seminar 4: Vince locality site name Hereford Maylord Orchard Shopping R Shoesmith Centre City of Hereford Archaeology Committee Hereford City Museum Late Saxon Hereford Maylord Street R Shoesmith City of Hereford Archaeology Committee Hereford City Museum Late Saxon Hereford Tesco's J Sawle of Hereford Archaeology Committee Hereford City Museum Late Saxon Hereford Tesco's R Shoesmith City of Hereford Archaeology Committee Hereford City Museum Late Saxon Hereford Trinity Almshouses J Sawle Hereford and Worcester County Council Hereford City Museum Late Saxon Hereford Wall Street R Shoesmith City of Hereford Archaeology Committee Hereford City Museum Late Saxon Hereford Wall Street (Trench A) J Sawle City of Hereford Archaeology Committee Hereford City Museum Late Saxon Hereford Wye Street R Shoesmith City of Hereford Archaeology Committee Hereford City Museum Late Saxon Ray, Keith Herefordshire Council early to mid Saxon S Losco-Bradley TVARC Sutton Nicholas St site recorder 16 organisation finds location Details Staffordshire Barton-under- Catholme Needwood City of Stoke on Trent early to Museum mid Saxon Maer Berth Hill Stafford Clarke Street M. O. H. Carver Stoke on Trent Museum Late Saxon Stafford Eastgate Street M. O. H. Carver Stoke on Trent Museum Late Saxon Stapenhill Page 16 of 19 Stoke on Trent Museum early to mid Saxon Bass Museum - Burton Early on Trent/Stoke on Trent AngloSaxon West Midlands Regional Research Framework for Archaeology, Seminar 4: Vince site recorder organisation 17 locality site name finds location Details Wolseley Bridge 'near Wolesley Bridge' Stoke on Trent Museum Early AngloSaxon Wychnor AS cemetery Bass Museum - Burton Early on Trent/Stoke on Trent AngloSaxon Alveston AS cemetery Stratford-upon-Avon Museum Early AngloSaxon Baginton AS cemetery Private Early AngloSaxon Baginton AS cemetery Stratford-upon-Avon Museum Early AngloSaxon Baginton AS cemetery Coventry Museum Early AngloSaxon Bidford-onAvon AS cemetery Stratford-upon-Avon Museum Early AngloSaxon Bidford-onAvon AS cemetery Worcester Museum Early Anglo- Warwickshire Page 17 of 19 West Midlands Regional Research Framework for Archaeology, Seminar 4: Vince locality site name site recorder organisation 18 finds location Details Saxon Burton Dassett AS cemetery Warwick Museum Early AngloSaxon Long Itchington AS cemetery Warwick Museum Early AngloSaxon Marton AS cemetery Warwick Museum Early AngloSaxon Southam early to mid Saxon Worcestershire Beckford Beckford B Saxon Cemetery Fladbury Fladbury Birmingham Museum D. P. S. Peacock D. P. S. Peacock Kidderminster Signet Fields, Bromsgrove Road, Wodecote Green Pershore Pershore Page 18 of 19 City Early AngloSaxon early to mid Saxon early to mid Saxon Unknown (recorded by G early to Dunning) mid Saxon Pershore P. Whitehead early to West Midlands Regional Research Framework for Archaeology, Seminar 4: Vince locality site name Pershore Wychavon Central Development Phase II Page 19 of 19 site recorder organisation 19 finds location Details mid Saxon early to mid Saxon