Reward-Processing Deficits in Active but not Remitted Depression

advertisement

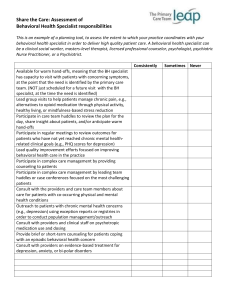

UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS AT CHICAGO Department of Psychiatry Fifth Annual Research Forum – Extravaganza 2014 POSTER TITLE Reward-Processing Deficits in Active but not Remitted Depression DISEASE/KEY WORDS: Depression, behavioral activation system, reward-processing AUTHORS: Sophie R DelDonno1, Annie L Weldon2, Alessandra M Passarotti1, Brian J Mickey3, Patrick J Pruitt3, Natania A Crane1, Laura Gabriel12, Wendy Yau2, Kortni K Meyers2, David T Hsu3, Stephen F Taylor2, Mary M Heitzeg2, Stewart Shankman5, Jon-Kar Zubieta234, Scott A Langenecker12 1 Department of Psychiatry, University of Illinois at Chicago 2Department of Psychiatry, University of Michigan 3Molecular & Behavioral Neuroscience Institute, University of Michigan 4Department of Radiology, University of Michigan 5 Department of Psychology, University of Illinois at Chicago RESEARCH MENTOR: Scott A Langenecker12 MENTEE CATEGORY: student BACKGROUND: Anhedonia is one of the core symptoms of major depressive disorder and leads to impaired reward processing. Individuals with depression have trouble learning reward contingencies and adjusting their behavior to earn rewards, and are overly sensitive to punishment. Low positive affect and high negative affect may underlie these rewardprocessing deficits. The present study investigated reward-learning impairments in actively depressed (aMDD; in Study 1) and remitted depressed (rMDD; in Study 2) participants, as well as the influences of behavioral activation (positive affect) and behavioral inhibition (negative affect). We asked whether reward learning and/or affective personality traits may be risk factors for depression or relapse. METHODS: Study 1 participants (20 aMDD, 14 HC) and Study 2 participants (33 rMDD, 17 HC) completed a modified Monetary Incentive Delay Task (mMIDT) and the Behavioral Inhibition System/Behavioral Activation System (BIS/BAS) scale. The mMIDT was titrated to participants’ individual performance in a practice run to ideally elicit 50% 80% accuracy. Titration adapts the task to the participant’s advantage so they can win a majority of the trials while also standardizing the task by removing the effect of each participant’s individual psychomotor ability. UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS AT CHICAGO Department of Psychiatry RESULTS: In Study 1, a repeated measures ANOVA revealed that aMDD participants won significantly less money than HCs and that aMDD participants lose money over time. A multiple regression model showed that aMDD performance was predicted by BAS Reward-Responsiveness subscale scores. We ran identical analyses in Study 2 and found that rMDD and HC did not differ on amount of money won in the mMIDT, and both groups won more money as the task went on. In Study 2 the BIS/BAS scales did not predict performance. CONCLUSIONS: Despite titration aimed at removing psychomotor effects of illness, actively depressed participants exhibited reduced reward pursuit. Trait reward-responsiveness predicted this outcome. Individuals with remitted depression performed identically to healthy participants, suggesting that impaired reward-seeking may be a state effect of illness. BIS and BAS scores were restricted in Study 2, perhaps preventing us from seeing a relationship. Further research should address whether these results are due to participant age, age of onset, number of episodes, or scanner interference.