Anne Bradstreet`s “Prologue”

advertisement

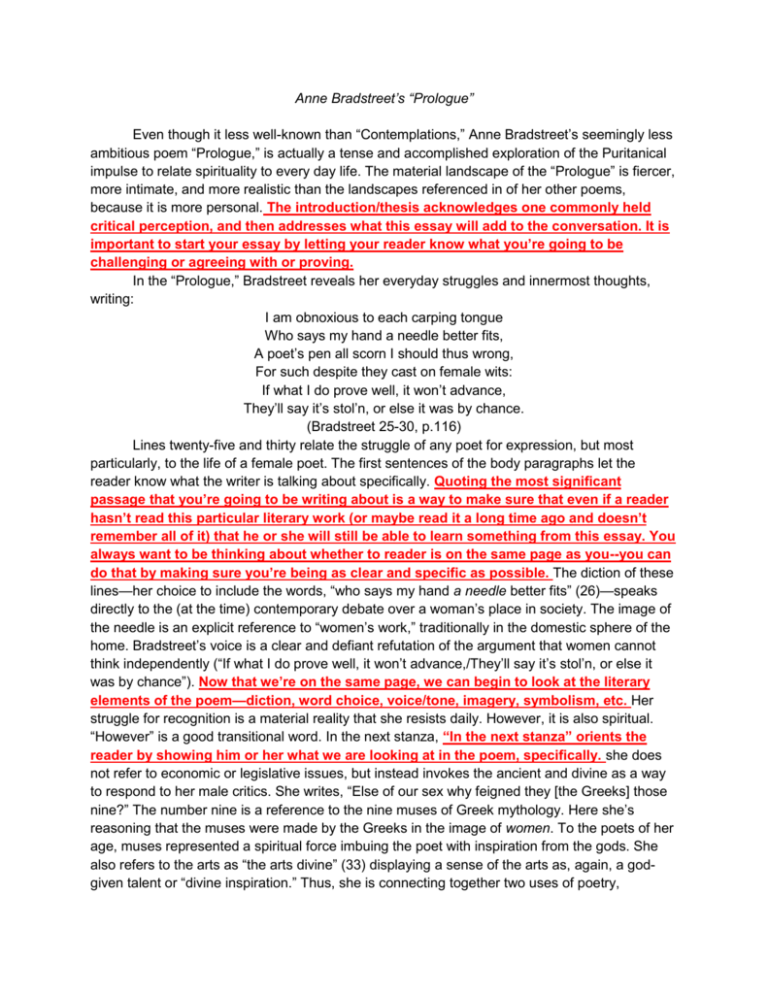

Anne Bradstreet’s “Prologue” Even though it less well-known than “Contemplations,” Anne Bradstreet’s seemingly less ambitious poem “Prologue,” is actually a tense and accomplished exploration of the Puritanical impulse to relate spirituality to every day life. The material landscape of the “Prologue” is fiercer, more intimate, and more realistic than the landscapes referenced in of her other poems, because it is more personal. The introduction/thesis acknowledges one commonly held critical perception, and then addresses what this essay will add to the conversation. It is important to start your essay by letting your reader know what you’re going to be challenging or agreeing with or proving. In the “Prologue,” Bradstreet reveals her everyday struggles and innermost thoughts, writing: I am obnoxious to each carping tongue Who says my hand a needle better fits, A poet’s pen all scorn I should thus wrong, For such despite they cast on female wits: If what I do prove well, it won’t advance, They’ll say it’s stol’n, or else it was by chance. (Bradstreet 25-30, p.116) Lines twenty-five and thirty relate the struggle of any poet for expression, but most particularly, to the life of a female poet. The first sentences of the body paragraphs let the reader know what the writer is talking about specifically. Quoting the most significant passage that you’re going to be writing about is a way to make sure that even if a reader hasn’t read this particular literary work (or maybe read it a long time ago and doesn’t remember all of it) that he or she will still be able to learn something from this essay. You always want to be thinking about whether to reader is on the same page as you--you can do that by making sure you’re being as clear and specific as possible. The diction of these lines—her choice to include the words, “who says my hand a needle better fits” (26)—speaks directly to the (at the time) contemporary debate over a woman’s place in society. The image of the needle is an explicit reference to “women’s work,” traditionally in the domestic sphere of the home. Bradstreet’s voice is a clear and defiant refutation of the argument that women cannot think independently (“If what I do prove well, it won’t advance,/They’ll say it’s stol’n, or else it was by chance”). Now that we’re on the same page, we can begin to look at the literary elements of the poem—diction, word choice, voice/tone, imagery, symbolism, etc. Her struggle for recognition is a material reality that she resists daily. However, it is also spiritual. “However” is a good transitional word. In the next stanza, “In the next stanza” orients the reader by showing him or her what we are looking at in the poem, specifically. she does not refer to economic or legislative issues, but instead invokes the ancient and divine as a way to respond to her male critics. She writes, “Else of our sex why feigned they [the Greeks] those nine?” The number nine is a reference to the nine muses of Greek mythology. Here she’s reasoning that the muses were made by the Greeks in the image of women. To the poets of her age, muses represented a spiritual force imbuing the poet with inspiration from the gods. She also refers to the arts as “the arts divine” (33) displaying a sense of the arts as, again, a godgiven talent or “divine inspiration.” Thus, she is connecting together two uses of poetry, metaphysical expression and social critique. The “Prologue” moves from a worldly, feministmaterialist standpoint to the (she implies) “higher” order of the spiritual (muses, etc.)—not the other way around. These potentially conflicting stances are united in the third stanza. She writes, “Let Greeks be Greeks, and women what they are/Men have precedency and still excel… preeminence in all and each is yours…” (36-41). For Bradstreet, the theme of defiance is acceptable when it comes to critiquing the physical—speaking out against the realities of every-day life—but not acceptable to apply to the spiritual. The first sentence of this paragraph restates the thesis of the paper, but also further complicates and advances it, by adding another idea. In fact, when she begins to reflect on the spiritual, the tone of poem shifts from defiance to acceptance, as if she is now humbled by her own invocation of the metaphysical. In the next stanza, she conveys her awe of her god and the poetry that God inspires, writing, “And oh ye high flown quills that soar the skies/And ever with your prey still catch your praise…” (44-45). These lines present the idea that poetry is not only “God-given,” but that it should be a vehicle of praise for Him as well. The “high flown” quills of poets, “soar the skies,” transcending the physical into the metaphysical world. In this line, her excitement has peaked, and the lofty tone is, as always, brought back to the divine. In order to be vindicated and justified in writing poetry, a poet must “catch [her] praise” from outside sources—for the Puritan, the ultimate critic: God. But, even when invoking God, she does ask for one minor concession: “Yet grant some small acknowledgement of ours” (42). Thus the reader can see the deep-rooted tensions in the poet’s mind between social change or justice, in conflict with the emphasis on mildness, passivity, and acceptance in Puritan society. The last sentence of the paragraph restates the main idea of the essay. Throughout the poem, Bradstreet contrasts poetry as an art (spiritual) and poetry as a vocation (material). For example, though she ends with the “sweeping grace of God,” she also makes direct reference to physical and material gain: “For such despite they cast on female wits: If what I do prove well, it won’t advance/they’ll say it’s stol’n, or else it was by chance” (2730). This is another example from the text (textual evidence). Here she is not referencing or eliciting praise from God, but from critics and other contemporaries, who judge her as a woman (her physical body, not her soul). The “Prologue” conveys the frustration that, while in the eyes of God, Bradstreet may be equal to men, her poetry will never be like that of “a Bartas” (a poet admired by the Puritans), a man, who is allowed to write the poetry of “wars, of captains, and of kings” (1). Much of Anne Bradstreet’s work is comprised of lengthy “contemplations” on the relation of a spiritual god to physical nature. But the “Prologue,” which may initially seem simple and formulaic, is actually imbued with a sense of the tension between the divine and the political and social struggles of every day American life. The final sentence of the essay restates the main idea of the paper, but in a more complete way now that argument has been fleshed out fully for the reader. This is where you connect what you’re saying about your book to the larger themes or “big idea” of the unit (something about life that most of us can relate to). Ask yourself what your reader is going to take away from this essay--what are you getting at? What have you been trying to show us about the work of literature that you’re writing about? How does this work of literature relate to life in general?