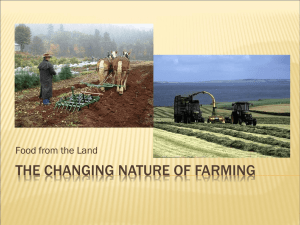

2. Organic agriculture: concepts and policies

advertisement