CHAPTER 11: FIGURES OF SPEECH: METAPHOR AND SIMILE

advertisement

Introduction to

semantics and

translation

by

Global Bible Translators

Katharine Barnwell

Summer Institute of Linguistics

본 교재는 고신대학교 ‘성경번역학’ 강의를 위해 저자의 허락을 얻어 제작된 축약본 입니다

GBT/SIL 조광주

1980 Summer Institute of Linguistics, Inc.

1

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This course is based on the theory and principles of Bible translation presented by Beekman and Callow,

in Translating the Word of God and Nida and Taber, in The Theory and Practice of Translation.

It also incorporates insights from Beekman and Callow, The Semantic Structure of Written

Communication (pre-publication edition).

These and other sources are gratefully acknowledged at the relevant places in the text.

Many of the examples are drawn from experience of Bible translation projects in Nigeria. Staff and

students at the British SIL over the past few years, as well as other colleagues, have also contributed

examples in various languages, and these, too, are acknowledged in the text, as far as possible, with much

appreciation to all who have shared their ideas and experience.

I am especially grateful to John Callow and Pam Bender-Samuel for their helpful comments and

suggestions on the text, and to Liz Crozier, Yvonne Stofberg and David Spratt for helping to proofread

the final manuscript.

Katharine G.L. Barnwell

Horsleys Green, 1980

NOTES AND ABBREVIATIONS

The following abbreviations are used to refer to Bible versions:

GNB - Good News Bible – quotations are from the 1976 British usage edition

JB - Jerusalem Bible

JBP - J.B. Phillips' version

KJV - King James Version (Authorized version)

NEB - New English Bible

NIV - New International Version

RSV - Revised Standard Version

원저자에 대하여

Katy Barnwell has served with SIL since 1963 in Nigeria and Africa Area, and from 1989 to 1999 in the

International Translation Department at Dallas. In Nigeria she was seconded to the Nigeria Bible

Translation Trust and was extensively involved in training Nigerian translators and consultants. She

received her Ph.D. in Linguistics from the School of African and Oriental Studies and University College,

London, in 1969.

차 례

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ............................................................................................. 2

NOTES AND ABBREVIATIONS .................................................................................. 2

원저자에 대하여 ............................................................................................................. 2

차 례 ............................................................................................................................. 2

CHAPTER 1: WHAT IS LANGUAGE? ......................................................................... 3

CHAPTER 2: MEANING AND FORM .......................................................................... 5

CHAPTER 3: MEANING IN CONTEXT AND ‘CONCORDANCE’ ......................... 10

CHAPTER 5: COMPONENTS OF MEANING ............................................................ 14

CHAPTER 6: OTHER LEXICAL RELATIONSHIPS ................................................. 17

CHAPTER 9: TRANSFERRING LEXICAL MEANING FROM ONE LANGUAGE

TO ANOTHER ............................................................................................................... 18

CHAPTER 10: RHETORICAL QUESTIONS .............................................................. 29

CHAPTER 11: FIGURES OF SPEECH: METAPHOR AND SIMILE ........................ 33

CHAPTER 12: OTHER FIGURES OF SPEECH .......................................................... 36

CHAPTER 14: THE CONCEPT .................................................................................... 42

CHAPTER 24: BIBLE TRANSLATION PROCEDURES ........................................... 43

2

CHAPTER 1: WHAT IS LANGUAGE?

1.1 THE FUNCTION OF LANGUAGE

What is the purpose of language? What do we use language for?

- to give information

- to obtain information

e.g., by asking questions

- to stimulate actions

e.g., by giving commands

or by making suggestions,

or just by saying something

which arouses a response

- to express feelings or emotions

e.g., by exclamations

or by poetry

- to establish a relationship with other people, or to

indicate and attitude

e.g., greetings, such as ‘hello’

In summary, the function of language is to communicate MEANING of various kinds. Words

are powerful tools for giving information and for stimulating reactions in other people

1.2 THE FORM OF LANGUAGE

There are, of course, other ways of communicating meaning:

e.g.,

traffic lights

international traffic signs

factory whistle (indicating the time to start or stop work)

gestures or mime

the dancing of bees which indicates where honey can be found

How is language different from these other systems of communication?

i. The use of VOCAL SOUNDS, i.e., sounds made with the mouth and other speech organs.

(Or of WRITING, which is another way of representing verbal sounds).

ii. The COMPLEXITY of the system—Language involves more than isolated signals, each with its

own fixed meaning. It involves a complex, interacting combination of signals which can be used in a wide

variety of situations. This makes possible the expression of fine distinctions of meaning, and also

discussion and explanation.

iii. Language is CREATIVE—Language is a system which allows for the expression of new ideas; it

is possible to say something which has never been said before, and to be understood. The system itself is

constantly developing and expanding. Thus, language may be described as an ‘open-ended’ system.

1.3 THE RELATION BETWEEN THE MEANING AND THE FORM OF LANGUAGE

Language therefore, is communication which involves:

A. MEANING

a message which is being

communicated

B. VOCAL SOUNDS

the sounds by which that message is

communicated

But sounds alone do not communicate. A language which is unknown to the hearer sounds to him like

a meaningless jumble of noise. The hearer cannot understand the meaning of those sounds unless he is

also familiar with the complex system by which, in that language, the sounds are linked with particular

meanings. Each language has its own distinctive systems for linking sounds with meanings. These

include:

3

a. Vocabulary — Each language has a large number of words, each of which conveys a meaning which

has been (unconsciously) agreed and accepted by speakers of that language. The meaning of each

word will, of course, vary according to the context in which it is used and the other words with which

it occurs. This inventory of words is sometimes referred to as the LEXICON or LEXICAL

INVENTORY of the language.

b. Grammar — Each language also has an accepted set of patterns for making meaningful utterances;

signals such as a certain word order, a particular intonation, or the presence of a “grammatical” word

(such as a preposition or conjunction) all convey particular meanings.

c. Phonology — Each language has a fixed number of phonetic sounds (e.g., a certain number of

vowels and a certain number of consonants). These sounds group together in regular and consistent

patterns to form the phonological units of that language. It is these phonological units which actually

give substance to (or “realise”) the lexicon and grammar of a language.

Thus, the relationship between the meaning and the form of language can, in a simplified way,

be diagrammed as follows:

Meaning

communicated by

LEXICON

GRAMMAR

Sounds

realised by

"FORM"

Thus, language can be viewed, from one perspective, as a complex of interrelated ‘levels’:

lexicon, grammar, and phonology.

1.4 MEANING IS UNIVERSAL, FORM IS DIFFERENT FOR EACH LANGUAGE

With very limited exceptions, it is possible to express the same meaning in any language. But the

particular form by which that meaning is expressed will be different in different languages.

Thus the diagram on the previous page can be summarised:

MEANING

(universal)

expressed by

FORM

(the unique patterns of a specific language)

4

CHAPTER 2: MEANING AND FORM

2.1 EXPLORING THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN MEANING AND FORM IN A LANGUAGE

2.1.1 ONE MEANING MAY BE EXPRESSED BY SEVERAL DIFFERENT FORMS

Even within one langua ge, it may be possible to express one meaning by several different forms; that is,

by using different grammatical patterns and/or different words.

e.g., (a) “Is this place taken?”

“Is there anyone sitting here?”

“May I sit here?”

2.1.2 ONE FORM MAY EXPRESS SEVERAL DIFFERENT MEANINGS

The meaning of a given form in a language is no t always the same. It may vary according to the context

in which it occurs, depending either on the situation in which the utterance is spoken, or on the linguistic

context, i.e., the other linguistic items with which it co-occurs.

e.g.,

(a)

He put the things on the table.

a mathematical table

a bus timetable

to table a motion

(b)

my car — i.e., the car which belongs to me (possession)

my brother — i.e., the brother to whom I am related (kinship)

my foot — i.e., the foot which is part of my body (part-whole)

my singing — i.e., (what/how) I sing (actor-activity)

my book — i.e., the book which belongs to me (possession)

or the book which I wrote (author creator)

or the book I am talking about now, as in “my book for review:

(item reference)

my village — i.e., the village I come from

my train — i.e., the train I plan to travel on

my route — i.e., the route I intend to follow

my word! — i.e., exclamation of surprise

Thus, WITHIN ONE LANGUAGE

ONE MEANING MAY BE EXPRESSED BY SEVERAL DIFFERENT FORMS

meaning

ONE FORM MAY EXPRESS SEVERAL DIFFERENT MEANINGS

form

2.4 IMPLICATIONS FOR TRANSLATION

The starting point of translation is a message. This message is expressed in a specific language, which is

called the SOURCE LANGUAGE (SL).

In translating, we are aiming to re-express that message in another language. The language into which the

translation is being made is called the RECEPTOR LANGUAGE (RL).

We have already seen that the FORM of each language is unique. Therefore translation will involve some

5

change of form. This does not matter provided that the MEANING of the message is retained unchanged.

Translation, therefore, involves TWO stages:

Stage 1: Analysing the meaning of the source message. In the Biblical context, this is referred to as

EXEGESIS.

Stage 2: Re-expressing the meaning as exactly as possible in the natural form in the receptor

language. This step is sometimes referred to as RESTRUCTURING.

Thus the translation process can be diagrammed as follows:

SOURCE MESSAGE

TRANSLATED MESSAGE

FORM

in the

SOURCE LANGUAGE

FORM

in the

RECEPTOR LANGUAGE

Discovering the

meaning (exegesis)

Restructuring

the meaning

MEANING

STAGE 1

STAGE 2

2.4.1 MEANING HAS PRIORITY OVER FORM

Sometimes translators try to transfer a message without changing the form. The result is often either a

translation which is impossible or difficult to understand, or one which even expresses wrong meaning.

For example, the expression “sons of the bridechamber” in Mark 2:19 (quoted below in section 2.5,

example (1)), was translated word-for-word into one language, and was understood by the hearers to

mean “the children which the bride had borne before her marriage,” a token of her fertility—an

interpretation which accorded with custom in that area.

In another language, the RSV rendering of Luke 2:5 “Mary was with child” was translated word-forword, “Mary kept all these things in her heart,” until it was realised that in Kilba ‘to keep in one’s heart’

is an idiom meaning ‘to bear a grudge’. So the verse had to be re-translated, “Mary kept on thinking about

these things.”

Other examples:

Gird up the loins of your mind KJV 1 Peter 1:13

Put a belt round the waist of your thoughts (early Igbo version)

Put on bowels of mercies KJV Colossians 3:12

(compare J.B. Phillips’ version: Be merciful in action)

In these instances, keeping the FORM of the source message resulted in wrong or obscure meaning being

transferred. If the message is to be communicated correctly, MEANING MUST HAVE PRIORITY

OVER FORM.

6

2.4.2 FORM IS IMPORTANT TOO

This does not mean that form is unimportant. Within each language, it is the form which indicates the

meaning. It is, therefore, of the utmost importance to study the form of both the source language message

and the receptor language with the greatest attention to detail.

The smallest differences of form may signal important shades of meaning. If the translation is to be

accurate and faithful, the translator must be aware of these distinctions and must seek to re-express those

shades of meaning exactly in the translation, using the appropriate forms to do this in the receptor

language.

For this reason, the exegesis step of translation is extremely important. A major part of the work of the

Bible translator is careful research into the exact meaning of the source message. It is strongly desirable

that the translator should have a good knowledge of Biblical languages so that he can refer back to the

original form of the message.

2.4.3 QUALITIES OF A GOOD TRANSLATION

The three most important qualities of a good translation are:

1. ACCURACY -- correct exegesis of the source message, and transfer of the

meaning of that message as exactly as possible in the receptor language.

2. CLARITY -- there may be several different ways of expressing an idea—choose the way

which communicates most clearly; the way which ordinary people will understand.

3. NATURALNESS -- it is important to use the natural form of the receptor language, if the translation

is to be effective and acceptable. A translation should not sound foreign.

The translator is constantly struggling to achieve the ideal in all these three areas—no easy task. When it

seems impossible to reconcile all three, then ACCURACY must have priority.

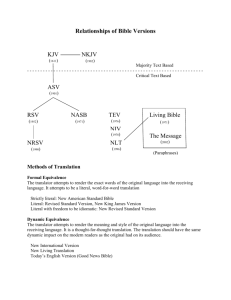

2.6 KINDS OF TRANSLATION

A “word-for-word” translation, which follows closely the FORM of the source message, is called a

LITERAL translation. Examples of completely literal translations would be the interlinear translations of

Mark 2:19–20 and of Genesis 49:10 given in section 2.5 above..

A MODIFIED LITERAL translation follows the form of the source message as closely as possible,

generally making only those adjustments which are necessary to avoid forms which would be

ungrammatical in the receptor language. This kind of translation is illustrated by the King James Version

and the Revised Standard Version in the examples in section 2.5. Notice that a modified literal translation

usually:

- follows the word order of the source text as closely as possible

- keeps the same parts of speech wherever possible, translating a noun by a noun, and a verb by a verb

- translates idioms in the source text word-for-word (e.g., KJV, children of the bridechamber in Mark

2:19)

- retains discourse features, such as sentence connections or use of pronouns, exactly as in the source

text.

By contrast, a translation which aims to express the MEANING of the source text in the natural form of

the receptor language is referred to by Beekman and Callow as an IDIOMATIC translation. An

idiomatic translation gives priority to the communication of the meaning of the source text.

Nida and Taber use the term DYNAMIC to describe a translation which focuses on meaning. They

emphasize that a translation should not only communicate exactly the information given in the original

message, but should also arouse the same emotional response in the hearers. The Good News Bible is an

example of an idiomatic or dynamic translation.

Thus there is a continuum ranging from extreme literal translation, through modified literal to idiomatic

or dynamic translation. The various English versions could be placed along this continuum at different

7

points. The criterion is how closely does the version follow the form of the original text. A modified

literal translation reproduces the grammatical or lexical form of the source text as closely as possible. The

priority of an idiomatic translation is to communicate the message of the source text as clearly and

naturally as possible; in order to achieve this purpose it is sometimes necessary to use a different

grammatical or lexical form in the receptor language.

There is another continuum along which versions could be measured. This is the scale of accuracy—how

accurately does the translation express the meaning of the source text?

These two dimensions can be charted as follows:.

CLOSENESS TO THE FORM OF THE SOURCE TEXT

LITERAL

MODIFIED

LITERAL

IDIOMATIC/

DYNAMIC

MAXIMUM

ACCURACY

CLOSENESS

TO THE

MEANING

OF THE

SOURCE TEXT

MIMIMUM

ACCURACY

DISCUSSION Consider the various versions of the Bible with which you are familiar.

Where on the above chart do you feel that each version would fit?

When contemplating translation into a new language, it is necessary to consider several questions before

deciding what kind of a translation should be made:

For whom is the translation intended? Is it for “ordinary,” less educated people, or is it for the

educated élite?

For what purpose will the translation be used?

Are there already well-trained preachers and teachers in the area who will be able to explain

the Scriptures?

EXERCISES FOR CHAPTER 2

(1) From your own experience of learning a foreign language, or from observation, give two examples of

instances where different forms are used in different languages to express equivalent meaning.

e.g., German:

Er macht den Kurs..

lit.,

He makes the course.

English:

He is taking the course.

Korean:

He is stepping the course. (편집자 추가)

(5) Below is the Greek text of Mark 2:5 with a literal, word-for-word translation in English. In any

language of your choice, give both a modified literal and an idiomatic translation of this text. You may

refer to any versions of the Bible, but please make your own translation; do not just quote another

version.

If you make your translation into a language other than English, then please also provide a word-forword back translation in English.

8

When you have completed the translation, write a brief note identifying three specific points where your

idiomatic translation is more natural or clearer than your modified literal translation.

Mark 2.5

[막 2:5]

having seen the Jesusthe

faith

of-them, he-says

to-the paralyti,

“Child,

are-forgiven

of-you the sins.”

9

CHAPTER 3: MEANING IN CONTEXT AND ‘CONCORDANCE’

Chapters 3 to 9 cover the second module of this course. The focus of this part of the course is LEXICAL

MEANING, mainly the meanings of words.

In this study we shall be concerned primarily with vocabulary-words; that is, words which have some

kind

of referential meaning, which refer to things or events or attributes. Words of this kind are sometimes

called CONTENT words; they should be distinguished from relational words, e.g., prepositions, definite

and indefinite articles or conjunctions, whose function is to signal relationships.

3.1 ONE WORD—MANY SENSES

In any language, there are many words which have a number of different senses.

e.g., English “dressed”

1. He dressed himself quickly as it was cold.

2. The nurse dressed the wound as best she could.

3. He dressed the window in preparation for the January sales.

4. She dressed the chicken in readiness for the meal.

5. She dressed her favourite doll in a pink kimono.

6. The soldiers dressed ranks at the officer’s command.

7. She dressed the salad as usual.

8. They dressed the ship with flags in honor of the President’s visit.

Example from John Callow

3.2 THE CONTEXT OF A WORD INDICATES WHICH SENSE APPLIES

For any particular occurrence of a word, how can one know which sense of that word is intended? It

is the CONTEXT which provides the clue.

Sometimes the clue is in the grammatical context.

In sorting out the different senses of a word, the first step is usually to sort out the different grammatical

usages, and to study these separately. This does not mean that there is no meaning relationship between,

for example, the same word when it is used as a noun and as a verb, but the grammatical differentiation

provides a useful starting point for analysis.

eg.,

I don’t believe the world is round.

The book shop is round the corner.

He fired his last round.

Let’s sing a round.

Round off the figures to the nearest pound.

Adjective

Preposition

Noun

Noun

Verb

3.3 PRIMARY AND SECONDARY SENSES

The PRIMARY sense of a word is usually the sense in which that word is most commonly used

in the language. It is the sense which native speakers of the language will think of when they

hear the word in isolation. It is therefore the sense which is least dependent on the context.

It is the primary sense which usually occurs as the first entry for a word in a dictionary.

The other senses are often referred to as SECONDARY senses. Secondary senses may be

considered to be derived from the primary sense.

e.g., The primary sense of ‘fork’ in English refers to a pronged instrument which is used for eating (or

digging). A ‘fork in the road’ would be a secondary sense.

‘Cook’ in English generally refers to the preparation of food. This is the primary

sense. But in certain limited contexts, ‘cook’ can have the secondary sense of adjusting

accounts, usually with some evil intention; e.g., ‘he cooked the books’.

10

3.4 CROSS-LANGUAGE MIS-MATCH

The senses which a word has in one language often do not match all the senses of the

equivalent word in another language. Even when the “primary” senses seem to match,

different words may be used to express the secondary senses.

e.g.,

(a) French ‘marcher’

1. Le bébé ne marche pas encore.

2. Le train est en marche.

3. Les affaires marchent.

4. Est-ce que ça marche?

5. La montre marche.

6. Je ne marche pas dans

cette affaire.

English ‘walk’

‘The baby isn’t walking yet

‘The train is moving’

‘Business is going well’

‘Is that working out?’

‘The watch is working’

‘I have nothing to do with

this matter’

3.5 REFERENCE

One aspect of the meaning of a word is its reference. Each sense of a content word refers to some thing,

or event, or attribute. The reference may be either to the class of things, or events, or attributes, which, in

that language, are included under that word (i.e., are potential

referents of that word), or it may be to a specific example of that item.

e.g.,

English

Mbembe (Nigeria)

red

orange

yellow

okora

green

blue

black

obina

English

Mbembe

animal

fish

corresponds

to

eten

meat

I saw an animal in the bush

He’s eating meat.

He caught a fish in the river

-

Nze eten z'egba.

Ochi eten.

Owa eten z'oraanga.

3.8 IMPLICATIONS FOR TRANSLATION

In translation into another language, the word which gives the correct sense in each

separate context should be used. This means that it will not always be possible to translate the same

word in the source language by the same word in the receptor language.

e.g.,

‘spirit’ (The English word spirit roughly corresponds to the N.T. Greek word pneuma)

Matthew 8:16 He cast out the spirits with a word

11

Mark 3:30 He has an unclean spirit.

Acts 23:9 Maybe a spirit or an angel has spoken to him.

Acts 2:4 They speake as the Spirit gave them utterance.

Mark 1:12 The Spirit immediately drove him out into the wilderness.

Matthew 26:41 The Spirit indeed is willing, but the flesh is weak.

Colossians 2:5 Though I am absent in body, yet I am with you in spirit.

Luke 24:37 They were startled and frightened and

supposed that they saw a spirit.

Philippians 1:27 You stand firm in one spirit, with one mind.

Notice that the Greek word pneuma has yet another sense: ‘wind’ as in John 3:8 “The wind blows where

it will.” Nearly all English translations use the word ‘wind’, not ‘spirit’, in order to translate this verse

meaningfully.

Example 2 Study the translation of the Greek word stoma in the following passages. The primary

sense of stoma of ‘mouth’.

Matthew 15:11 Greek: [마 15:11]

not the entering-thing

RSV

NIV

into

the mouth

does not (the)

man

not what goes into the mouth defiles a man

what goes into man’s mouth does not make him unclean.

Matthew 18:16 Greek: [마 18:16]

by

mouth (of)

RSV

GNB

two

witnesses

or three

by the evidence of two or three witnesses

by the testimony of two or more witnesses

Luke 21:15 Greek: [눅 21:15]

I

for

will-give you

KJV

NIV

JBP

mouth

and

wisdom

I will give you a mouth and wisdom

I will give you words and wisdom

I will give you such eloquence and wisdom

Hebrews 11:34 Greek: [히 11:34]

they-escaped mouths

KJV

NEB

of-sword

(they) escaped the edge of the sword

(they) escaped death by the sword

2 John verse 12 Greek: [요2 1:12]

to-come

to

you

and

mouth

to

mouth

12

to-speak

KJV

RSV

GNB

JBP

to come unto you, and speak face to face

to come to see you and talk with you face to face

to visit you and talk with you personally

to come and see you personally, and we will have a heart-to-heart talk together

13

CHAPTER 5: COMPONENTS OF MEANING

5.2 PRINCIPLES OF CONTRAST

Summary: It has been illustrated above that, in order for there to be definable contrast, there must

also be some grounds of comparison. There must be some feature(s) which the items compared share.

It is not very productive to compare, for example, the meaning of ‘mongoose’ with ‘sea’; it is more

illuminating to compare ‘mongoose’ with ‘rat’, ‘dog’, ‘racoon’, etc., with which it shares some

features of meaning.

So, for the purpose of this kind of contrastive study, words need to be grouped into ‘sets’, each set

having one or more shared features of meaning..

For example, the set of words man, woman, boy, girl, has the shared feature of meaning ‘human’. The

words themselves contrast with each other in respect of the features ‘adult’ in contrast to ‘young’, and

‘male’ in contrast to ‘female’. This can be diagrammed:

‘adult’

‘young’

‘male’

‘female’

man

boy

woman

girl

and may be alternatively represented:

man:

+human

boy:

+human

woman: +human

girl:

+human

+adult

-adult

+adult

-adult

+male

+male

-male

-male

or:

man

+

+

+

‘human’

‘male’

‘adult’

boy

+

+

-

woman

+

+

girl

+

-

or:

man

human

male

adult

boy

human

male

young

woman

human

female

adult

girl

human

female

young

5.3 COMPONENTIAL ANALYSIS

Each word is thus viewed as a bundle of features of meaning called ‘components’ and the purpose of

this kind of analysis is to break down the meaning of a word into its underlying components. This

approach is therefore often referred to as componential analysis.

In comparing a set of words, there will be:

a. shared components (sometimes termed ‘generic components’), i.e., features of meaning which all the

words in the set have in common with each other.

e.g.,

for the set man, woman, boy, girl, a shared component of meaning is ‘human’.

14

The same features of meaning may become contrastive if the words are then compared with words

outside the set; e.g., if man is compared with stallion, ‘human’ then becomes a contrastive feature, in

opposition to ‘animal’.

b. contrastive components (sometimes referred to as ‘diagnostic’ or ‘specifying’ components), i.e., those

meaning components by which the meaning of a given word is distinguished from the meaning of other

words in the same set.

c. supplementary components (also termed ‘incidental components’)

There are two kinds of supplementary components:

One type of supplementary components are those meaning associations which are attached to the word

itself, rather than to the thing referred to by the word.

e.g,.

the words ‘policeman’ and ‘cop’ have the same referent,

i.e.,

they both refer to the same thing. But they reflect different attitudes on the part of the speaker,

and would be appropriate in different styles of speech.

See further the discussion of ‘associative meaning’ in Chapter 7.

Another type of supplementary components are those components which may be crucial and contrastive

in certain usages of the word, but not in all. Nida (1975a page 35) gives the example of ‘father’ in such

contexts as:

‘he was like a father to the boy’

where the associated qualities of ‘father’ as ‘one who takes care of his children’, ‘one who is a constant

companion’, become more central to the meaning that the usual contrastive components of the word, e.g.,

male sex, biological progenitor.

There will also be many other aspects of meaning which are associated with a given word, but which are

not necessarily part of its definition. These include all the typical facts about the referent which would

make up an encyclopaedic description, including every aspect of the function of that item within the

particular culture.

5:6 APPLICATION TO BIBLICAL KEY WORDS

The same technique for studying the meaning of a word can be applied to special terminology, such as

Biblical key words. A comparative study of words in a certain area of meaning in the source language can

help the translator to discover the precise meaning of each word and to recognize the significant

differences of meaning. Similarly, a comparative study of available words in a certain area of meaning in

the receptor language may help the translator to discover which term is closest in meaning to the concept

he wishes to translate.

e.g., Consider the words in the set which has the shared component of meaning ‘kinds of shelter used for

religious purposes’. In English, this set includes:

tabernacle, Temple, synagogue, church*

Shared component of meaning “kinds of shelter for religious purposes”

Contrastive components of meaning:

(a)

tabernacle

Temple

synagogue

church

place where

God is present

place where

God is pre-

place where

people meet

place where

people meet

15

and meets with

his people

sent and

meets with

his people

usually for

religious

activity

for religious

activity

(b)

temporary

movable

shelter

permanent

building

permanent

building

permanent

building

(c)

only one

only one

(in

Jerusalem)

many in

different

places

many in

different

places

(d)

used by

Jews

used by

Jews

used by

Jews

used by

Christians

(e)

people went

to make

sacrifices

people went

primarily

to make

sacrifices

people went

for reading

of the law,

teaching,

prayer (not sacrifices)

people go

for worship,

prayer

teaching (not

sacrifices)

EXERCISES FOR CHAPTER 5

(1) In any language of your choice, apply steps 5 and 6 for the set of words which has the shared

component ‘object for sitting on’. Limit the number of words in the same class to not more than six.

e.g., English: chair, sofa, stool, bench, pouffe, throne

(2) In any language of your choice, apply steps 5 and 6 for the set of words which has the shared

component ‘kinds of footwear’

e.g., English: boot, shoe, slipper, sandal, galoshes, clog

16

CHAPTER 6: OTHER LEXICAL RELATIONSHIPS

Part of the meaning of a word is its relationship to other words in the language. We have already

considered one such relationship between words, that of belonging to the same set through having some

shared component(s) of meaning. But there are also many other relationships which words may have to

each other within the lexical system of the language.

6.1 HIERARCHICAL RELATIONSHIPS

Sometimes the relationship between two words is such that all the meaning of one of the words is

included within the meaning of the other.

For example, if you compare the two words furniture and chair it will be recognized that the two have

some shared components of meaning. But if you try to draw up a list of the contrastive components, it

becomes clear that there is in fact no contrast between them; everything which is true of ‘furniture’ is also

true of ‘chair’. ‘Chair’, therefore, may be defined as a specific ‘kind of’ furniture.

This relationship is referred to as ‘hierarchical’ relationship. Palmer (1974) calls it ‘inclusion’, and Lyons

(1977) terms it ‘hyponymy’ (from the Greek hupo “under”). The more general term is described as

GENERIC, while the less general term is described as SPECIFIC.

Examples

generic

meat

garment

colour

to sew

to speak

specific

beef, mutton, veal, pork

dress, shirt, vest, coat

red, yellow, green, blue

to hem, to seam, to embroider, to tack

to shout, to whisper, to stutter

Note that the same word may be specific in relation to one word, and generic in relation to another set of

words:

furniture

chair, table, cupboard, bed

chair

arm-chair deck-chair, high-chair, recliner

furniture

‘things for sitting on’

‘things for sleeping on’

sofa

arm-chair

stool

bench

deck-chair

pouffe

specific

generic

chair

throne

high-chair

recliner

CRITERIA FOR CLASSSIFICATION

Notice that each language has its own hierarchical classification. In one language there may be ‘generic’

words for which there is no equivalent in another language.

e.g. Izi (Nigeria): nri approximately equivalent to English 'food', includes all staple foods,

such as yam and cassava, but excludes meant, drink and vegetables.

Mbembe (Nigeria): ewakpo literally “soup things,” includes everything which could

form ingredients for stew, including pepper, bush-mango, tomatoes, green-leaf. It therefore overlaps

with the meaning of the English word 'vegetable' but is by no means identical in its coverage.

17

CHAPTER 9: TRANSFERRING LEXICAL MEANING FROM ONE LANGUAGE TO

ANOTHER

9.1 WHERE THE CONCEPT IS KNOWN IN THE RECEPTOR LANGUAGE CULTURE

Even though the concept which the translator wishes to express is known in the receptor language

culture, this does not mean that it will necessarily be expressed in the same form as in the source

language.

Here are a few examples of some of the changes of form which may occur. All the examples given below

illustrate changes of form which have been necessary in specific languages when there is no form which

corresponds exactly to the form in the source language.

a)

SL

single word

e.g., parents

the heathen

to receive you

he is faithful

bring

fetch

village

kill

grace

RL

----------

phrase in which the meaning

components are separated out

father and mother

people who do not know God

to agree that you stay at his home (Mark6:11)

he will do what he has said (Hebrews 10:23)

take come

go take come

small town

cause to die

loving mercy

It is important to check the meaning of the word in the particular context in which it is being translated:

e.g.,

Acts 8:27

the queen of the Ethiopians --- the woman who ruled the people of Ethiopia

Esther 2:22

Queen Esther

-- Esther, the wife of the king

Mark 14:31

I will not deny you

-- I will not say that I do not know you

Sometimes it may be necessary to use a speech quotation form:

e.g.,

Hebrews 11:21

he blessed them

-- He said, “May God do good to you.”

Mark 14:70

he denied it

b)

SL phrase

(non-Biblical example)

dung of sheep, goats and deer

Hebrews 9:12

the blood of goats and bulls

c)

-- He said, “I am not the one.”

RL

single word

Mundani (Cameroun): asaa

Duka (Nigeria): tgt includes domestic

animals, such animals as would be sacrificed

both in Biblical culture and in Duka culture,

as opposed to nem which includes all wild animals.

SL two or more

synonyms having

the same referent

e.g., N.T. Greek/English

RL

18

only one form available

kakos/poneros

bad /evil

hamartia/adikia/anonima/paraptoma

sin/unrighteousness/lawlessness/trespass

d)

e)

SL

two antonymns available

e.g.,

good and bad

slave and free

Jew and Gentile

-- many languages have only one

word to cover this area of meaning

-- similarly, in some languages it may be

necessary to translate all these words

by the same form (depending, of course,

on the context)

----

RL

only one form available,

plus negative

good and not good

slave and not slave

Jew and non-Jew

SL

RL

only reciprocal available

Sometimes a form can most readily be translated using a reciprocal form in the RL:

e.g., 1 Corinthians 11:23

I received from the Lord what I also delivered to you.

If there is no expression for ‘received’ in the RL, this might be rendered:

It was the Lord (himself) who taught/revealed to me that which I have now delivered to

you

Acts 16:9

A vision appeared to Paul in the night.

--- Paul saw a vision/revelation in the night

f) Transfers involving idiomatic forms or figures of speech

i.

ii.

SL

e.g.,

SL

e.g.,

idiomatic or figurative

Acts 7:51

stiff-necked

RL

direct, non-figurative form

--

stubborn

Isaiah 13:18

they will have no mercy

on the fruit of the womb

--

they will have no mercy

on children

Genesis 31:20

lit. Hebrew: he stole his

heart

--

he outwitted him

direct form

be sad

--

he married

hypocrite

---

Mark 5:43

he strictly charged them

--

Mbembe (Nigeria): lit., he pulled

their ears

Acts 18:6

I am not responsible

--

Igede (Nigeria): lit., my hand and

foot are not there

Luke 22:56

19

RL

idiomatic, figurative form

Hausa (West Africa): lit., have

a black heart

Kasem (Ghana): lit., he ate a woman

a man with two hearts

a man with two tongues

she looked straight at

him (GNB)

iii.

SL

e.g.

--

idiomatic, figurative

form

hardness of heart

--

Igede: lit. she bit him with

her eye

RL idiomatic, figurative

but with a different figure

Mbembe (and many West African

languages): lit., hardness of head

g) Transfer involving generic/specific mismatch

As we have seen, words in different languages have different areas of reference. It may sometimes

happen that there is no word in the receptor language at the same level of generality as a certain

source language word. Therefore it is sometimes necessary to use a word in the receptor language

which is either more generic or more specific in the source language.

The basic principle is always to use a word which gives the correct sense, equivalent to the sense

of the original word, in each particular context..

i.

SL

e.g.,

specific

Luke 11:3

Give us each day our

daily bread

RL

Acts 3:6

Silver and gold have

none

ii.

SL

e.g.,

generic

English ‘swim’

more generic

--

Many languages translate this

verse as …. our daily food

--

It may sometimes be appropriate

to translate this verse as: I have no money

RL

more specific

Tlingit (Alaska) has no general word

for ‘swim’ but instead has many more

specific words, depending on the kind of

swimming involved, the participants

involved, and their singularity or

plurality:

di-taach (sing.)

ka-doo-ya-taach (pl.)

ya-x'aak (sing.)

ka-doo-ya-x'aak (pl.)

(of human body)

(of large fish or sea mammal

swimming under water)

ya-heen

(of shoal of fish swimming under

water)

ya-hoo (sing.)

ya-kwaan (pl.)

(of animal or human swimming

on the surface

ji-di-hoo (sing.)

ji-dzi-kwaan (pl.)

(of animal or human swimming

on the surface aimlessly, in

circles)

si-hoo (sing.)

si-kwaan (pl.)

(of bird on the surface)

ya-dzi-aa (sing.)

ya-si-xoon (pl.)

(of bird or fish swimming under

water with head emerging)

20

dli-tsees (sing.)

ka-doo-ya-tsees (pl.)

of something swimming fast and

powerfully, especially sea

mammal)

ya-ya-goo (sing.)

ya-si-goo (pl.)

(of porpoises swimming as a

school)

data from Con Naish

Further e.g., English ‘carry’

jelup'in

nol

chup

chuy

lats

pach

toy

yom

lut'

pet

cats'

lup

lat'

cuch

Tzeltal (Mexico) has no general word

for carry, but many more specific terms:

‘to carry across the shoulders’

‘to carry in the palm of the hand’

‘to carry in a pocket or pouch’

‘to carry in a bag’

‘to carry under the arm’

‘to carry on the head’

‘to carry aloft’

‘to carry different items together’

‘to carry with tongs’

‘to carry in the arms’

‘to carry between one’s teeth’

‘to carry on a spoon’

‘to carry in a container’

‘to carry on the back’ etc.

9.2 WHERE THE CONCEPT TO BE TRANSLATED IS NOT KNOWN IN THE RECEPTOR

LANGUAGE CULTURE

When the concept to be translated refers to something which is not known in the receptor language

culture, then the translator’s task is much harder. In this case it is not just a matter of finding the

appropriate way to refer to something which is already part of the experience of the hearer; instead, a

completely new concept has to be communicated.

In addition to careful verbal translation in the text itself, there are other aids which can be used to achieve

effective communication. These include:

a)

pictures—well-chosen, well-placed, historically accurate pictures can be a real help to the

reader.Pictures are not just ‘decoration’ but can help the reader to understand something which is

referred to in the text.

One edition of the Bible which deliberately uses illustrations to aid the understanding of the

reader in this way is the RSV edition published by Collins for the British and Foreign Bible

Society with illustrations by Horace Knowles. The Introduction to this edition explains:

“Instead of the usual type of story-picture, there are simple little drawings that look more like

up-to-date visual aids than illustrations.… they have been fitted into the text just at the place

where help is needed.” These illustrations include pictures of

- animals and plants referred to in the text which may be unfamiliar to the reader, e.g.,

camel, bear, nard, hyssop, fig tree, vine with grapes, etc.

- aspects of biblical culture which may be unfamiliar, e.g. shepherd with sheep, ploughing

using oxen, a watch-tower in a vineyard, sower sowing seed by casting, etc.

- aspects of the Jewish religious system which may be unfamiliar, e.g. the tabernacle,

priests and Levites in their official regalia, altars, seven-branched candlestick, phylactery;

21

synagogue, Temple, etc.

Pictures used for this purpose must be

i. clear and easy to understand (test them out with the receptor audience)

ii. accurate and true to the biblical culture.

b)

glossary—Some editions of the Bible, such as the Good News Bible, give a glossary at the back

of the book, with an expanded explanation of unknown concepts.

Such a glossary can be useful for explaining such terms as ‘Pharisee’, ‘Sadduccee’, ‘Son of

Man’, and many others. In an edition of the New Testament only, it can also be used to provide

brief background information about the main Old Testament characters who are mentioned in the

New Testament.

But it should be remembered that many readers will not refer to the glossary at the time when

they are reading the text.

c)

footnotes—Footnotes can be useful to provide more background detail or explanation than can

acceptable be included in the text itself. They can also be useful at certain points where, in order

to achieve a meaningful translation, it has been necessary to change the form of the text. The

literal form of the source text can then be given in the footnote, with an explanation, if

appropriate.

But footnotes should be used very sparingly (unless the edition is intended as a study edition).

Too many footnotes distract the attention of the reader from the text and can be confusing rather

than helpful.

Care should be taken, too, to ensure that the footnotes are clearly distinguished from the text, e.g.

by using a different, smaller, typeface and/or by having a line under the text. above the

footnotes. Otherwise there is a danger that readers, especially newly literate readers, will read the

footnotes as if they are part of the text.

d)

introduction—Some editions include a brief introduction to each book. Such introductions

should be limited to factual information ~ avoid interpretation or comment.

Sometimes there is certain factual information which the reader needs to know in order to

understand the message of the book. For example, an understanding of the message of Galatians

depends on an understanding of the function of circumcision in the Jewish culture. A brief

explanation of the function of circumcision in Jewish culture could therefore be profitably

included in an introduction to the book.

e)

Bible background booklet—More detailed information about the way of life in Biblical times

can be given in a separate booklet. For example, see the booklet How the Jews lived, which was

prepared by the Papua New Guinea branch of Wycliffe Bible Translators. Such a booklet needs

to be carefully adapted for the needs of each receptor culture, bearing in mind the particular

points of difference between that culture and the Biblical culture.

ALL OF THE ABOVE SUPPLEMENTARY AIDS CAN BE HELPFUL IN ACHIEVING

COMMUNICATION OF AN UNFAMILIAR CONCEPT. BUT NONE OF THEM IS A SUBSTITUTE

FOR MEANINGFUL TRANSLATION IN THE TEXT ITSELF.

There are three basic possible alternative ways of translating unknown concepts. These are:

1) Use a descriptive phrase.

2) Use a foreign word

3) Substitute a concept which is known in the receptor culture.

Each of these three ways has its advantages, and also its dangers and problems. The translator has to

decide which way, or which combination of these ways, is most appropriate in each particular context.

22

In deciding which way of translating a new concept is most appropriate in each context, two aspects of the

meaning of that concept need to be considered. One is the SURFACE FORM OR APPEARANCE, the

other is its FUNCTION OR SIGNIFICANCE WITHIN THE CONTEXT AND WITHIN THE CULTURE. It

may well be impossible to communicate all aspects of the form and function of the new concept ~ the

translator needs to focus on what is most relevant in the context, on what the receiver of the translated

message needs to know in order to understand the total message. See the examples below.

The three ways of translating will now be discussed in turn:

1) USE A DESCRIPTIVE PHRASE

The descriptive phrase usually involves a generic term, plus a description which focuses on

that aspect of the surface form, or of the function, of the concept which is most relevant in

the context.

e.g.,

Matthew 21:33

winepress—hole in the rock (surface form, appearance) where they squeeze the fruit

juice (function)”

Acts 27:13

they weighed anchor—“they lifted the heavy iron weight (surface form, appearance)

which they used to keep the boat still (function)”

Matthew 5:23

altar—“a place/platform/table (surface form, appearance) where people make

sacrifices to God (function)”

Matthew 13:33

leaven—thing which makes the bread swell (function)”

angel—messenger of God (function)”

John 10:12

wolf—a fierce wild animal (function)”

Revelation 17:4

jewels and pearls—different kinds of beautiful rocks/stones (surface form, appearance)

which one uses to adorn things (function)

2) USE A FOREIGN WORD

Note The terms foreign word and loan word are sometimes confused.

A loan word is one which has been borrowed from another language and adopted into the

new language. It has become part of that new language, often being modified in its

phonological form to the natural pattern of that language. It is known to all speakers of

the language, including those who speak no other language than their mother tongue.

Loan words may be used freely in the translation since they communicate

meaning. They have become part of the language. However you may sometimes find that

some speakers of the language want to avoid using loan words in order to keep the

language ‘pure’. This question has to be decided by the local translation committee or

other leaders. Apart from adverse reaction of this kind, which may lead to rejection of the

word, there is no theoretical reason why loan words cannot be used freely.

A foreign word, on the other hand, is one which is not known to the speakers of the receptor

language. It therefore does not in itself communicate any meaning to them, (except to those

people who also speak the language from which the word is borrowed). Foreign words carry

zero meaning for most people and should therefore be avoided when possible.

23

Where foreign words are used, the context should be ‘built up’ to communicate as much meaning

as possible. For example, when it is necessary to use a foreign word in order to refer to a specific

variety of animal, plant etc., which is not known in the receptor culture, then the foreign word can

be introduced by the use of a generic term which will give the reader some idea of the meaning of

the foreign word.

e.g.,

camel — “animal called camel”

grape — fruit called grape”

Passover — “festival called Passover”

Focus on that aspect of the meaning of the concept which is relevant in each particular context. this may

be different in different contexts:

e.g.,

myrrh

—

—

Matthew 2:11 “precious oil called myrrh”

Mark 15:23 “medicine called myrrh”

There are other ways, too, in which the context can be carefully phrased in order to communicate as much

as possible of the full meaning. In translating proper names, for example, or other very specific words,

where the translator wishes to retain the name and also to communicate clearly its exact meaning or

reference:

e.g.,

Satan

—

Revelation 1:8

a pha and omega —

Mark 8:29

You are the Christ. —

“Satan, chief of the evil spirits”

The first and the last, alpha and omega”

(In a later reference, Revelation 21:6, both the names and their

meaning are explicitly included in the original Greek text.)

You are (the) Christ, he whom God has chosen/appointed.” (Notice

that in this context the meaning of the title ‘Christ’ is crucial for the

understanding of the statement.)

Remember that the main danger of using a foreign word to translate an unknown concept is that of noncommunication. So every passage in which a foreign word is used should be very carefully tested to find

out whether the meaning of the source message is in fact effectively communicated to the speakers of the

receptor language.

3)

SUBSTITUTE A CONCEPT WHICH IS KNOWN IN THE RECEPTOR CULTURE

which has the same function as the concept in the source culture.

The source message comes from the background of a particular historic culture, and describes events

which happened in a specific historic setting. Clearly it would be wrong to translate in a way which would

‘change’ the historical facts or which would make it appear as if the events happened in the receptor

language culture.

There are, however some contexts in which the focus is the illustration of a teaching point, and in which

there is no reference to something which actually happened historically. In such contexts it is the

communication of the teaching point which seems to be more important than the surface form of what is

referred to. It is in such contexts that the translator may decide to use a ‘cultural substitute’, i.e. something

which has the same function in the receptor language culture as the concept referred to in the source text

had in the original Biblical culture.

e.g.,

Luke 9:58

foxes have holes —“bush rats have holes”

(The main point here is reference to an animal which is known to have its own

hole, not the exact species of the animal.)

24

Mark 9:42

it would be better for him if a great millstone were hung round his neck … grinding

stone…. (The main point here is the size and weight of the stone—the difference

in the way in which grinding is done in the Biblical culture and the receptor

culture is not in focus.)

James 3:12

Can a fig tree yield olives, or a grape vine figs?

—If the exact botanical species of ‘fig’, ‘olive’ and ‘grape’ are not known in the

receptor culture, it may be possible to substitute here species which are known,

since the main point is that a tree of one kind cannot bear fruit of another kind.

Revelation 1:14

—white as snow…“white as egret’s feathers”

“white as cotton”

(substituting something which is known for its whiteness in the receptor

culture)

In considering the use of a cultural substitute, note the following principles:

a) Do not ‘change’ historical facts. Where an actual historical event is referred to, the translation must

be historically accurate: e.g., Mark 11:13 It would not be possible to substitute, for example,

‘orange tree’ for ‘fig tree’ in this context since it was not, historically, an orange three that Jesus

cursed.

b) The cultural substitute should not be something which is incompatible with Biblical culture.

Sensitivity is needed in selecting substitutes which are appropriate and acceptable.

c) In choosing substitutes for specific species, e.g., of animal or plant, always choose a substitute

which is as similar as possible to the original referent, bearing in mind both the outward

appearance and the function within the context and culture. e.g., Luke 13:32 ‘go and tell that fox’—

an animal such as ‘hyena’ might be substituted for fox, provided it had the appropriate meaning

associations in the receptor culture, since foxes and hyenas are fairly similar species, but one

might feel uneasy about substituting a totally different species such as ‘spider’.

d) There are certain themes which run through the bible, such as references to the shepherd and his

sheep, to vineyards, to leaven; in those contexts in which there may be some significant meaning

link, be careful to retain consistency in the translation.

SUMMARY OF 9.2 We have seen that there are three possible ways of translating unknown

concepts:

1. Use a descriptive phrase

2. Use a foreign word

3. Substitute a concept which is known in the receptor culture.

Each of these has its advantages and disadvantages. Care needs to be taken to discern which is

appropriate for each particular passage. Sometimes the ways may be combined, e.g. a foreign word

together with a descriptive phrase which gives some idea of the meaning. In all cases it is necessary to

keep in mind both the surface form or appearance of the unknown concept, and also its function within

the biblical culture, to discern which aspects of its meaning are essential for the understanding of the

total passage and to make sure that these are communicated in the translation.

9.3 A NOTE OF WARNING

25

There may be some concepts in the source message which appear on the surface to be similar to concepts

which are known in the receptor culture, but which, on closer examination, prove to be very different in

their function or significance.

The receivers of the translated message will interpret the message in the light of their own culture.

Special care is needed, therefore, to ensure that the function of the concept within the original culture

is communicated, wherever this is necessary for the correct understanding of the message.

e.g., Colossians 4:11

These are the only men of the circumcision among my fellow workers. RSV

Circumcision is known in many cultures. But its function within each culture may be very

different. In some cultures (e.g., U.S.A..) it has no religious significance but is done

purely for medical and hygienic reasons. In some cultures it is done to teenage boys and

is associated with attaining manhood, in others it may be associated with joining a

particular cult, or being recognized as part of a certain family group. But the correct

understanding of Biblical references depends on the fact that, in Biblical culture,

circumcision signified becoming a Jew. For this reason, the Good News Bible translates

Colossians 4:11: ‘These three are the only Jewish converts who work with me …’

Matthew 21:8

Others cut branches from the trees and spread them on the road.

In one African culture, cutting branches and spreading them on the road was a familiar

concept, but it was associated with action taken to block the road to prevent an unwanted

person or enemy from approaching. In this language the misunderstanding was avoided

by using the more specific word meaning ‘palm branches’. (This information is explicit

in the parallel passage in John 12:13.)

Luke 18:13

the tax collector … beat his breast

In one culture, beating the breast was understood to be an act of defiance. To translate

only the surface form would therefore have resulted in misunderstanding. In this

particular language the solution was to translate using a slightly different surface form,

literally ‘to hug the breast’ which in that culture had the appropriate implication of

humility and repentance.

1 Thessalonians 5:26

Greet all the brethren with a holy kiss.

In Biblical culture, the kiss was the normal form of greeting between friends. In some

cultures, a kiss could only refer to an action between a mother and her child, or to love

making (the latter association being sometimes recently developed from watching

European or American films). For this reason, perhaps, J.B. Phillips translates 1

Thessalonians 5:26:

‘Give a handshake all round among the brotherhood’ --- translation with which one can

sympathise even while questioning its appropriateness since it ‘changes’ the cultural

background.

EXERCISES FOR CHAPTER 9

(1) Imagine that you are translating into a language which has no one-word lexical equivalent for the

words underlined below. Re-express the meaning of each underlined word as a phrase. Check the Biblical

context where necessary.

a) 2 Timothy 1:5 grandmother.

b) Luke 1:27 virgin

c) John 10:36 you are blaspheming (Note the context.)

d) Acts 3:15 To this we are witnesses.

e) Acts 10:12 in it were all kinds of animals and reptiles

f) Acts 16:39 They apologised

26

g) 1 Corinthians 12:18 God arranged the organs in the body

h) 2 Corinthians 4:11 our mortal flesh

i) 2 Corinthians 4:17 this small and temporary trouble (GNB)

j) Hebrews 2:11 he who sanctifies (Note the context.)

k) Hebrews 6:14 “Surely I will bless you and multiply you.”

l) Hebrews 11:9 he sojourned in the land of promise

(5) This exercise may be done in small groups of two, three or four persons. Each group should

include a native speaker of a language other than English, preferably a non-European language.

Translate Acts 8:26—28 into that language, paying particular attention to the translation of the

following words:

Angel south desert eunuch queen treasure chariot prophet

(7) One problem area is how to translate terms for weights and measurements, and also for amounts of

money, when the system used in the receptor culture is different from the system in the source

culture.

Should the translator,

i. retain the ‘foreign’ terms, possibly adding explanatory footnote?

ii. re-express the amounts and units of measurement using the system which is in current use

in the receptor culture?

iii. use some other method?

Discuss these questions with reference to the various English translations of the passages quoted

below. Comment on the advantages and disadvantages of each rendering:

a) Matthew 20:9

And when those hired about the eleventh hour came, each of them received a denarius.

(RSV)

Greek: denarion

RSV, NIV: a denarius

GNB: a silver coin

LV: $20.00

KJV: a penny

NEB: the full day’s wage (with footnote: literally, one denarius each)

b) Matthew 14:5

For this ointment might have been sold for more than three hundred denarii. (RSV)

Greek (lit.):

denarion triakosion

denarii three-hundred

RSV: three hundred denarii

GNB: three hundred silver coins

NIV: for more than a year’s wages (with footnote: literally, three hundred

denarii)

LB: a fortune

KJV three hundred pence

NEB thirty pounds (with footnote: literally, three hundred denarii).

c) John 11:18

Bethany was near Jerusalem about two miles off. (RSV)

27

Greek (lit.):

stadion dekapente

stadia fifteen

KJV: fifteen furlongs

RSV: about two miles (with footnote: literally, fifteen stadia)

NIV: less than two miles (with footnote: literally, fifteen stadia)

GNB: less than three kilometres

d) Acts 1:12

… from the mount called Olivet, which is near Jerusalem, a sabbath day’s journey away

Greek (lit.): sabbatou echon hodon

of-sabbath having way/path

RSV, and most other English translations: a sabbath day’s journey

GNB: about a kilometre away

28

CHAPTER 10: RHETORICAL QUESTIONS

10.1 STATEMENT, QUESTION, OR COMMAND?

At the beginning of the course, when the functions of language were discussed (1.1), we saw that three

of the functions of language are:

i. to give information

ii. to obtain information

iii. to stimulate actions in other people

In the most basic form of most languages, these three functions correspond to three major grammatical

classes:

statement (‘indicative’)

question ('interrogative’)

command (‘imperative’)

This correspondence between the function and the grammatical form, however, is by no means

invariable. In English, for example, it is possible to stimulate action (i.e. give a command) by using

any one of the three grammatical forms:

e.g.,

“Shut the window.” (imperative)

“Would you mind shutting the window?” (interrogative)

“I’d be glad if you would shut the window” (indicative)

10.2 QUESTIONS IN THE BIBLE

There are about 1,000 utterances which have question form in the original text of the New

Testament.

It is estimated that about 300 of these are ‘real’ questions, i.e. they are questions which ask for

information and which require an answer.

The remaining 700 ‘questions’ do not ask for information and do not, in most cases, require any

answer. Their function is rather to give information, including information about the speaker’s

attitudes and opinions. Sometimes they aim to stimulate a particular response in the hearer. Such

questions are called ‘rhetorical questions’.

e.g.,

Real question:

Mark 6:38*

And he said to them, “How many loves have you?”

(answered by) …”Five, and two fish.”

Rhetorical question:

Mark 8:36, 37*

“For what does it profit a man to gain the whole world and forfeit his life? For what can

a man give in return for his life?” (Notice that no answer is expected.)

10.3 FUNCTIONS OF RHETORICAL QUESTIONS IN THE BIBLE

Some common functions of rhetorical questions in the Bible are:

To emphasize a fact which is obviously true

Matthew 7:22

Lord, Lord, did we not prophesy in your name, and cast out demons in your name, and do

mighty works in

your name?

29

Mark 3:23

How can Satan cast out Satan?

1 Samuel 4:8

Woe to us! Who can deliver us from the power of these mighty gods?

1 Samuel 17:8

Am I not a Philistine, and are you not servants of Saul?

Notice that, in English, negative question form implies a positive statement, while positive question form

implies a negative statement.

To specify a particular condition under which something applies

James 5:13

Is any one among you suffering? Let him pray

Romans 13:3

Would you have no fear of him who is in authority? Then do what is good, and you will receive

his approval.

This type of rhetorical question can often be transformed into an ‘if’ clause without changing the

meaning:

e.g., If any one is suffering, let him pray.

To introduce a new topic, a new aspect of a topic

Psalm 15:1, 2

O Lord, who shall sojourn in thy tent? Who shall dwell on they holy hill? He who walks

blamelessly, and does what is right…

Notice how the two questions introduce the topic of the psalm, providing the setting for

the answer.

Mark 13:1, 2

…one of his disciples said to him, “Look, Teacher, what wonderful stones and what wonderful

buildings?” And Jesus said to him, “Do you see these great buildings? There will not be left

here one stone upon another…”

Here Jesus focuses on the topic of the destruction of Jerusalem and of the Temple by

using a question.

Luke 7:44

Then turning toward the woman he said to Simon, “Do you see this woman?…”

Study the total context of this passage, from 7:36—50, and notice how the question

form

is used to focus again on the woman, who has already been mentioned earlier in the

passage.

Romans 9:30

What shall we say, then? That Gentiles who did not pursue righteousness have attained it…

Notice how the expression “What shall we say then?” is used to indicate the conclusion

of one phase of the argument and the beginning of a new point. Look for other places in

the letter to the Romans were this expression or a similar form, is used in this way.

To express surprise

Mark 6:2 … and many who heard him were astonished, saying, “Where did this man

get all this? What is the wisdom given to him?”

To rebuke or exhort someone

Mark 4:40

Why are you afraid? Have you no faith?”

Mark 5:35

“Your daughter is dead, Why trouble the Teacher any further?”

To express uncertainty—

30

this type of question is often self-directed; it might be regarded as a genuine question. But any

question to

which the speaker himself supplies the answer is usually regarded as rhetorical.

Luke 12:17

… and he thought to himself, “What shall I do, for I have nowhere to store my crops?”

Luke 16:3

And the steward said to himself, “What shall I do, since my master is taking the stewardship

away from me?”

This list of functions is not exhaustive, nor is each function exclusive of the others. One question

may have more than one function at the same time. So each question must be studied carefully in

its context in order to discover its function(s).

Notice that real questions may also carry overtones of associative meaning (e.g.

surprise, rebuke), communicating the attitude of the speaker and sometimes suggesting

what he expects the response to be.

10.4 IMPLICATIONS FOR TRANSLATION

Having analysed the actual meaning of each rhetorical question in its context, the translator then has

to consider how best to transfer that meaning into the receptor language.

Different languages use rhetorical questions in different ways. Most languages do have rhetorical

questions, but these do not always have the same functions as those we have seen illustrated above. Some

languages use rhetorical questions much more frequently than other languages.

Therefore it is not possible to assume that a rhetorical question in the source text will necessarily be

best translated by a rhetorical question in the receptor language. The question form may not always

be appropriate.

Note how a dynamic translation such as the GNB quite often recasts rhetorical questions in another way

in order to bring out the actual meaning in the context more clearly.

e.g.,

1 Samuel 6:6

RSV (following the form of the Hebrew text)

After (God) had made sport of them, did not they let the people go, and they departed?

GNB Don’t forget how God made fools of them until they let the Israelites leave Egypt.

SUMMARY NOTE ON TRANSLATING RHETORICAL QUESTIONS

i. KEEP ALERT to recognize when a question form in the source text is rhetorical.

FOR EACH RHETORICAL QUESTION, CONSIDER WHAT IS THE MEANING OR

FUNCTION OF THAT QUESTION IN THAT CONTEXT IN THE SOURCE TEXT.

ii. THEN CONSIDER HOW THAT MEANING CAN BEST BE ACCURATELY,

CLEARLY AND NATURALLY EXPRESSED IN THE RECEPTOR LANGUAGE.

EXERCISES FOR CHAPTER 10

You are encouraged to look up the context of each passage, but you are not asked to recast

anything except the portions quoted below.

a) Matthew 11:16 “But to what shall I compare

this generation? It is like children

31

sitting in the market places . . .” ___________________

b) John 7:19 Did not Moses give you the law?

Yet none of you keeps the law. ___________________

c) John 8:53 Are you greater than our

father Abraham, who died? ___________________

d) John 13:6 Peter said to him, “Lord,

do you wash my feet?” ___________________

e) Luke 9:41 Jesus answered, “O faithless

and perverse generation, how long am I

to be with you and bear with you? ___________________

f) Romans 13:3, 4 Do you want to be free

from fear of the one in authority? Then

do what is right and he will commend you. ____________________

(NIV)

g) Romans 8:31 If God is for us, who is

against us? ____________________

h) 1 Corinthians 7:18 Was anyone at the time

of his call already circumcised? Let him

not seek to remove the marks of circumcision. ____________________

i) 1 Corinthians 12:17 If the whole body were

an eye, where would be the hearing? _____________________

j) Galatians 5:7 You were running well; who

hindered you from obeying the truth? _____________________

32

CHAPTER 11: FIGURES OF SPEECH: METAPHOR AND SIMILE

11.1 INTRODUCING METAPHOR AND SIMILE

A SIMILE is a figure of speech which involves a comparison.

e.g.,

The baby’s skin is as smooth as silk

He ran like the wind.

I’m as hungry as a hunter.

My feet are colder than ice.

His car rattles like a sack of tin cans.

Sugar is sweet, and so are you.

A METAPHOR is also a comparison. The only difference between a simile and a metaphor is that in a

simile the comparison is explicitly stated, usually by a word such as ‘like’ or ‘as’, while in a metaphor the

comparison is just implied.

e.g.,

METAPHOR:

Benjamin is a ravenous wolf. (Genesis 49:27)

SIMILE:

Benjamin is like a ravenous wolf.

11.2 ANALYSING METAPHORS AND SIMILIES

Both metaphor and simile involve three parts:

the TOPIC, i.e., the actual thing which is being talked about

the ILLUSTRATION, i.e., the thing to which the topic is compared

the POINT(S) OF SIMILARITY, i.e., the components of meaning which the topic and the

illustration have in common when compared.

Examples:

a)

For the simile, “the baby’s skin is a smooth as silk”,

the TOPIC is the baby’s skin

the ILLUSTRATION is silk

the POINT OF SIMILARITY is smooth

b)

For the simile, “like an arrow from a bow the child darted into the house”,

the TOPIC is the way that the child moved

the ILLUSTRATION is an arrow coming from a bow

the POINT OF SIMILARITY is (speed, directness)

c)

For the metaphor, “Benjamin is a ravenous wolf”,

the TOPIC is Benjamin

The ILLUSTRATION is a ravenous wolf

the POINT OF SIMILARITY is (dangerous, likely to attack, greedy)

You may find it helpful to use a sentence formula in identifying the three parts of a

metaphor or simile:

TOPIC is like ILLUSTRATION because POINT OF SIMILARITY

e.g.,

Benjamin is like a ravenous wolf because (he is dangerous and likely to attack.)

The way the child moved is like an arrow coming from a bow because (he moved quickly and

purposefully.)

11.4 TRANSLATING METAPHORS AND SIMILIES

As we have already seen the Point of Similarity between the Topic and the Illustration is quite often

left implicit. The clues to correct interpretation are found

33

(a) in the immediate context, or

(b) in the shared background knowledge of the speaker and the hearer.

When the message is translated, however, it is then being received by people whose cultural

background is different from that of the original giver of the message. There are some background

facts which the receivers of the original message knew (because they came from the same cultural

background as the giver of the message) but which the receivers of the translated message do not

know.

e.g.,

Micah 1:16 Make yourselves bald and cut off your hair,

for the children of your delight;

make yourselves as bald as the eagle,

for they shall go from you into exile.

An understanding of this passage depends on the knowledge that, in Hebrew culture,