Lect. univ. drd. Elena Butoescu

advertisement

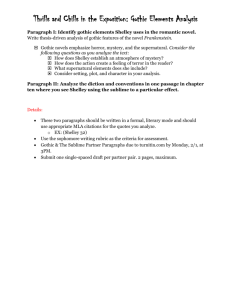

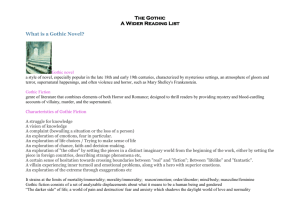

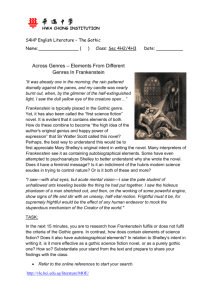

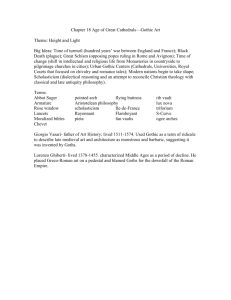

Curs practic Interpretari de texte, an II ID Lect. univ. drd. Elena Butoescu Curs V The Romantic Gothic Novel. Narrative voice and Setting: Mary Shelley – Frankenstein Introduction into the Gothic Novel About the turn of the eighteenth century there appeared the novels of “mystery and imagination”, also called Gothic Novels. The term Gothic is primarily an architectural one, denoting that kind of European building which flourished in the Middle Ages and showed the influence of neither the Greeks nor the Romans. Gothic architecture, with its pointed arches, began to come back to England in the middle of the 18th century. This kind of building suggested mystery, romance, revolt against classical order, wildness, through its associations with mediaeval ruins - ivy-covered, haunted by owls, washed by moonlight, shadowy, and mysterious. “Gothic” is a word which has a wide variety of meanings, and which has had in the past even more. It is used in a number of different fields: as a literary term, as a historical term, as an architectural term, or as an artistic term. And as a literary term in contemporary usage, it has a range of different applications. When thinking of the Gothic novel, a set of characteristics springs readily to mind: an emphasis on portraying the terrifying, a common insistence on archaic settings, a prominent use of the supernatural, the presence of highly stereotyped characters and the perfect techniques of literary suspense are the most significant. Used in this sense, “Gothic” fiction is the fiction of the haunted castle, of heroines preyed on by unspeakable terrors, of ghosts, vampires, monsters and werewolves, of spectres, demons, corpses, skeletons, evil aristocrats, monks and nuns. These figures populate the 18th century Gothic landscapes. This list grew, in the 18th century, with the addition of scientists, fathers, husbands, madmen, criminals and the monstrous double signifying duplicity and evil nature. Gothic novels were usually set in the past and in foreign countries, particularly the Catholic countries of southern Europe. In the 18th century, the major locus of Gothic plots was the castle, which was linked to other medieval edifices - monasteries, churches, and graveyards. They symbolized a feudal past associated with barbarity, superstition and fear. In the 19th century, the city became the site of nocturnal corruption, violence, and decadence, a locus of real horror. The original meaning of the word “Gothic” was literally “to do with the Goths” or with the barbarian northern tribes who played a part in the collapse of the Roman Empire. The 17th and early 18th century writers who used the term in this sense had very little idea of who the Goths were or what they were like. One thing that was known was that they came from northern Europe, and thus the term had a tendency to broaden out, to become virtually a synonym for “Teutonic” or “Germanic”, while retaining its connotations of barbarity. “Gothic” became descriptive of things medieval; if “Gothic” meant to do with the medieval world, it followed that it was a term which could be used in opposition to “classical”, as it can be seen in Fred Botting's “Gothic, the new critical idiom”. The classical was well-ordered while the Gothic was chaotic; the classical was simple and pure while Gothic was ornated and convoluted. Where the classics offered a set of cultural models to be followed, Gothic represented excess and exaggeration, the product of the wild and the uncivilised. We ought to mention in this context a work produced later in the century - Frankenstein by Mary Shelley (1797-1851). This was written during a wet summer in Switzerland, when her husband (the poet P.B. Shelley) and Lord Byron were amusing themselves by writing ghost-stories and she herself was asked to compose one. She could never have guessed that her story of the scientist who makes an artificial man - by which he is eventually destroyed - would give a new word to the language and that its subject would rise from humble fiction to universal myth. Frankenstein is a morally probing exploration of responsibility and of the body of knowledge which we now call “science”. The tendency amongst Byron’s associates to push ideas to extremes, and to test sensation and experience, is here developed as a study of the consequences of experiment and of moving into the unknown. Like the legendary Prometheus, Frankenstein’s enterprise is punished, but not by heaven; his suffering is brought upon him by a challenge to his authority on the part of the creature that he has made. This artificial man, like the ruined, questioning Adam, turns to accuse his creator with an acute and trained intelligence. The novel ends where it began in a wild and frozen polar landscape, a wasteland which both purges and purifies the human aberrations represented by Frankenstein and his flawed experiment. Gothic literature was seen as a challenge to rationality. Gothic deals with passion. Reason has nothing to do with passion. Good depends on evil, light on darkness, reason on irrationality, in order to define limits. Gothic literature also deals with a very relevant element, which is fear. Fear is not merely a theme or an attitude, it also has consequences in terms of form, style and the social relations of the texts; and exploring Gothic is also exploring fear and seeing the various ways in which terror breaks through the surfaces of literature, differently in every case, but also establishing for itself certain distinct continuities of language and symbol. Gothic fiction was popular with a new reading public which was itself predominantly bourgeois – popular, in fact, with a middle class who had only twenty years earlier been reading a vastly different kind of novel. Horace Walpole (1717-1797) set the example of a Gothic novel in 1764 by The Castle of Otranto, which is a melodramatic curiosity. He was followed by Ann Radcliffe's The Romance of the Forest, The Mysteries of Udolpho and The Italian. They are skilfully written and Radcliffe's mysteries always have a rational explanation at the end. Matthew Gregory Lewis (1775-1818) wrote The Monk, which is full of devils, horror, torture, perversions, magic, and murder. He owes much of his control of atmosphere and exploitation of suspense to Ann Radcliffe. But his attitude to the preternatural is different. He takes quite seriously magic mirrors, charmed herbs and conjurations of evil spirits. Such novels enjoyed a short-lived popularity but one cannot deny their power of expression. They both paved the way to the Romantic Movement. An excerpt from Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein or, the Modern Prometheus (published in 1818), Ch. 10 “[…] his stature also, as he approached, seemed to exceed that of man. I was troubled: a mist came over my eyes, and I felt a faintness seize me; but I was quickly restored by the cold gale of the mountains. I perceived, as the shape came nearer (sight tremendous and abhorred!) that it was the wretch whom I had created. I trembled with rage and horror, resolving to wait his approach, and then close with him in mortal combat. He approached; his countenance bespoke bitter anguish, combined with disdain and malignity, while its unearthly ugliness rendered it almost too horrible for human eyes. But I scarcely observed this; rage and hatred had at first deprived me of utterance, and I recovered only to overwhelm him with words expressive of furious detestation and contempt. ‘Devil,’ I exclaimed, ‘do you dare approach me? and do not you fear the fierce vengeance of my arm wreaked on your miserable head? Begone, vile insect! or rather, stay, that I may trample you to dust! and, oh! that I could, with the extinction of your miserable existence, restore those victims whom you have so diabolically murdered!’ ‘I expected this reception,’ said the dæmon. ‘All men hate the wretched; how, then, must I be hated, who am miserable beyond all living things! Yet you, my creator, detest and spurn me, thy creature, to whom thou art bound by ties only dissoluble by the annihilation of one of us. You purpose to kill me. How dare you sport thus with life? Do your duty towards me, and I will do mine towards you and the rest of mankind. If you will comply with my conditions, I will leave them and you at peace; but if you refuse, I will glut the maw of death, until it be satiated with the blood of your remaining friends.’ ‘Abhorred monster! fiend that thou art! the tortures of hell are too mild a vengeance for thy crimes. Wretched devil! you reproach me with your creation; come on, then, that I may extinguish the spark which I so negligently bestowed.’ My rage was without bounds; I sprang on him, impelled by all the feelings which can arm one being against the existence of another. He easily eluded me, and said‘Be calm! I entreat you to hear me, before you give vent to your hatred on my devoted head. Have I not suffered enough that you seek to increase my misery? Life, although it may only be an accumulation of anguish, is dear to me, and I will defend it. Remember, thou hast made me more powerful than thyself; mine height is superior to thine; my joints more supple. But I will not be tempted to set myself in opposition to thee. I am thy creature, and I will be even mild and docile to my natural lord and king, if thou wilt also perform thy part, the which thou owest me. Oh, Frankenstein, be not equitable to every other, and trample upon me alone, to whom thy justice, and even thy clemency and affection, is most due. Remember, that I am thy creature; I ought to be thy Adam; but I am rather the fallen angel, whom thou drivest from joy for no misdeed. Everywhere I see bliss, from which I alone am irrevocably excluded. I was benevolent and good; misery made me a fiend. Make me happy, and I shall again be virtuous.’ […] Ch. 20 ‘You have destroyed the work which you began; what is it that you intend? Do you dare to break your promise? I have endured toil and misery: I left Switzerland with you; I crept along the shores of the Rhine, among its willow islands, and over the summits of its hills. I have dwelt many months in the heaths of England, and among the deserts of Scotland. I have endured incalculable fatigue, and cold, and hunger; do you dare destroy my hopes?’ ‘Begone! I do break my promise; never will I create another like yourself, equal in deformity and wickedness.’” Task: 1. The passages you have read are examples of first person narrative. Find references in the narrative to Victor Frankenstein’s character, passionate nature, and unconventional education. 2. What kind of atmosphere does the description of the setting create? 3. Describe the dialogue between Victor Frankenstein and the monster. Compare their states of mind.