Examples of OER reuse - University of Leicester

advertisement

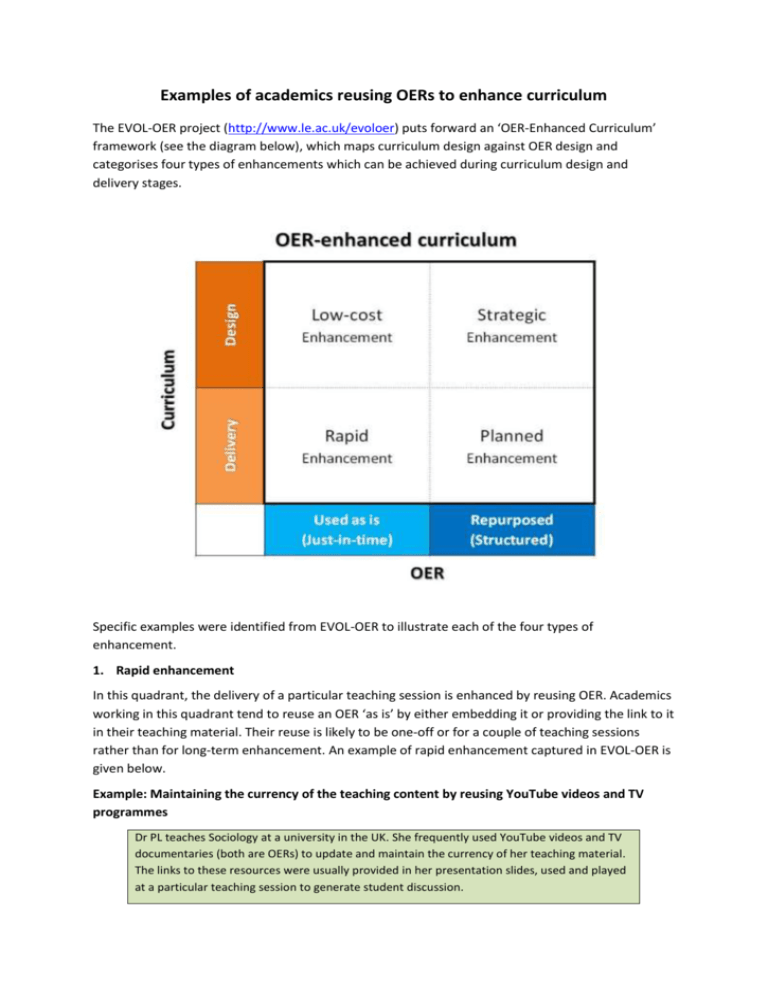

Examples of academics reusing OERs to enhance curriculum The EVOL-OER project (http://www.le.ac.uk/evoloer) puts forward an ‘OER-Enhanced Curriculum’ framework (see the diagram below), which maps curriculum design against OER design and categorises four types of enhancements which can be achieved during curriculum design and delivery stages. Specific examples were identified from EVOL-OER to illustrate each of the four types of enhancement. 1. Rapid enhancement In this quadrant, the delivery of a particular teaching session is enhanced by reusing OER. Academics working in this quadrant tend to reuse an OER ‘as is’ by either embedding it or providing the link to it in their teaching material. Their reuse is likely to be one-off or for a couple of teaching sessions rather than for long-term enhancement. An example of rapid enhancement captured in EVOL-OER is given below. Example: Maintaining the currency of the teaching content by reusing YouTube videos and TV programmes Dr PL teaches Sociology at a university in the UK. She frequently used YouTube videos and TV documentaries (both are OERs) to update and maintain the currency of her teaching material. The links to these resources were usually provided in her presentation slides, used and played at a particular teaching session to generate student discussion. Sociology is a dynamic and fast moving subject. For PL, there is a need for constantly incorporating new materials to maintain the currency of her teaching content, as she explained: “Because we’re looking at societies, and things change, and we use current examples in our teaching. I would say that’s quite common not just across this university but across sociology more widely as a discipline.” “We constantly use new materials and new ideas, incorporating those. It’s not unusual in sociology for something to appear in a newspaper on a Monday morning, and it turns up in a Tuesday class.” PL has already used a lot of e-learning resources to enhance her teaching material before OER comes into being. To her OER is just another source of e-learning materials which she can draw on, as she concluded, “My daily practice is about looking for teaching materials that might be relevant…OER is just a different resource [e-learning resource] you can draw on.” 2. Planned enhancement In this quadrant academics reuse OERs for the same purpose as those in the rapid enhancement, but the OERs are tweaked or repurposed to some extent to make them more suitable for the teaching context rather than just being reused ‘as is’. A couple of examples of planned enhancement were identified by EVOL-OER. Example 1: Localisation as a way of reusing GC works for the Staff Development Unit at a university in South Africa. Her role involves promoting open content, openness and sharing across her institution. She delivers workshops and seminars to staff members from different faculties and recommends OERs which the faculty members can draw on. Part of her job involves searching for and finding OERs in different subject areas, and compiling all these resources in a presentation which she gives to the faculty members. GC used many OERs to develop her presentations. One thing she did quite often was to localise these resources to make them more suitable and specific to the African context, as described by her: “Quite often we would take the image and then adapt it, especially that the African context is a little different to UK context or American context…So it’s always to make it more local and specific.” She also reused her own slides or slides created by her colleagues quite often. When delivering a presentation to a new group of staff, she remixed content taken from various previous presentations (which are OERs), and supplemented them with new content. She stated: “Because often we will have some slides that we used previously that we can draw on, we can adapt them and upgrade them. Also what we will often need to do is that we go and search for new content or examples, and add those in.” Example 2: Providing “wrapping” information to OERs Dr JG teaches Law at a university and Dr PJ teaches Criminology at a Further Education College in the UK. Both reused OERs to support their teaching. These OERs were embedded in their teaching material without any change, but they provided some “wrapping” information to these resources, such as guidance for their students to know about the context and relevance of the OERs to their course, and how the students could use these resources for their study. PJ described his experience as follows: “Actually use ‘as is’, but would give instructions to the students on how to use them. The main OERs that I’ve used are the ones I get from the OU [the Open University in the UK]. They’re like almost complete modules. Then I would give students the instructions so that they would read from 1.1 to 1.3 rather than doing the whole thing.” Example 3: Creating resources by taking ideas from other OERs ‘Copying’ styles from other OERs and creating resources of their own is another way of reusing. One interviewee PJ described: “The things that I’ve seen on VoiceThread are extremely useful. I was copying their style. So I didn’t repurpose a specific resource. It was more a question to see what people have done on VoiceThread, and using their approach of creating my own.” GC, a colleague from South Africa adopted the same approach: “In a lot of the presentations, we do have video clips. We need some South African versions. So we’ve used ideas that other people have used in their videos, then we just put them into South African context.” 3. Low-cost enhancement In this quadrant, OERs are embedded in the curriculum design at minimum cost. The purpose of embedding OERs in the curriculum is for long-term enhancement rather than just for supporting certain teaching sessions. A number of examples of low-cost enhancement were identified in the EVOL-OER project in which the academics reused OERs ‘as is’ or with minor changes. Example 1: Creating courses by reusing open content created for adult learners The Bridge to Success (B2S, http://b2s.aacc.edu/) project developed two open courses: Learning to Learn and Succeed with Maths. The courses aimed at helping adult learners in the USA to successfully transit into college environment. The course content has been embedded in a wide range of courses and programmes offered by a number of partner colleges in the USA. The B2S content has been delivered in face-to-face, online or blended teaching. The manager to the B2S project PL elaborated: “The content can be used completely independently by students online. It can be used completely online by students plus they have an online tutor. Or it can be classroom based. And all of those things are happening.” Data gathered from the pilot stage showed that the partner colleges have used B2S content in different ways. Some used all the content in its entirety. Some picked and used certain units from the two courses, but the units they chose to use remained unchanged. PL summarised, “Some of them might use all of the courses they’ve been presented with. Some of them have just picked certain units. So a college might decide that their nursing students really need Unit 3, 4 and 7 of the Maths course, but all their students are going to do all of the Learning to Learn… We don’t yet have anyone modified against the content.” Example 2: Reusing research article OERs to demonstrate academic writing JM works for the English Language Teaching Unit at a university in the UK. His unit teaches many in-session students. They are the international students who are already enrolled in their degree programmes but want to enhance their English in terms of academic writing. One of the challenges faced by his unit is to find source materials which can be used as academic models to show students what academic writing is. His unit is in need of these writing materials that are not designed for language teaching, but can demonstrate how reports and dissertations are written in various subjects such as Psychology, Engineering and Law. Another challenge is that some of the in-session classes become very big particularly during the summer. There is a need for his unit to publish their teaching material online so that the students can access the material after class. OERs can be very useful to meet these challenges, as JM stated: “I’ve been looking at how we can find a way to design our materials around sources which are not copyrighted. That’s why we started to look for academic source materials which are available largely for us to adapt.” JM started using open research paper (which themselves are OERs) to demonstrate the students what constitutes academic writing. He took sections out of an open research article and used those sections exactly as they were in his teaching material, as JM described: “I might only be interested in the paragraphs that describe the methodology if it’s a medical research paper and I have some medical students. I try to show them what language they need and the approach they need to describe their experimentation. Then I might just take a few paragraphs from that. The rest of the article will be deleted. So it’s taking things out of from its original context. Isolating them and highlighting them is a big part of what we do.” He felt that reusing these articles ‘as is’ maintained the integrity and authenticity of the material, which is very important for language teaching and learning, as JM explained, “I don’t change the language because that defeats the purpose of they are being authentic…It is important to me that it’s a genuine academic research.” Some of the articles were slightly modified to make them more suitable for the teaching purposes. For example, keywords were taken out from a paragraph and students were asked to put those words back in during a teaching session. Example 3: Developing Study Skills OERs for research students Dr VS works for the Library at a university in the UK. She was involved in producing a set of OERs on Study Skills. These OERs were adapted from OERs from a number of UK-based institutional repositories with minor changes, such as changing context, updating content in a minor way, adding indices, removing or splitting up activities, and changing format. She was able to complete the task within three months. Being able to reuse existing OERs had made this possible, as she reflected: “If we start writing from scratch, it’s just not possible. It wouldn’t be possible otherwise.” These OERs are beginning to be embedded in the teaching and training programmes offered to the research students within her institution. One way, as VS suggested, is to link these OERs to Action Planner – a tool that assesses a student’s research skills and provides recommendations on what resources and training programmes this student could take and use. Example 4: Providing e-books and OERs to supplement teaching material There is a lack of resources in Africa. Some African institutions provided additional learning materials including e-books and OERs to students to supplement their study. These resources were normally provided in their original forms without any changes. They were organised into categories and provided to students via CDs or DVDs. Some of these resources were core to the teaching programmes; some are additional. Students can treat these resources the same way as those recommended by a lecturer in the usual course reading list. One case is that the Library of the Bunda College of Agriculture in Malawi provided e-books and OERs to the PhD students studying the Aquaculture programmes. These resources were made available to the students in CDs, each containing a mix of materials, articles, papers, guides and open access journals, organised into seven categories. The Chancellor College of the University of Malawi provided e-Books and OERs to the students studying the Teacher Training programmes. Each student received a CD containing 50 digital textbooks and 40 quality OERs. The Medical School of the University of Botswana developed a pre-clinical course on Foundations in Medicine, by drawing on materials from a range of open sources, including MedEd Portal, John Hopkin’s Bloomberg School of Public Health, Health Education Assets Library (HEAL), Open.Michigan, Medical School & School of Public Health, Tufts Open Courseware School of Medicine and MIT Health Sciences and Technology. These resources were delivered to their students via DVDs, each containing material in three categories: images and animations, courses and lecture notes, and online journals. 4. Strategic enhancement In this quadrant, OERs are embedded in the curriculum design formally in a structured way. The academics working in this quadrant tend to repurpose OERs for the development of an open course, an open textbook, or a set of open resources, which then become the core resources for others to reuse. Some examples of strategic enhancement were identified in EVOL-OER. Example 1: Developing a Sociology curriculum by incorporating OERs in Criminology Dr PL teaches Sociology at a university in the UK. Sociology draws on a number of disciplines in Social Sciences, such as public policy and criminology. There is a need to draw on resources from these disciplines to enhance and enrich a sociology curriculum. OERs can be useful for this purpose. PL reused a number of Criminology OERs for the development of a Sociology module. ‘Pick and mix’ was the way how she reused these resources, as PL described as follows: “This really is a summary which I took from the State Crime module [OER]. The six ideas about what state crime is was from there. The stuff around corruption is from State and Corporate Crime [OER]. So this small part of the lecture actually comes from that module.” “It’s more a question of pick and mix really. Taking bits from here, bits from there, and putting them all together.” Example 2: Reusing multimedia OERs for teaching Arts and Design DR CF teaches Arts and Design at a university in the UK. He has reusd a lot of OERs, especially multimedia OERs for teaching. There is strong sense of reuse in Arts and Design, as elaborated by CF: “There is obviously a history in Arts schools of reuse. We reuse ideas. Artists always reuse other artists’ ideas, montage together different fragments. There is the notion of collage, so taking something existed and making it into something else. So there is a culture of reuse and reworking. And also Found footage is quite an arts term. This is the interest in reusing video OER. Artists used videos, films that already exist, and rework them into new works.” CF described the way how he repurposed multimedia OERs such as videos as follow: “The OER impact report was released and they produced a very lovely video, a long vide. If you’re giving a presentation, you don’t necessarily want to play the whole thing. What you want to do is to take a snippet of that, and put with another snippet of something else. So in a way that’s a montage element of video.” Subjects in Arts and Design are very practical-based. Teaching and learning have to be done physically in a studio environment. With video OERs showing students the arts processes, students can watch them before they come to the studio. They can then discuss their ideas during the practical sessions rather than focusing on learning the processes. Using OERs has opened up new ways of interacting and engaging with students. CF described how using OERs has transformed the teaching and learning in Arts and Design as follows: “Learning and teaching [Arts] is all about making physical. You have to almost be there. And also it’s not so generic. It’s quite individual and personal… So he’s [the lecturer] now working on digital pieces of materials and discussing that with the students. So he’s seen the change from the student coming in with ideas in their heads and trying to communicate them… This is like a new dimension within that particular aspect of studio experience.” Example 3: Developing an open course on Laboratory skills Dr VR teaches subjects in Health Sciences at a university in the UK. Searching and reusing OERs have become fully embedded in her academic practice. When there is a need for updating existing course material or developing material for a new course, the first thing VR does is to look for what resources are already available - ‘the harvest’ as described by her. VR and her colleagues identified that a large numbers of new students who are entering Bioscience and Medical Science programmes in her institution are with no prior laboratory experience. She decided to develop an open course on Laboratory Skills by drawing on OERs from a range of repositories. This course will be used for teaching lab skills to the first-year students in Health Sciences within her institution from September 2012. The course will also be used by second and third year students for reviewing the lab skills in their own time. Example 4: Developing open resources for Teacher Education programmes TESSA (Teacher Education in Sub-Saharan Africa, http://www.tessafrica.net/) developed a set of open resources for improving teacher education in Sub-Saharan Africa. TESSA materials had been adapted and reused by a wide range of Teacher Education programmes offered by different types of institutions in Africa in a variety of different ways. TESSA manager JC explained: “What we measure as TESSA success is the multiplicity in the ways in which they [TESSA materials] were reused. There isn’t any one way. There isn’t any one mode. There isn’t even one kind of institution that is using them. There isn’t even one course that has been reused on.” TESSA categorised how their OERs were reused across different teacher education institutions along a continuum. At one end of the continuum is guided use, and the other end is structured use. Guided use refers to when TESSA materials are used loosely at the level of individual choice among the teacher educators. Structured use refers to when TESSA OERs are embedded in the curriculum in a highly structured way. Two examples of structured use for long-term enhancement are given as follows. At the Open University of Tanzania, TESSA materials have been written into the course material and delivered as part of the Diploma for Primary Education. The Open University of Sudan has a huge distance learning teacher education programme. TESSA materials have been written into the teaching guidance for the supervisors to this programme. Example 5: Developing an open textbook on Communication Skills The Bunda College for Agriculture in Malawi developed a Communication Skills textbook by repurposing various open resources. This textbook OER has been formally embedded in the institution’s curriculum. The textbook has been subsequently reused and adapted by the University of Jos in Nigeria for the development of their own Communication Skills textbook for trade union leaders. This new textbook included sections taken from the original textbook and used ‘as is’; sections modified from the original textbook, for instance, replacing examples with trade union specific scenarios and examples; and new materials adapted from other open sources. The ‘OER-Enhanced Curriculum’ framework has been incorporated into the Carpe Diem (http://www.le.ac.uk/carpediem) learning design workshops developed by Leicester to guide academics how to use and reuse OERs to enhance curriculum design and development. The framework together with its associated examples could also be used and significantly enhance OER utilization across other institutions.