vowel foreign

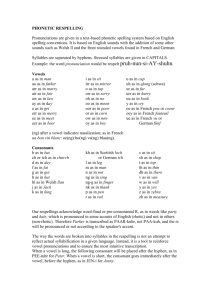

advertisement

CONFLUENCE 26 February 2011 Receptive Skills and English Language: Problem of Vowel Sounds Dr. M. S. Wankhede Department of English Dhanwate National College, Nagpur. Abstract: Acquiring a language is the mastering of four basic language skills viz. listening, speaking, reading and writing; of which listening and reading are receptive or passive skills and they contrast with the productive or active skills – speaking and writing. In India English is taught as a second or foreign language and learners receive and understand the former two skills, hence they are receptive skills. In the second language acquisition learners have to face the hindrance of their mother tongue and the way of mastering the basic language skills of English poses great difficulty for the Indian learners as their organs of speech have been set for their mother tongue and molding them in the new style or pattern is not that much easy. Second language acquisition is more difficult for the learners than learning “the language of their parents and community in a monolingual setting” (Ng Bee Chin, 2007:40) for, the first language acquisition begins at a ‘relatively young age’ as compared to the second language acquisition. Language plays significant role in communication and “communication and language are very closely related but they are not the same phenomenon” (William Littlewood, 1992:09). Language is not just a means of communication but “has an important mental functions and affects how we understand and reflect on the world around us” (ibid.). Non-linguistic communication like ‘barking of dogs’ ‘crying of a child’ or ‘street light’ etc. is also possible but they have their own limitations. It is a language only through which most complicated emotions, passions, feelings are properly communicated. Language is made up of Vowels and Consonants. Vowels form the ‘nucleus’ and Consonants the ‘onset.’ RP (Received Pronunciation) system has suggested 5 long vowels, 7 short vowels and 8 diphthongs; and 6 plosives, 2 affricates 9 fricatives, 3 nasals, 1 lateral and 3 approximants; thus in all there are 20 Vowel sounds and 24 Consonant sounds making together 44 sounds (Daniel Jones, 1993:xii). The detailed descriptions and interpretations of all the Vowel sounds will be taken in the full text. Indian learners find much difficulty with the Vowel sounds and not with the Consonant sounds. In traditional manner we are taught and have accepted only 5 Vowel sounds – a, e, i, o, u – but on functional basis there are 20 Vowel sounds. English, being a window on the world and a library language, Indians need to master it for the practical purposes. We may oppose the literature of England but ought to master English, which is the medium of instructions in higher education beside the language of medical sciences, life sciences, economics and information technology. The present paper intends to focus on mastering Vowel sounds. Introduction: ISSN: 2250-138X Page 268 CONFLUENCE 26 February 2011 Acquiring a language is the mastering of four basic language skills viz. listening, speaking, reading and writing; of which listening and reading are receptive or passive skills and they contrast with the productive or active skills – speaking and writing. In India English is taught as a second or foreign language and learners receive and understand the former two skills, hence they are receptive skills. In the second language acquisition learners have to face the hindrance of their mother tongue and the way of mastering the basic language skills of English poses great difficulty for the Indian learners as their organs of speech have been set for their mother tongue and molding them in the new style or pattern is not that much easy. English, being a window on the world and a library language, Indians need to master it for the practical purposes. We may oppose the literature of England but ought to master English, which is the medium of instructions in higher education beside the language of medical sciences, life sciences, economics and information technology. The present paper intends to focus on mastering Vowel sounds. Second language acquisition is more difficult for the learners than learning “the language of their parents and community in a monolingual setting” (Ng Bee Chin, 2007:40) for, the first language acquisition begins at a ‘relatively young age’ as compared to the second language acquisition. Language plays significant role in communication and “communication and language are very closely related but they are not the same phenomenon” (William Littlewood, 1992:09). Language is not just a means of communication but “has an important mental functions and affects how we understand and reflect on the world around us” (ibid.). Non-linguistic communications like ‘barking of dogs’ ‘crying of a child’ or ‘street light’ etc. is also possible but they have their own limitations. It is a language only through which most complicated emotions, passions, feelings are properly communicated. This is true in case of all the languages spoken on all parts of globe, having script or not, and not any particular language. It has been pointed out by Robin Barrow that “…teaching English, whether to ethnic minorities in English-speaking countries, stands in little need of justification (1990:03).” This statement shows the importance of English language. He further remarks: The ability to speak the language of the country in which one lives has obvious value; but English is also useful for those whose mother tongue it is not, given that it is the second most widely used language in the world. It has an unsurpassed richness in terms of vocabulary, and hence in its scope for giving precise and detailed understanding of the world. (Ibid.) Here once again it is apparent that English has been widely acclaimed as important language. It is crystal clear that the native language that is mother tongue is also very important but if we want to have the wider knowledge and intimacy with the whole world, no one, I hope, would deny the fact that English is the only language which can be of utmost requirement as the whole world is today being globalize and is becoming a ‘global village’; not that it is also important for our international affairs. Orientals may oppose the literature of England but they have to accept the importance of English as language otherwise we could be isolated and broken from the world affairs resulting in the greatest loss for the country in the sphere of development and progress. The role of English teacher in the classroom plays a significant role because it is, as Michael Byram puts, s/he who is “concerned with teaching the skills of ‘communicative performance’ and assessing those skills in terms of ‘communicative behaviour’. In its fullest and richest meaning ISSN: 2250-138X Page 269 CONFLUENCE 26 February 2011 communicative competence as opposed to performance includes the notions of insight and positive attitudes ...” (1990:86). While explaining the importance of English teacher in the classroom Martin Cortazzi asks the following sorts of questions: Who speaks most of the time? Who asks most of the questions? Who evaluates the answers to the questions? Who has the right to interpret others? Who says, whether, when and how others may speak? Who controls the language of interaction? Who says what has been learnt, how well and why? (1990:58) He answers all these questions by saying “the teacher” which makes us understand the role of English teacher is of great importance. Language is not just simply a means of communication but something more than that. Robert Lado opines: “Language is intimately tied to man’s feelings and activity. It is bound up with nationality, religion, and feeling of self. It is used for work, worship, and play by everyone, be he beggar or banker, savage or civilized” (1986:11). The teacher of English has to use “scientific” approach. A scientific approach to language teaching uses scientific information; it is based on theory and a set of principles which are internally consistent. It measures results. It is impersonal, so that it can be discussed on objective evidence. And it is open, permitting cumulative improvement on the basis of new facts and experience (Robert Lado, 1986:49). Lado (1986:49) has suggested 17 principles of language teaching, they are as follows: 1. Speech before writing, 2. Basic sentences, 3. Patterns as habits, 4. Sound system for use, 5. Vocabulary control, 6. Teaching the problems, 7. Writing as representation of speech, 8. Graded patterns, 9. Language practice versus translation, 10. Authentic language standards, 11. Practice, 12. Shaping of responses, 13. Speed and style, 14. Immediate reinforcement, 15. Attitude toward target culture, 16. Content and 17. Learning as the crucial outcome. As the present paper is concerned with the Vowel sounds in English it is not required to explain and go through all the principles stated here. But the first principle ‘Speech before writing’ is of great ISSN: 2250-138X Page 270 CONFLUENCE 26 February 2011 importance here. The teachers of English should teach his/her students listening and speaking first, which has been neglected in most of the school curriculum and only the attention is paid to reading and writing, which is second step, for, “language is most completely expressed in speech. Writing does not represent intonation, rhythm, stress, and juncture” (1986:50). The learners should be taught to “memorize basic conversational sentences as accurately as possible (Ibid.)” which is the second principle suggested by Lado. The learning a language is the formation of habits. The teachers should teach their students to “establish patterns as habits through pattern practice” (1986:51) because “knowing words, individual sentences, and/ or rules of grammar does not constitute knowing the language. Talking about the language is not knowing it” (1986:51). Thus we find that ‘knowing a language’ is different from ‘knowing about a language.’ It is the need of English language teachers to teach their students “the sound system structurally for use by demonstration, imitation, props, contrast, and practice” (Ibid.). Writing should be taught as representation of speech so that the mistakes should be avoided. Mostly in Indian school curriculum language practice is put at bay and translation has been used in most of the English classrooms. Authentic language standard has to be taught. Language should be taught “as it is and not as it ought to be” (1986:54). Language is made up of Vowels and Consonants. Vowels form the ‘nucleus’ and Consonants the ‘onset.’ RP (Received Pronunciation) system has suggested 5 long vowels, 7 short vowels and 8 diphthongs; and 6 plosives, 2 affricates 9 fricatives, 3 nasals, 1 lateral and 3 approximants; thus in all there are 20 Vowel sounds and 24 Consonant sounds making together 44 sounds (Daniel Jones, 1993:xii). The detailed descriptions and interpretations of all the Vowel sounds will be taken in the full text. Indian learners find much difficulty with the Vowel sounds and not with the Consonant sounds. In traditional manner we are taught and have accepted only 5 Vowel sounds – a, e, i, o, u – but on functional basis there are 20 Vowel sounds. For the production of speech sounds “the active articulators” and “passive articulators” are used. “The active articulators are the lower lip and the tongue; these are the articulators that make contacts with the passive articulators. The passive articulators are the upper lip, the upper teeth, the roof of the mouth (divisible for the sake of convenience into the teeth-ridge, the hard-palate and the soft-palate), and the back wall of the throat of pharynx” (Dr. Radhey L Varshney, 2007-08:41). For the ideal description of speech sounds, we ought to have information related to production, transmission and reception. In other words it can be cited what Varshney has pointed. According to him the ideal description of speech sounds “should describe a sound in terms of the movements of the organs of speech, the nature of the sound which is produced and the features perceived by a listener” (2007-08:42). For the better communication, all the three stages – production, transmission and reception – are of great importance. In addition to phonetic, phonological or orthographic references, the classification of speech sounds into consonants and vowels is usual. Kenneth Pike divides the speech sounds into vocoids (vowel sounds), contoids (consonant sounds) and semi-vocoids or semi-contoids (for example /w/ and /j/ in English) (Dr. Radhey L Varshney, 2007-08:45). The area of the present paper is concerned with the vowel sounds and hence consonant sounds are not taken into consideration. Moreover it is the vowel sounds that trouble much to the Indian learners as compared to the consonant sounds. Vowel sounds are generally classified on the height of the tongue (high, mid, low or close, half-open and open); advancement of tongue (front, central, back); and lip-rounding (rounded and un-rounded) (Dr. Radhey L Varshney, 2007-08:54). ISSN: 2250-138X Page 271 CONFLUENCE 26 February 2011 As has already been narrated English teachers in India teach the learners only five vowel sounds (a, e, i, o, u) in fact there are twelve pure vowels (monophthogs) and eight impure vowels (diphthongs) which are also called as gliding vowels as they unlike pure vowels or monophthongs continually go on changing in their quality. “A vowel sound that glides form one quality to another is called a diphthong, and a vowel sound that glides successively through three qualities is triphthong” (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Vowel). The vowel sound in English word hit is a monophthong /I/, the vowel sound in the English word boy is a diphthong / ɔɪ / and the vowel sounds in the English word flower /aʊər/, are called as triphthong (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Vowel). In English, we have four front vowels: /ɪI, i:, e, æ/; five back vowels / ɑ:, ɒ, ɔ:, ʊ, u:/; and three central vowels / ə, ɜ:ʳ, ʌ/ making them twelve in number as pure vowels which occur in English words /sit, seat, set, sat, cart, cot, caught, book, tool, about, earth and but/ respectively (symbols are copied and modified from /www.antimoon.com/how/pronunc-soundsipa.htm/). All vowels are voiced and there are five long vowels and seven short vowels ‘Long’ vowels are comparatively longer than the ‘short’ vowels. Diphthongs are all long vowels (J. Sethi & P. V. Dhamija, 2000:65). There are eight diphthongs in English of which (i) three / eɪ, aɪ, ɔɪ/ glide towards /ɪ/; (ii) two / aʊ, əʊ/ towards /ʊ/ and (iii) three /ɪəʳ, eəʳ, ʊəʳ / towards /ə/. The diphthongs grouped under (i) and (ii) glide towards closer position, and those under (iii) towards the central position. Therefore the diphthongs under groups (i) and (ii) are called as closing diphthongs and under (iii) as centring diphthongs (J. Sethi & P. V. Dhamija, 2000:77). J. Sethi and P. V. Dhamija have illustrated, RP (Received Pronunciations) twenty vowel sounds (12 monopthongs and 8 diphthongs) according to their occurrence in the initial, medial and final positions as under (examples are taken from the book cited above (2000:64,65) and symbols from www.antimoon.com/how/pronunc-soundsipa.htm): Vowel Initial Medial Final i: ɪ e æ ɑ: ɒ ɔ: ʊ u: ʌ east it end and arm on all key duty ooze up seen hit lend land harm cot caught put choose cup ɜ:ʳ ə earn ago turn police sir tailor eight straight stray Monophthongs car saw shoe Diphthongs: eɪ ISSN: 2250-138X Page 272 CONFLUENCE 26 February 2011 əʊ aɪ aʊ ɔɪ oak ice out oil joke mice shout boil slow my how boy ɪəʳ ear beard clear eəʳ ʊəʳ air shared cured care poor (Every blank space in the illustration shows the non-occurrence of vowel in that position). Illustration of the Vowel sounds (J. Sethi & P. V. Dhamija, 2000:66-88): Front Vowels: / i:/ as in seat, /ɪ/ as in sit, /e/ as in set, /æ/ as in sat. / i:/ In the production of this sound the front part of the tongue is raised to a height just below the close position; the lips are spread; and the tongue is tense. It is a long vowel and can be labeled as a front close un-rounded vowel. This vowel occurs for the spelling ay (quay); e (be, these, even, Eden, Peter); ea (beat, each, lead, sea, tea); ee (eel, seed, keep, free, nee); ei (receive, deceive, conceive, seize); eo (people); ey (key); i (machine, police, prestige, ski); ie (relief, piece, field, siege). This vowel occurs in all the three positions – initial, medial and final but it does not occur before the consonant / ŋ /. It occurs more frequently in accented than in unaccented positions. /ɪ/ In the production of this vowel sound the rear part of the front of the tongue is raised just below the halfclose position; the lips are loosely spread and the tongue is lax. It is a short vowel and can be labeled as a. centralized front half-close un-rounded vowel. This vowel occurs for the spelling a (village, private, baggage, surface); ai (bargain, captain, mountain); ay (Sunday, Monday, Tuesday); e (evoke, pretty, heated, ticket, system, harmless, horses, extempore, apostrophe); ee (coffee); ei (foreign); ey (monkey, money, honey); i (it, hill, filth, lift); ia (carriage, marriage); ie (cities, dailies, ladies, lobbies); o (women); u (busy, minute (n.)); ui (build, guilt); y (rhythm, symbol, city, hilly, easy). It occurs initially, medially and finally and also occurs in accented and unaccented positions. /e/ In the production of vowel /e/, the front of the tongue is raised to a point about half-way between the halfopen and half-close positions; the lips are loosely spread and a little wider apart than for /ɪ/; the tongue is not as lax as for /ɪ/. This vowel can be described as a front un-rounded vowel between half-close and half-open. It is a short vowel. This vowel occurs for the spelling a (any, many, Thames, ate); ai (said, again); ay (says); e (end, send, let, get); ea (dead, spread, health, leant, jealous); ei (leisure, Leicester); eo (leopard, Leonard, Geoffrey); ie (friend); u (bury); ue (guess, guest). It occurs essentially in syllables carrying the primary accent and occurs initially and medially only. /æ/ In the production of this sound the front part of the tongue is raised to a little below the half open position. The lips are in the neutral position and the mouth is more open than for /e/. This vowel can be ISSN: 2250-138X Page 273 CONFLUENCE 26 February 2011 labeled as a front un-rounded vowel just below the half-open position. It is short vowel, but in front of voiced consonants it becomes as long as the ‘long’ vowels in the similar environments. For example in bat /bæt/ it is as much shorter than the /i:/ in beat /bi:t/ but in bad /bæd/ it is almost as long as the /i:/ in bead /bi:d/. This vowel occurs for the spelling a (ass, sat, hand, match); ai (plaid, plaid). It occurs only initially and medially. Back Vowels: /ɑ: / as in cart; /ɒ/ as in cot; /ɔ:/as in caught; /ʊ/as in full; /u:/ as in fool. /ɑ: / In the production of this vowel sound the jaws are considerably separated; the lips are neutrally open; and a part of the tongue between the center and the back is in the fully open position. It is long vowel and can be labeled as a back open un-rounded vowel. This vowel occurs for the spelling a (ask, dance, bath, after, mama); ah (ah); al (balm, calm, balm, psalm, half); ar (park, part, March, car); au (aunt, laugh); ear (heart, hearth); er (clerk, Derby, sergeant, Berkeley). It occurs mostly in accented syllables and initially, medially and finally. /ɒ/ In the production of this sound the back of the tongue raised slightly above the open position; the jaws are widely open and the lips are slightly rounded. It is a short vowel and can be called as a back rounded vowel just above the open position. This vowel occurs for the spelling a (after /w/) (was, what, want, watch, wash, quality /kwɒlItI); au (because, sausage, Austria, Australia, cauliflower); o (pot, dog, sorry, gone); ou (cough, trough, Gloucester); ow (knowledge). It occurs in accented syllables and in the initial and medial positions only. /ɔ: / In the articulation of this vowel sound the back of the tongue is raised between the half-open and halfclose positions; the lips are considerably more rounded than for/ɒ/. It is long vowel and can be described as a back rounded vowel between half-open and half-close. This vowel occurs for the spelling a (all, tall, wall, talk, chalk, salt, water); ar (warm, towards, quarter, war); au (cause, daughter, fault, slaughter, caught, caution); aw (awkward, law, raw, saw, straw, flaw, yawn lawn); oa (broad); oar (oar, board); oor (door, floor); or (or, nor, cord, sword, born, morning); ore (more, store, before); ou (ought, bought, fought, thought, nought); our (four, court, pour). This vowel occurs more often in accented than in accented positions and it occurs in all three positions – initial, medial and final. /ʊ/ This vowel is articulated by raising a part of the tongue nearer to center than to back just above the halfclose position; the lips are closely but loosely rounded. The tongue is lax. It is short vowel and can be described as a centralized back rounded vowel just above half-close. This vowel occurs for the spelling o (wolf, woman, bosom); oo (foot, good, book, look, wood, wool); ou (could, bull, would, courier); u (put, pull, sugar, push, butcher). A note should be taken here that it occurs in the word worsted (a kind of cloth) /wʊstId/. It occurs in both accented and unaccented syllables. In unaccented syllables its occurrence can be stressed in manhood, impudence, fulfill, concubine, bedroom. It occurs in the word medial position only (except in the case of the ‘weak forms’ of to and you where it can occur word-finally) and it does not occur before / ŋ /. ISSN: 2250-138X Page 274 CONFLUENCE 26 February 2011 /u:/ In the production of /u:/ the back of the tongue is raised to very near the close position. The lips are closely rounded and the tongue is tense. It is long vowel and can be described as a back close rounded vowel. It occurs in all three – initial, medial and final – positions but not before / ŋ /. It occurs in both accented and unaccented syllables. This vowel occurs for the spelling eau (beauty, beautiful) (pronounced /ju:/); eu (eulogy, eunuch, euphony) (pronounced /ju:/); ew (crew, blew, chew, grew); o (do, to (strong form), who, tomb, womb, prove); oe (shoe, canoe); oo (moon, room, food, soon, brood, route, you); u (flute, rude, June); ue (blue, true); ui (juice, fruit); wo (two). In words spelt with u, ue, ui, and ew, representing /u:/ the semivowel / j / is sometimes inserted before /u:/ as in unit, few. / j / is not inserted after / tʃ, dʒ, r, l /as in chew, June, rule, blue. / j / is regularly inserted after /p, b, t, d, k, g, m, n, f, v, h/ as in pure, beauty, tutor, duty, curious, argue, mute, few, view, hue. Usage varies after /s, z, θ/. Thus, suit, presume, enthuse are pronounced with / j / by some, and without / j / by others. Central Vowels: / ʌ / as in bus; / ɜ:ʳ/ as in learn; / ə / as in ago. /ʌ/ In the production of this vowel the centre of the tongue is raised to a point nearly half-way between open and half-open positions. In this position lips are neutrally open and there is considerable separation of the jaws. It is short vowel and can be described as a central un-rounded vowel between open and half-open. This vowel occurs for the spelling o (ton, son, one, monkey, colour, onion, oven, tongue, won, thorough); oe (does); oo (blood, flood); ou (trouble, double, southern, enough, young); u (sun, cut, shut, but). This vowel occurs essentially in accented syllabus. It occurs in initial and medial positions only and it does not occur before / ŋ /. / ɜ:ʳ/ In the production of this vowel the centre of the tongue is raised between half-close and half-open. The lips are in the neutral position. It is a long vowel and can be described as a central un-rounded vowel between half-close and half-open. This vowel occurs for the spelling ear (early, earth, learn, heard); er (serve, term, perfect, concern); err (err); ir (bird, firm, first, girl, shirt); or (when preceded by w) (word, world, work, worship); our (journey, adjourn); ur (burn, turn, hurt, murder, surface); urr (purr, currish); yr (myrtle). It occurs essentially in accented syllables. It occurs in all three positions – initial, medial and final but it does not occur before / ŋ /. /ə/ The vowel / ə / has two positions – the non-final and the final. The non-final / ə / is articulated the same way and at more or less the same place as the vowel / ɜ:ʳ/. In that position it differs from / ɜ:ʳ/ mainly in respect of length, / ə / being a short vowel. In the articulation of the final / ə / the centre of tongue is raised just below the half-open position. It is described as a central un-rounded short vowel. In the production of this sound lips are in the neutral position, in both the cases – non-final and final. It occurs in all the three positions – initial, medial and final, and in the unaccented syllables only. This vowel occurs for the spelling a (again, allow, woman, animal, drama, China); ar (particular, beggar, dollar); e (government, gentlemen, problem, reference); er (bothersome, otherwise, better, mother, singer); i (possible, terrible); ia (musician, magician, partial); o (consume, obtain, prolong); or (comfort, effort, actor, doctor, governor); ou (jealous, frivolous, famous); ough (thorough); our (labour, neighbour, colour); re (metre, ISSN: 2250-138X Page 275 CONFLUENCE 26 February 2011 centre); u (succeed, succumb, suspect (v)); ur (surprise, surmise (v), surpass ); ure (treasure, measure, feature). The teacher of English has to keep the three central vowels – / ʌ /, / ɜ:ʳ/, / ə / o – distinct. Diphthongs: Closing diphthongs gliding to [ɪ]: / eɪ, aɪ, ɔɪ / / eɪ / In the production of this diphthong the glide begins at a point just below the half-close front position and moves in the direction of / ɪ /. The movement of the tongue is accompanied by a slight closing movement of the lower jaw. The lips are spread. This vowel occurs for the spelling a (ace, race, take, bass (in music)); ai (aim, brain, slain, straight); ay (day, may, pray, say, stay); ea (break, great); ei (veil, eight, weigh, neighbour); ey (they, grey). This vowel occurs in all the three positions, initial, medial and final, and in both accented and unaccented syllables. / aɪ / In the articulation of the vowel / aɪ /, the glide starts from a point slightly behind the front open position and moves in the direction of / ɪ/. The movement of the tongue is accompanied by an appreciable closing movement of the lower jaw. The lips are neutral in the beginning but they change to a loosely spread position. It occurs initially, medially and finally, and in the accented and unaccented syllables. This vowel occurs for the spelling ai (aisle); ei (either, Einstein); eye (eye); i (die, lie, cried, tried); uy (buy, guy); y (try, my, shy, fry, type); ye (bye, dye). /ɔɪ/ This vowel begins at a point between half-open and open positions and moves in the direction of /ɪ/. The jaw movement is not as considerable as for the diphthong / aɪ /. At the beginning the lips are open rounded and they change to neutral towards the end. It occurs in all the three positions – initial, medial and final. It generally occurs in accented syllables and in very few unaccented syllables: exploit (n) and employee. This vowel occurs for the spelling oi (oil, boil, toil, voice, noise, join); oy (toy, boy, annoy, employ). It should be noted /ɔɪ/ in buoy and is pronounced like boy /ɔɪ/. Closing diphthongs gliding to [ʊ]:/ aʊ, əʊ/ /aʊ/ This vowel begins at a point between back and front open positions and moves towards / ʊ /. The starting point may be almost half-way between the back and the front, often nearer the back than the front. The lips are neutral at the beginning of the glide but become rounded towards the end. The jaw movement is as extensive as for the diphthong / aɪ /. This vowel has a symmetrical relationship with / aɪ /. It occurs initially, medially and finally and only in accented syllables. It’s occurrence in unaccented syllables is confined to compounds formed by the affixation out- and –how. This vowel occurs for the spelling ou (out, round, doubt, sound, mouth); ow (how, cow, town, allow, now). /əʊ/ ISSN: 2250-138X Page 276 CONFLUENCE 26 February 2011 The glide for the vowel / əʊ / begins at a central position almost midway between half-close and half-open and moves in the direction of /ʊ/. The jaw movement is very slight. The lips are neutral at the beginning and become rounded towards the end. It occurs initially, medially and finally and in both accented and unaccented syllables. This vowel occurs for the spelling o (old, open, bold, home, go, no, don’t, won’t); oa (oak, oaf, boat, road, goal, boast); oe (tow, doe, foe, hoe); ou (though, mould, soul, smoulder); ow (own, bowl, blow, slow). Centring diphthongs gliding to [ə]: / ɪəʳ, eəʳ, ʊəʳ/ /ɪəʳ/ The glide for the vowel sound / ɪəʳ/ begins at approximately the half-close centralized front vowel / ɪ/ and moves in the direction of the opener variety / ə /, when / ɪəʳ/ is final in the word (as in fear, clear), and towards the less open variety of / ə /, when it is nit final in the word (as in feared, clears). The lips remain neutral throughout the process. This vowel occurs for the spelling e (zero, serious, period); ea (idea, theatre, real); ear (dear, clear, fear); eer (deer, cheer, beer, sheer); eir (weird); ere (here, mere, severe); eo (theory, theorem, theological); eu (museum); ia (Ian, India); ier (fierce, bier, tastier); io (period); iou (serious, impious). Although it its occurrence in the initial position is highly restricted, it occurs initially, medially and finally. It occurs in both accented and unaccented syllables. In the vowel / ɪəʳ/, the first element / ɪ / is more prominent than the second element / ɪəʳ/ when the vowel occurs in an accented syllable as in theory / θɪərɪ / and idea /aɪdɪə /. In such cases the diphthong is called a falling diphthong. When the diphthong occurs in an unaccented syllable, the second element / ə / is more prominent than the first element / ɪəʳ/ as in idiom / ɪdɪəm / and theoretical / θɪəretɪkl /. In such cases the diphthong is called a rising diphthong. / eəʳ/ The glide for the vowel / eəʳ/ begins in the front, above the half-open position, and moves in the direction of / ə /. The glide is in the direction of the opener variety of / ə / if it occurs word-finally (care, stare) and in the direction of the less open variety of / ə / if it occurs non-finally in a word (airy, compared). The lips remain neutrally open throughout the process. It occurs in both accented and unaccented syllables with a strong tendency to occur in accented syllables and it occurs initially, medially and finally. This vowel occurs for the spelling a (various, hilarious, aquarium, Mary); air (air, chair, fair, despair); ar (scare); are (care, share, stare, beware); ear (bear, pear, wear, tear); eir (their, heir); ere (there, where, ere, compere). /ʊəʳ/ /ʊəʳ/ begins its glide from the tongue position for / ʊ/ and moves in the direction of / ə /. Its glide is towards the opener variety / ə / if the diphthong occurs word-finally (poor, sure) and it is towards the less open variety of / ə / (dual, steward). The lips are loosely rounded at the beginning of the glide and neutral at the end. It is falling diphthong when it occurs in an accented syllable (fluency and injurious). Here the first element is more prominent than the second. When it occurs in an unaccented syllable (influence and individual) is rising diphthong and it can often be replaced by [wə]. It occurs in both accented and unaccented syllables and in the medial and final positions only. This vowel occurs for the spelling oor (poor, moor); our (tour, gourd, gourmet); u (jury, rural, mural, luxurius); ua (manual, truant, casual); ue (fluent, influence, fuel); uou (torturous); ure (sure, pure, cure). ISSN: 2250-138X Page 277 CONFLUENCE 26 February 2011 To conclude all the twenty vowels of RP are oral, each representing in the writing system by different letters and their combinations. Twelve are monophthongs or pure vowels and eight are diphthongs or impure vowels. All the diphthongs are ‘long’. The five pure vowels /i:, ɑ:, ɔ:, u:, ɜ:, / are ‘long’. Monophthongs are divided into front, central and back. Of the five back vowels only four / ɒ, ɔ:, ʊ, u:/ are rounded vowels and all other are un-rounded. The lip-rounding increases as the height of the tongue increases when it is the matter of the rounded vowels. /ʊ/ occurs only medially; / e, æ, ɒ, ʌ / initially and medially; and remaining seven occur in all the three positions. The diphthongs are grouped into two categories: closing and centring diphthongs. Of the eight diphthongs, three glide towards [ɪ]; two towards [ʊ] and the remaining three towards [ə]. It is the vowel sounds that trouble to the second language learners form India and other places. The enough oral practice has to be given to the learners and it becomes the responsibility of the English teacher as there is no other way to train the learners in the practice of second language acquisition. But in the Indian school curriculum the ‘ear training’ is lacking. ISSN: 2250-138X Page 278 CONFLUENCE 26 February 2011 Appendix: The following chart shows the IPA (International Phonetic Alphabets) for Vowel and Consonant sounds in English (www.antimoon.com/how/pronunc-soundsipa.htm): Vowel Sounds IPA examples Consonant Sounds IPA examples ʌ cup, luck b bad, lab ɑ: arm, father d did, lady æ cat, black f find, if e met, bed g give, flag ə away, cinema h how, hello ɜ:ʳ turn, learn j yes, yellow ɪ hit, sitting k cat, back l leg, little i: see, heat ɒ m man, lemon hot, rock n no, ten ɔ: call, four ŋ sing, finger p pet, map r red, try s sun, miss ʃ she, crash t tea, getting ʊ put, could u: blue, food aɪ five, eye aʊ now, out eɪ say, eight əʊ go, home tʃ check, church ɔɪ boy, join θ think, both eəʳ where, air ð this, mother ɪəʳ near, here v voice, five w wet, window ʊəʳ pure, tourist ISSN: 2250-138X Page 279 CONFLUENCE 26 February 2011 z zoo, lazy ʒ pleasure, vision dʒ just, large Works Cited: ISSN: 2250-138X Page 280 CONFLUENCE 26 February 2011 1. Balsubramanian, T. A Textbook of English Phonetics for Indian Students. Delhi: Macmillan, 2001, Reprint 2. Chin, Ng Bee & Gillian Wigglesworth. Bilingualism. London & New York: Routledge, 2007 3. Gleason, H. A., Jr. An Introduction to Descriptive Linguistics. New Delhi, Bombay, Calcutta: Oxford & IBH, 1968, Revised Edition 4. Harrison, Brian (ed.). Culture and the Language Classroom. Hong Kong: Modern English Publications, 1990 5. Jones, Daniel. English Pronouncing Dictionary. New Delhi: Universal Book Stall, 1993, 14th Edition 6. Jones, Daniel. An Outline English Phonetics. Ludhiana, New Delhi: Kalyani Publishers, 1990, 9th Edition 7. Lado, Robert. Language Teaching: A Scientific Approach. Bombay, New Delhi: Tata McGraw Hill, 1986, Seventh Edition 8. Littlewood, William. Teaching Oral Communication. Oxford UK and Cambridge USA: Blackwell, 1992 9. Sethi, J. & P. V. Dhamija. A Course in Phonetics and Spoken English. New Delhi: Prentice Hall, 2000, Second Edition 10. Varshney, Dr. Radhey L. An Introductory Textbook of Linguistics & Phonetics. Bareilly: Student Store, 2007-08, Sixteenth Reprint 11. www.antimoon.com/how/pronunc-soundsipa.htm 12. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Vowel ISSN: 2250-138X Page 281