Trichinella spiralis: Biology, Life Cycle & Treatment

advertisement

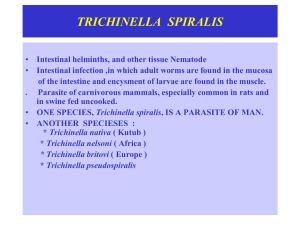

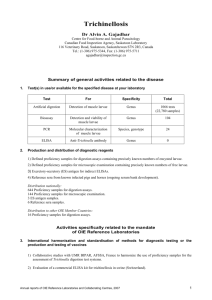

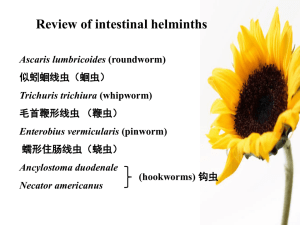

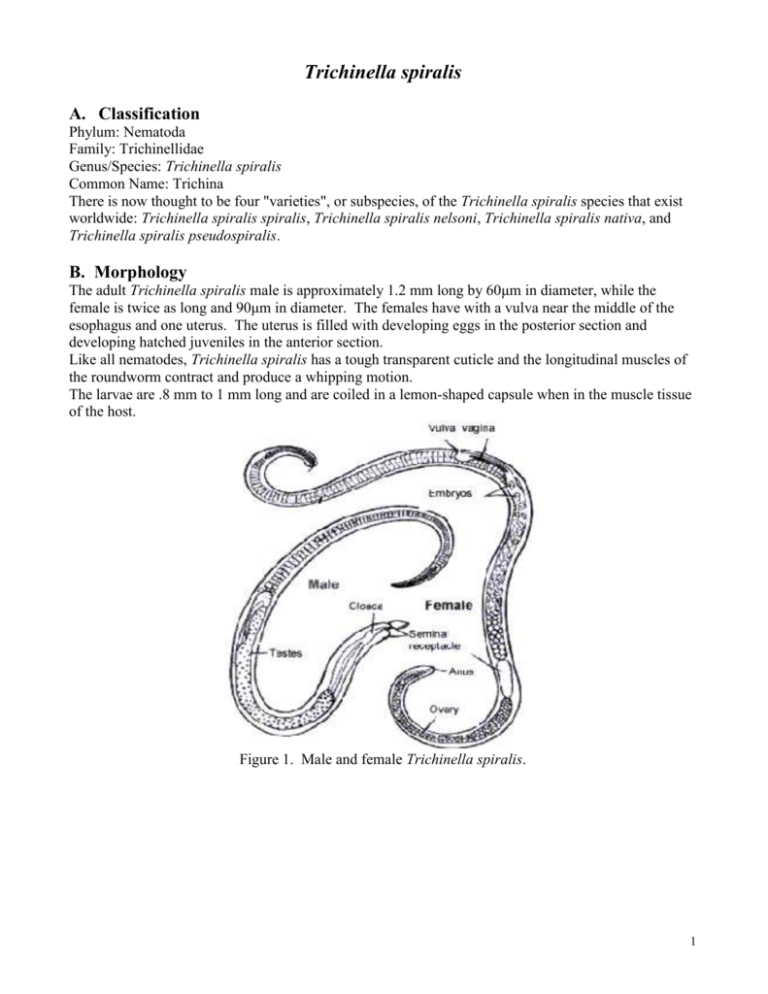

Trichinella spiralis A. Classification Phylum: Nematoda Family: Trichinellidae Genus/Species: Trichinella spiralis Common Name: Trichina There is now thought to be four "varieties", or subspecies, of the Trichinella spiralis species that exist worldwide: Trichinella spiralis spiralis, Trichinella spiralis nelsoni, Trichinella spiralis nativa, and Trichinella spiralis pseudospiralis. B. Morphology The adult Trichinella spiralis male is approximately 1.2 mm long by 60μm in diameter, while the female is twice as long and 90μm in diameter. The females have with a vulva near the middle of the esophagus and one uterus. The uterus is filled with developing eggs in the posterior section and developing hatched juveniles in the anterior section. Like all nematodes, Trichinella spiralis has a tough transparent cuticle and the longitudinal muscles of the roundworm contract and produce a whipping motion. The larvae are .8 mm to 1 mm long and are coiled in a lemon-shaped capsule when in the muscle tissue of the host. Figure 1. Male and female Trichinella spiralis. 1 Figure 2. Coiled Trichinella spiralis larva freed from the cyst. C. Lifecycle and Epidemiology Trichinella spiralis has no stages outside of the definitive host which can be hogs, humans, bears, dogs, cats, rats, and a variety of other mammals. The life cycle begins when a potential definitive host feeds on another definitive host that contains the infective larvae. The mammal ingests the J1 larvae, which are encysted in the muscles of the host. After exposure to gastric acid and pepsin, the larvae are released from the cysts and enter the small intestine mucosa where they develop into adult worms. During this phase, the adult worms mate and then the male worms die. The adult females penetrate the mucosa of the intestine and produces larvae. The females will produce approximately 1,500 larvae over the next four to sixteen weeks and then die. The larvae enter a muscle fiber and form a fibroblast cyst. In time the cyst becomes surrounded by a calcarious layer.. The larvae are most frequently found in very active muscles, for example the diaphragm, abdominal walls, tongue, biceps, eyes, larynx, and deltoid muscle fibers. The larvae in the cyst develop into the infective first stage-larva in about 3 weeks. Thus, the definitive host serves as the intermediate host. If a human ingests raw or undercooked pork, rat, bear, etc., the they can become infected with Trichinella spiralis. Within cysts, larvae remain viable for many years; up to 25 years in man and 11 years in pigs. Figure 3. Lifecycle of Trichinella spiralis. 2 Figure 4. Internal portion of the lifecycle D. Geographic Distribution Trichinella spiralis is found all over the world. However, it is more prevalent in Europe, the United States, and Asia. Trichinella spiralis spiralis is found in temperate regions. Trichinella spiralis nelsoni is commonly found in the tropical regions. Trichinella spiralis nativa is found in the Artic, while Trichinella spiralis pseudospiralis is found in New Zealand. Figure 5. Geographic Distribution 3 E. Pathology and Symptoms Trichinosis, also called trichinellosis, is the infection caused by Trichinella spiralis. Symptoms can range from none at all to very serious symptoms depending on the number of infectious worms present. The first symptoms of trichinosis may occur 1-2 days after infection. It is often misdiagnosed because of the vagueness of symptoms. These first symptoms include nausea, diarrhea, vomiting, fatigue, fever, and abdominal discomfort. When the newborn larvae are released into tissues and start to migrate, usually five to six weeks after infection, the symptoms may include pneumonia, pleurisy, encephalitis, meningitis, nephritis, deafness, and peritonitis. As the larvae start to penetrate muscle cells, muscular pain, breathing difficulties, swelling of masseter muscles, a weak pulse, and a low blood pressure may occur. The average case of trichinosis is not severe and produces no noticeable discomfort. Death may occur in severe cases. Complications of trichinosis are secondary symptoms of the infection. Some of these complications may include skeletal muscle cysts, heart complications, inflammation of the heart walls, lung complications, pneumonitis, pleurisy, central nervous system complications, meningitis, encephalitis (inflammation of the brain), vision disorders, and hearing disorders. F. Diagnosis Within the first couple of weeks of infection, Trichinella spiralis may be identified using fecal samples. Trichinosis may be diagnosed using blood tests, serum eosinophils, muscle biopsy, or microscopic examination of muscle tissue. If trichinosis is present the blood test will show an increase in the number of eosinophils. Microscopic examination of muscle tissue will show larvae. Trichinosis may be misdiagnosed as food poisoning or muscular rheumatism. Muscular rheumatism is characterized by stiffness, pain, or swelling in the muscles. Figure 6. Photomicrograph of Trichinella spiralis in a human muscle tissue. G. Treatment There is no treatment for the trichinosis infection, but treatment may be given to help relieve the symptoms. Thiabendazole may be used only in the early stages of trichinosis, during the incubation state. Corticosteroids may be used with thiabendazole if it is in the larval migration stage, but steroids may prolong the intestinal phase of the infection. Pain medications, bed rest, fluids, and hospitalization 4 are also recommended for treatment. Standard antiparasite drugs may be used to dislodge some of the worms. H. Public Health and Eradication Legislation in the United States has required that pigs should be fed with meat which is thoroughly cooked. To prevent infection it is recommended to heat pork to at least 170ºF and to cook wild game meat thoroughly. Meat grinders should be cleaned thoroughly to prevent contamination. Curing, drying, smoking, or microwaving does not effectively kill infective worms. Slaughter testing is one preventative measure that may be used. Small pieces of pork are collected from the diaphragm and are then examined microscopically for the presence of worms. Countries have imposed trade restrictions that do not use this test. Freezing the meat at –10ºF will kill the Trichinella spiralis instantaneously. Pork that is intended for use in processed products is required by the U.S. Department of Agriculture to be frozen for at least a half hour at –30ºF. Irradiation is also another preventative measure. 5 Works Cited “A-Z Guide to Parasitology.” Accessed 16 March 2005. 2005. <http://www.soton.ac.uk/~ceb/Diagnosis/Vol7.htm>. “Complications of Trichinosis.” Wrong Diagnosis. Accessed 16 March 2005. 2005. <http://www.wrongdiagnosis.com/t/trichinosis/complic.htm>. “Diagnostic Tests for Trichinosis.” Wrong Diagnosis. Accessed 16 March 2005. 2005. <http://www.wrongdiagnosis.com/t/trichinosis/tests.htm>. Gamble, Ray. “Trichinae.” Pork Facts- Food Quality and Safety. Accessed 16 March 2005. 2005. <http://www.aphis.usda.gov/vs/trichinae/docs/fact_sheet.htm>. “Misdiagnosis of Trichinosis.” Wrong Diagnosis. Accessed 16 March 2005. 2005. <http://www.wrongdiagnosis.com/t/trichinosis/misdiag.htm>. “Treatments for Trichinosis.” Wrong Diagnosis. Accessed 16 March 2005. 2005. <http://www.wrongdiagnosis.com/t/trichinosis/treatments.htm>. “Trichinella spiralis in human muscle.” Drkoop.com. Accessed 16 March 2005. 2005. <http://www.drkoop.com/ency/93/ImagePages/2638.html>. “Trichinella spiralis.” Biology of Parasitism. Accessed 16 March 2005. <http://ucdnema.ucdavis.edu/imagemap/nemmap/ENT156HTML/E156trichinellaB>. The Trichinella Page. Columbia University in the City of New York 2004. Accessed March 16, 2005. < http://www.trichinella.org>. Trichinella spiralis Homepage. University of Pennsylvania 2004. Accessed March 16, 2005. <http://cal.vet.upenn.edu/dxendopar/parasitepages/trichocephalids/t_spiralis.html#lifecycle>. Trichinella spiralis. Accessed March 16, 2005. <http://ucdnema.ucdavis.edu/imagemap/nemmap/Ent156html/nemas/trichinellaspiralis>. Trichinellosis. Center for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Infectious Diseases, Division of Parasitic Diseases, Image Library. Accessed March 16, 2005. <http://www.dpd.cdc.gov/dpdx/HTML/Trichinosis.htm>. Angela Chung Drew Dickinson Carrie Barker March 18, 2005 6