The Harlem Renaissance

advertisement

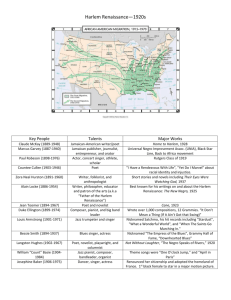

The Harlem Renaissance Zora Neale Hurston “from Dust Tracks on a Road” p. 830 Langston Hughes “Dream Variations” p. 842 “The Negro Speaks of Rivers” p. 841 Claude McKay “The Tropics in New York” p. 843 Countee Cullen “From the Dark Tower” p. 848 “Incident” handout and others… Harlem Renaissance, 1925-1935 Harlem In 1925 a New York Herald Tribune article announced, "we are on the edge, if not in the midst, of what might not improperly be called a Negro Renaissance." The causes of this renaissance--as with all such movements--were financial and educational. Blacks participated in the postwar prosperity--although to a much lesser extent than did whites--and the young generation of literate and literary blacks made the best of it. Many of the most gifted gravitated to a center of black population north of 125th Street in Upper Manhattan that gave its name to the Harlem Renaissance. Harlem nightlife attracted white audiences, and black culture began to receive serious critical attention from white intellectuals. Locke and Van Vechten The movement was shaped significantly by the influence of Alain Locke, a Howard University philosopher, the first black Rhodes Scholar, and editor of The New Negro, in whose pages were published many of the best and most influential essays of the decade, and by Carl Van Vechten, a white editor and patron who became both literary patron and close friend to many of the best black writers of the period, including Langston Hughes, James Weldon Johnson, and Zora Neale Hurston. Desegregating the Arts The Harlem Renaissance is generally considered to have begun in 1917, when two events marked a turning point for black literary and artistic achievement: Seven Arts became the first desegregated white magazine in the twentieth century by publishing three poems by Claude McKay, and for the first time there were plays with black casts on Broadway, with three by white dramatist Ridgely Torrence. Writers The brilliant achievements of black composers and musicians often deflected attention from the literary aspects of the movement. Nevertheless, literature became the focal point of the movement, and though, among the writers, only Langston Hughes became a familiar name, the fleet of young novelists and poets launched by the renaissance wrote a body of enduring works of American literature. The roll is stunning: biracial novelist and poet Jean Toomer; poet Hughes poet Countee Cullen; novelist and poet McKay; writer and editor Jessie Fauset; novelist and folk anthropologist Hurston; novelist Nella Larson; poet and novelist Arna Bontemps; novelist and editor Wallace Thurman. Hughes Accomplished as a writer of fiction and drama, but known most extensively for his poetry, Hughes published his first great poem, and still perhaps his most anthologized, "The Negro Speaks of Rivers," in 1921 at age nineteen. His two poetry collections published in the 1920s were The Weary Blues (1926) and Fine Clothes to the Jew (1927). Cullen Cullen, sometimes called the poet laureate of the Harlem Renaissance, was the most popular black poet of his time. His poetry frequently addressed issues relating to social marginality, such as race, religious hypocrisy, and homosexuality. He published his first, and many think his best, collection, Color, in 1925. Other collections published during the 1920s are Copper Sun (1927), The Ballad of the Brown Girl: An Old Ballad Retold (1927), and The Black Christ, and Other Poems (1929). McKay McKay was second only to Langston Hughes in his influence on the Harlem Renaissance. He is principally remembered for his realistic novel Home to Harlem (1928), primarily because its portrayal of black life prompted sharp criticism from W. E. B. Du Bois and Alain Locke. Praise for the novel was widespread; it was awarded the medal of the Institute of Arts and Sciences. McKay, who had immigrated to the United States in 1914 from Jamaica, returned to Jamaica in 1922. His poetry volumes published in the 1920s are Spring in New Hampshire and Other Poems (1920) and Harlem Shadows (1922). He was posthumously proclaimed national poet of Jamaica. Toomer Toomer, though not as influential as other participants in the movement, was a creative force with his remarkable first novel, Cane (1923). The work, generally considered the first novel of the Harlem Renaissance, was a series of stories and poems held together by thematic similarities and a poetic style. Women Writers The contributions of women writers, important in the movement during their time, have lately been rediscovered. Fauset was editor of The Crisis, the journal of the NAACP. In that role she published much of the earliest and best work by Harlem Renaissance writers. Her own 1920s novels--This is Confusion (1924) and Plum Bun (1928)--were influenced by realism. By the time of her death in 1961, she had published more novels than any other Harlem Renaissance writer. Hurston's best-known work and first novel, Their Eyes Were Watching God, was published in 1937, but her flamboyant personality and impressive early works made her a memorable figure in Harlem during the renaissance. Larson, like Toomer of mixed racial heritage, frequently dealt with issues of identity. Her best-known works, Quicksand (1928) and Passing (1929), led to her receiving the Harmon Medal in 1929 and a Guggenheim Fellowship in 1930, the first black woman so honored in creative writing. … Termination The movement began to lose its energy with the Great Depression, when many of the black publications folded and as many as 25 percent of Harlem's residents were unemployed. Eventually artistic fervor gave way to social anger, and by the mid 1930s the level of artistic production among writers associated with the movement had dwindled significantly. Among the many talented writers of the period, only Langston Hughes and Zora NealeHurston enjoyed general readership into the 1940s. FURTHER READINGS The Harlem Renaissance: An Historical Dictionary of the Era. (Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Press, 1984); Nathan Irving Huggins, Harlem Renaissance (New York: Oxford University Press, 1977); Huggins, ed., Voices from the Harlem Renaissance (New York: Oxford University Press, 1995). Source Citation: "Harlem Renaissance, 1925-1935." DISCovering U.S. History. Online Edition. Gale, 2003. Discovering Collection. Thomson Gale. 20 November 2006 <http://galenet.galegroup.com/servlet/DC> Document Number: CD2104240002 Jessie Fauset, Langston Hughes, Zora Neale Hurston (left to right) Jessie Fauset, Langston Hughes and Zora Neale Hurston, photograph. Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, The New York Public Library/Art Resource, NY. Reproduced by permission. Source Citation: "Jessie Fauset, Langston Hughes, Zora Neale Hurston (left to right)." Fauset, Jessie, Langston Hughes and Zora Neale Hurston, photograph. Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, The New York Public Library/Art Resource, NY. Reproduced by permission. Discovering Collection. Thomson Gale. 20 November 2006 <http://galenet.galegroup.com/servlet/DC> Document Number: CD2210019419 Incident Countee Cullen Once riding in old Baltimore, Heart-filled, head-filled with glee, I saw a Baltimorean Keep looking straight at me. Now I was eight and very small, And he was no whit bigger, And so I smiled, but he poked out His tongue, and called me, "N*****." I saw the whole of Baltimore From May until December; Of all the things that happened there That's all that I remember. Selected Recordings: Until the advent of the compact disc, the recordings of early blues greats such as Bessie Smith were difficult to find. Since the late 1980s, however, record companies have been actively re-releasing the work of many blues artists as well as producing some excellent blues anthologies. Check your local library in the folk section. Some suggested blues songs/artists from the 1920s and 1930s include: "Stack O' Lee Blues" by Mississippi John Hurt "Matchbox Blues" by Blind Lemon Jefferson "Cross Roads Blues" by Robert Johnson "Love in Vain" by Robert Johnson "Sweet Home Chicago" by Robert Johnson "Statesboro Blues" by Blind Willie McTell "Prove It On Me" by Ma Rainey "Downhearted Blues" by Bessie Smith Selected Hughes' Blues Poems: "Blues Fantasy" "Bound No'th Blues" "Evenin' Air Blues" "Hard Daddy" "Hey! Hey!" "Homesick Blues" "Midwinter Blues" "Misery" "Po' Boy Blues" "Song for a Banjo Dance" "The Weary Blues" "Young Gal Blues"