SUSANNE

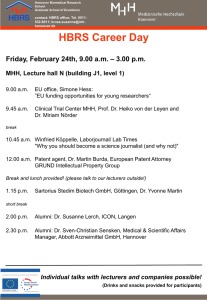

advertisement

THE SUSANNE CORPUS Release 1, 6th September 1992 Geoffrey Sampson School of Cognitive & Computing Sciences University of Sussex Falmer, Brighton BN1 9QH, England geoffs@uk.ac.susx.cogs INTRODUCTION The SUSANNE Corpus has been created, with the sponsorship of the Economic and Social Research Council (UK), as part of the process of developing a comprehensive NLP-oriented taxonomy and annotation scheme for the (logical and surface) grammar of English.[1] The SUSANNE scheme attempts to provide a method of representing all aspects of English grammar which are sufficiently definite to be susceptible of formal annotation, with the categories and boundaries between categories specified in sufficient detail that, ideally, two analysts independently annotating the same text and referring to the same scheme must produce the same structural analysis. The SUSANNE scheme may be likened to a "Linnaean taxonomy" of the grammatical domain: its aim (comparable to that of Linnaeus's eighteenth-century taxonomy for the domain of botany) is not to identify categories which are theoretically optimal or which necessarily reflect the psychological organization of speakers' linguistic competence, but simply to offer a scheme of categories and ways of applying them that make it practical for NLP researchers to register everything that occurs in real-life usage systematically and unambiguously, and for researchers at different sites to exchange empirical grammatical data without misunderstandings over local uses of analytic terminology. On reasons why such a scheme is needed at the present juncture in NLP research, see e.g. Sampson (1992, forthcoming). Note that a sharp distinction is drawn here between the terms "scheme" and "system". A "parsing scheme", or "analytic scheme", refers to a range of notations and guidelines for using them which prescribe to a human analyst what the appropriate grammatical annotation for a language example should be. A parsing "system" on the other hand refers to a software system which automatically produces analyses (according to some parsing scheme) of input language examples. A parsing scheme defines the target which a parsing system hits (or misses). The SUSANNE Corpus represents part of the definition of a parsing scheme. It has been produced largely manually, not as the output of an automatic parsing system. The SUSANNE analytic scheme is defined in detail in a book by myself, ENGLISH FOR THE COMPUTER, forthcoming from Oxford University Press. The Chairman of the Analysis and Interpretation Working Group of the US/EC-sponsored Text Encoding Initiative has proposed its adoption as a recognised TEI standard. The SUSANNE scheme aims to specify annotation norms for the modern English language; it does not cover other languages, although it is hoped that the general principles of the SUSANNE scheme may prove helpful in developing comparable taxonomies for these. Regrettably, Release 1 of the SUSANNE Corpus is not a "TEI-conformant" resource, though aspects of the annotation scheme have been decided in such a way as to facilitate a move to TEI conformance in later releases. The working timetable of the Initiative meant that relevant aspects of the TEI Guidelines were not yet complete at the point when the SUSANNE Corpus was ready for initial release; delaying this release would have been unfortunate. The brief description of the SUSANNE Corpus which follows cannot replace the very detailed statements to be found in ENGLISH FOR THE COMPUTER, and any user aiming to do serious work with the Corpus or its annotation scheme would need to consult the book. Nevertheless, it may be useful to have a summary statement included with the electronic Corpus. The present SUSANNE annotation scheme originated in work carried out by myself in collaboration with Professor Geoffrey Leech FBA and others in the years 1983-85 to produce a database of manually analysed sentences from the LOB Corpus of written British English, as a source of statistics for probabilistic automatic-parsing techniques; this database, which has not been (and will not now be) published, is described in Garside et al. (1987: ch. 7). The annotation scheme of this "Lancaster-Leeds Treebank" represented surface grammar only, without indications of logical form. It subsequently seemed desirable to extend this scheme to include methods for representing logical grammar, and to refine both surface and logical aspects of the annotation scheme by applying it to a larger body of texts. The only way that a parsing scheme can in practice be made increasingly adequate is in the way that the English Common Law develops, by collecting and systematizing the body of precedents generated through detailed consideration of more and more individual cases that arise in real life. Accordingly, Project SUSANNE took a subset of the Brown Corpus of written American English which had been manually analysed by Alvar Elleg<aring>rd's group at Gothenburg (Elleg<aring>rd 1978), and reworked the annotations in this under-used resource in order to turn them into a scheme consistent with that used in the Lancaster-Leeds Treebank but including specifications of logical as well as surface structure: several categories of information not indicated in either Lancaster-Leeds or Gothenburg schemes were also added.[2] (On Brown and LOB Corpora, see e.g. Garside et al. (1987: 4-5).) The finished SUSANNE parsing scheme has thus been developed on the basis of samples of both British and American English. It is oriented chiefly towards written language; however, on another project sponsored by the Royal Signals and Radar Establishment[3] my team produced extensions to the SUSANNE scheme for annotating the distinctive grammatical phenomena of spoken English, and these extensions are specified in ENGLISH FOR THE COMPUTER (though they are not used in the SUSANNE Corpus and are not discussed further here). It should be noted also that the scheme has emerged through a process of detailed critical discussion of analytic standards by some ten people over a decade; apart from myself, the leading role in the early years of these discussons was taken by Geoffrey Leech, whose standing as an English grammarian needs no emphasis. The SUSANNE Corpus itself comprises an approximately 128,000-word subset of the Brown Corpus of American English, annotated in accordance with the SUSANNE scheme. The original motives for producing this database included that of providing better statistics for probabilistic parsing; but in this respect Project SUSANNE was overtaken after its inception by projects (notably Mitchell Marcus's Pennsylvania Treebank project, cf. Marcus & Santorini (forthcoming)) which have used quasi-industrial methods to generate far larger bodies of grammatically-analysed material. However, the SUSANNE scheme may be unparallelled in the extent to which its categories have been refined and tested through detailed consideration of the almost endless small quirks of the texts to which they have been applied, and in the degree of precision to which the resulting guidelines for using the categories have been documented -- thus defining analytic standards which permit annotation of future material to be extremely self-consistent. Accordingly the SUSANNE Corpus is offered to the research community primarily as a demonstration of the application of the parsing scheme, evidencing the fact that the scheme has survived the test of experience rather than being a merely aprioristic system. The SUSANNE Corpus functions, as it were, like a collection of type specimens appended to a botanical taxonomy. Although the accompanying first release of the SUSANNE Corpus has undergone considerable proof-checking, it unquestionably still contains many errors. I intend to correct these in future releases; I shall be extremely grateful if users discovering errors will log these and send details to me, preferably by post rather than e-mail. STRUCTURE OF THE CORPUS The SUSANNE Corpus consists of 64 files (apart from this documentation file), each containing an annotated version of one 2000+ word text from the Brown Corpus. Files average about 83 kilobytes in size, thus the entire Corpus totals about 5.3 megabytes. The file names are those of the respective Brown texts, e.g. A01, N18. Sixteen texts are drawn from each of the following Brown genre categories: A G J N press reportage belles lettres, biography, memoirs learned (mainly scientific and technical) writing adventure and Western fiction The Corpus thus samples each of the four broad genre groups established on the basis of word-frequency data by Hofland & Johansson (1982: 27).[4] Each file has a line (terminating in a newline character) for each "word" of the original text; but "words" for SUSANNE purposes are often smaller than words in the ordinary orthographic sense, for instance punctuation marks and the apostrophe-s suffix are treated as separate words and assigned lines of their own. (For details on the rules by which orthographic words are segmented, as well as on all other analytic matters mentioned below, see ENGLISH FOR THE COMPUTER.) Each line of a SUSANNE file has six fields separated by tabs (that is, there is one tab after each of fields 1 to 5, but a newline after field 6). Each field on every line contains at least one character. The six fields on each line are: 1 2 3 4 5 6 reference status wordtag word lemma parse Apart from the tab and newline characters used to structure fields and records, all bytes in each of the 64 SUSANNE files are drawn from a subset of the 94 graphic character allocations of the International Reference Version ("IRV") of ISO 646:1983 "Information Processing -- ISO 7-bit coded character set for information interchange", from hexadecimal 21 (exclamation mark) to hex 7E (tilde). These codes are assumed for SUSANNE purposes to represent the graphic symbols assigned by the IRV system. Twelve members of the IRV character set are not used in the Corpus, namely (all codes hexadecimal): 23 24 27 2F 5C 5E 5F 60 7B 7C 7D 7E gate generalized currency unit prime solidus reverse solidus circumflex underline grave opening curly bracket vertical bar closing curly bracket tilde The space character, hex 20, which is classified by ISO 646 as a control code also does not occur in the SUSANNE Corpus. Where text characters cannot be adequately represented directly within the resulting 82-member character set, they are represented by entity names within angle brackets. Where possible these are drawn from Appendix D to ISO 8879:1986, "Information Processing -- Text & Office Systems -Standard Generalized Markup Language (SGML)". For instance, "<eacute>" stands for lower-case "e" with acute accent. Symbols in angle brackets are used also to represent such things as typographical shifts, which for purposes of grammatical analysis are conveniently represented as items within the word-sequence: e.g. "<bital>" stands for "begin italics". REFERENCE FIELD The reference field contains nine bytes which give each line a reference number that is unique across the SUSANNE Corpus, e.g. "N06:1530t". The first three bytes (here N06) are the file name; the fourth byte is always a colon; bytes 5 to 8 (here 1530) are the number of the line in the "Bergen I" version of the Brown Corpus on which the relevant word appears (Brown line numbers normally increment in tens, with occasional odd numbers interpolated); and the ninth byte is a lower-case letter differentiating successive words that appear on the same Brown line. (SUSANNE lines are lettered continuously from "a", omitting "l" and "o".) STATUS FIELD The status field contains one byte. The letters "A" and "S" show that the word is an "abbreviation" or "symbol", respectively, as defined by Brown Corpus codes (Francis & Ku<ccaron>era 1989: 12). The letter "E" shows that the word is (or is part of) a misprint or solecism in the original text (details are logged in ENGLISH FOR THE COMPUTER). On the great majority of lines, to which none of these three categories apply, the status field contains a hyphen character. WORDTAG FIELD The SUSANNE wordtag set is based on the "Lancaster" tagset listed in Garside et al. (1987: Appendix B); additional grammatical distinctions have been drawn in this set, and these are indicated by suffixing lower-case letters to the Lancaster tags. For instance, "revealing" is tagged "VVG" (present participle of verb) in the Lancaster scheme, but as "VVGt" (present participle of transitive verb) in the SUSANNE scheme. Apart from the lower-case extensions, the wordtags are normally identical to the Lancaster tags: punctuation marks are assigned alphabetical tags beginning Y... (e.g. YC for comma), and the dollar sign which appears in some Lancaster tags for genitive words is replaced by G (e.g. GG for the apostrophe-s suffix), so that the modified Lancaster tags always consist wholly of alphanumeric characters, beginning with two capital letters. (In a few cases, tags from the Lancaster set have been merged or eliminated from the SUSANNE scheme in the light of experience.) The tag YG appears in the wordtag field to represent a "trace" -- the logical position of a constituent which has been shifted elsewhere, or deleted, in the surface grammatical structure. The SUSANNE tagset comprises 352 distinct wordtags, not counting tags for elements of "grammatical idioms" (see below); a few of these wordtags never occur in the SUSANNE Corpus. The wordtags are listed, and their application rigorously defined, in ENGLISH FOR THE COMPUTER -- in the case of closed wordclasses, by enumeration of their members, and in the case of open classes by rules for choice between alternative tags. These rules refer to information in a specified published dictionary (the OXFORD ADVANCED LEARNER'S DICTONARY OF CURRENT ENGLISH, 3rd edition). WORD FIELD The word field contains a segment of the text, often coinciding with a word in the orthographic sense but sometimes, as noted above, including only part of an orthographic word. In general the word field represents all and only those typographical distinctions in the original documents which were recorded in the Brown Corpus (Francis & Ku<ccaron>era 1989: 10-15), though in certain cases the SUSANNE Corpus has gone behind the Brown Corpus to reconstruct typographical details omitted from Brown. Certain characters have special meanings in the wordfield, as follows: + (occurs only as first byte of the wordfield) shows that the contents of the field were not separated in the original text from the immediately-preceding text segment by whitespace (e.g. in the case of a punctuation mark, or part of a hyphenated sequence split over successive SUSANNE lines); - the line corresponds to no text material (it represents the "trace" for a grammatically-moved element); <...> enclose entity names for special typographical features, as discussed above, either taken from ISO 8879:1986 Appendix D or created for the SUSANNE Corpus -- for instance "<pand>" stands for "either plus sign or ampersand", since the Brown Corpus makes no distinction between these characters. LEMMA FIELD The lemma field shows the dictionary headword of which the text word is a form: the field shows base forms for words which are inflected in the text, and eliminates typographical variations (such as sentenceinitial capitalization) which are not inherent to the word but relate to its use in context. (In the case of "words" to which the dictionary-form concept is inappropriate, e.g. numerals and punctuation marks, the lemma field contains a hyphen.) Orthographic forms in the lemma field are those of a specified dictionary (the OXFORD ADVANCED LEARNER'S DICTIONARY OF CURRENT ENGLISH, 3rd edition). Project SUSANNE aimed also to indicate the senses which polysemous words bear in context, via codes relating word-tokens to numbered subsenses in a specified dictionary. The book ENGLISH FOR THE COMPUTER provides a detailed coding scheme for representing this information. Unfortunately, this aspect of the project's output proved to contain a number of inadequacies, and the information does not appear in Release 1 of the Corpus. It is hoped to include it in later releases. PARSE FIELD The contents of the sixth field represent the central raison d'<ecirc>tre of the SUSANNE Corpus. They code the grammatical structure of texts as a sequence of labelled trees, having a leaf node for each Corpus line. Each text is treated as a sequence of "paragraphs" separated by "headings". A "paragraph" normally coincides with an ordinary orthographic paragraph; a "heading" may consist of actual verbal material, or may be merely a typographical paragraph division, symbolized "<minbrk>" in the word field. Conceptually, the structure of each paragraph or heading is a labelled tree with root node labelled "O" ("Oh" for a heading), and with a leaf node labelled with a wordtag for each SUSANNE word or trace, i.e. each line of the Corpus. There will commonly be many intermediate labelled nodes. Such a tree is represented as a bracketed string in the ordinary way, with the labels of nonterminal nodes written "inside" both opening and closing brackets (that is, to the right of opening brackets and to the left of closing brackets). This bracketed string is then adapted as follows for inclusion in successive SUSANNE parse fields. Wherever an opening bracket immediate follows a closing bracket, the string is segmented, yielding one segment per leaf node; and within each such segment, the sequence opening-bracket + wordtag + closing-bracket, representing the leaf node, is replaced by full stop. Thus each parse field contains exactly one full stop, corresponding to a terminal node labelled with the contents of the wordtag field, sometimes preceded by labelled opening bracket(s) and sometimes followed by labelled closing bracket(s), corresponding to higher tagmas which begin or end with the word on the line in question. Brackets are square except in the case of nodes immediately dominating the "trace" wordtag YG, which are represented with angle brackets. Nonterminal node labels in the SUSANNE scheme contain up to three types of information: a FORMTAG, a FUNCTIONTAG, and an INDEX, in that order. In a label containing a formtag and one or both of the other two elements, a colon separates the formtag from the other elements. A functiontag is always a single alphabetic character, and an index is a sequence of three digits; restrictions on valid combinations of elements within a node label mean that complex labels can always be unambiguously decomposed into their elements. RANKS OF CONSTITUENT Apart from nodes immediately dominating traces, all node have labels including formtags, which identify the internal properties of the word or word-sequence dominated by the node. The shape of a parse-tree is defined in terms of a hierarchy of formtag ranks: 1 wordlevel formtags (begin with two capital letters; formtags of all other ranks begin with one capital and contain no further capitals) 2 phraselevel formtags (begin with one of: N V J R P D M G) 3 clauselevel formtags (begin with one of: S F T Z L A W) 4 rootlevel formtags (begin with one of: O Q I) Each grammatical clause, whether consisting of one or more words, is given a node labelled with a clauselevel formtag. Each immediate constituent of a clause, whether there are one or more such constituents and whether the constituent consists of one or more words, is given a node labelled with a phraselevel formtag, unless the constituent belongs to a wordlevel category that has no corresponding phraselevel category (e.g. punctuation marks, conjunctions), or to a rootlevel category (e.g. a direct quotation, formtagged Q). Thus a clause consisting of one verb will be assigned a clauselevel formtag (e.g. Tg for presentparticiple clause) which singularily dominates a phraselevel formtag (e.g. Vg for "verb group beginning with present participle") which in turn singularily dominates a wordlevel formtag (e.g. VVGi for "present participle of intransitive verb"). Other than by these rules, and in certain other limited circumstances specified in ENGLISH FOR THE COMPUTER, singulary branching does not occur. An intermediate phraselevel node is inserted between a higher phraselevel node and a sequence of words dominated by it only if two or more of those words form a coherent constituent within the higher phrase. A clause which fills a slot standardly filled by a phrase (e.g. a nominal clause as subject or object) will not have a phrase node above the clause node unless the clause proper is preceded and/or followed by modifying elements that are not part of the clause. Detailed rules for deciding constituency in various debatable cases, for placing items such as punctuation marks within parse trees, etc. are laid down in ENGLISH FOR THE COMPUTER. FUNCTIONTAGS AND INDICES Functiontags, identifying roles such as surface subject, logical object, time adjunct, are assigned to all immediate constituents of clauses, except for their verb-group heads and certain other constituents for which function labelling is inappropriate. Indices are assigned to pairs of nodes to show referential identity between items which are in certain defined grammatical relationships to one another. For instance, a phrase raised out of a lower clause to act as object in a higher clause, as in "John expected Mary to admit it", will be assigned an index identical to that assigned to the trace showing the logical position of the item in the lower clause. The (artificial) example quoted would be represented as: [Nns:s John] expected [Nns:O999 Mary] [Ti:o <s999 TRACE> to admit [Ni:o it]] -- where the index 999 shows that the trace acting as logical subject (symbolized s) of the "admit" clause is coreferential with "Mary" which acts as surface object (O) of the "expected" clause; the logical object (o) of the "expected" clause being the infinitival subordinate clause (Ti). In some cases, movement rules displace a constituent into a tagma within which it has no grammatical role (for instance, an adverb which is logically a clause constituent may interrupt the verb group -- sequence of auxiliary verbs and main verb -- of the clause): in such cases the functiontag is G ("guest"). Constituents which do not logically belong below the node which immediately dominates them in surface structure are always given G functiontags and indices linking them to their logical position. With that exception (and with one other exception not discussed here relating to co-ordination), functiontagging is used only for immediate constituents of clauses. ENGLISH FOR THE COMPUTER lists the categories of surface/logical-grammar discordance which are represented by the SUSANNE scheme, and the approved methods of representing them. The SUSANNE analysis is always chosen so as to be as far as possible neutral as between alternative linguistic theories. THE FORMTAGS The SUSANNE formtags are as follows: Rootlevel Formtags O Oh Ot Q I Iq Iu paragraph heading title (e.g. of book) quotation interpolation tag question scientific citation Clauselevel Formtags S Ss Fa Fn Fr Ff Fc Tg Ti Tn Tf Tb Tq Z L A W main clause quoting clause embedded within quotation adverbial clause nominal clause relative clause "fused" relative comparative clause present participle clause infinitival clause past participle clause "for-to" clause "bare" nonfinite clause infinitival relative clause reduced ("whiz-deleted") relative clause other verbless clause special "as" clause "with" clause Phraselevel Formtags N V J R P D M G noun phrase verb group adjective phrase adverb phrase prepositional phrase determiner phrase numeral phrase genitive phrase The various phrase categories take lower-case subcategory symbols which can be combined in any meaningful combination (e.g. the verb group "must have been noticed" would be formtagged "Vcfp"). The phrase subcategories are: Vo Vr Vm Va Vs Vz Vw operator section of verb group, when separated from remainder of V e.g. by subject-auxiliary inversion remainder of V from which Vo has been separated V beginning with "am" V beginning with "are" V beginning with "was" V beginning with other 3rd-singular verb V beginning with "were" Vj Vd Vi Vg Vn Vc Vk Ve Vf Vu Vp Vb Vx Vt V beginning with "be" V beginning with past tense infinitival V V beginning with present participle V beginning with past participle V beginning with modal V containing emphatic DO negative V perfective V progressive V passive V V ending with BE V lacking main verb catenative V Nq Nv Ne Ny Ni Nj Nn Nu Na No Ns Np "wh-" N "wh...ever" N "I/me" head "you" head "it" head adjective head proper name unit noun head marked as subject marked as nonsubject singular N plural N Jq Jv Jx Jr Jh "wh-" J "wh...ever" J measured absolute J measured comparative J postmodified J Rq Rv Rx Rr Rs Rw "wh-" R "wh...ever" R measured absolute R measured comparative R adverb conducive to asyndeton quasi-nominal adverb Po Pb Pq Pv "of" phrase "by" phrase "wh-" P "wh...ever" P Dq Dv Ds Dp "wh-" D "wh...ever" D singular D plural D Ms M headed by "one" NON-ALPHANUMERIC FORMTAG SUFFIXES Formtags may also contain non-alphanumeric symbols, including: ? * % ! " interrogative clause imperative clause subjunctive clause exclamatory clause or other item vocative item Other non-alphanumeric symbols represent co-ordination structure. Under the SUSANNE scheme, second and subsequent conjuncts in a co-ordination are analysed as subordinate to the first conjunct; thus a co-ordination of the form: chi, psi, and omega (whatever the grammatical rank of the word-sequences chi, psi, etc.) would be assigned a structure of the form: [chi, [psi], [and omega]] The formtag of the entire co-ordination is determined by the properties of the first conjunct (except for singular/plural subcategories in the case of phrase categories to which these apply); the later conjuncts (which will often be transformationally reduced) have nodes of their own whose formtags mark them as "subordinate conjuncts". The following symbols relate to co-ordination (and apposition) structure: + @ & subordinate conjunct introduced by conjunction subordinate conjunct not introduced by conjunction appositional element co-ordinate structure acting as first conjunct within a higher co-ordination (marked in certain cases only) Co-ordination is recognised as occurring between words as well as between higher-rank tagmas. Therefore nonterminal nodes may have formtags consisting of wordtags followed by co-ordination symbols, thus (using "WT" to stand for an arbitrary wordtag): WT& WT+ WT- co-ordination of words conjunct within wordlevel co-ordination that is introduced by a conjunction conjunct within wordlevel co-ordination not introduced by a conjunction (A wordlevel co-ordination always takes an ampersand on its formtag; phrase or clause co-ordinations do so only in very restricted circumstances.) Also, certain sequences of orthographic words, in certain uses, are regarded as functioning grammatically as single words ("grammatical idioms"). For instance, "none the less" would normally be treated as a grammatical idiom, equivalent to an adverb (for which the wordtag is RR). In such cases, the nonterminal node dominating the sequence has a formtag consisting of an equals sign suffixed to the corresponding wordtag; and the individual words composing the grammatical idiom are not wordtagged in their own right, but receive tags with numerical suffixes reflecting their membership of an idiom. (The sequence "none the less" would be formtagged RR=, and the words "none", "the", and "less" in this context would be wordtagged RR31 RR32 RR33.) ENGLISH FOR THE COMPUTER includes exhaustive listings of closed-class grammatical idioms. Note that formtags of the forms WT& WT+ WT- WT= rank as wordlevel formtags for the purposes of determining tree structure as discussed above. THE FUNCTIONTAGS Functiontags divide into COMPLEMENT and ADJUNCT tags: broadly, a given complement tag can occur at most once in any clause, but a clause may contain multiple adjuncts of the same type. The scheme of adjunct categories has been developed from the classification of Quirk et al. (1985). Complement Functiontags s o S O i u e j a n z x G logical subject logical direct object surface (and not logical) subject surface (and not logical) direct object indirect object prepositional object predicate complement of subject predicate complement of object agent of passive particle of phrasal verb complement of catenative relative clause having higher clause as antecedent "guest" having no grammatical role within its tagma Adjunct Functiontags p q t h m place direction time manner or degree modality c r w k b contingency respect comitative benefactive absolute Detailed guidelines for the application of these functional categories is included in ENGLISH FOR THE COMPUTER. NOTES [1] The support of the Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC) is gratefully acknowledged. Project SUSANNE, "Construction of an Analysed Corpus of English", was funded by ESRC award no. R00023 1142, over the period 1988 to 1992. "SUSANNE" stands for "Surface and underlying structural analyses of naturalistic English". I should like to express my warmest thanks to the team who worked on Project SUSANNE, namely Robin Haigh, H<eacute>l<egrave>ne Knight, Tim Willis, and Nancy Glaister. [2] I thank Alvar Elleg<aring>rd for permission to circulate a research resource derived from the work of his group. [3] Ministry of Defence research contract no. D/ER/1/9/4/2062/151(RSRE), "A Speech-Oriented Stochastic Parser". [4] The Brown texts included in the Gothenburg and hence the SUSANNE Corpora are as follows: A01 A09 G01 G09 J01 J09 N01 N09 A02 A10 G02 G10 J02 J10 N02 N10 A03 A11 G03 G11 J03 J12 N03 N11 A04 A12 G04 G12 J04 J17 N04 N12 A05 A13 G05 G13 J05 J21 N05 N13 A06 A14 G06 G17 J06 J22 N06 N14 A07 A19 G07 G18 J07 J23 N07 N15 A08 A20 G08 G22 J08 J24 N08 N18 For details on the source publications from which these texts were sampled, see Francis & Ku<ccaron>era (1989). REFERENCES A. Elleg<aring>rd (1978) The Syntactic Structure of English Texts. Gothenburg Studies in English, 43. W.N. Francis & H. Ku<ccaron>era (1989) Manual of Information to Accompany a Standard Corpus of Present-Day Edited American English, for use with Digital Computers (corrected and revised edition). Department of Linguistics, Brown University, Providence, Rhode Island. R.G. Garside, G.N. Leech, & G.R. Sampson, eds. Analysis of English. Longman. K. Hofland & S. Johansson American English. Longman. (1982) (1987) The Computational Word Frequencies in British and M.P. Marcus & Beatrice Santorini (forthcoming) "Building very large natural language corpora: the Penn Treebank". To appear in N. Ostler, ed., Proceedings of the 1992 Pisa Symposium on European Textual Corpora. R. Quirk, S. Greenbaum, G. Leech, & J. Svartvik (1985) Grammar of the English Language. Longman. A Comprehensive G.R. Sampson (1992) "Probabilistic parsing". In J. Svartvik, ed., Directions in Corpus Linguistics: Proceedings of Nobel Symposium 82, Mouton de Gruyter. G.R. Sampson (forthcoming) "The need for grammatical stocktaking". To appear in N. Ostler, ed., Proceedings of the 1992 Pisa Symposium on European Textual Corpora. SUSANNE.doc