Biodiversity Conservation of Rangeland

Biodiversity Conservation of Rangeland

Prasanna Yonzon

Resources Nepal GPO Box 2448, Kathmandu, Nepal

Introduction

Rangelands of Nepal comprise of grasslands, pastures, shrublands and other grazing areas. These play an important role in the country’s farming systems and are the major feed resource for livestock and the wild life. These areas are spread vertically on the Himalayan mountain systems and are very diverse. Thus we have a wide range of sub-tropical-temperatealpine and arid grazing areas which support very high biodiversity.

Distribution of Rangelands in Nepal

Inspite of their importance the rangeland of Nepal have not attracted the attention of researchers and the detailed accounts of their various aspects are not available. There is no comprehensive assessment of rangelands because of: 1) overlapping definitions of range, pasture, grassland, and other types of landuse that produce forage; 2) difficulties in estimating the amount of range use because of their remoteness; 3) intensive and extensive nature of herd movement patterns; and 4) no estimates of mountain agropastoralist households who depend on the rangelands. The only data available is from Land Resource Mapping Project (1986) based on landuse pattern. Total grazing area of Nepal usually referred to as grassland area, is estimated to cover about 1.7 million hectares, or 12 percent of total land area (Table 1). About 70% of the rangelands are situated in the western and mid-western regions and it is estimated that only 37% of the rangeland forage is actually available or accessible for livestock (LMP, 1993; Pariyar, 1998).

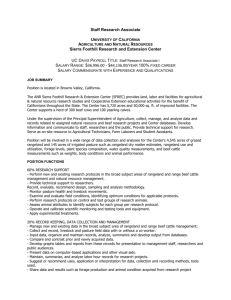

Table 1. Distribution of rangeland in Nepal (LRMP, 1986).

Physiographic Region Total Land Rangeland (grazing land)

Terai (tropical)

Area km 2

Area

(km 2 )

(percent)

21220 (14.39) 496.6

Total Land

(percent)

0.34

Grazing

Land

(percent)

2.92

Siwalik (subtropical)

Mid - Hills (temperate)

18790(12.74)

43503(29.50)

205.5

2927.8

0.14

1.98

1.21

17.20

High

(subalpine)

Mountain

High Himal (alpine)

Total

29002(19.66) 5071.3 3.44

34970(23.71) 8315.4 5.64

147485 17016.6 11.54

29.80

48.87

100.00

Rangeland in the High Mountain Protected Areas

The rangelands in the protected areas have not been properly addressed to and adequate management of these is lacking. Grazing lands in the high mountain parks are called ‘patans’ and cattle are allowed to graze in specific time on a rotational basis. However, population of cattle

6

has increased double fold and these are brought from other districts for grazing which has caused over grazing and fragmentation of grazing land within the protected areas.

At present the rangelands constitute 17,016.6 sq.km (11.54 % of total land area) and are slowly being metamorphosed into barren land. These areas are unique ecosystems and high level of endemism occurs here. Although the protected areas constitute 34.45 % of the total rangeland, there has not been a single R&D programme that has been successful in the last 25 years.

However, the protected area managers have prioritized preliminary studies on rangeland management in recent years.

The 16 protected areas (PA’s) have 5,862.88 km 2 as

rangelands (34.45 % of rangeland and 25.88

% of PAs) (Table 2)

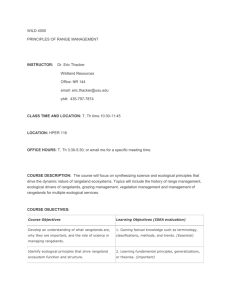

Table 2 Rangeland inside Protected Areas

Names

Annapurna Conservation Area

Total Area

( km

2

)

Rangeland

7629 2,519.68

Dhorpatan Hunting Reserve

Kanchenjunga Conservation Area

Khaptad National Park

Kosi Tappu Wildlife Reserve

Langtang National Park

Makalu-Barun National Park and Conservation

Area

Parsa Wildlife Reserve

Rara National Park

Royal Bardia National Park

1325 445.57

1650 283.97

225 16.27

175 29.86

1710 343.49

2330 646.32

499 .42

106 11.22

968 2.93

Royal Chitwan National Park

Royal Sukla Phanta Wildlife Reserve

Sagarmatha National Park

Shivapuri Watershed and Wildlife Reserve

Shey-Phoksundo National Park

Total

932 48.09

305 55.39

1148 219.62

97.38 5.88

3555 1234.17

22,654 5,862.88

Biodiversity and Endemism in the Rangelands

Some 246 species out of Nepal’s 5160 recorded flowering plant species are endemic to Nepal.

131 endemic plants (Shrestha, 1998) are known to occur in subalpine and alpine rangelands. This, therefore, suggests that these reservoirs possess enormous diverse genetic resources and could be landmark for the Nepal Himalayas. Of the 700 species of plants that have medicinal and aromatic properties 41 species have been identified as key species of which14 (34%) are known to occur in the rangelands. The medicinal plants are basically used for Ayurvedic therapy and have high values in Allopathic medicines as well.

7

Indicators of pyramidal type of diversity in the mammals can be encountered with elevation increment. Of Nepal’s twelve-mammalian order, nine are known to occur in the rangeland. Some

80 species of mammals are known to occur of which 8 are major wildlife species, they are Snow

Leopard, Grey Wolf, Tibetan Argali, Lynx, Brown Bear, Musk Deer, Red Panda and Tibetan

Antelope. Of these 4 are endangered and vulnerable.

Over 840 species of birds are known to occur in Nepal and they exhibit highest diversity in tropical and subtropical belt where 648 species are found. Only 413 bird species are reported to occur above 3000m altitude. Of these, only 19 species are known to breed in these high grounds.

Nine species are restricted to alpine rangeland of which 5 species have significant population in

Nepal (Inskipp, 1989).

Of over 20 indigenous breeds of livestock species that are found in Nepal, 8 endemic breeds

(40%) are from alpine region (Sherchand and Pradhan, 1998; Shrestha, 1998). Farmers alone have conserved this unique assemblage of gene pool that is adapted to severe environments and resistance to diseases. However, distribution and status of most livestock breeds is poorly known.

Interactions between wildlife and livestock also need to be better understood to assist pastoral development planning.

Although human activities have degraded wildlife habitat leading to the loss of biodiversity, primarily through poaching and trapping of wildlife and over-harvesting of herbs and medicinal plants throughout Nepal, several mountain-protected areas, perhaps, may safeguard rangeland biodiversity in them.

Management Issues

His Majesty’s Government (HMG) Nepal has given much focus on forests, agriculture, irrigation and water resources. However, there has been a dearth in policy towards addressing the rangelands. In the 60’s, planning of policies was primarily focused for food, water and energy.

The agropastoralists failed to make an impact as they were ignorant of the government policies and were in remote areas tending their herds.

Common properties have been misused due to lack of stewardship and ownership. The ranglelands have been largely degraded due to these factors. In some areas, rotational grazing is practiced while communities and individuals for which the herders have to pay a certain fee for grazing their cattle own some areas.

Historical Perspective of Rangeland Resource Development

Rangeland management has not been adequately addressed to by the HMG (Pariyar, 1998). Most of Nepal's initiatives have been approached through forage research and development. In the early 50’s cheese factories were established in central and eastern Nepal. Temperate cultivar evaluation cum forage production program was launched in 1953 and FAO's Pasture, Fodder and

Livestock Development Project was implemented in Nuwakot and Rasuwa Districts in the late

60's. Similarly establishing Pasture & Fodder Development Farm, Rasuwa in 1971 and Pasture

Development Project at Khumaltar in 1978 strengthened rangeland improvement programmes.

As external assistance continued until 1980's, USAID's Resource Conservation and Utilization

8

Projects (RCUP) and Swiss funded forage improvement works in Dolakha and Sindhupalchowk

(Basnyat, 1995) were implemented.

Profound changes have taken place primarily through expansion of agriculture into rangelands.

Transformation of traditional pastoral production systems and a general desiccation of alpine rangelands due to climatic changes are perhaps modifying vegetation composition and reducing plant productivity (Miller, 1993). The ensuing political changes in Tibet (China) after 1959, disrupted centuries old transhumance patterns. Since then, there were several negotiations on the issues related to rangeland availability for both Nepali and Tibetan herds. In 1983, the two governments agreed that animal migration from both countries would be completely stopped by

April 1988. These political, social, economic, and ecological transformations have cumulatively degraded many previously remote pastoral areas and their environment.

Realizing the severe impacts of such closure, as well as shortage of fodder, Nepal initiated the

Northern Areas Pasture Development Programme in 1985 focusing towards range management and fodder development in four "Critical" districts: Humla, Mustang, Sindhupalchowk and

Dolakha, and six "emerging" forest/feed crisis districts: Manang, Dolpa, Gorkha, Mugu,

Sankhuwasabha and Taplejung. Between 1987 - 1990, the High Altitude Pasture Development

Project (1987 - 1990) provided extension support while the Himalayan Pasture & Fodder

Research Network (1987 - 1990) supported research. These two FAO/UNDP activities supported

HMG's district level forage improvement Programmes to ease the fodder crisis.

To alleviate poverty and restore degraded hill slopes in 12 districts through access to credit, inputs and technological assistance to poor farmers, the Hills Leasehold Forestry and Forage

Development Project (1992) was jointly implemented by the Department of Forest, Department of Agriculture, Nepal Agriculture Research Council and the Agriculture Development Bank of

Nepal. Institutional interactive relationships between researcher, technician and farmer, public and private sectors are being developed.

Overview of Policy Measures

Sustainable rangeland development requires appropriate policies. Policies in the past have largely ignored mountain rangelands due to the fact that the Government has failed to recognize the importance of rangelands in its 5 year Plans for the last forty years. There is a general perception that rangelands are overgrazed and that modern techniques are needed to improve the conditions.

However, livestock planners who generally ignore the complexities of rangeland systems often prescribe the “improved” grazing systems. Furthermore, agricultural and forestry policies have usually neglected the role of rangeland biodiversity in development and their potential contribution to mountain economic growth.

Ownership of rangelands rests with the Ministry of Forest and Soil Conservation (MFSC), while their utilization by local communities is associated with the Ministry of Agriculture (MOA). The

Department of Livestock Services, Department of Agriculture and Nepal Agricultural Research

Council has carried out pasture development and livestock improvement. The northern rangelands are located within protected areas under the jurisdiction of the Department of National

Parks and Wildlife Conservation (DNPWC) and the King Mahendra Trust for Nature

Conservation (KMTNC). As rangelands are multisectoral because of their many uses, there is a

9

distinct need for MOA and MFSC to jointly develop rangeland policy and appropriate management strategies in consultation with local communities.

Rangeland Tenure System and Human Use

Rangelands in the High Mountains of Nepal do not serve only as animal feed resources, but also as catchment areas for a number of river systems that flow down to the Mid Hills and Terai.

Although mountain slopes forming the catchment of principal perennial river systems are under heavy grazing pressure, animal husbandry and pasturelands are central to the socioeconomy of the high altitude areas of Nepal. Being food-deficit areas, livestock, barter and trade, and seasonal migration are the evolved strategies of the mountain communities. Even the centuries old Trans-Himalayan (Nepal -Tibet) trade has also depended on animal husbandry for transportation.

Indigenous pasture management systems have been structured primarily from local knowledge and experiences. Many pastoral systems involve moving livestock herds following seasonal patterns for forage or water sources. For these reasons, traditional rights to pasture lands are held.

Most pastoral families and groups have developed these rights into institutions to regulate the use of rangelands, the scheduling of movements within the group and the temporary or permanent closure of certain areas to grazing. Therefore, indigenous management systems have been an important element in the social structure of the local populations for effectively maintaining productivity at levels sufficient to meet local needs.

Many studies have documented the sophistication of traditional knowledge. However, they are not without shortcomings. Traditional technologies were developed under conditions of relatively vast resources, sparse human population and low livestock pressure. Much of the traditional knowledge has been lost or is no longer applicable because of population growth, commercialization of livestock and rangeland products and services. Yet, traditional knowledge can be modified with modern technologies to meet development needs.

Rangeland Loss and Major Threats

The rangelands provide 36 % of the total feed requirement for livestock in the country. Estimated forage production of high altitude grazing is comparatively higher including their carrying capacity (Table 3). However, enormous grazing pressure exists and estimates suggest that there are nine times more grazing animals than the land can viably support. This high grazing pressure depletes the palatable species, especially legume component. With extremes of wind, rainfall, and temperature, arid mountain rangelands are especially prone to the process of verification, or drying out, that can be caused or accelerated by overgrazing.

The 20 - year Agriculture Perspective Plan period (APROSC, 1995) projects that the demand for the growing livestock raising will be 25.6 million MT, which means massive efforts have to be concentrated on the production of cultivated fodder and optimum management of forest and pasture land to make up the deficit of 7.6 million MT. As the availability of quality fodder will remain a major limiting factor, the contribution of cultivated fodder and pastures has to be boosted up from 26% to 49% (Sherchand and Pradhan, 1998).

10

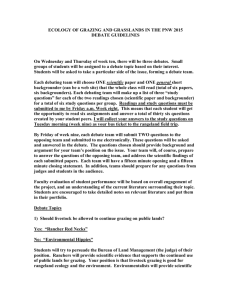

Table 3. Productivity of rangelands (Miller, 1989; Rajbhandari and Shah, 1981)

Rangeland Area

(km

2

)

Productivity

(TDN. t/ha)

Carrying capacity

Stocking rate

(LU/ha)

Subtropical & Temperate 6293

Alpine 10141

0.58

1.54

0.54

1.42

7.07

0.64

Steppe 1875 0.06

TDN = total digestible nutrient; LU = livestock unit

0.09 1.19

Most mountain rangeland ecosystems are relatively susceptible to degradation such as arid regions and high mountain pasture communities because they are less resilient to disruption than subtropical ecosystems. Moderately degraded range can usually be restored over time through integrated management systems. Severely degraded rangelands may require both investment and techniques to make them economically viable and ecologically restored.

Building partnership for strengthening rangeland management

Limited support for pastoral development and rangeland resource management without understanding range ecosystem dynamics, pastoral production practices, and biodiversity conservation in the past has led to loss of biodiversity. Rangeland ecosystem is diverse and issues that relate to policy, management, institutional, technical and socio-economics can be looked upon at three sectoral levels; private sector, communities and public.

In the private sector, poor land allocation associated with very poor quality (productivity) of livestock in large numbers are found to be the major issues. All these stem either from degraded or overgrazed rangelands including burning of large areas annually, poor economy and lack of markets, and absence of management support.

At community level, many rangelands face the crisis of common property resources. There is a distinct need for awareness, and restrengthening traditional community organization.

In the implementation sector (public), lack of proper policy together with integrated development plans; technical support and trained manpower are considered important. Lack of institutional networking and frequent restructuring and organizational changes are also distinct. Long-term integrated research - development - extension projects are non-existent and more involvement of international non-government organizations and communities are needed.

Conclusion

The subtropical and temperate rangelands are complementary to agriculture. Historically, forage

-related programmes were concentrated in these two regions. Unfortunately, policy makers and development agencies because of their remoteness, high altitude locations, harsh climate, and sparse settlements have neglected high altitude rangelands. Nepal's high altitude rangelands need a major focus because they contain biodiversity with exceptionally high number of endangered species. Therefore, they need a greater support to maintain existing biodiversity, rural livelihood, and viable economy.

11

To integrate needs and perceptions of local pastoral communities and conservation of biodiversity, development of a national rangeland policy is suggested where legislation is made comprehensive with institutional mandate and clears organizational arrangement.

Conservation of rangelands require three priority actions within an integrated range management encompassing ecosystem approach and technology and approaches to grazing management

(ICIMOD, 1998). Along this well-thought strategy, the rangeland plan of action should include 1) rangeland biodiversity; 2) pastoral development; and 3) forage and fodder development. Above all, lessons learnt from the past four decades calls for pastoralists and development workers to interact and adopt more reliance on local knowledge seeking a cooperative search for appropriate technologies and local organizational structures for development.

References

1.

APROSC. 1995. Agriculture Perspective Plan. Agriculture Project Services

Center and John Mellor Associates, Inc. Kathmandu Archer, A. C. 1987. Himalayan

Pasture and Fodder Research Network. RAS/ 79/121 Consultant's Report. Kathmandu,

Nepal.

2.

Basnyat N.B.1995. Background paper on present state of Environment with

Respect to Rangeland Sustainability -NEPPAP II.

3.

ICIMOD. 1998. Status of Himalayan Rangelands and Their Sustainable

Management. Paper for Regional Expert Meeting on Rangelands and Pastoral

Development in the Hindu Kush - Himalayan Mountain Region, ICIMOD, Nepal.

4.

Inskipp, C. 1989. Nepal’s forest birds: Their status and conservation. ICBP

Monograph No. 4. U.K.

5.

LRMP. 1986. Survey Department, HMG and Kenting Earth Sciences.

Kathmandu.

6.

LMP.1993. Livestock Master Plan. The livestock Sector volume III , Asian

Development Bank/ANZDECK /APROSC.

7.

Miller, D. J. 1993. Grazing Lands in the Nepal Himalayas. Draft. USAID Nepal,

Kathmandu.

8.

Pariyar, D. 1998. Rangeland resource biodiversity and some options for their improvements.

National Biodiversity Action Plan. Kathmandu.

9.

Serchand, L. and S. L. Pradhan. 1998. Domestic Animal Genetic Resource Management and

Utilization in Nepal. National Biodiversity Action Plan. Kathmandu.

10.

Shrestha, N. P. 1998. Livestock and Poultry Genetic Resource Conservation in Nepal.

National Biodiversity Action Plan. Kathmandu.

12