bradst

advertisement

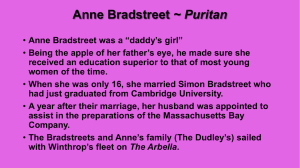

Sharon D. Smith Dr. Smolinski Eng. 3800 March 13, 2001 ANNE BRADSTREET: The Ambiguous Puritan “The world no longer let me love/My hope and treasure lies above” (Hensley, 57-58). This quotation represents one of the most prevalent themes in all of Anne Bradstreet’s poetry and meditations. She essentially focuses on personal experiences involving her family, society, and her own spiritual development. In “Upon the Burning of Our House” and the three poems in regard to the death of her grandchildren, Bradstreet realizes her own shortcomings and tries to deal with them in an image-filled, dissociating manner. Although Bradstreet is greatly grieved by her losses, she relies heavily on the Puritan values of the time to deal with the tragedies in her life. The Puritan value system shapes her writing, however, Bradstreet questions it through very subtle comments. In “Upon the Burning of Our House,” Bradstreet deals with her attachment to earthly possessions when she says, “here stood that trunk, and there that chest/there lay that store I counted best” (29-30). Throughout the poem, Bradstreet contemplates how fire consumed her home and how she will never be able to enjoy it or the things inside it again. She eventually realizes that while these are earthly things, there is a far better “house” or reward in Heaven. When Bradstreet says, “Thou hast an house on Smith 2 high erect, framed by that mighty Architect” (47-49), she comes to terms with the fact that the things of this world are not comparable to what exists in Heaven. Bradstreet goes on to say, “there’s wealth enough, I need no more/Farewell, my pelf, farewell my store” (55-56). In these lines, Bradstreet has abandoned her desire for earthly goods and has moved into an awakening of her spirit. This can be clearly seen in her concluding lines, “My hope and treasure lies above” (58). Although she does not claim that she is going to Heaven, she does assert that she is hopeful to be among those who are chosen to go to Heaven. Bradstreet has accomplished three things in this poem. First, she has identified her attachment to material things. pleasant things in ashes lie” (31). “My Second, Bradstreet has realized that far greater and more permanent things await her. “With glory richly set furnished/stands permanent though this be fled” (49-50). The third thing Bradstreet has done has been to tie both her material attachment and her belief in divine rewards together with a variety of images. When she says, “sorrowing eyes” (26) and “mold’ring dust” (43), Bradstreet expresses her sorrow for the things she has lost. When she says, “my hope and treasure” (58), Bradstreet expresses her faith in God and His divine intervention. She goes on to say, “it was His own, it was not mine/far be it that I should repine” (21-22). In the poem concerning the death of her grandchild, Smith 3 Elizabeth, Bradstreet equates nature with Elizabeth’s death. She speaks of things in nature such as flowers, grass, and fruits having a short existence. date” (18). God. “And buds new blown to have so short a Bradstreet goes on to express her continued faith in “Is by His hand alone that guides nature and fate” (19). It is here that Bradstreet accepts the loss of her grandchild as part of God’s plan. “Blest babe, why should I once bewail thy fate...sith thou are settled in an everlasting state” (10-12). The poems concerning the death of Bradstreet’s grandchildren, Anne and Simon, are also expressions of Bradstreet’s reliance on nature to come to terms with death. Bradstreet uses terms such as “withering flower” (“Anne,” 14), “brittle glass” (“Anne,” 16), and “three flowers, two scarcely blown” (“Simon,” 7). Bradstreet’s purpose for writing these poems is simple. It is a way to come to terms with her dependency on the impermanent objects in her life and to raise her consciousness to more divine things such as redemption and salvation. How oft with disappointment have I met, When I on fading things my hopes have set. Experience might ‘fore this have made me wise, To value things according to their price. (“Anne,” 8-11) Bradstreet writes these lines after the death of two of her grandchildren and of course, the burning of her house three years earlier. She seems upset to have allowed herself to become so attached to her personal items and her grandchildren. “More fool then I to look on that was lent/as if mine own, when thus Smith 4 impermanent” (“Anne,” 18-19). She is realizing that all things in life are meant to come to an end and that she must accept it. She is also realizing that the things she have now are only temporary. In the poems regarding her grandchildren, Bradstreet naturally acknowledges her grief. She speaks of her “throbbing heart”(“Anne” 22), “withering flower” (“Anne,” 14), and “bitter crosses” (“Simon,” 14), but she reconcifles her grief by saying that her grandchildren are in a far better place. She speaks of “everlasting state[s]” (“Elizabeth,” 12), “endless bliss” (“Anne,” 23), and “endless joys remain” (“Simon,” 16). These signify that they are in Heaven and that hopefully Bradstreet will see them again (“Anne,” 20). Bradstreet’s acceptance of the things she has lost throughout her lifetime, however, is not totally by choice. “With dreadful awe before Him let’s be mute/such was His will, but why let’s not dispute” (“Simon,” 9-10). During Bradstreet’s time, one of the Puritan values was to be accepting of God’s will and not question it. rejoice instead. Bradstreet was expected not to grieve, but In Hensley’s forward, Adrienne Rich writes: No event so trivial that it could not speak a divine message, no disappointment so heavy that it could not serve as a “correction,” a disguised blessing. (X) It was not a part of Puritanism to value worldly goods, but to have one’s heart and mind set on God and His heavenly rewards. Perhaps Bradstreet wrote these selections to express that she had Smith 5 had a conversion experience so that she may be called one of God’s elect, therefore, having a seat in Heaven, according to Puritan values. Perhaps Bradstreet wrote these poems to secretly express her desire to challenge the Puritan value system. This can be clearly seen when Bradstreet says, “Cropt by th’ Almighty hand; yet is He good” (“Simon,” 8). She goes on to say, “Let’s say He’s merciful as well as just” (“Simon,” 12). Bradstreet questions the will of God. In these lines, The implication is that God cannot be a good God if He takes the lives of small children. Yet, Bradstreet cannot explicitly say this in her poetry without the possibility of being condemned. Again, she reconciles her grief by saying that God will reward her later (“Simon,” 13). Whatever reasons Anne Bradstreet had for writing these poems, it is evident that she cares for her family. It is also evident that despite her losses, she still loves God and respects His will. In a book on sentamentalism, Lauren Berlant writes: The failure to cultivate intellect, talent, or simply self-expression has a sublime range of effects on women...the woman becomes a...slave to surfaces and form, dedicating herself to policing [her own] adherence to rule while often becoming massively hypocritical. (Samuels, 272). This statement clearly supports the idea that Bradstreet is writing as a means to help her deal with her losses without completely sacrificing her religious beliefs. in doing this? Has she succeeded The answer cannot be simply stated. However, she has succeeded in expressing her love for herself and for God. Smith 6 Bibliography Berlant, Lauren. “The Female Woman.” The Culture of Sentiment: Race, Gender, and Sentimentalism in 19th Century America. Ed. Shirley Samuels. Oxford University Press, 1992. Rich, Adrienne. “Anne Bradstreet and Her Poetry.” Ed. Shirley Samuels. The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 1967. Samuels, Shirley, Ed. The Works of Anne Bradstreet. The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 1967.