Guidelines for Sustainable Intertidal Bait and Seaweed Collection

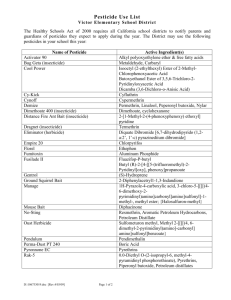

advertisement