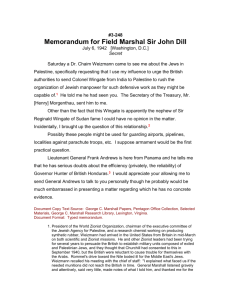

orde wingate and the british army

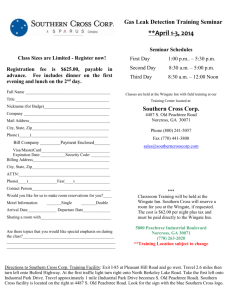

advertisement