Choosing Multicultural Children`s Books

advertisement

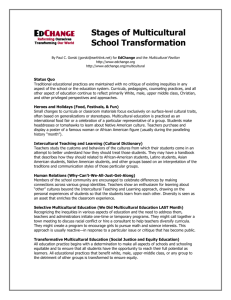

Multicultural Children’s Books Part One: Choosing a multicultural children’s text Multicultural children’s literature offers readers the opportunity to go beyond the surface-level learning of facts, foods and festivals about different cultures and to gain real insight as to how people around the world actually live and the relationships and experiences they have. This links to the Curriculum for Excellence capacity Responsible Citizen - to not only understand and respect other cultures and beliefs but to also gain a greater knowledge of the world and Scotland’s role in it. In the increasingly diverse classroom, educators have a responsibility to provide reading experiences that are reflective of learners’ backgrounds and culture (Yokota, 1993). Yet choosing a text can be a stressful task, with many teachers concerned they will choose a book that reinforces stereotypes and is in some way offensive. The following criteria are not intended as rules to be adhered to, but a framework of areas to consider when selecting and discussing a text: Authenticity and Accuracy There is ongoing debate as to author/illustrator authenticity in multicultural children’s literature, and learners could join in on this debate. While choosing an ‘authentic’ author/illustrator may be preferred, that is one who is writing from inside the culture being portrayed, this isn’t always possible. Ensuring the text is culturally accurate and rich in cultural detail however, is important. Through literature being culturally conscious and accurate, readers should gain a real insight into life in the culture they are reading about. Perspective The book should be told from an inside perspective – that is from the point of view from someone who is a member of the cultural group being portrayed. A text where the British protagonist is visiting a different culture would be unlikely to offer the same insight and empathy as one where the protagonist is inside the culture being described. Characters, setting and plot The characters should be well-rounded, and their actions agreed with and recognised by the culture being portrayed. The setting should be realistic and not stereotypical, showing the richness and depth of the culture. The plot should be realistic and believable. Language and illustration The language used should be an authentic portrayal of how the characters would speak and not a stereotype of how an outsider thinks they would speak. Look out for ‘loaded’ words - that is words that have insulting connotations, for example ‘primitive’. The richness of the culture should be evident in the illustrations, with characters illustrated in a non-stereotypical manner and not as caricatures. Levels of multiculturalism Multicultural children’s literature provides a space for readers to consider global socio-political issues, and it is useful to place your chosen literature on Banks’ (2001) Levels of Multicultural Model: Level 1: A Contributions Approach – Where festivals, food and clothing are explored, but stereotypes aren’t necessarily challenged, and learners are looking from an outside, rather than an inside perspective. Level 2: The Additive Approach –While there may be folktales from different cultures and authors from different ethnicities, these aren’t embedded into the curriculum, but rather added on as afterthought. Level 3: The transformative Approach – Where readers’ opinions are challenged, and literature from a variety of different perspectives are read and discussed. Level 4: The Social Action Approach – Where teachers empower students and support them to reflect on socio-political issues and take action for themselves. Literature at levels three and four of the model encourages learners to take control of the curriculum and their own learning, and organisations like Amnesty International, British Red Cross and Oxfam provide a plethora of resources to help learners to bridge the gap between literature and action. It is at these higher levels we see the transformative power of children’s literature - to challenge discrimination, build bridges and to instigate social change. Bibliography: Banks, J. A. and Banks C. M. (2001) (Eds) Handbook of research into multicultural education. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. Botelho, M.J. and Rudman, M.K. (2009) Critical Multicultural Analysis of Children’s Literature. Abingdon: Routledge. Education Scotland (online) ‘The Purpose of the Curriculum’ at http://www.educationscotland.gov.uk/thecurriculum/whatiscurriculumforexcellence/th epurposeofthecurriculum/index.asp (last accessed 09 May 2013) Gopalakrishnan, A. (2011) Multicultural Children’s Literature: A Critical Issues Approach. London: Sage. Mendoza, J. and Reese, D. (2001) Examining Multicultural Picture Books for the Early Childhood Classroom: Possibilities and Pitfalls. Early Childhood Research and Practice, Vol 3 (2) at http://ecrp.uiuc.edu/v3n2/mendoza.html (last accessed 09 May 2013) Short, K.G. (2011) ‘Building Bridges of Understanding through International Literature’ in Bedford A. W. and Albright, L.K (Eds) (2011) A Master Class in Children’s Literature: Trends and Issues in an evolving field. National Council of Teachers. Yokota, J. (1993) ‘Issues in Selecting Multicultural Children’s Literature’ in Language Arts, 70 (3), pp. 156-167. Part two: A Critical Reading of Multicultural Children’s Literature Although multicultural children’s literature can offer an insight into different cultures, they don’t do all of the work by themselves – they act as a springboard to discuss the social issues present in the text. A critical reflection provides the opportunity to discuss the ideologies in the text and in society, why and where certain books have been published, and the intricate relationship between culture and power. Critical literacy is a relatively new concept with no precise definition and with its roots found with Paulo Freire and his renowned phrase ‘reading the word, reading the world’. Freire argued that if ‘people perceive critically the way they exist in the world with which and in which they find themselves; they come to see the world not as a static reality, but as a reality in progress, in transformation’ (1970, p. 64). This concept can be readily applied to multicultural texts: teachers, as facilitators, should encourage students to problematize texts and to challenge accepted ideologies, and empower them to call for change. Taking a critical approach is not just for older learners; even children in the early years should be encouraged. Children start school with their own ideas of social status reflected in the literature they read, the television they watch and the games they play: who is good/bad and who has power, knowledge and authority (Comber, 2001, 2003). The role of the teacher then is to build on this existing knowledge. Luke and Freebody (1999) point out that texts are never neutral, they inevitably represent specific view points while silencing others. To prompt a critical reading of a text, the following questions are a good starting point: ‘Who has the power in this story? What is the nature of their power, and how do they use it? Who has wisdom? What is the nature of their wisdom, and how do they use it? Whose voices are heard? Whose are missing? What do this narrative and these pictures say about race? Class? Culture? Gender? Age? Resistance to the status quo?’ (Reese and Mendoza, 2001, online) Similarly, reading multiple texts alongside each other while also consulting nonfiction sources helps readers gain a more accurate perspective, and to see how they are being positioned. Multiple readings encourage learners to consider multiple perspectives and refrain from judgement. A critical reading doesn’t necessarily have to be serious and without fun, and humour and creativity provides a memorable learning experience for both the teacher and learner. There are numerous activities to engage children in a critical reading of texts: McGonigal and Arizpe (2007) used a detective theme, where children were encouraged to ‘look for clues’ and complete speech bubble activities. From annotating copies of texts, the juxtaposition of multiple texts and multimodalities such as drama, dance and digital technologies to children re-writing the stories themselves – the possibilities are endless. To read more, my reflective blog for ‘Texts for Diversity: language across learning for children with EAL’, an optional course in Glasgow University’s MEd in Children’s Literature and Literacies is online at www.ealreflections.wordpress.com. Bibliography: Botelho, M.J. and Rudman, M.K. (2009) Critical Multicultural Analysis of Children’s Literature. Abingdon: Routledge. Comber, B. (2001) Critical Literacy: What Is It, and What Does It Look Like in Elementary Classrooms? School Talk: Between the Real and the Ideal World of Teaching at http://resources.curriculum.org/secretariat/files/Nov29CriticalLiteracy.pdf (last accessed 09 May 2013). Comber, B. (2003) ‘Critical literacy: What does it look like in the early years?’ in Hall, N., Larson, J. and Marsh J. (eds) Handbook of Early Childhood Literacy. London: Sage. Farrell, M., Arizpe, E. and McAdam, J. (2010) Journeys across visual borders: Annotated spreads of 'The Arrival' by Shaun Tan as a method of understanding pupils' creation of meaning through visual images. Australian Journal of Language and Literacy, 33 (3) pp. 198-210. Gopalakrishnan, A. (2011) Multicultural Children’s Literature: A Critical Issues Approach. London: Sage. Mendoza, J. and Reese, D. (2001) Examining Multicultural Picture Books for the Early Childhood Classroom: Possibilities and Pitfalls. Early Childhood Research and Practice, Vol 3 (2) at http://ecrp.uiuc.edu/v3n2/mendoza.html (last accessed 15 April 2013). McGonigal, J. and Arizpe, E. (2007) Learning to Read a New Culture: How Immigrant and Asylum Seeking Children Experience Scottish Identity through Classroom Books at http://www.scotland.gov.uk/Publications/2007/10/31125406/0 (last accessed 07 May 2013) Short, K.G. (2011) ‘Building Bridges of Understanding through International Literature’ in Bedford A. W. and Albright, L.K (Eds) (2011) A Master Class in Children’s Literature: Trends and Issues in an evolving field. National Council of Teachers. Souto-Manning, M. (2009) Negotiating culturally responsive pedagogy through multicultural children’s literature: Towards critical democratic literacy practices in a first grade classroom. Journal of Early Childhood Literacy. Vol 9 (1) pp. 50-74. Yokota, J. (1993) Issues in Selecting Multicultural Children’s Literature. Language Arts, 70 (3), pp. 156-167.