www

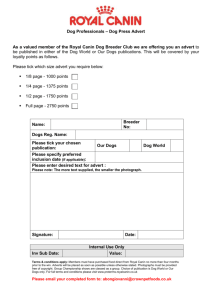

advertisement