Microsoft Word version

advertisement

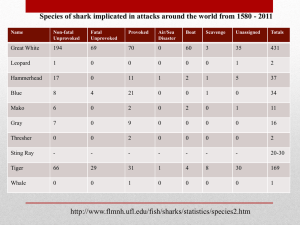

AB 376 Page 1 Date of Hearing: March 22, 2011 ASSEMBLY COMMITTEE ON WATER, PARKS AND WILDLIFE Jared Huffman, Chair AB 376 (Fong and Huffman) – As Amended: March 14, 2011 SUBJECT: Shark Fins SUMMARY: Makes it unlawful for any person to possess, sell or trade a shark fin. Specifically, this bill: 1) Makes it unlawful for any person to possess, sell, offer for sale, trade or distribute a shark fin. 2) Provides an exception to the prohibition on possession of shark fins for any person who holds a permit to possess a shark fin for scientific purposes, and for any person who holds a license or permit to take sharks for recreational or commercial purposes and possesses a shark fin consistent with that license or permit. 3) Defines a shark fin as a raw, dried or otherwise processed detached fin or tail of a shark. 4) Makes legislative findings and declarations regarding the importance of sharks for the ocean ecosystem, and the impacts of the practice and market demand for shark finning. EXISTING LAW: 1) Makes it unlawful to sell, purchase, deliver for commercial purposes, or possess on any commercial fishing vessel any shark fin or shark tail or portion thereof that has been removed from the carcass, with the exception of thresher shark tails and fins whose original shape remains unaltered, which may be possessed on a registered commercial fishing vessel if the corresponding carcass is in possession for each fin and tail (Fish and Game Code § 7704). 2) Authorizes certain species of sharks to be taken or landed with a recreational or commercial fishing license, subject to specified take limits and gear restrictions. The taking of any white shark for recreational or commercial purposes is prohibited. 3) Prohibits the deterioration or waste of fish taken in state waters. 4) Federal law also bans the practice of shark finning in federal waters. FISCAL EFFECT: Unknown COMMENTS: Background: Sharks, of which there are some 400 species worldwide, are top marine predators and live in oceans around the world. The critical importance of sharks to the health, balance and biodiversity of the ocean ecosystem is well recognized in the scientific literature. According to NOAA Fisheries, most sharks are vulnerable to overfishing because they are long-lived, take many years to mature, and only have a few young at a time. Consequently, recovery from overfishing can take years or decades for many shark species. NOAA indicates that since the AB 376 Page 2 mid-1980s, a number of shark populations in the United States have declined, primarily due to overfishing. According to officials at the Monterey Bay Aquarium, over a third of shark species worldwide are currently threatened with extinction. Findings from a few of the more recently published and peer reviewed scientific studies on sharks include the following: A 2003 study of sharks in the Northwest Atlantic showed rapid declines in large coastal and oceanic shark populations, with hammerhead, white and thresher sharks estimated to have declined by 79-89% in just 8 to 15 years, and all recorded species except one by more than 50%. The study noted that despite their vulnerability to overfishing, sharks have been increasingly exploited in recent decades. The authors conclude that the magnitude of the declines suggests several sharks may now be at risk of large-scale extirpation, and that these trends may be reflective of a common global phenomenon. Collapse and Conservation of Shark Populations in the Northwest Atlantic, by Julia Baum and Ransom A. Myers, et al., Science, 2003. Scientists recently completed the first ever census of white sharks off the coast of Central California, published in January 2011. The study estimated only 219 animals, significantly below expected numbers and substantially smaller than populations of other large marine predators. The authors note the susceptibility of shark populations across ocean basins and their role as top predators in ecosystems has resulted in considerable concern about the conservation status of many populations. White sharks in particular are highly susceptible to overexploitation and are listed on the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) red list of most threatened species. The authors emphasized the critical need to protect and monitor great white sharks, especially given genetic data indicating discrete population structure and the importance of sharks for the health of marine systems. A first estimate of white shark, Carcharodon carcharias, abundance off Central California, by Taylor Chapple, et al., Royal Society Biology Letters, 2011. A 2004 study of sharks in the Gulf of Mexico, conducted several years prior to the gulf oil spill, estimated that oceanic whitetip and silky sharks, formerly the most commonly caught shark species, had declined by 99% and 90% respectively. The authors concluded that oceanic whitetips are ecologically extinct in the Gulf. They stressed that these precipitous declines may be reflective of a general phenomenon for oceanic sharks, and that such significant altering of entire assemblages of large predators may have a considerable impact on the pelagic ecosystem. Shifting Baselines and the Decline of Pelagic Sharks in the Gulf of Mexico, by Julia Baum and Ransom Myers, Ecology Letters, 2004. Another 2003 study estimated that large predatory fish biomass, including sharks, in the oceans today is only about 10% of pre-industrial levels. The authors concluded that declines in large predators in coastal regions have extended throughout the global ocean, with potentially serious consequences for ecosystems. Rapid Worldwide Depletion of Predatory Fish Communities, by Ransom Myers and Boris Worm, Nature, 2003. Finally, a 2006 study that examined shark biomass in the shark fin trade concluded there is significant underreporting of shark fin harvest, as the shark biomass in the fin trade was three to four times higher than reported shark catch figures. The study focused primarily on blue sharks. While the authors indicated further research was needed before the findings of the study could be used to draw conclusions about other shark species, they emphasized that the large difference AB 376 Page 3 between trade-derived estimates of exploitation and the catch estimates reported added to growing concerns about the overexploitation of sharks. Demand for shark fin is largely believed to be the primary driver behind overfishing of sharks and recent shark population declines. According to an article in the New York Times, every year up to 73 million sharks are killed for their fins, primarily to make shark fin soup. Support Arguments: Supporters note that sharks are critical to the health and balance of the ocean ecosystem and their extinction would be devastating to the biodiversity of the oceans of the world. Demand for shark fin drives overfishing of sharks and has contributed significantly to recent shark population declines. Some species have been depleted by as much as 90% and over a third of shark species are threatened with extinction. Supporters assert that currently there are no recognized sustainable shark fisheries, and note that sharks are particularly susceptible to overfishing due to low reproductive rates and their role as top predators in the marine food chain. Supporters also assert that current state and federal laws have been ineffective in curbing the practice of shark finning as long as trade in fins is allowed to continue in response to market demand. While recognizing that shark finning has been important to Chinese culture for centuries, supporters assert collapse of ocean ecosystems must take precedence over cultural culinary heritage, noting also that many governments and businesses in the Pacific region have recognized the urgency to save sharks and implemented progressive protection measures. Recreational fishing organizations assert that shark finning is inconsistent with sustainable fishing practices. Some supporters also emphasize the cruelty of shark finning, which often involves cutting off the fins and tails of sharks and throwing the fish back in the ocean alive where they are likely to die a slow death. Finally, some supporters note the high level of mercury in shark meat makes them unhealthy to eat. Opposition Arguments: Although the committee has not received any formal opposition letters to this bill, news articles have quoted some individuals and businesses within the Chinese American community who assert that banning the possession or sale of shark fins will deprive Chinese Americans of the ability to enjoy the long valued cultural tradition and heritage of shark fin soup. According to the Los Angeles Times, shark fin soup was a luxury item in traditional Chinese culture, once reserved for emperors and kings, with a bowl of soup today costing as much as $100. The Times indicates the growing middle class in China has created new market demand for the soup which is also popular among Chinese Americans. According to the San Francisco Chronicle, shark fin soup has been a traditional Chinese dish going back to the Han Dynasty some 1,800 years ago. The Chronicle reports that dried shark fin in San Francisco's Chinatown today sells for $178 to $500 a pound, and shark fin soup typically costs $250 to $500 for ten people. It should be noted that legislation to ban shark finning has recently been proposed in China by a member of the Chinese parliament. Legislation banning shark finning has also been enacted in the state of Hawaii and is pending before the state legislatures of Oregon and Washington. Some opponents of this bill have also suggested that shark finning should be regulated through greater enforcement rather than by banning trade of shark fins. Supporters of this bill note in rebuttal to that argument that current state and federal laws have proven ineffective in stemming the overfishing of sharks which is driven by the market demand and lucrative trade in shark fins. Most shark fins in California are imported from other countries where California has little or no ability to police or control finning practices and no way of knowing whether shark fins in those AB 376 Page 4 countries are sustainably harvested. Supporters also assert a ban on importation of listed species would likely be unenforceable due to the difficulty in determining with accuracy the species of the shark after the fins have been dried and processed. Finally, even for species that are not yet listed as threatened or endangered, supporters assert maintaining a sustainable shark fishery is extremely difficult if not impossible due to the life history of sharks as apex predators with low reproductive rates that make them particularly susceptible to overfishing and rapid depletion. REGISTERED SUPPORT / OPPOSITION: Support Action for Animals Animal Place Aquarium of the Bay Asian Americans for Community Involvement Asian Pacific American Ocean Harmony Alliance Body Glove International California Academy of Sciences California Association of Zoos and Aquariums California Coastal Commission California Coastkeeper Alliance California League of Conservation Voters COARE Coastside Fishing Club Defenders of Wildlife Environment California Heal the Bay Monterey Bay Aquarium Natural Resources Defense Council Oceana Pacific Environment Reef Check California San Francisco Baykeeper Santa Cruz County Board of Supervisors Sea Stewards Shark Savers The Bay Institute The Humane Society of the United States The Sierra Club The Sportfishing Conservancy United Anglers of Southern California Wild Coast/Costasalvaje WildAid Opposition None on file Analysis Prepared by: Diane Colborn / W., P. & W. / (916) 319-2096