Africa in Transition Presentation - Darryl de Ruiter

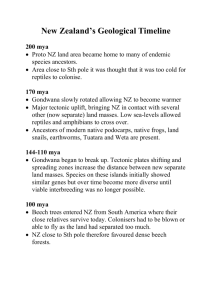

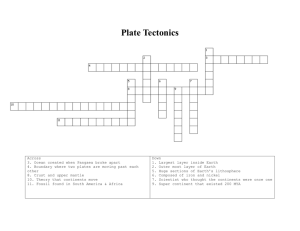

advertisement

Africa in Transition: Politics, Culture, Agriculture, Anthropology, Education The pre-history of Africa: searching for the origins of modern humans in South Africa Darryl de Ruiter, Department of Anthropology Evolution and Natural Selection Darwin’s genius was not recognizing that evolution occurred, as the concept of evolutionary change was widely held in the 1800s. Instead, Darwin was the first to describe the mechanism by which evolution operated, which he termed “natural selection”. • • • • • Species produce more offspring than can survive (there is a struggle for life) There is biological variation within all species (all animals differ in small ways) Individuals possessing favorable traits are more likely to survive and produce offspring (which traits are favorable depends on the environment in which an animal lives) Inherited traits are passed on to the next generation (genetic transmission) Variations accumulate over long periods of time (over thousands or millions of years, new species will arise) As has been pointed out recently, evolution is just a theory. However, it is important to note that in science, a theory is an explanation that has undergone rigorous testing, in an attempt to falsify the idea. After an idea has been tested over and over, and has survived multiple attempts to prove it wrong, it can be considered a theory. So, far from being a weak word in science (just a theory), the theory of evolution is an indication of how powerful the notion actually is (a strongly supported theory). By way of example, other ideas that can be labeled as “just a theory” include Einstein’s theory of relativity, biological cell theory and the theory of plate tectonics. Few people would argue that gaps in our knowledge of these theories must prove them to be categorically wrong. Plate tectonics This theory suggests that the earth’s crust is divided into several plates that move atop a mantle of magma. In places where plates collide, they drive up mountain ranges and cause volcanic activity. In places where plates are being torn apart, volcanic activity also occurs, in particular in the South Pacific ocean. Milankovitch Cycles These are fluctuations in the earth’s orbit around the sun. They include such changes as differences in the tilt of the earth’s rotational axis, changes in the orbit from circular to more elliptical, and alterations in the relative positions of the continents at various distances from the sun. Dating Fossils Carbon 14 is a dating technique that measures the amount of radioactive carbon (14C) compared to non-radioactive carbon (12C) to determine how much time has passed since an organism died. Potassium-Argon (K-Ar) dating measures the amount of argon gas that builds up in volcanic crystals relative to the amount of radioactive potassium present since a volcanic eruption. Biostratigraphy is used when there are no radioactive materials in a fossil deposit, and relies on comparing the types of animals found in a nonradioactive site to those that are known from a better dated radioactive site. Taphonomy Taphonomy is the study of everything that happens to an animal’s bones from the time it dies, through fossilization, and ultimately to the excavation of the bones by archaeologists and paleontologists. Early paleoanthropologists assumed that australopithecines were the dominant hunters on the planet, though later research showed that they were, in fact, the victims of larger predators. The Fossil Hominins Earliest potential hominins (7.0 – 5.0 Million years ago (Mya)) There is a great deal of debate over whether these groups qualify as hominins. We must keep in mind that this debate does not weaken the case for human evolution, but rather, demonstrates the volume of fossil evidence that is already available. Sahelanthropus tchadensis 7.0 – 6.0 Mya, Sahel Desert, Chad pronounced supra-orbital torus (a ridge of bone above the eyes) weak facial prognathism (prognathism = protruding jaws, like an ape) reduced canine dentition intermediate enamel thickness (humans have very think tooth enamel) nuchal area (where neck muscles attach) suggests bipedalism Orrorin tugenensis 6.0 Mya, Tugen Hills, Kenya small teeth with thick enamel femora indicate bipedalism large body size Ardipithecus ramidus 5.8 – 4.4 Mya, Middle Awash River, Ethiopia forward positioned foramen magnum (hole for spinal cord at base of skull) large post-canine teeth with thin enamel large, non-projecting canines probably bipedal, but not certain; knuckle-walking can be ruled out Ardipithecus ramidus known from a woodland rather than savanna setting although thin-enameled teeth, a trend toward powerful chewing had already begun Later definite hominins (5.0 – 1.0 Mya) All of these fossil groups are considered to be in the human family tree, though there is debate over which particular group lead directly to humans. Again, this debate demonstrates the strength of the fossil evidence, not an absence of evidence. We have so much fossil material, it is hard to pick which is our ancestor, and which is a close relative that was not directly ancestral to us. This debate is fueled in large part by the virtual explosion of tremendous new fossil discoveries in the last 5-10 years. Australopithecus anamensis 4.2 – 3.9 Mya, Lake Turkana, Kenya male body size larger than A. afarensis, females about the same size as A. afarensis large post-canine dentition, with moderately thick enamel reduced size of canines parallel tooth rows similar to apes includes human looking tibia found nearby lived in open woodland with nearby river Australopithecus afarensis 4.0 – 2.9 Mya, Ethiopia, Kenya, Tanzania mosaic of human-like and ape-like features in the skull and skeleton enlarged molars with thickened enamel fully bipedal in most aspects of the post-cranial skeleton still capable of movement in the trees closed woodland/forest near a permanent water source with edaphic grasslands the species exhibits morphological stasis for more than 1.0 My “Kenyanthropus platyops” 3.5 Mya, Lake Turkana, Kenya broad, flat face minimal prognathism size and positioning of teeth claimed to differ from Australopithecus lived in woodland with edaphic grasslands and shallow wetlands/swamps Australopithecus garhi 2.5 Mya, Middle Awash River, Ethiopia enlarged molar dentition, along with enlarged anterior dentition more thickened molar enamel cranial features can be aligned with either Australopithecus or early Homo associated with stone tools and cut-marked bone the discoverers considered that this species may be derived from A. africanus, and ancestral to Homo Australopithecus bahrelghazali 3.5 Mya, Koro Toro, Chad vertical mandibular symphysis (chin region) premolar with 3 roots controversial species however, its geographical location 2500km west of the Rift Valley may be of particular relevance Australopithecus africanus 2.5 – 2.0 Mya, South Africa dolichocephalic (long and narrow) skull – unlike chimps no supra-orbital tori, slight prognathism; forward positioned foramen magnum humanlike dentition open woodland with nearby river and edaphic grasslands possesses long arms and short legs, more similar to chimps than to humans nonetheless, this is a bipedal animal Paranthropus aethiopicus 2.7 – 2.3 Mya, Kenya and Ethiopia extreme development of cranial cresting flat, flaring face roots indicate very large teeth woodland with riverine forest and edaphic grasslands possibly forms an intermediate between earlier A. afarensis and later P. robustus and P. boisei Paranthropus boisei 2.3 – 1.5 Mya, Tanzania, Kenya, Malawi robust cranial cresting patterns hyper-robust dentition broad, flat face scrub woodland with nearby edaphic grasslands very well represented taxon throughout East Africa first australopithecine to be dated by K-Ar Paranthropus robustus 2.0 – 1.0 Mya, South Africa broad, flat face (dished face) large molar teeth, reduced anterior teeth well developed cranial crests, but not as powerful as other Paranthropus often referred to as an open, arid grassland specialist however, they appear to prefer more closed portions of a mosaic habitat they display tremendous dietary diversity Homo habilis 2.4 – 1.6 Mya, Tanzania, South Africa, Malawi, Ethiopia, Kenya cranial trends: increased brain size and complexity (650cc) reduction in facial size reduced reliance on chewing larger brains produce rounder skulls forehead begins to appear incisors large, other teeth reduced in size (similar to modern humans) first human ancestor to leave traces of stone tools Homo erectus 1.9 – 0.4 Mya, Ethiopia, Kenya, Tanzania, South Africa, also Asia and Europe long, low cranium flat frontal bone with pronounced supra-orbital torus significant post-orbital constriction (narrowing behind orbits) midline thickening of frontal bone – frontal keel extremely thick cranial vault bones cranial capacity ranging from 700 – 1300 cc, averages about 900 cc large robust mandibles lacking mental eminence (chin) molar teeth have large pulp cavities (taurodont) and upper central incisors are shovel-shaped left stone tools (hand axes) scattered throughout Africa; tools appear unchanged for more than one million years Homo floresiensis 18000 years ago; Flores Island, Indonesia very diminutive hominids associated with pygmy elephants 18 000 years old!!! Controversial!!! The body proportions are not like a human shrunk down, but rather like Homo erectus shrunk down Controversial!! Middle Pleistocene Homo 1.0 – 0.2 Mya major morphological changes relative to Homo erectus: increase in brain size a shift from the widest part of the brain case from the cranial base to the parietal regions more vertical nose reduction in muscular robusticity many scientists argue over whether this represents an actual species, or a loose collection of human-like ancestors; however, no one doubts that these are in some way ancestral to modern humans Modern Humans 0.2 Mya – present There are three main theories regarding the origin of modern humans. Multiregional Continuity – regional populations of middle Pleistocene Homo gradually evolved into modern human populations that occupy those regions today Out of Africa: modern humans evolved in Africa and spread outwards, replacing all other archaic populations worldwide Partial Replacement: modern humans evolved in Africa and spread outwards, but interbred with local populations, eventually genetically swamping them