Counselor`s Handbook - the CLC Faculty and Staff Web Pages

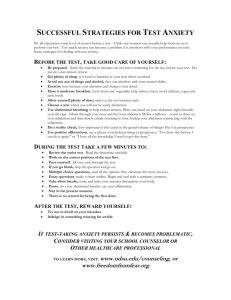

advertisement