To Participate or not to Participate?: An Analysis of Hispanic Political

advertisement

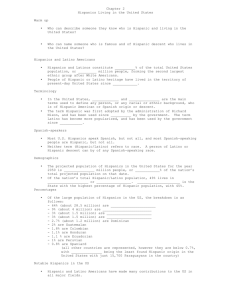

To Participate or not to Participate?: An Analysis of Hispanic Political Participation Janine Marie Moreno Creighton University Moreno 2 I. INTRODUCTION While various researchers have studied differences in participation levels between African-Americans and Anglos, the evidence has traditionally been limited. It fails to address minorities other than African-Americans and assumes that the evidence for African-Americans is spread equally amongst all groups of ethnicity. This paper addresses the differences between Hispanics and their roles in political participation. Specifically this paper focuses on Hispanics within American politics. There is substantial research literature that examines and tries to explain rates and modes of political participation (Bennett and Bennett 1989, 123; Milbrath and Goel 1977, 126). Yet the knowledge base for Hispanic political participation is practically non-existent. Since there is a lack of theories regarding Hispanic political participation researchers rely primarily on African-American theories. This, however, presents a problem. Linking African-American theories to Hispanic participation neglects that both of these minority groups are very diverse. African Americans and Hispanics fight for much different causes. African- Americans, for instance, are notorious for participating in politics more than Hispanics. A strong reason for this is African-Americans long history of segregation and inequality, in which the need and desire to overcome barriers in the American political system is pressing. Hispanics, which now constitute more than 30 percent of the population in California and Texas, will eventually grow to become the majority of the American population. Yet, despite their numbers Hispanics in the United States have not received much attention in political science research, and there has been little effort to bring together the implications of the analyses that do exist. Moreno 3 Understanding Hispanic politics in the United States is indeed a challenge. First, there is much diversity within the Hispanic community. Mexican Americans, Puerto Ricans, and Cubans are some examples of different subgroups within the Hispanic community. Second, the very large increase in the total number of Hispanics makes it more difficult to differentiate the characteristics that separate these subgroups. Research Question: Therefore this paper examines why do some Hispanics participate in politics more than others? Verba and Nie’s strong case of socioeconomic status theory has proven overtime to be the widely acceptable conclusion to this question. However, there is a unique contradiction. Hypothesis: In Garcia and Arce’s analysis regarding Hispanics’ roles in political participation, they found that Hispanics with lower economic status and with lower educational-attainment have higher levels of civic orientation. This paper, therefore, hypothesizes that Hispanics with lower socioeconomic status are more likely to participate in politics. With the significant increase of Hispanics within the last decade there is more empirical data available to use than in past years. Further, there is a growing concern about the political potential of Hispanics and how their political involvement is impacting the American political system (Garcia 1988, 44). Since, there has been very little research done on Hispanic political participation this paper focuses primarily on Hispanic’s political participation. Moreno 4 II. SIGNIFICANCE OF THE QUESTION Hispanics are in a disadvantaged position politically, socially, and economically in the United States (Hero 1992, 11). Political scientists are concerned with why Hispanics fare considerably less well than Anglos, and less well in some instances than blacks on a variety of measures of political representation and socioeconomic status (Hero 1992, 12). Indeed, the discussion of political participation in America has been grounded in theoretical discussions of democracy involving individual rights, responsibilities, and institutional responsiveness and policies (Garcia 1988, 44). In academic discussion experts are concerned with the differences between minorities, and the differences between the social classes. Experts utilize reason to evaluate these differences and form theories. For instance, the primary theory of political participation is the infamous socioeconomic status (SES) theory, with its derivative most often linked to researcher’s Verba and Nie. Many scholars claim that socioeconomic status is often cited as the primary factor accounting for variations in rates of political participation across the racial and ethnic groups (Leighley and Nagler 1992a, 1992b; Verba and Nie 1972; Verba, Scholozman, and Brady 1995; Wolfinger and Rosenstone 1980). However, scholars of minority politics investigate a wider range of theories of participation further than socioeconomic status. Cultural factors and value systems are just some of the salient contributors to participatory patterns in minority political participation (McClain and Garcia 1993, 535; Verba 1993, 536). Further, politicians and policy makers enact a major role in minority political participation. For example, the current 2004 presidential campaign is a great example of Moreno 5 two candidates stressing the importance of conquering the minority vote. Both President Bush and Senator Kerry strongly urged minorities to go to the polls and break the historical political barriers, and to overcome the lack of political participation. For the purpose of politics, dominant interpretations of U.S politics hold that if citizens exercise the right to vote and participate in politics in other ways, the system can be responsive to their concerns and preferences (Hero 1992, 67). As indicated earlier, the research on reasons for political participation by Hispanics is very limited. The discussion in this study about Hispanic political participation represents the extant literature and major findings mentioned below. III. LITERATURE REVIEW In Jan Leighley and Arnold Vedlitz’s analysis of minority political participation entitled “Race, Ethnicity, and Political Participation: Competing Models and Contrasting Explanations,” they demonstrate five models derived from various scholars. Socioeconomic Status, Psychological Resources, Social Connectedness, Group Consciousness, and Group Conflict are the five theories tested across four racial ethnic groups (Leighley and Vedlitz 1999, 1092). Both Leighley and Vedlitz examine why there are differences with political participation among the four minority groups being tested. For the purpose of this study, this paper only examines the Hispanic political participation findings and conclusions involved in Leighley and Vedlitz analysis. The data used in this analysis to test these theories are drawn from a statewide public opinion survey in Texas, the second most populous state in the nation, and also the most ethnically diverse (Leighley and Vedlitz 1999, 1093). (Leighley and Vedlitz 1999, Moreno 6 1100) describe the empirical measures they use to test the five participation models. The socioeconomic status model is tested using two standard demographic indicators: Education and Income. The Psychological Resources model is operationalized using two indicators: Political Interest, and Political Efficacy. The Social Connectedness model is tested using three indicators: Marital Status, Length of Residence, and Home Ownership. The Group Consciousness model consists of two variables: Group Closeness and Intergroup Distance. Finally, the group conflict model is conceptualized as the potential threat from out-groups. Leighley and Vedlitz’s findings are that the Socioeconomic Status, Psychological Resource, and Social Connectedness models receive strong support as predictors of overall participation for Hispanics (Leighley and Vedlitz 1999, 1110). Leighley and Vedlitz conclude that Hispanics with higher levels of status or Psychological Resources (e.g., Political Efficacy) participate more. In contrast, their findings with Group Conflict and Group Consciousness did not support the overall participation for Hispanics. Socioeconomic Status Theory Leighley and Vedlitz are not the first researchers to confirm the SES theory. Verba and Nie (1972, 29), for instance, were among the first researchers to establish the socioeconomic status theory as an explanation of mass political behavior: individuals with high levels of socioeconomic resources (e.g., education and income) are more likely to adopt psychological orientations that motivate their participation in the political system (Verba and Nie 1972, 32). Many other studies also confirm their findings of higher levels of education, income, and occupational status tend to vote more, contact more, organize more, and campaign more than do those with lower status Moreno 7 (Conway 1991; Kenny 1992; Leighley 1990; Leighley and Nagler 1992a, 1992b; Nie et al. 1988; Verba et al. 1993, 1995; see also Leighley 1995 for a review of those studies). In Carole Ulaner, Bruce Cain, and D. Roderick Kiewiet analysis of political participation, entitled “Political Participation of Ethnic minorities in the 1980’s,” they demonstrate that demographic and economic variables such as age, income, level of education, marital status, incidence of single parenting, employment, and home ownership affect political participation. They claim that such effects explain the lack of socioeconomic resources (as in the case for Hispanics and blacks) (Uhlaner, Cain, and Kiewiet 1989, 195). Moreover, Ulaner, Cain, and Kiewiet add a unique variable: being a single mother is indicative of the absence of free time as well as income. The results, however, show that being a single mother does not have much significance relative to political participation. In addition to the demographic and economic variables, they consider the effects of ethnic minority political participation as an explicit sense of group selfidentification (Ulaner, Cain, and Kiewiet 1989, 197). Their conclusions demonstrate that if the Hispanic population ages and becomes more Americanized and more English speaking, and if the education and income levels rise, then they expect to see substantial increases in political activity by Hispanics. Counter Socioeconomic theories Jose A. Garcia and Carlos H. Arce’s analysis, however, contradict the Socioeconomic Status theory. In their analysis entitled “Political Orientations and Behaviors of Chicanos: Trying to Make Sense out of Attitudes and Perceptions” they found, those of lower occupational prestige and with lower educational attainment had Moreno 8 higher levels of civic orientation (Garcia and Arce 1988, 137). In fact, Garcia and Arce’s evidence demonstrates positive and strong attitudes toward politics among Hispanics. They define Hispanic “civic orientation” as attitudes focusing on political activities that an active member of the political system pursues, such as voting as an individual expression, getting more Hispanics to vote, and supporting demonstrations to change unfair laws (Garcia and Arce 1988, 137). Garcia and Arce’s found very high levels of civic orientation among Hispanics as well as attitudes reflecting a sense of ethnic identification, or a “collectivist orientation,” were also positive and strong among Hispanics. With this pattern of political orientations, one might expect active levels of political participation. Yet, the political participation rates of Hispanics are rather low compared to other racial groups (Garcia and Arce 1988, 137). Garcia and Arce’s findings are significant for the reason that the findings suggest the absolute opposite of Verba and Nie’s SES theory. Findings from Colorado (LARASA 1989, 104) are not in complete agreement with Garcia and Arce’s findings. The Colorado survey done by the Latin American Research and Service Agency or LARASA, found that among Spanish-surnamed Coloradans, the more educated, higher incomes, and being native born are more likely to be “involved in a Hispanic organization” than were the Mexican-born, (LARASA 1989, 104). Another reason for the contradiction within the SES model is what Leighley and Vedlitz state as: most studies that confirm the SES model have relied primarily on samples of non-Hispanics, and it is assumed that socioeconomic status works similarly Moreno 9 across the ethnic groups. Yet, the empirical evidence on this point is mixed. Leighley and Vedlitz, for example, find that education is significantly related to participation among Mexican-Americans, but not among Asian-Americans, while Harris (1994, 206), Tate (1991, 205 1993, 56), and Dawson, Brown, and Allen (1990, 26) find that education and income are only occasionally related to participation among African Americans. Although the SES model dominates in the study of political participation, there is still much room for debate. One study of political behavior, for example, argues that as levels of education and income in the United States have increased over the past three decades, the level of voter turnout has decreased (Brody 1978, 102). Political Scientists try to tie this theory with the individual’s relationship to the larger society. These discussions have reasoned that as individuals get to the point where they feel comfortable in their everyday life they become less interested in political issues. Putnam (1995, 59), Teixeira (1992, 28), and Uslaner (1995, 36) argue that the decline in political participation over the past 20 years is directly related to the lack of connectedness between individual citizens and the larger political and social community. Clearly, Putnam, Teixeira, and Uslaner believe that behavioral factors are why some minorities participate less in politics. These behavioral factors include organizational structures such as marriage, church-attendance, interest groups, and home ownership. In other words, committed individuals are more likely to participate in politics. As stated earlier, Ulaner, Cain, and Kiewiet convey this concept to be group identification. Katherine Tate’s 1991 study entitled “Black Political Participation in the 1984 and 1988 Presidential Elections,” found that home ownership is not associated with Moreno 10 voting in presidential primary elections. But, evidence concludes that blacks who participate in weekly activities such as church participate more in politics. Group Conflict On that note, Paula McClain and Albert Karning demonstrate the theory that a significant presence of one minority group affects the other minority group. Mclain and Karning conclude that there are few investigations which have examined the relationship between blacks and Hispanics in their struggles for political power and economic advancement. Specifically, they look at Hubert Blalock’s theory of competition which suggests that group competition accounts for some aspects of the discrimination experienced by minorities. Blalock says that competition exists when two or more groups strive for the same finite objectives, so that the success of one may imply a reduced probability that another will attain its goals (Mclain and Karnig 1990, 536). Thus, this leads many to believe self-interest is a factor among minorities. Falcon, for instance, notes that blacks were concerned with desegregation and were not supportive of bilingual education because they feared it would divert resources from black concerns (Falcon 1988, 206). With blacks and Hispanics struggling to achieve political and socioeconomic objectives, there are several possible intergroup patterns. Most importantly, one group may do well at the expense of another (Mclain and Karnig 1990, 542). McClain and Karnig’s findings conclude that as black and Hispanic political successes increase, political competition between Hispanics and blacks are triggered (Mclain and Karnig 1990, 546). Further, a study of ethnic-racial groups in New York City suggests that ethnicracial political culture is independent of, and often more significant than, socioeconomic Moreno 11 status in explaining political participation (Hero 1992, 52). Another study in New York by Dale Nelson found that several Latino groups -- Puerto Ricans, Cubans, and Dominicans -- have “weak participant political cultures,” while blacks exhibit a distinct strong orientation to political participation (Nelson 1979, 236). Self-Identification Rodney E. Hero has conducted a number of studies which examine individual self identification. Self – reference -- the ethnic -- racial names or labels people use to identify themselves are important for various reasons (Hero 1992, 56). First, Self Identification has implications for group cohesion; persons who do not identify themselves as a group are less likely to act as one (Hero 1992, 62). Second, Self-Identification demonstrates group assimilation or acculturation in relation to the larger society. Finally, Self- Identification reveals how one person relates themselves in political society or a political ideology (Hero 1992, 63). Another fascinating theory formed by Frank D. Gillliam, Jr., states symbolic politics and governing coalition theories are used to predict political orientations of blacks, whites, and Hispanics in cities with long-term minority regimes (Gilliam 1996, 56). This theme complements the other theories on political participation. Thus, Frank Gilliam’s analysis leads many to believe that minorities that participate more are influenced by minority empowerment across the political system. Gilliam initially suggests that individuals who become more interested in politics will become part of a group and lead orientations. Moreno 12 Group Consciousness/Political Efficacy Research in political science has also demonstrated the importance of Group Consciousness as a factor influencing individual political behavior (Leighley and Vedlitz 1999, 1094). Miller et al. (1981, 256) find that Group Consciousness is associated with participation for blacks, women, and the poor. Many researchers believe the closer an individual is to a group the more likely the individual will participate in politics. For many minorities it is a sense of belonging to a group that gives much confidence to mobilize. Garcia and Arce argue that individuals with a positive sense of personal and political efficacy are more likely to have preferences, motivations, and apply their resources toward political actions (Garcia and Arce 1988, 46). IV. THEORY AND HYPOTHESIS This paper, therefore, hypothesizes that Hispanics with lower economic status and lower educational attainment are more likely to participate in politics. This hypothesis is related to Garcia and Arce’s theory of Hispanic political participation. Garcia and Arce argue that the Socioeconomic Status theory is truly unique. It contradicts what most scholars have said and widely agree upon. Their theory states: Hispanics with lower economical status and with lower educational attainment have higher levels of civic orientation. Garcia and Arce’s theory reveals a negative relationship between income, education, and levels of participation. This pattern is expected because the prediction is that Hispanics with lower education and economic prestige are more inclined to want to change for the better. Another prediction is Hispanics with lower education and economic prestige form a Moreno 13 desire to mobilize and create coalitions to support more participation among other Hispanics. Garcia and Arce’s evidence demonstrates these higher levels of civic orientations for lower class Hispanics. Again, their findings appear to be inconsistent with the socioeconomic status theory. They oppose this theory because SES tends to categorize all ethnicities in one category and neglects that Hispanics are not the same as other ethnicities. Garcia and Arce’s theory explains the more income and education one holds does not necessarily result in an increase in political participation. Another theory important to this study is the idea of Political Efficacy. As defined earlier Political Efficacy is a psychological factor of confidence that contributes to political participation. Further, an individual attains a feeling of power or capacity to produce a desired effect or effectiveness. The concept of Political Efficacy is tested in the SES theory as a positive relationship between education, income, and levels of participation. Thus, the more educated, and wealthier have higher levels of political efficacy which results in higher levels of political participation. In Leighley and Vedlitz analysis their evidence reveals political efficacy as a negative relationship for Hispanics political participation (Leighley and Vedlitz 1999, 1094). For the purpose of this study a positive relationship between political efficacy, income, education, and levels of political participation is expected. If the results reveal a positive relationship then political efficacy reveals an impact on Hispanics political participation. In addition the concept of Group Consciousness is another important factor in this discussion. As mentioned earlier, Jan Leighley and Arnold Vedlitz analysis entitled “Race, Ethnicity, and Political Participation: Competing Models and Contrasting Explanations” demonstrate the idea of group consciousness. They conclude that the Moreno 14 Group Consciousness model of political participation -- arguably more relevant as an explanation of Hispanic political behavior than of Anglo political behavior. Further there is evidence of intellectual origins of differences in the participation levels of blacks and whites, which posited that blacks participate more than whites, controlling for socioeconomic status, because of their heightened levels of group consciousness (Leighley and Vedlitz 1999, 1098). Consistent with prior theories this study suspects that group consciousness will have a positive relationship with participation for Hispanics. In this study a relationship of lower economic status Hispanics political participation is expected to be affected when controlled for the model Group Consciousness. Granted Garcia and Arce’s findings support their hypothesis and remain remarkable. This analysis plans to further Garcia and Arce’s findings and retest their variables with a limited number of cases from a data set different from their analysis. Moreover, this analysis adds further contribution to a topic that is rarely covered in political science. Indeed there is a limited amount of time to complete this analysis; time will not be an intervening factor in completion of this analysis. V. DATA AND VARIABLES Garcia and Arce explore both arenas of political participation for Hispanics as well as cultural factors such as Spanish language maintenance, foreign born origin, and value systems (Garcia and Arce 1988, 126). This paper explores the electoral participation of Hispanics and employs The American National Election Survey 2000: Pre-and Post-Election Survey (NES) for the levels of participation of Hispanics. The sample design includes a sample selection of 132 individuals who chose Spanish descent Moreno 15 as their ethnicity. Garcia and Arce, however, employ The Latino National Political Survey to reveal the political participation of Hispanics. The independent variables that are used in this study are income, level of education, group consciousness, and political efficacy. The limited evidence on Hispanic political participation suggests lower than average participation rates, as well as involvement in a limited range of activities. Socioeconomic Status is viewed as the major determinant of an individual’s political participation (Brady et al 1995, 87). Citizen activism is an expected norm for a democratic society, yet the actual level of individual involvement is minimal. At the same time, there are costs and resources involved for political participation. In terms of resources, the demands can be requests to work on campaigns, contribute to organizations, and/or campaigns, signing petitions, or writing letters on behalf of concerns or issues (Garcia and Arce 1988, 45). The individual costs are time, financial resources, communication and organization skills, and personal orientations that include self-confidence, efficacy and trust (Garcia and Arce 1988, 45). The traditional base for individual resources falls within the rubric of socioeconomic resources--education, income, and occupation. For the purpose of this study occupation is not used as one of the independent variables, instead education and income represent the socioeconomic status variables. Education fosters democratic values such as individual rights and responsibilities, involvement, political expressions, and freedoms. It also nurtures a sense of citizen competence, as well as providing skills for political learning (Garcia and Arce 1988, 46). The independent variable level of Moreno 16 education meets the criteria of face validity, in which the common understanding is that in most cases more educated individuals can understand complex and abstract ideas. The other part of the Socioeconomic Status theory is income. Income levels affect participation in terms of economic resources, time, and opportunities. Individuals who have a direct stake in political outcomes, as well as policy preferences, will be involved politically (Leighley 1990; Huckfeldt and Sprague 1987). Thus, the independent variable income meets the criteria of face validity, where common knowledge assumes that a person in higher occupational status positions and higher income levels are directly motivated and invested in political involvement (Verba and Nie 1972; Miller et al. 1981). The discussion of individual political participation entails resources, motivations, and opportunities. The motivation dimension deals with attitudinal factors as efficacy and group consciousness (Verba and Nie 1972; Miller et al. 1981). The control variable group consciousness and the independent variable political efficacy are measurements which meet the criteria of face validity. These two variables are consistent with an agreed definition of a generalized concept. In other words, individuals with a positive sense of confidence in the political system are more likely to mobilize and move toward political actions. The sample consists of one hundred and thirty-two Hispanics. These one hundred and thirty-two individuals are asked to respond to various questions regarding their political participation. For instance, one of the questions is, “Did you vote in the 2000 election?” An additive index is engaged to formulate the dependent variable by summing up the different categories of political participation such as campaigning, contributions to Moreno 17 political parties, involvement in political organizations, and voting. Next the independent variable income is recoded into three categories. In addition, the independent variable level of education is recoded into three categories as well (see table 1, pg. 21). VI. METHODS The hypothesis being tested in this study is that Hispanics with lower economic status and with lower educational attainment have higher levels of civic orientation. Both dependent and independent variables are ordinal-ordinal, in which various statistical tests are engaged. The statistical tests that are engaged in the study are bivariate tests, ChiSquare, Somer’s D, Gamma, and a multiple regression. A multiple regression test is primarily intended for interval variables; however, a multiple regression test is widely used in political science to test ordinal relationships. The other statistical tests that are engaged in the study are the most appropriate for ordinal relationships. A bivariate analysis employs whether there is a relationship between the independent variable level of education and the dependent variable level of participation. Then, a Chi-Square statistical test shows whether level of education and level of participation are independent of each other. Also, the chi square compares the observed distribution of cases among the cells with the distribution that would occur if there were no relationship. Next, a Somers’D test is used to determine the strength of the relationship between level of education and level of participation. Finally, the statistical test Gamma is used to determine the positive or negative relationship between level of education and level of participation. Moreno 18 The second bivariate analysis employs whether there is a relationship between the independent variable household income and the dependent variable level of participation. Next, a chi square statistical test is also used to determine whether the variables, household income and level of participation are independent of each other. Then, a Somer’s D test is used to determine the strength of the relationship between household income and level of participation. Finally, a Gamma statistical test is used to indicate whether there is a positive or negative relationship between household income and level of participation. A third bivariate analysis is employed to determine whether there is a relationship between the independent variable group consciousness, and the dependent variable level of participation. Second, a Chi-Square statistical test is used to examine the significance of group consciousness and level of participation, and whether both variables are independent of each other. Third, a Somer’s D statistical test is used to test for the strength of the results. Finally, a Gamma statistical test is used to indicate whether there is a positive or negative relationship (direction) between the two variables. The final bivariate analysis is engaged to determine whether there is a relationship between the independent variable political efficacy and the dependent variable level of participation. Next, a Chi Square statistical test is used to determine the significance of the relationship between political efficacy and level of participation. Then a Somer’s D statistical test is used to reveal the strength of the relationship between the both variables. Finally, a Gamma statistical test is used to determine the positive or negative relationship (direction) between both variables. Moreno 19 Unlike the bivariate analysis a multivariate analysis is used between the variables level of education and level of participation, when controlling for Hispanic influence or group consciousness. The exact statistical tests of Chi-Square, Somer’s D, and Gamma used for the bivariate analyses are employed in this multivariate analysis to determine whether the results will remain stagnant when controlling with another variable. The second multivariate analyses demonstrated are between the variables of household income and level of participation, when controlling for Hispanic influence or group consciousness. As stated in the first multivariate analysis, the statistical tests ChiSquare, Somer’s D, and Gamma are used to determine if the relationship remains stagnant when controlling with another variable. The final analysis revealed is a multiple regression which determines the relationship between the four independent variables and the dependent variable. The statistical tests administered in the multiple regression are the regression coefficient, standardized coefficient, and the R-square value. First, the regression coefficient predicts how much change in the dependent variable is associated with a unit increase in the independent variables. Second, the standardized coefficient predicts how much change in the dependent variable is associated with a unit increase in the independent variables. Finally, the R-square value indicates the proportion of variation in the dependent variable explained by the independent variables. VII. RESULTS The Frequency tests below explain the basic patterns in the variables before the variables are tested with one another. As seen in table one, the dependent variable Moreno 20 participation demonstrates three main categories for the different levels of participation. 41.2 percent of Hispanics report doing nothing in participation with politics. In other words, 41.2 percent of Hispanics claim that they did not influence the vote of others. Also, they did not display buttons, stickers, signs, meetings, attend rallies, nor did they vote. Thus, out of one hundred and thirty-two Hispanics, 41.2 percent did not participate in any electoral political participation. Yet, 33.3 percent of Hispanics participated in one activity while 20.5 percent participated in two or more activities. Next, as seen in Table 1, a majority of Hispanics in NES exhibit more than 12 years of the highest level of education completed. The level of education data demonstrates that 43.9 percent completed up to twelve years of school while 45.5 percent had thirteen to sixteen years of education. Only 10.6 percent of Hispanics had more than17 years of the highest level of education completed. This is a 33.3 percent gap between those individuals with more than 12 years of the highest level of education, and those with more than 17 years of the highest level of education. The next frequency as seen in Table 1 examines the question: “How much Hispanic influence exists in American politics from the point of view of Hispanics. Clearly, the data below illustrates 66.7 percent feels there is too little Hispanic influence in American politics. Whereas only 4.2 percent of Hispanics feel there is too much Hispanic influence in American politics. The data regarding, “Does the Hispanic R believe their vote matters?” 52.2 percent disagree strongly with this question. Only 8.7 percent of Hispanics believe strongly that their vote matters. Evidently, there is a clear consistency of negativity with the overall opinion of Hispanic politics in American politics. Moreno 21 The frequency of household income as seen in Table 1 confirms 61.9 percent claim their household income to be $25,000-$104,999. 31.9 percent of Hispanics claim their household income to be none or less than $25,000 while only 6.2 percent confirm their household income to be $105,000-$200,000 and over. Dept: Participation Table 1*** Frequencies for Hispanic Respondents Frequency Valid Percent Nothing One Activity Two or more Activities Total 61 44 27 132 46.2 33.3 20.5 100.0 58 60 14 132 43.9 45.5 10.6 100.0 Level of Education Up to 12 Years 13 to 16 Years 17 Years and Up Total Hispanics Influence 1. Too Much Influence 2. Just about the Right Amount 3. Too Little Influence Total Missing System 4 28 64 96 36 4.2 29.2 66.7 100.0 27.3 Does R Believe their vote matters 1. Agree Strongly 2. Agree Somewhat 3. Neither Agree Nor Disagree 4. Disagree Somewhat 5. Disagree Strongly Total Missing System 8 9 8 8.7 9.8 8.7 19 48 92 40 20.7 52.2 100.0 Moreno 22 Household Income None or Less Than $25,000 $25,000-$104,999 $105,000-$200,000 And Over Total Missing System 36 70 7 113 19 ***Source: National Election Survey-NES A bivariate test for level of education and participation is shown below in Table 2. The results in Table 2 exhibit that the more educated Hispanic tends to participate in more activities. 50 percent of Hispanics who participated in two or more activities revealed their level of education was 17 years or more while 10.3 percent of Hispanics with an education level of up to twelve years did nothing to participate. Indeed, the results in Table 2 confirm the Socioeconomic Status theory holds true, where the more educated are more likely to participate more in politics. These results in Table 2 confirm the opposite of the hypothesis in this study. Further, these results in Table 2 reveal that education and income are significant in political participation of Hispanics. Participation Table 2 Level of Education Up to 12 years 13 to 16 years 17yearsand up Total Nothing 56.9% 40.0% 28.6% 46.2% One Activity 32.8% 36.7% 21.4% 33.3% Two or more Activities 10.3% 23.3% 50.0% 20.5% Moreno 23 100.0% 58 Total 100.0% 60 100.0% 14 100.0% 132 cases The results in Table 3 examine the strength, direction, and significance of the bivariate test regarding participation and level of education. There is a very strong statistical significant difference of .012 which lets us reject the null hypothesis. Also, the Somers’D result exhibits a moderate value of .231, which concludes a moderate relationship between levels of education and levels of participation. Gamma reveals a .381 moderate positive relationship between levels of educations and levels of participation. These tests do not have any missing values and account for all 132 cases. Somers’D Table 3 Level of Education Chi-Square. Gamma .231 .012 .381 The next bivariate test examines the relationship between participation and household income. Here the results in Table 4 are similar to the level of education. Both data results in Table 2 and 4 confirm the Socioeconomic Status theory to be valid. As seen in Table 4, 63.9 percent of Hispanics who revealed an annual household income of none or less than $25, 000 did nothing to participate in politics. Table 4 below also demonstrates that 14.3 percent of Hispanics, who reported an annual household income of $105,000 to $200,000 and over, participated in two or more activities. The result in Table 4 show that the more income one makes the more likely one participates in politics. Moreno 24 Participation Nothing Table 4 Household Income None or Less $25,000$105,000than $25,000 $104,999 $200,000 and Over 63.9% 40.0% 14.3% Total 46.0% One Activity 27.8% 32.9% 42.9% 31.9% Two or More Activities 8.3% 36 27.1% 70 42.9% 7 22.1% 113 cases Evidently the Chi-Square shown in Table 5 reveals there is a very strong significance level of .036. Therefore, we can feel confident in rejecting the null hypothesis. Also, the Somer’s D value of .247 demonstrates a moderate relationship between the levels of participation and Household income. The Gamma value of .476 demonstrates a moderate positive relationship as well. Somers’D Table 5 Household Income Chi-Square Gamma .247 .036 .476 The third bivariate test as seen in Table 6 is the relationship between Hispanic influence and levels of participation. The interesting facts of Table 6 are that 20.3 percent of Hispanics who feel Hispanics have too little influence did nothing to participate. On the other hand, 50 percent of Hispanics who feel Hispanics have too much influence did nothing to participate. Furthermore, 29.7 percent of Hispanics who felt Hispanics have too little influence participated in two or more activities while .0 percent of Hispanics who felt Hispanics have too much influence participated in two or more activities. The results in Table 6 do not support the hypothesis. These results Moreno 25 reveal that there is no evidence of Hispanics forming coalitions to mobilize and engage in political participation. Nothing Too Much Influence 50.0% Table 6 Hispanic Influence Just About the Right Amount 46.4% Too Little Influence 20.3% 29.2% One Activity 50.0% 32.1% 50.0% 44.8% Two or More Activities .0% 4 21.4% 28 29.7% 64 26.0% 96 Participation Total As seen in Table 7, the Somers’D value reveals a .267 value which exhibits a moderate relationship. The Gamma value of .356 in Table 7 also demonstrates a moderate relationship between level of participation and Hispanic influence. The ChiSquare significance level of .085 in Table 7 is statistically significant. Thus, we cannot reject the null hypothesis. Somers’D Table 7 Hispanic Influence Chi-Square Gamma .267 .085 .396 The fourth bivariate test determines the relationship between Political Efficacy and the levels of participation. The total percentages as seen in Table 8 represent only three categories below and not the five categories used to test the original bivariate. These three categories in Table 8 are chosen because these categories are the most relevant results. The results in Table 8 demonstrate that 16.7 percent of Hispanics who Moreno 26 feel their vote does not matter did nothing to participate while 62.5 percent of Hispanics who feel their vote does matter did nothing to participate. The results in Table 8 also show about 80 percent who feel their vote does not matter participated in one or more activities while about 37.5 percent of Hispanics participated in one or more activities. The results in Table 8 demonstrate support for mobilization. In other words, the results in Table 8 reveal there is a strong case that the 80 percent who feel their vote does not matter decided to take action and participate. The results in Table 8 demonstrate a positive direction. Since the Political Efficacy variable is scaled 1 to 5, there is a positive direction with 1 representing agree strongly and 5 disagree strongly. As stated earlier, the Socioeconomic Status theory expects a negative relationship for Political Efficacy. Table 8 Does Respondent believe their Vote matters (Political Efficacy) Participation Agree Strongly Neither Agree Disagree Total Nor Disagree Strongly 62.5% 50.0% 16.7% 31.5% Nothing One Activity 37.5% 37.5% 43.8% 41.3% Two or More Activities .0% 8 12.5% 19 39.6% 48 27.2% 92 cases Table 9 shows that the Somers’D .391 and Gamma .573 demonstrates a moderate relationship between Political Efficacy and levels of participation. The Chi-Square value of .005 exhibits probability that the relationship does not exist. There is a high statistical significance, which leads us to reject the null hypothesis. Moreno 27 Table 9 Does Respondent believe their Vote matters (Political Efficacy) Somers’D Chi-Square Gamma .391 .005 .573 Next, a multivariate analysis of levels of education and levels of participation when controlling for Hispanic influence revealed that there was a significant number of cases that fell under the category of too little influence. In this analysis, the decision to control for Hispanic influence is important for support of the hypothesis. Similar to Garcia and Arce’s results with the Group Consciousness model this study tests if group consciousness will overcome Socioeconomic Status when controlled. The category “too little influence” is chosen, because if group consciousness can overcome Socioeconomic Status theory, then it would be in this category where Socioeconomic Status theory would break down. However, the results reveal that Socioeconomic Status theory still holds true even when controlling for the category. There is still a moderate relationship overall, for the values of Somers’D .291 and Gamma .491 are positive. The relationship is still statistically significant positive. We can confidently agree that the Socioeconomic Status theory still holds true between levels of education and levels of participation, even when controlling for Hispanic influence. The second multivariate analysis explains household income and the levels of participation when controlling for Hispanic influence. Due to the majority of individuals in the category, “too little influence,” group consciousness is primarily tested in this category where we might see a break down of the Socioeconomic Status theory. Here the values of Somers’D .002 and Gamma .576 confirm a moderate relationship between household income and levels of participation when controlling for Hispanic influence. Moreno 28 Further, the Chi-Square value of .086 is statistically significant, which lets us reject the null hypothesis. The final analysis as seen in Table 10 is a multivariate regression which shows the relationship of the four independent variables to the levels of participation. The R-Square value reveals that there is a 36.2 percent of variance explained by the regression. In other words, the R-Square value indicates the proportion of variation in the dependent variable explained by the independent variables. The adjusted R-Square is the same but compensates for this small sample consisting of one hundred and thirty-two Hispanics. Next, the slope below, or B predicts how much change in levels of participation is associated with a unit increase in each of the independent variable below, holding the other independent variables constant. In addition, Table 10 shows the Beta values as a relative strength for the values of both whether the respondent believes their vote matters and household income. The multivariate regression is used to compare the Beta values, so the regression allows us to see which independent variable has the biggest impact on the levels of participation. Clearly, as shown below, the biggest impact on the levels of participation is the independent variable whether or not the respondent believes their vote matters. The positive direction of the independent variable, “Does respondent believe their vote matters,” explains that the more an individual disagreed that their vote matters the more they participated in political activities. Taking a closer look at the bivariate analysis (see Table 8), the original scale goes from negative to positive. Thus, a positive relationship exists. Moreno 29 Finally, the significance levels shown in Table 10 indicate that it is difficult to reject the null hypothesis for the independent variable Hispanic influence because of the statistical significance. However, the other values are weak to moderate significances, which lead us to reject the null hypotheses for these three independent variables. Table 10 Regression Constant Level of Education B .173 Beta .154 Significance .153 Hispanics Influence .232 .177 .077 Does R believe their vote matters .189 .332 .002 HH income-all HH’s .053 .244 .024 R SQUARE=.362 ADJUSTED R SQUARE=.324 VIII. DISSCUSSION In analyzing these final results, we must discuss the criteria of causality of each independent variable. First, the relationship between level of participation and level of education demonstrates a causal relationship. For instance, both variables change together logically and plausibly. Since we rejected the null hypothesis because there is an association between the two variables, the Socioeconomic Status theory supports this logical connection by claiming that the more educated an individual is the more likely that individual will participate in politics. Granted, this causal relationship does not support the hypothesis being studied, but it does establish a stronger relationship for the Socioeconomic Status theory. Finally, level of education and level of participation may Moreno 30 be explained away through the influence of other independent variables because of the multiple regression results. Second, the relationship between level of participation and household income also demonstrate a causal relationship. Indeed, both variables change together logically and plausibly. Again, since we rejected the null hypothesis, there is an association between these two variables. The Socioeconomic Status theory that supports level of education holds the same results for income. Thus, the more income an individual accumulates the more likely an individual will participate in politics. Again this causal relationship does not support the hypothesis being studied, but establishes an even stronger relationship for the Socioeconomic Status theory. Finally, the observed relationship between level of participation and income is not explained away through the influence of other independent variables. Third, the variable Hispanic influence results demonstrate a causal relationship with level of participation. Our results confirm the rejection of the null hypothesis for these two variables. Clearly, both of these variables are associated and follow a logical, plausible order. The Group Consciousness theory explained earlier demonstrates a strong argument for this causal relationship and the results shown above. Also, the observed relationship between level of participation and Hispanic influence is not explained away through the influence of other independent variables. Finally, the Political Efficacy variable which asks the respondent if they believe their vote matters in the 2000 election demonstrates a causal relationship with level of participation. For example, both variables change together logically and plausibly. We can reject the null hypothesis since there is an association between these two variables. Moreno 31 Indeed, the Political Efficacy theory supports the results of the causal relationship. As mentioned earlier, the Political Efficacy is a psychological factor of confidence that contributes to political participation. Further, an individual attains a feeling of power or capacity to produce a desired effect or effectiveness. The concept of Political Efficacy is tested in the Socioeconomic Status theory as a positive relationship between education, income, and levels of participation. Thus, the more educated and wealthier have higher levels of Political Efficacy which results in higher levels of political participation. The results of Political Efficacy help support the hypothesis and support the theory behind the results by confirming a mobilization factor. Also, the observed relationship between level of participation and efficacy is not explained away through the influence of other independent variables. The conclusion of the results confirm that the Socioeconomic Status theory holds true: the more educated, wealthier individuals participate more in politics. These results demonstrate that more educated, wealthier Hispanics in this study participated more in American politics. However, there are some interesting results with group consciousness and efficacy, which supports the hypotheses. The results demonstrate mobilization from Hispanics. Also, the results examine whether the theories in this study are valid within significant subgroups of the population. This is very important in minority participation, especially participation involving Hispanics, because of the large population of Hispanics in the United States. The problem that results in the “general” theories of participation is that testing data from national election surveys almost always consist of primarily Anglos. Obviously, this presents a problem with the results. It is almost impossible to apply Moreno 32 certain theories to Hispanics if the survey consists mostly of Anglos. The argument stands that there are limitations with many of the theories mentioned earlier. How can this data contribute to another subgroup if prior research has shown a vast majority of Anglos are used in national surveys? There are limitations within this study because the lack of Hispanic respondents in national surveys makes it difficult to understand the entire community of Hispanics. Clearly, the data reveals the small N cases of Hispanic respondents, but there are still 132 respondents, so the study was still able to complete statistical analyses. VIII. CONCLUSION This study examined electoral participation involving Hispanics from an approach that opposed Verba and Nie’s prior conclusions. The evidence from this study, however, reveals that Verba and Nies conclusions regarding socioeconomic status and participation remain valid. Since this study tested electoral participation with Hispanics, activity participation is another method one could test to see if there are different or similar results. Future researchers could attempt to use these results and prior research to conduct their own analyses. There is still much to be learned about Hispanic politics in America. Because so little research has been done in this area, there is always an opportunity for more insightful research. Garcia and Arce’s theory of Hispanic political participation planted the seed for this analysis. They specifically focused on the Hispanic community and their patterns of civic orientations. They define Hispanic “civic orientation” as attitudes focusing on political activities that an active member of the political system pursues, such as voting as an individual expression, getting more Hispanics to vote, and supporting demonstrations Moreno 33 to change unfair laws (Garcia and Arce 1988, 137). Oppose to Garcia and Arce’s study, this study used a different measurement for participation that focused primarily on electoral politics, with the exception of political efficacy and group consciousness. Garcia and Arce focused primarily on the attitudes of Hispanics, and they used a secondary data set, specifically intended for Hispanics; while in this study, the secondary data NES is utilized. While the Hispanic population in America continues to grow, the need to understand why there is such little Hispanic representation in politics remains. There needs to be a marginal change in Hispanic participation in survey samples in order for a researcher to have a larger sample size. In this study, the small sample size of Hispanics proved that it would have been very helpful if more Hispanics were involved in the process. However, because of the limited number of Hispanics, the results make it more difficult to come to a conclusion. Hopefully, there will be an increase in the National Election Survey for 2004, so future researchers will have a larger sample to test for more accurate, real -- world results. Moreno 34 Bibliography Bennett, Linda, and Stephen Bennett. 1989. “Enduring Gender Differences in Political Interest: The Impact of Socialization and Political Dispositions.” American Political Quarterly 17: 102-22. Blalock, Hubert M. 1967.Toward a Theory of Minority-Group Relations. New York: John Wiley & Sons. Brody, Richard A. 1978. “The Puzzle of Political Participation in America.” In The New American Political System, ed. Anthony King. Washington, DC: American Enterprise Institute. Falcon, Angelo. 1988. “Blacks and Latino Politics in New York City.” In Latinos in the Political System, ed. F. Chris Garcia. Notre Dame, IN: Notre Dame University Press. Garcia, Jose A., and Carlos H. Arce. 1988. “Political Orientations and Behaviors of Chicanos: Trying to Make Sense Out of Attitudes and Perceptions.” In Latinos and the Political System, edited by F. Chris Garcia, 125-151. Notre Dame, Ind: University of Notre Dame Press. Gilliam, Frank H., Jr. “Exploring Minority Empowerment: Symbolic Politics, Governing Coalitions and Traces of Political Style in Los Angeles.” American Journal of Political Science, Vol. 40, No. 1 (Feb., 1996), 56-81. Gray, Virginia, and Russell L. Hanson. 2004. Politics in the American States. Washington, DC. CQ PRESS. Pgs. 13-50. Hero, Rodney E. 1992. Latinos and the U.S., Political System. Philadelphia, Temple Moreno 35 University Press. Pgs. 56-85. LARASA (Latin American Research and Service Agency). 1989. Hispanic Agenda Poll. Denver, Colorado. Leighley, Janet. 1990. “Social Interaction and Contextual Influences on Political Participation.” American Politics Quarterly 18 (October): 458-75. Leighley, Jan E. and Arnold Vedlitz. “Race, Ethnicity, and Political Participation: Competing Models and Contrasting Explanations.” The Journal of Politics, Vol. 61, No.4 (Nov., 1999), 1092-1114. McClain, Paula D, and Albert Karnig. “Black and Hispanic Socioeconomic and a Political Competition.” The American Political Science Review, Vol. 84, No 2 (Jun 1990), 535-545. Milbrath, Lester, and M. L. Goel. 1977. Political Participation. 2nd ed. Chicago: Rand McNally.208-239 Nelson, Dale. 1979. “Ethnicity and Socioeconomic Status as Sources of Participation: Putnam, Robert D. 1995. “Turning In, Tuning Out: The Strange Disappearance of Social Capital in America.” PS 28: 664-83. Tate, Katherine. 1991. “Black Political Participation in the 1984 and the 1988 Presidential Elections.” American Political Science Review 85(4): 1159-76. Teixiera, Ruy A. 1992. The Disappearing American Voter. Washington DC: Brookings Institution. “The Case for Ethnic Political Culture.” American Political Science Review 73, no. 4 (December): 1024-1038. Uhlaner, Carole J; Cain, Bruce E. and Kiewiet Roderick. “Political Participation of Moreno 36 Ethnic Minorities in the 1980s.” Political Behavior. Vol. 11, No 3 (Sep., 1989), 195- 231. Uslaner, Eric M. 1995. “Faith, Hope, and Charity: Social Capital, Trust, and Collective Action.” Presented at the annual meeting of the American Political Science Association. Verba, Sidney, and Norman H. Nie. 1972. Participation in America: Political Democracy And Social Equality. New York: Harper and Row.