Pediatric Motor Speech Disorders

advertisement

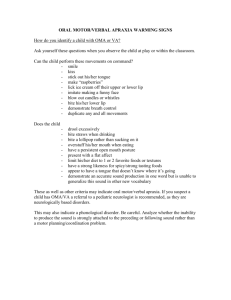

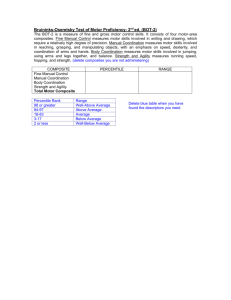

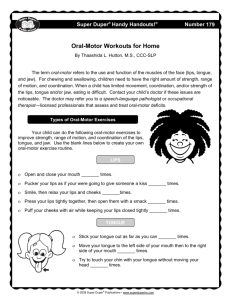

Pediatric Motor Speech Disorders Information Provided by: Cari L. Mutnick, MA, CCC-SLP Speech-Language Pathologist (321) 277-1384 Kickapoo23@aol.com Childhood Motor Speech Disorders When a child is learning to understand and use the sound system of language but is constrained in ability to plan, sequence, and/or control movements of muscle groups used to generate speech due to neurological and/or neuromuscular impairment. Typically children do not “grow out of” or are “cured” of physical basis of speech disorder (underlying impairment/chronic condition); but may be improved with therapy. Children with motor speech disorders demonstrate neuroplasticity. o Experiential learning can improve communicative function o Need more opportunities for this (not fewer) than other children o Treatment can capitalize on neuroplasticity of child and child’s communication on partners to improve communicative function Implications for children with severe speech delay and suspected Motor Speech Disorders: o Brain is not wired (yet) to move child through these developmental stages o Extra, focused stimulation and consequent opportunities for task specific practice are need to develop child’s neural connections to change speech sound input into actions of the speech mechanism to produce consonants, vowels and combinations for speech o Speech change involves both “unregulating” speech stress of brain and learning effective compensatory strategies Changing a Child’s Speech Patterns How to best capitalize on mechanisms of brain plasticity? o The importance of active attention to sensory input from the environment. Active engagement matters. o The importance of many opportunities for active learning that provide specific input back to areas of the brain where change is desired. Repetition and intensity matter. o The importance of mediated of mediated opportunities for learning to occur in “lifelike” contexts and enriched environments. To make effective changes in these children’s speech behaviors, they need: o Explicit, systematic, focused, frequent practice opportunities that encourage “talking” in general and that provide contexts and feedback on specific speech goals: Appropriate level for the child’s phonetic abilities and speech motor developmental level Enabling learning contexts (fun, enjoyable, motivating, etc.) Where child practices “speaking” to code meaning while engaging in communicative acts (social, routines, behavior regulation, joint attention, etc.) Key Role for Speech-Language Pathologists SLP’s have a key role in helping parents understand and maximize a child’s “brain plasticity” for learning speech . o Factors within the child o Factors within the environment o Factors related to the task Specific Motor Speech Disorder: Dysarthria Breakdown in execution of motor commands o Sending neural signals from brain out to muscle groups to execute motor plans and programs o Neuromuscular motor speech disorder o Abnormal neuromuscular function that disrupts execution of movements o Characterized by weakness, slowness, muscle tone abnormalities, reduced movement, coordination, and accuracy of muscle groups of the speech mechanism Speech Characteristics that Children w/ Dysarthria May Exhibit: o Short breath groups (few words per breath) o Abnormal voice quality (strained; breathy) and volume o Difficulty using contrastive stress (equal stress on all words) o Slow rate of speech movements and speaking rate o Nasal resonance and nasal air emission o Imprecise vowels/consonants overall o Particular difficulty with sounds that require more precise timing (speed) and accuracy o Overall sense that it requires effort to talk Therapy for Children with Dysarthria o Treatment begins following an evaluation with a speech-language pathologist to determine the severity of the problem and recommend an appropriate course of treatment o Therapy sessions may include oral-motor activities to increase coordination with the lips and tongue and respiration and breath control therapy to increase vocal quality and speech production o The primary goal of treatment is to improve overall communication skills by targeting a variety of functional areas including rate, breath support, oral-motor strength, and articulation skills. Examples of Oral Motor Exercises to Try at Home o Blowing Bubbles o o This is a great exercise for breath control as well as pursing lips for various sound production Blow a Kazoo This is an inexpensive tool that not only helps your breath control, but it will also help with vocal control as well. This is an effective activity because you have to hum to get any sound out of a kazoo. You can begin by making a simple humming sound, then as you progress, you can try to vary the pitch of your hum and even try to play a simple tune (like “Mary had a Little Lamb”). Using a Straw Practicing with a straw will obviously work on sucking skills, however, it also involves pursing those lips again. Thin liquids (if the child is able to take them) are good starters (water, juice, etc.). As you progress, you might want to try a thicker liquid like a milkshake. o o Tongue press For this exercise you will need a tongue depressor or a spoon. You will also need an adult to provide an “immovable force”. First have the child stick out their tongue. Have the object (spoon or tongue depressor) pressed against their tongue tip. Have the child push against the objects as hard as they can for a count of 5, then have them relax. Have the child try to do this 6-8 times in a row. Licking Ice Cream o If your child has a feeding or swallowing issue, do not do this exercise. Put some ice cream in a cone and let it melt a little. Then have the child practice using just their tongue (no lips) to lick the dripping ice cream. This is a great tongue exercise. Peanut Butter on the Lips Rub some peanut butter on the child’s lips and have them try to lip it all off. Make sure you apply the peanut butter from one corner of the mouth to the other. This will force the tongue to reach from side-to-side to lick the peanut butter off.