THESIS - eCommons@Cornell

advertisement

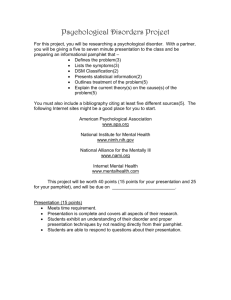

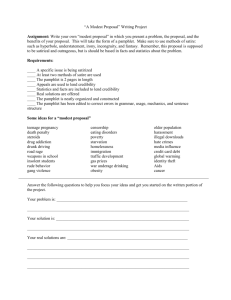

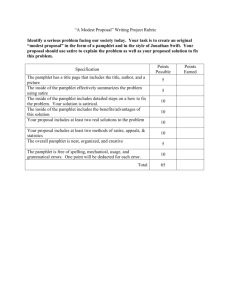

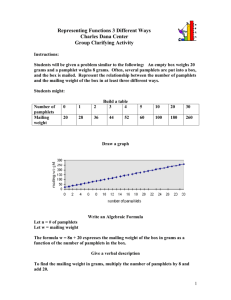

Getting the Message Across Running head: OLDER ADULTS AND HEALTHCARE DECISION-MAKING Getting the Message Across: Examining Information Presentation and Healthcare Decision Making Among Older Adults Andrea Shamaskin Cornell University 1 Getting the Message Across 2 Abstract Previous research has demonstrated that the valence of healthcare messages influences attitudes, and that the processing of valenced information changes with age (Carstensen & Mikels, 2005; Levin, Schneider, & Gaeth, 1998). Study 1 examined differences in health opinions and memory by presenting twenty-five older adults (M = 74.5 years) and twenty-four younger adults (M = 20.3 years) positively and negatively framed messages in healthcare pamphlets. Older adults rated positive pamphlets more informative than negative pamphlets and remembered positive versus negative messages better than younger adults. There were no age differences in health attitudes between positive and negative pamphlets. Study 2 replicated Study 1 using physician vignettes rather than pamphlets, yielding results trending in the predicted direction with positive physicians rated more informed than negative physicians. These findings demonstrate a positive bias in older adult memory, as well an influence of valence on their perceptions of informative value. Getting the Message Across 3 Getting the message across: Examining information presentation and healthcare decision making among older adults People are bombarded with messages about their health; television commercials, radio advertisements, and even billboards contain information persuading people to buy a certain product or talk to their doctor about an issue. Considering the vast amounts of money and time spent creating these messages, one wonders about the actual impact of this information. The purpose of the present study was to explore whether message effectiveness and memory for messages varies across different populations, in particular between older and younger adults. A secondary goal of this study was to explore message effectiveness in a social context, using physicians as an information source. Older adults, generally considered those aged 60 or older, are more likely than younger age groups to face medical issues and, as such, make decisions about their healthcare more frequently. Several decades ago, healthcare decision making among older adults focused on managing illness and “damage-control,” but considering increasing life expectancies, healthcare messages today have the opportunity to influence older adults’ preventative behaviors for certain illnesses as well. In order to persuade people to perform risk-reducing and health-promoting behaviors, it is crucial to understand how to present information to older adults in the most effective way. Methods of Information Presentation There are several common varieties of healthcare advertisements, including before-andafter photographs, statistics of treatment outcomes, or statements addressing healthcare behaviors. One way to change how this information is presented is through message framing. Framing effects demonstrate that people’s preferences for a particular choice can be shifted Getting the Message Across 4 depending on how the information is presented, even if the options are objectively identical (Tversky & Kahneman, 1981). For example, risky-choice framing influences people’s risk preferences, as people tend to choose a sure outcome when information is framed positively, whereas negatively framed information influences people to choose a more risky option. Tversky and Kahneman’s (1981) “Asian disease problem” is the classic example of risky-choice framing. In this paradigm, the researchers found that the majority of subjects chose the certain outcome when the situation was presented in positive terms (a guarantee of saving of one-third lives), however they chose the risky option when the situation was presented in negative terms (a one-third chance of losing no lives and a two-thirds chance of losing all the lives). From this noteworthy study, researchers have pursued how framing a problem can influence decision making through a variety of contexts and differing types of frames (for a review see Levin, Schneider, & Gaeth, 1998). Many health-related messages use a particular type of framing, known as goal framing, to focus on people’s health related behaviors. Goal framing emphasizes performing a particular behavior to either receive a benefit or avoid a negative consequence. For example, a positive frame might read, “You can gain several potential health benefits by talking to your doctor about high cholesterol. Take advantage of this opportunity.” Conversely, the negative frame would read, “You can lose several potential health benefits by failing to talk to your doctor about high cholesterol. Don’t fail to take advantage of this opportunity.” Both of these statements target the same behavior (i.e. talking to a doctor about high cholesterol), however they have clearly opposite emotional tones. This type of frame is unique because both the positive and negative frames are aimed at encouraging the same end result—the difference between frames is whether Getting the Message Across 5 it emphasizes receiving a health benefit of a behavior or avoiding a loss by performing the same behavior. Meyerowitz and Chaiken (1987) demonstrated the effect of goal framing in a study that examined framing influences on women’s likelihood to engage in breast self-examinations (BSE). They found that the women were more motivated to perform BSE through a negative goal frame than they were to do BSE through a positive goal frame. They explained these findings in that negative information has a more powerful effect on judgment and behavior than positive information (i.e., a negativity bias). Other research on goal framing has shown that when health information is processed deeply, negatively framed messages have a stronger impact on behavior than positively framed messages (Block & Keller, 1995). Levin, Schneider, and Gaeth (1998) argued for the same conclusion in their review of numerous goal-framing studies. Some studies, however, have suggested differing results based on participant level of involvement and perception of the addressed behavior as risky or not (Maheswaran & MeyersLevy, 1990; Rothman, Salovey, Antone, Keough, & Martin,1993). While these reevaluations of goal framing studies focus on nuances such as preventative or detection based behaviors and participant self-involvement in the targeted behavior, most of the research has not used agespecific participant populations to investigate age-differences in goal framing. Nonetheless, there has been some research examining general framing effects between younger and older adults. Kim, Goldstein, Hasher, and Zacks (2005) found that older adults show increased framing effects as compared to younger adults for two risky-choice problems. On the other hand, another study discovered limited differences in framing between older and younger adults, again presenting participants with several risky-choice scenarios (Mayhorn, Fisk, & Whittle, 2002). Lastly, recent research found that the influence of frame does change with Getting the Message Across 6 age, as older adults were less risk-seeking (or less biased) in the loss frame than younger adults (Mikels & Reed, in press). While these studies present somewhat conflicting results, a crucial point and common thread between all three is that the studies focus only on framing with risky decision-making. Within risky-choice framing, the positive frame describes options in terms of gains. The negative frame instead focuses on an option in terms of loss. In a sense, this type of frame asks people to make an objective decision and choose between two options, with these options being essentially equal in value but presented in a positive or negative way. Goalframing influences people’s choices and decisions in an inherently different way than riskychoice framing. With goal-framing, both the positive and negative frames target the same behavior, and the difference between frames refers to individual consequences from performing or not performing the behavior (Levin, Schneider, & Gaeth, 1998). There is good reason to believe that goal-framing might function differently between older and younger adults. In the context of goal-framed healthcare information, participants are assessing a message that relates to their own health and informs them of the consequences or benefits for their bodies. These goals are very emotionally salient, and one could expect that these frames would prompt an emotional response in older adults, more so than with risky-choice framing. This idea is also supported by socioemotional selectivity theory (Carstensen, Isaacowitz, & Charles, 1999), which proposes that as people age they are more motivated to pursue emotionally meaningful goals. Based on this theory, a frame that evokes a more emotional response or processing would presumably function differently between older and younger adults because of these variations in motivational goals and emotion. Age Differences Regarding Positive and Negative Information Getting the Message Across 7 In contrast to the existing literature on goal-framing effects (Block & Keller, 1995; Levin, Schneider, & Gaeth, 1998), an emerging body of research suggests that the relative influences of positive and negative information shifts as people age, with older adults showing a preference for positive versus negative information (Carstensen & Mikels, 2005). The positivity effect is a developmental trend that demonstrates a shift in preferences, with younger adults favoring negative information followed by a shift in adulthood in which older adults prefer positive information. The positivity effect shows that older adults attend to emotionally positive information, are able to keep it in mind, and remember it better than negative and neutral information. There has been a variety of research examining the positivity effect in regard to older adults’ memory for positive and negative information. Charles, Mather, and Carstensen (2003) found that while there was an overall decrease in image recall with age, the ratio of positive to negative images recalled increased with age, the highest ratio being with older adults. Mikels, Larkin, Reuter-Lorenz, and Cartensen (2005) discovered this bias with working memory, demonstrating that older adults remembered positively valenced emotional information better than negative emotional information. Other research found this effect even in older adults’ construction of the past, as older adults remembered the past more positively than they originally reported several years earlier (Kennedy, Mather, & Carstensen, 2004). Lastly, recent research has supported this suggestion through findings that older adults recalled more false positive than false negative memories in three different recall tasks (Fernandes, Ross, Wiegand & Schryer, 2008). These authors note that false-memory data in older adults reflects strongly on the positivity effect, in that older adults recreate the past to emphasize the positive. Overall, these findings suggest a potential bias or even systematic distortion in the type of information that Getting the Message Across 8 older adults remember. Considering these intriguing results, one might expect that when older adults are drawing upon their cognitive resources to make a decision, positive information would be more readily recalled or have a stronger influence than negative information. This shift in preference for positive information as people age is based on the concept that people’s emotional experiences and goals change as they age. Carstensen, Isaacowitz, and Charles (1999) proposed that people’s goals and motivations are based in a temporal context, with younger adults usually having a more open time perspective and older adults having a limited time perspective. People with an open-ended time perspective are motivated to seek out information and create novel relationships, in preparation for future life experiences where this knowledge would be important. Those with a limited time perspective, as the theory posits, are more focused on achieving emotionally meaningful goals and investing in emotional aspects of their lives. They have a sense of the boundaries on their time, and as such, strive to fulfill emotionally meaningful relationships and feel connected with others. Since the foundation for this theory is in motivation towards emotion regulation, goal-framing is certainly appropriate because it manipulates the consequence or goal of a certain personal behavior and influences people at an emotional level to consider their own outcome. Purpose of Study The purpose of the current study was to examine how framing health information in emotionally positive ways or emotionally negative ways may lead to different attitude and memory outcomes between older and younger adults. Essentially, this is an investigation of the interaction between the positivity effect and framing effects, particularly the emotionally salient goal-framing. By implementing the positivity effect through the context of goal-framing, we can better understand the strength of its influence in the health domain, as well as the factors that Getting the Message Across 9 might weaken the effect. This experiment followed Meyerowitz and Chaiken’s (1987) model of goal-framing, in which they presented information in pamphlet form in distinct positive and negative frames. After developing our own pamphlets, we gathered information about attitudes, intent to perform certain health behaviors, and informative value of the pamphlets. These postexperimental questions were adapted from measures used in three different studies that examined goal-framing with health information (Block & Keller, 1995; Meyerowitz & Chaiken, 1987; Rothman et al., 1993). Finally, participants completed a surprise statement recognition task regarding the information presented. This final memory task was intended to assess if there was an age-related difference in delayed memory of the framed messages. In real-world situations, people are often provided information about a healthcare issue but then must rely on their memory as they make a decision days, weeks, or months later. This last portion of the experiment investigated whether positive or negative information was remembered differently after a delayed period of time. Although the current study used a statement recognition task rather than a memory recall task, it forced participants to rely on their memory regarding information they read in the pamphlets. As the memory feature of the experiment was completed several minutes after reading the pamphlets, we expected this task to be moderately difficult. This delayed memory task presumably caused participants to choose based on what they believe they remembered, thus creating an opportunity to observe older adults’ preferences in information valence. Based on the previous literature on goal framing and the positivity bias seen in older adults, there were two major hypotheses for this portion of the experiment. First, it was expected that older adults would be more influenced in their overall attitudes and intentions to perform prevention/detection behaviors regarding health issues from a positive frame than a negative Getting the Message Across 10 frame. Second, it was predicted that older adults would better remember positively framed messages from the information pamphlets than negative messages. We expected that this effect to manifest itself in that older adults’ proportion of positive to negative statements remembered would be higher than the relative proportion for younger adults. The goal of this investigation was to contribute new research examining lifespan differences in framing effects, as evaluated through the lens of the positivity effect. Additionally, we hoped to support the current research on emotion and memory across the lifespan by demonstrating that older adults’ memory for positive information is better than negative information. In another direction, if objectively negative information is systematically remembered as positive, this pattern of results could demonstrate a memory distortion. These findings would have implications for developing strategies of information presentation with older adults. A piece of information may vary in its degree of influence depending on whether decisions are made immediately after the information is presented or after a delayed period of time. Method Participants Twenty-five older adults ranging from 64 to 86 years of age (M = 74.52 years, SD = 6.01 years; 16 females & 9 males) and twenty-four Cornell University undergraduates ranging from 18 to 23 years of age (M = 20.27 years, SD = 1.24 years; 13 females & 11 males) participated in this experiment. Older adults were recruited from the Ithaca, NY community and were compensated $30 for their participation. Younger adults received course credit for their participation. Materials Getting the Message Across 11 Pamphlet. Participants read four pamphlets that provided information about different healthcare issues. Although realistically most health issues are more significant for older adults, we chose particular health issues that would be matched on salience between older and younger adults. The four health domains selected were influenza, cholesterol, skin cancer and sexually transmitted diseases. These domains were also chosen in an effort to balance the saliency of the health issue, with influenza and sexually transmitted diseases presumed to be more relevant to younger adults and cholesterol and skin cancer more significant for older adults. Each pamphlet focused on one of these health domains, and they were designed to look very similar to a pamphlet or brochure that might be found in a physician’s office (See Figures 1 and 2 for examples of pamphlet designs). They included general information about a particular health domain, which was gathered from a reputable online health database (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; “Cholesterol”, 2007; “Key Facts About Seasonal Influenza (Flu)”, 2008; “Basic Information About Skin Cancer”, 2008; “STD-Health Communication-Fact Sheets”, 2008). Each pamphlet contained four statements that referred to actions or behaviors a person could perform regarding their personal health with the disease or illness described. These statements were modeled after Meyerowitz and Chaiken’s (1987) BSE study. As in their experiment, statements were manipulated through the context of goal-framing to create two pamphlets for each health domain, one including four positively framed statements and one with four negatively framed statements. Pamphlets within each domain were identical except for these four statements. For example, participants viewing the positive skin cancer pamphlet read: “People who routinely check their own skin for changes or new growths are more likely to notice potential signs of skin cancer”. Another participant viewing the negative skin cancer pamphlet Getting the Message Across 12 read: “People who fail to routinely check their own skin for changes or new growths are less likely to notice potential signs of skin cancer”. Procedure The design of this experiment used E-Prime experimental software which assigned each participant to read four pamphlets, with a counter-balanced assignment for two pamphlets to include negative framing and two to include positive framing. The program also controlled for order effects between participants, with the four pamphlets read in a randomized order. Instructions for the experiment were presented on a desktop computer screen, however a researcher was in the room throughout the experiment to answer any questions. Before reading the pamphlets, participants were asked if they had a history of any of the four health domains that would be used in the study. Participants then read one pamphlet at a time, and were given an unlimited amount of time to read each pamphlet. When participants finished reading one pamphlet, they returned the pamphlet to the researcher conducting the experiment. Participants were instructed that they would answer several questions on the computer about the pamphlet they had previously read. They responded to five questions that asked about their attitudes, perceived vulnerabilities and intended health behaviors regarding the health issue, as well as the informative value of the pamphlet they just read. These questions were modeled from the postexperimental questions used in three goal-framing healthcare studies (Block & Keller, 1995; Meyerowitz & Chaiken, 1987; Rothman et al., 1993) (See Appendix A). All questions asked participants to respond on a 7-point Likert-type scale. This process was repeated for all four pamphlets. After reading and rating the pamphlets, participants completed a surprise statement recognition task, intended to evaluate their memory of the information provided in the pamphlets. In total up to this point, each participant had viewed 16 Getting the Message Across 13 framed statements (4 statements in each pamphlet X 4 domain-specific pamphlets). In this final portion of the experiment, participants viewed a pair of statements, containing one statement that they saw in one of the pamphlets they read, while the other statement was informationally equivalent but oppositely-valenced. For example, in one of the 16 recognition trials, a participant were presented two statements on the computer screen: “Research shows that people who regularly check their cholesterol levels have an increased chance of recognizing their risks for other related health issues.” [positive frame] “Research shows that people who do not regularly check their cholesterol levels have a decreased chance of recognizing their risks for other related health issues.” [negative frame] Participants were asked to identify which statement they remembered reading in the pamphlet. This process continued for the 16 pairs of statements. The order that the statements were presented was counter-balanced by statement valence. The positive statement appeared first for half of the pairs and the negative statement first for the other half in order to avoid any response biases in consistently choosing the first statement. Additionally, the order of the statement pairs regarding domain was randomized in an attempt to control for primacy or recency effects. Finally, participants were debriefed on the experiment and thanked for their participation. The approximate time of the experiment was 25-30 minutes. Results Post-pamphlet questions 1 through 5 conceptually measured different constructs regarding attitudes toward the health issue, intended behaviors, and the informative value of each pamphlet. Predictably, the reliability between these outcome scores was moderately low (Chronbach’s alpha = 0.61). Therefore, we conducted our analyzes on each individual question. There was a significant effect of gender for Question 5, with females reporting across domains Getting the Message Across 14 that the pamphlets were more informative (M = 5.39, SD = 0.27) than males (M = 4.38, SD = 0.33), F (1, 47) = 5.51, p < .05. The scope of this study, however, does not address gender differences, and this result will not be discussed further. It also is worth noting that the gender effect could be attributable to having nearly twice as many female as male participants. Preliminary analyses revealed no effects for pamphlet order. Thus in the following analyses, we assume no order-effects or effects from participant fatigue. The data were analyzed in a mixed-model Analysis of Variance (ANOVA), with age, valence, domain, and personal history as fixed factors and subject as a random factor. Pamphlet Ratings There was a main effect of age for three of the five post-pamphlet questions. Older adults had higher ratings than younger adults for Question 1, Question 3, and Question 5 (See Table 1). There was an effect of pamphlet valence for Question 5, in which the positive pamphlets were rated more informative (M = 5.18, SD = 0.21) than the negative pamphlets (M = 4.80, SD = 0.21, F (1, 135) = 8.60, p < .05. There were no effects of pamphlet valence on any of the other post-pamphlet questions. Interaction Effects There were no significant interactions between age and valence, F (1, 135) = .01, ns, for four of the five post-pamphlet questions. There was an interesting interaction between age and valence for Question 5, which asked participants how informative they believed the pamphlet was, F (1, 135) = 7.83, p < .05 (See Figure 3). Older adults reported that positive pamphlets were more informative (M = 6.01, SD = 0.29) than the negative pamphlets (M = 5.34, SD = 0.29), while younger adults did not differ in this rating (M = 4.28, SD = 0.29 for positive pamphlets, M = 4.27, SD = 0.29 for negative pamphlets). There was also a three-way interaction Getting the Message Across 15 between age, valence, and domain for Question 5 (F (1, 86.92) = 2.98, p < .05), in which across all four health domains, older adults rated the positive health pamphlets as more informative than the negative health pamphlets. This difference, however, did vary somewhat between health domains, with larger differences between the positive and negative cholesterol and skin cancer pamphlets than between the influenza and sexually transmitted diseases pamphlets. Pamphlet Domain and Participant History There was a main effect of pamphlet domain across all five post-pamphlet questions (See Table 2). However, since there were no predictions regarding differences in pamphlet domain, this result will not be discussed further. There was a cross-over interaction between the participant age and personal history for three of the five post-pamphlet questions (See Table 3). Across all domains, older adults who confirmed they had a history of the health issue responded higher on scales measuring intentions to perform health behaviors and the informative value of the pamphlet than those who reported no history. Younger adults, on the other hand, showed an opposite effect. Those who confirmed that they had a history of the health issue responded lower on these scales than those who had no history of the issue. We also note that there was an interaction between age and personal history for Question 1, however this was not in the predicted direction. Recognition Performance For the statement recognition task, responses were coded for accuracy (0 = incorrect, 1 = correct) based on whether participants chose the proper statement from the particular pamphlet they read. As explained in the methods section, each participant saw four pamphlets total, two as negatively framed and two as positively framed. They responded to 16 statement recognition tasks (four statements in four pamphlets). These data were analyzed through a Generalized Getting the Message Across 16 Estimating Equation (GEE), which can be used for within-cluster correlations in regression models with binary outcomes. For this portion of the experiment, the GEE is an appropriate analysis because it takes into consideration that every subject was repeatedly measured on 16 trials, and these responses were binomially distributed. We also analyzed accuracy in a t-test against the value 0.5 so as to determine an effect that is significantly different from chance (50% accuracy). There was no significant difference in accuracy between the two age groups, ² (1, N = 784) = 1.746, ns. Of the 16 recognition tasks, younger adults chose the correct statement 64% of the time (SD = 0.03), as compared to older adults who were accurate 58% of the time (SD = 0.03). Positive statements were more accurately recognized than negative statements for all participants, ² (1, N = 784) = 29.286, p < .001. For trials where a positive statement should have been chosen, participants had an accuracy rate of 80% (SD = 0.02). When a negative statement should have been recognized, participants were accurate on 41.3% of the trials (SD = 0.03). There was a significant interaction between age and valence for accuracy of statement recognition, ² (1, N = 784) = 4.607, p < .05 (See Figure 4). Younger adults were more accurate in their positive statement recognition tasks (M = .78, SD = 0.03) than negative statement recognition tasks (M = .50, SD =0.05). For the negative statements, younger adults were at chance for accuracy, recognizing approximately half of the negative statements correctly t (191) = .000, ns. Their accuracy for recognizing positive statements was significantly higher than chance t (191) = 9.402, p < .001. Getting the Message Across 17 Older adults also were more accurate in recognizing positive statements (M = 0.83, SD = 0.03) than negative statements (M = 0.33, SD = 0.05). A one-sample t-test demonstrates that their accuracy for recognizing positive statements was significantly higher than a value of 0.5, t (199) = 12.066, p < .001. Interestingly, older adults’ accuracy for recognizing negative statements was significantly lower than chance (t (199) = -5.271, p < .001), indicating that for the negative recognition statements, older adults are not simply guessing. For a significant portion of statement recognition tasks in which older adults should have chosen the negative statement, they instead chose the positive statement that was never actually presented to them. Discussion For Study 1, our first hypothesis was rooted in socioemotional selectivity theory and the positivity effect, both of which suggest that older adults would be more influenced by positively framed messages in the personally salient healthcare domain. This hypothesis was partially supported by the results from Question 5, in that the frame of the pamphlet influenced participant’s reported informative value of each pamphlet. There were no significant interactions between age and pamphlet valence for the other four post-pamphlet questions. This combination of findings is meaningful in that the effect of frame does not seem to influence people’s opinions about particular health issues, however the frame does affect people’s more general evaluation of the information source. There are several potential explanations for why we did not find the expected result for the four questions that targeted attitudes and intended behaviors about each health domain. First, the manipulation might have simply not been sufficiently strong; the positive and negative statements may not have been powerful enough to alter participants’ attitudes about the healthcare issues. One challenge to choosing an experimental domain is that participants need to Getting the Message Across 18 care enough about the issue to pay attention to the information provided, however not be so invested in the issue that their opinions cannot be changed. We chose healthcare as a general domain to ensure that participants would have some personal interest in the information. In order to prevent any one domain as being too personally relevant to an individual participant, we included the four different health domains in the experiment. Although we attempted to find a balance between salience of issue and malleability of participant’s attitudes, this balance may have been too subtle, and as such, rendered our manipulation only partially successful. The pamphlets themselves did contain a significant amount of information, and this may have discouraged older adults from fully engaging in the task or thinking deeply about the healthcare issues presented. We attempted to account for this in our experimental design by counterbalancing the order and valence of pamphlets presented and giving participants an unlimited amount of time to read each pamphlet. Unfortunately, it is difficult to completely control for these potential confounds, which may have influenced our results. In addition, our 7point scale used to measure the outcome variables may not have been sensitive enough to detect the differences in manipulation. There were significant results in the statement recognition task. Older adults accuracy rates for positive and negative statement recognition were significantly higher and lower than chance, respectively. This result suggests that older adults have some bias or systematic distortion in the valence of information they recognize during a memory task. Younger adults had similar accuracy rates to the older adults for the positive statements. This overall positive bias may have been because the positive statements were easier to recognize, as several of the negatively framed statements included double-negative language emphasizing a behavior that avoided a loss. The strongest and perhaps most interesting result appears when comparing Getting the Message Across 19 younger and older adults on negative statement recognition. Younger adults had a 50% accuracy rate for the negative statements, which is what one would expect if participants were randomly guessing which of the statements they recognized. On the contrary, older adults had a 33% accuracy rate for the negative statements. This result indicates that on approximately 67% of the recognition trials where older adults should have chosen the negative statement, they responded that they saw the positive statement instead. If older adults were simply guessing or did not remember which statement they read, one could expect a 50% accuracy rate, similar to the younger adults. Our results, on the other hand, demonstrate that there is some bias in the information older adults are remembering or that they are distorting their memory for information in an increased positivity/reduced negativity manner. This interesting finding supports the positivity effect in a particular way. As has been noted in previous literature, one way to examine the positivity effect is by considering the ratio of positive to negative information recalled between older and younger adults (Charles, Mather, & Carstensen, 2003). In our study, both younger and older adults showed an overall bias in the positive direction, however the ratio of positive to negative messages recognized increased with age. We must note that while this result lends support for the positivity bias, our experimental design did not allow for more exact identification of the mechanism underlying this effect with older adults. Since the statement recognition task involved a forced-choice measure, we cannot determine if older adults were avoiding the negative statements in favor of the positive (i.e. decreased negativity bias), or if they were actually distorting their memories for the statements (i.e. increased false positive memories). Nevertheless, this finding is important for research examining how to best present healthcare information to older adults because they often rely on their memory when making a medical decision. It is rare for people to gather information about Getting the Message Across 20 a health issue or the risks and benefits of a treatment, and then immediately make a decision regarding that issue. Therefore, this research is significant because it demonstrates that it is not necessarily older adults’ immediate impressions of a health issue that is important, but instead what information they remember when making a later decision. There were a few unexpected results from Study 1, which fostered ideas for follow-up studies and future experiments. Personal history appears to have a large impact on how people evaluate a health issue, and this effect operates in an opposing manner between older and younger adults. For older adults with a history of an illness, they responded with higher scores (as compared to older adults without a history) to questions that targeted intentions to perform health behaviors and the informative value of the pamphlet. On the contrary, younger adults with a history of illness or disease reported lower scores to these questions than younger adults without a history. This interesting effect suggests that older adults who have experienced an illness become more aware of its seriousness and act with proactive health behaviors. Younger adults with a history of the illness instead appear to downplay its seriousness, believing that it is unimportant to proactively avoid the illness in the future. These results match with the concepts of adolescent invulnerability (Lapsley, 1993), where perhaps these younger adults who have experienced an illness feel more confident about their future vulnerability. Another unanticipated finding from this study is that older adults rated the pamphlets with positively-framed messages as more informative than those with negatively-framed messages. It seemed that when judging the overall informative value of the pamphlet, older adults again demonstrated a positive bias. In real-world situations, older adults often take advice or guidance regarding healthcare decisions from their physicians. Throughout these interactions, older adults are presumably making evaluations and judgments about their physician’s Getting the Message Across 21 competence and persuasiveness, similar to the construct targeted by Question 5 in Study 1. If older adults are evaluating a pamphlet as more informative because it contains more positive statements, would this effect manifest itself in older adults’ evaluations of their physicians? Study 2 Study 2 sought to further explore the relationship between positive pamphlets and their perceived informative value. However, we wanted to replicate this finding in a more social context. Physicians are a much more naturalistic healthcare information source for older adults than health pamphlets. One study found that 75% of people aged 65 and older stated that they would first seek out their personal healthcare provider when searching for information about cancer (Hesse, Nelson, Kreps, Croyle, Arora, Rimer, et al., 2005). Other research suggests that older adults form social impressions differently than younger adults. Specifically, older adults are better able to discriminate between the more and less informative aspects of individuals’ behaviors (Hess & Auman, 2001; Leclerc & Hess, 2007). These studies support the idea that increased age reflects an increase of social expertise resulting from the accumulation of social experiences, which would certainly play a role in older adults’ judgments of their physicians. Considering that socioemotional selectivity theory is based on people’s motivation to pursue emotionally-meaningful experiences and emotional satisfaction as they age, perhaps older adults would place more value on a physician who carries a positive, optimistic attitude versus a negative attitude. This question is important to examine because patient-physician communication is a critical aspect of older adults’ health. Understanding the mechanisms that influence how older adults evaluate their physicians has implications for patient satisfaction and adherence to treatments. Exploring from the results of Study 1, the purpose of Study 2 was to further understand how positive and negative information influences older adults’ attitudes and Getting the Message Across 22 impressions in a more social, less cognitively complex task. We hypothesized that older adults would rate physicians who provide health advice using positively-framed statements as more informative and persuasive than physicians who use negatively-framed statements. Method Participants Seventy-eight older adults ranging from 61 to 90 years of age (M = 74.25 years, SD = 7.35 years; 48 females & 30 males) and eighty younger adults ranging from 18 to 23 years of age (M = 19.86 years; SD = 1.16 years; 55 females & 25 males) participated in this experiment. Older adults were recruited from the Ithaca, NY community and were compensated $10 for their participation. Younger adults were recruited from Cornell University and received course credit for their participation. Measures We developed a short questionnaire that provided brief dialogues from four different doctors, each addressing a different health domain. We chose four common last names to create the physicians’ names (Smith, Williams, Jones, and Miller). Each doctor, however, was only referred to as “Dr. ______” in order to avoid any suggestion of the doctor’s gender. For continuity purposes, the four health domains chosen were the same as in Study 1: influenza, cholesterol, skin cancer, and sexually transmitted diseases. The brief dialogues from each doctor were composed of the same four positive or negative statements used in the pamphlets from Study 1. The statements were slightly modified grammatically to make the dialogue seem as if were spoken to the participant. (See Appendix B for an example of a positive-physician vignette). Getting the Message Across 23 This measure also included a questionnaire following each physician vignette. The questionnaire asked participants to rate on a ten point Likert-type scale their impressions about how informed and persuasive they believed the physician to be. For continuity, we also included questions from Study 1 regarding participants’ attitudes and beliefs about the healthcare issue (See Appendix C). In Study 1, the majority of participants rated their opinions about the healthcare issues on the higher end of the scale, many within the 5, 6, and 7 range. This trend may have been one of the reasons for few significant effects in Study 1; participants’ ratings, regardless of the pamphlet valence, were very close together. In Study 2, we chose to use a ten point scale in hopes that a larger scale would make the effects of valence easier to distinguish. Procedure This portion of the study involved a 2 (age) X 2 (valence) between-subjects design. Participants were randomly assigned to either the positive or negative condition and received the corresponding questionnaire. After reading the instructions page, participants were given the opportunity to ask the experimenter any questions before proceeding to the actual questionnaire. Each questionnaire contained the brief physician dialogue and attitude/opinion questions for all four healthcare domains. The order of these domains was randomized as each packet was assembled. At the end of the questionnaire, participants indicated “yes” or “no” to whether they had participated in our previous pamphlet study (Study 1). The amount of time required to complete this questionnaire was approximately 15 minutes. Results For the purposes of this study, the main interest focused on examining how valence influenced participants’ impressions of how informed and persuasive they believed their physician to be. Therefore, the analyses only included the questions that targeted these specific Getting the Message Across 24 factors. The analysis conducted was a mixed-model ANOVA, because each participant had ratings for four different doctors; this analysis designates age and valence as fixed variables and subject as a random variable. Additionally, a composite variable was developed to identify the overall impression of the physician. Question 1 targeted how informed participants believed the physician to be, while Question 2 asked how persuasive the physician was in the vignette. The reliability between these two variables was very high (Chronbach’s alpha = 0.89), therefore the analyses could collapse responses to these questions within each physician vignette. There was a main effect of age on the participants’ ratings of the composite variable, F (1, 153) = 10.62, p < .05. Older adults overall rated physicians as more informed and persuasive (M = 7.05, SD = 0.17) than the younger adults did (M = 6.26, SD = 0.17). However, there was no effect of physician valence on the participants’ composite evaluations of the physicians (F (1, 153) = 2.75, ns). There was no significant interaction between age and valence for participants’ ratings on the composite informed/persuasive variable, F (1, 153) = 1.57, ns. Participant ratings did trend in the predicted direction, with older adults rating positive physicians as higher (M = 7.43, SD = 0.24) than the negative physicians (M = 6.67, SD = 0.24). Younger adults did not appear to differ in their evaluations between positive physicians (M = 6.31, SD = 0.24) and negative physicians (M = 6.21, SD = 0.24). To explore this result further, we analyzed the specific pairwise comparison between positive and negative physicians within only the older adult group, which was marginally significant, F (1, 75.28) = 3.36, p = .07 (positive physician, M = 7.43, SD = 0.24; negative physician, M = 6.67, SD = 0.24) (See Figure 5). Discussion Study 2 sought to expand a finding from Study 1, in which valence influenced older adults’ evaluations of the informative value of a particular source. In Study 1, this health Getting the Message Across 25 information source was a pamphlet, whereas Study 2 used a physician as the source for health information. We did not find a statistically significant difference between older adults’ ratings of physicians based on the valence of the vignette. These ratings did trend in the predicted direction, and perhaps with a larger sample size, the effect would become significant. Younger adults, on the other hand, did not appear to be influenced by physician valence when evaluating the persuasiveness and informative value of a physician. These results suggest that there is some change as people age in the ways that they evaluate their physicians. Within the older adult group, this effect appears to be influenced by the positive or negative tone of the physician. General Discussion These studies examined the strength of positively and negatively framed information as an influence on older and younger adults’ opinions, attitudes, and memory for particular health issues. Previous literature on typical framing effects and the positivity bias in old age indicate two conflicting predictions regarding information presentation to older adults. Goal-framing research has shown that negative frames more strongly influence people in regards to proactive health behavior and opinions. The positivity effect, on the other hand, theorizes that processing emotional information changes with age, and older adults seek out positive information and remember it better than negative information. Within the goal-framing literature, no studies to our knowledge have used age-specific populations, and the existing research examining aging and framing have used only risky-choice paradigms. This study attempted to distinguish between these opposing predictions and add to existing knowledge in the aging and decisionmaking field in an area that has not been previously investigated. It is important to note that this research project was relatively exploratory in nature. Both the framing and positivity effect literature recognize that the effects can be subtle or easily influenced by a variety of factors. Getting the Message Across 26 Research on persuasion even suggests that time of day can have a strong influence on whether older adults implement a central or peripheral processing strategy (Yoon, Lee, & Danziger, 2007). Central and peripheral processing are inherently different processing strategies, with one focusing on the content of the information and the other on superficial factors, respectively. This finding by Yoon, Lee and Danziger (2007) demonstrates that older adult decision-making can be easily affected by seemingly trivial factors, such as time of day. The field of cognitive and emotive processing with older adults contains complex and sensitive processes that are still not fully understood. This research, however, hopes to contribute to the field by testing theories in a practical context that easily applies and translates into the healthcare domain. There are several major strengths to Study 1, including the experimental design and various controlled factors. The positive and negative pamphlets were very comparable, as they used the exact same physical design and color scheme, and they contained the same bulleted lists of information about the healthcare issue. The only areas that differed between the pamphlets were the four framed statements, which were bolded in both the positive and negative pamphlets. This equivalence allowed us to conclude that any differences in outcome variables from Study 1 were due to differences in pamphlet valence and not other uncontrolled factors. Another strength of this study is that it implemented several different healthcare domains. It is probable that healthcare issues are a more salient topic to older adults in general. However, by using a variety of health issues, we eliminated the potential confounds of one highly salient domain (e.g., skin cancer) or one less significant domain (e.g., sexually transmitted diseases). The pamphlets themselves appeared similar to pamphlets found in a physician’s office, and they contained health information from a national health database. These factors lend support to the ecological validity of this study. Although it would be nearly impossible to evoke Getting the Message Across 27 the same emotional response in participants as if they were in an actual healthcare setting, the pamphlets looked relatively realistic and presumably induced some genuine emotions and thoughts about the presented healthcare issues. Additionally, most previous studies of the positivity effect have used stimuli such as emotional pictures (Charles, Mather, & Carstensen, 2003; Mikels, Larkin, Reuter-Lorenz, & Carstensen, 2005) or faces (Mather & Carstensen, 2005). Our experiment tested the positivity effect using pamphlets and valenced healthcare messages, a realistic and practical medium that is easily translated into the healthcare domain. Another major strength regarding the relationship between Study 1 and Study 2 lies in the comparability of the valenced statements. The vignettes in Study 2 contained the same statements used in the pamphlets and statement recognition task of Study 1. In this sense, we were able to transform Study 1 into Study 2 by essentially personifying the pamphlets, targeting the social aspects of information processing between older and younger adults. Additionally, altering the scale from Study 1 to Study 2 allowed clearer observation of the effects on outcome measures. In Study 1, a majority of participants chose ratings on the higher end of the 7-point scale. The marginally significant results from Study 2 (which used a ten-point scale) suggest that a larger scale would have been useful in Study 1. Lastly, considering the experimental design of the Study 1, it was beneficial to implement valence as a within-subjects factor across several different domains. This design compensated for our small number of participants by enhancing the power in our analyses. One limitation of Study 1 is that it used a relatively small subject pool from a homogeneous convenience sample. Although we tried to offset the effects of a small sample by implementing a within-subjects factor, the limited number of participants potentially contributed to the insignificant results from Study 1. It is possible that a larger sample would detect the Getting the Message Across 28 predicted differences between age groups and responses to emotionally positive or negative healthcare information. Additionally, we only used one question per construct in the postpamphlet measures, which made it difficult to ensure construct validity or improve statistical power in these responses. This experiment examined people’s immediate opinions of health issues and intended behaviors, however to enhance the ecological validity of the studies, it would be important to observe peoples’ actual behaviors. Future studies expanding on this experiment would benefit from a longitudinal design for several reasons. First, it would be important to follow up with participants’ actual behaviors, for example observing if people actually wore sunscreen more frequently after reading a skin cancer pamphlet. Second, the memory task from Study 1 demonstrated a bias in the type of information that older adults remembered, however this delay was approximately 15 minutes long. To gain a better understanding of the pervasiveness of this effect, it would be important to conduct memory tasks with the participants days, weeks, or even months later. This extended duration of “delayed decision-making” is more realistic considering the time frame when people are presented information and when they must recall the same information to make a health-related decision. These studies present a new perspective on how older and younger adults differ in their emotional processing as it relates to health related decisions and perceptions. The effectiveness of providing healthcare information to older adults can vary based on several factors, including health domain, personal history, and the emotional tone of the information source. Our results demonstrate that emotion plays a role in the type of information that older adults remember, indicating that positively-framed healthcare information may have stronger long-term effectiveness than negatively-framed messages. Lastly, these trends can have applications in Getting the Message Across broader health contexts, including patient-physician communication, the patient-physician relationship, and other concepts in the emerging field of patient-centered medicine (Stewart, Brown, Weston, McWhinney, McWilliam, & Freeman, 2003). With the increasing older population, these topics become even more important to consider. It is critical to better understand how older adults view and process health issues so that we can provide them the optimal information for their important health-related decisions. 29 Getting the Message Across 30 References Block, L. & Keller, P. A. (1995). When to accentuate the negative: The effects of perceived efficacy and message framing on intentions to perform a health-related behavior. Journal of Marketing Research, 32, 192–203. Carstensen, L. L., Isaacowitz, D. M., & Charles, S. T. (1999). Taking time seriously: A theory of socioemotional selectivity theory. American Psychologist, 54, 165-181. Carstensen, L. L., & Mikels, J. A. (2005). At the intersection of emotion and cognition: Aging and the positivity effect. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 14(3), 117-121. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2007, November 8). Cholesterol. Retrieved February 3, 2009, from http://www.cdc.gov/Cholesterol/index.htm. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2008, July 16). Key Facts About Seasonal Influenza (Flu). Retrieved February 3, 2009, from http://www.cdc.gov/flu/keyfacts.htm. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2008, November 24). Basic Information About Skin Cancer. Retrieved February 3, 2009, from http://www.cdc.gov/cancer/skin/basic_info/. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2008, November 24). STD-Health CommunicationFact Sheets. Retrieved February 3, 2009, from http://www.cdc.gov/std/healthcomm/fact_sheets.htm. Charles, S. T., Mather, M, & Carstensen, L. L. (2003). Aging and emotional memory: The forgettable nature of negative images for older adults. Journal of Experimental Psychology, 132(2), 310-324. Fernandes, M., Ross, M., Wiegand, M., & Schryer, E. (2008). Are the memories of older adults positively biased? Psychology and Aging, 23(2), 297-306. Getting the Message Across 31 Hess, T. M., & Auman, C. (2001). Aging and social expertise: The impact of trait-diagnostic information on impressions of others. Psychology and Aging, 16, 497–510. Hesse, B.W., Nelson, D.E., Kreps, G.L., Croyle, R.T., Arora, N.K., Rimer, B.K., et al. (2005). Trust and sources of health information: The impact of the Internet and its implications for health care providers: Findings from the first Health Information National Trends Survey. Archives of Internal Medicine, 165(22), 2618-2624. Kennedy, Q., Mather, M, & Carstensen, L. (2004). The role of motivation in the age-related positivity effect in autobiographical memory. Psychological Science, 15(3), 208-214. Kim, S., Goldstein, D., Hasher, L. & Zacks, R. T. (2005). Framing effects in younger and older adults. J. Gerontol. B. Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci., 60, 215-218. Lapsley, D. K. (1993). Towards an integrated theory of adolescent ego development: The "new look" at adolescent egocentricism. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 63, 562-571. Leclerc, C. M., & Hess, T. M. (2007). Age differences in the bases for social judgments: Tests of a social expertise perspective. Experimental Aging Research, 33(1), 95-120. Levin, I. P., Schneider, S. L., & Gaeth, G. J. (1998). All frames are not created equal: A typology and critical analysis of framing effects. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 76, 149-188. Maheswaran, D. & Meyers-Levy, J. (1990). The influence of message framing and issue involvement. Journal of Marketing Research, 27, 361–67. Mather, M. & Carstensen, L. L. (2005). Aging and attentional biases for emotional faces. Psychological Science, 14(5), 409-415. Getting the Message Across 32 Mayhorn, C. B., Fisk, A. D., & Whittle, J. D. (2002). Decisions, decision: Analysis of age, cohort, and time of testing on framing risky decision options. Human Factors, 44(4), 515-521. Meyerowitz, B. E. & Chaiken, S. (1987). The effect of message framing on breast selfexamination attitudes, intentions, and behavior. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 52, 500-510. Mikels, J. A., Larkin, G. R., Reuter-Lorenz, P. A., & Cartensen, L. L. (2005). Divergent trajectories in the aging mind: Changes in working memory for affective versus visual information with age. Psychology and Aging, 20(4), 542-553. Mikels, J. A., Reed, A. E. (in press). Monetary losses do not loom large for older adults: Evidence for a more balanced framing effect in older adults. Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences. Rothman, A. J., Salovey, P., Antone, C., Keough, K., & Martin, C. D. (1993). The influence of message framing on intentions to perform health behaviors. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 29, 408-433. Stewart, M., Brown, J. B., Weston, W. W., McWhinney, I. R., McWilliam, C. L., & Freeman, T. R. (2003). Patient-centered medicine: Transforming the clinical method. (2nd ed.). Oxon, United Kingdom: Radcliffe Publishing. Tversky, A. & Kahneman, D. (1981). The framing of decisions and psychology of choice. Science, 211, 453-458. Yoon, C., Lee, M. P., & Danziger, S. (2007). The effects of optimal time of day on persuasion processes in older adults. Psychology and Marketing, 24(5), 475-495. Getting the Message Across 33 Author Note I would like to thank Dr. Joseph Mikels for his guidance and encouragement with this project. I would also like to thank Dr. Marianella Casasola and Andrew Reed for their support and feedback throughout the course of the entire research process. This research was conducted as fulfillment of the undergraduate honors program. Partial funding was provided by the Human Ecology Alumni Association Student Grant, College of Human Ecology, Cornell University. Correspondence concerning this article should be addressed to Andrea M. Shamaskin, Department of Human Development, Cornell University, Ithaca, NY 14850. Email: [ams357@cornell.edu] Getting the Message Across Appendix A Question 1: Do you think influenza is a serious health problem? ─−1─−2─−3─−4─−5─−6─−7─− Not at all Extremely Question 2: What do you think is your likelihood of contracting influenza? ─−1─−2─−3─−4─−5─−6─−7─− Not at all Extremely Question 3: How likely are you to get the influenza vaccine and practice preventative behaviors? ─−1─−2─−3─−4─−5─−6─−7─− Not at all Extremely Question 4: How likely are you to see your doctor if you notice symptoms of influenza? ─−1─−2─−3─−4─−5─−6─−7─− Not at all Extremely Question 5: How informative was this pamphlet? ─−1─−2─−3─−4─−5─−6─−7─− Not at all Extremely Concepts intended to measure per question: Question 1: Attitude toward health issue Question 2: Perceived vulnerability Question 3: Intention to perform preventative behaviors Question 4: Intention to perform detection behaviors Question 5: Informative value of pamphlet 34 Getting the Message Across 35 Appendix B Imagine you are meeting with a new doctor, Dr. Smith, to talk about a cholesterol issue. Dr. Smith tells you: By asking me about your cholesterol levels, you can take a proactive approach to regulating your overall health. Research shows that people who are aware of their cholesterol levels have an increased chance of recognizing their risks for other related health issues. By watching your diet and exercising regularly, you can maintain control over your cholesterol levels. You can gain several potential health benefits by practicing healthy lifestyle behaviors. Take advantage of this opportunity. Getting the Message Across 36 Appendix C Please read the following questions and CIRCLE your number choice on the scale. After meeting with Dr. Smith, how informed do you think Dr. Smith is about cholesterol? 1--------2--------3--------4--------5--------6--------7--------8--------9--------10 Dr. Smith knows nothing about cholesterol Dr. Smith is the leading expert on cholesterol How persuasive do you find Dr. Smith? 1--------2--------3--------4--------5--------6--------7--------8--------9--------10 Not at all persuasive Extremely persuasive Do you think cholesterol is a serious health problem? 1--------2--------3--------4--------5--------6--------7--------8--------9--------10 Not at all Extremely What do you think is your likelihood of developing high cholesterol? 1--------2--------3--------4--------5--------6--------7--------8--------9--------10 Not at all likely Extremely likely How likely are you to change your diet or amount of exercise in order to adjust your risks for high cholesterol? 1--------2--------3--------4--------5--------6--------7--------8--------9--------10 Not at all likely Extremely likely How likely are you to get a blood test in order to check for high cholesterol? 1--------2--------3--------4--------5--------6--------7--------8--------9--------10 Not at all likely Extremely likely Getting the Message Across 37 Table 1 Responses to post-pamphlet questions by age group Older Adult Mean (SD) Younger Adult Mean (SD) Question 1 5.21 (0.16) 4.38 (0.16) F (1, 45) = 10.61, p < .01* Question 2 3.59 (0.17) 3.67 (0.17) F (1, 45) = 0.12, ns Question 3 5.75 (0.24) 4.48 (0.25) F (1, 45) = 13.51, p < .01* Question 4 4.89 (0.22) 4.30 (0.23) F (1, 45) = 3.41, ns Question 5 5.68 (0.28) 4.28 (0.29) F (1, 45) = 12.38, p < .01* The rightmost column presents results from a mixed model Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) * p < .01. Getting the Message Across 38 Table 2 Responses to post-pamphlet questions by health domain Influenza Cholesterol Skin Cancer 6.00 (.19) Sexually Transmitted Diseases 6.08 (.19) Question 1 4.75 (.19) 5.83 (.19) F (3,135) = 17.55 * Question 2 3.96 (.21) 3.92 (.21) 2.19 (.21) 4.44 (.27) F (3,135) = 25.1 * Question 3 4.55 (.26) 4.81 (.26) 5.89 (.26) 5.21 (.26) F (3, 135) = 6.51 * Question 4 4.86 (.25) 5.30 (.25) 3.42 (.25) 4.82 (.25) F (3, 135) = 13.86 * Question 5 4.70 (.22) 5.21 (.22) 4.83 (.22) 5.17 (.22) F (3, 135) = 4.58 * The rightmost column presents results from a mixed model Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) * p < .01. Getting the Message Across 39 Table 3 Responses to post-pamphlet questions by age and personal history OA-history Mean (SD) OA-no history Mean (SD) YA-history Mean (SD) YA-no history Mean (SD) Question 1 5.85 (.27) 6.26 (.25) 3.66 (.35) 5.48 (.22) F (1, 144.9) = 11.35* Question 2 4.47 (.27) 2.85 (.28) 4.52 (.41) 3.48 (.18) F (1, 167.7) = 1.05 Question 3 6.02 (.35) 5.49 (.31) 3.34 (.48) 4.72 (.26) F (1, 153.7) = 9.26* Question 4 5.52 (.35) 4.29 (.30) 3.87 (.51) 4.42 (.25) F (1, 160.9) = 6.67* Question 5 5.84 (.32) 5.61 (.31) 3.52 (.35) 4.42 (.29) F (1, 136.4) = 12.50* Note: OA = Older adult, YA = Younger adult The rightmost column presents results from a mixed model Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) * p < .05. Getting the Message Across Figure Captions Figure 1. Pamphlet design of positive Skin Cancer pamphlet. Figure 2. Pamphlet design of negative Skin Cancer pamphlet. Figure 3. Response to Question 5 by Age and Valence. Figure 4. Accuracy on memory recognition task by Age and Valence. The dashed line represents an “at-chance” accuracy rate. Figure 5. Participant ratings on physician informed/persuasive score by Age and Valence. 40 Getting the Message Across Figure 1. 41 Getting the Message Across Figure 2. 42 Getting the Message Across Figure 3. Valence Neg Pos Mean Q5 6 4 6 5.34 4.229 2 0 Older Younger Age Error bars: +/- 1 SE 4.292 43 Getting the Message Across Figure 4. 44 Getting the Message Across Figure 5. 45