The Artificial in Harmony with Natural Process: Eco

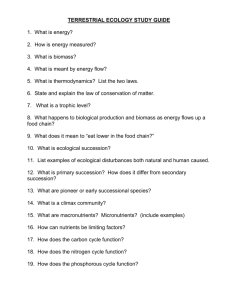

advertisement

Eco-literacy, Ethics, and Aesthetics in Natural Design: The Artificial as an Expression of Appropriate Participation in Natural Process Daniel C. Wahl, BSc. (Hons.), MSc., Centre for the Study of Natural Design, University of Dundee Abstract: The design approach advocated in this paper makes one fundamental assumption: the appropriateness of any design is the extent to which it meets human needs and integrates sustainably into the life-supporting natural processes of the planetary biosphere. The author suggests that an aesthetic of health, based on ecological literacy, can inform the evaluation of the qualitative fit between design and its environment. Eco-literacy - a detailed understanding of nature as a complex, interacting, creative process in which humanity participates – results in a shift in perception toward an ecological ethics and aesthetics of participation that considers cultural, social and ecological, as well as economic value. As perception becomes informed by ecological literacy it can begin to bridge the dichotomy between the artificial and the natural, as well as between humanity and nature. Ecological literacy creates awareness of the fact that a disproportionate amount of the artificial environments, infrastructures, artefacts and processes that have been created since the Industrial Revolution are harmful to natural process and decrease the dynamic stability and health of the biosphere. The diversity of approaches within the Natural Design Movement affirms that we can create artefacts and processes that are expressions of appropriate participation in natural process. Sustainable and responsible design is a creative possibility and an ecological necessity. Ecological literacy emphasizes that humanity is an integral participant in natural processes, which are fundamentally unpredictable and uncontrollable. Local actions can have far reaching global effects. Interconnectedness results in cause and effect relationships within complex systems that are not linear but circular, multi-causal, and often time delayed. This awareness confronts us with the need to assume responsibility for the outcomes of our actions and furthermore changes the perception of humanity’s relationship to nature. The aim shifts from control and manipulation to appropriate participation. There is therefore an important ethical and aesthetic dimension to ecologically literate design. The Natural Design Movement shares an ecological worldview. The movement unites diverse disciplines ranging from ecological design, industrial and urban ecology, sustainable architecture and bioregional planning to ecological economics, eco-literate education and green politics. Furthermore it considers the philosophical, sociological and psychological implications of the ecological worldview. Design in the 21st century will be grounded in eco-literacy and aspire toward community-based designs that are adapted to the specific conditions of a particular place and culture. This paper concludes that long-term sustainable design has to integrate into natural processes as the basis for planetary and human health. There is an ecological dimension of ethics suggesting ecological imperatives that transcend the relativistic moralizing of purely socio-philosophical ethics. Eco-literacy creates awareness of these ecological imperatives that will help designers to create responsible and sustainable artefacts, processes and organizations. Designing the artificial as an expression of appropriate participation in natural process has to be based on ecological literacy and supported by the emerging aesthetics of health, also referred to as the ecological aesthetics of sustainability and the aesthetics of complex dynamic systems. Keywords: aesthetics, complexity, diversity, eco-literacy, ethics, health, interconnectedness, Natural Design Movement, participation, uncontrollability, unpredictability, salutogenesis, sustainability 1 I) Introduction Human designs are goal-directed responses to a certain way of perceiving reality. At the same time, a design once created also co-creates reality and thereby influences future design decisions based on that reality. Being ecologically literate - to be aware of the complex web of interactions and relationships that underlies the dynamics of ecosystems and the biosphere as a whole - changes how nature and our role within its processes is perceived. Such a change in perception has important ethical and aesthetic implications. To clarify: when I refer to ‘nature’ in this paper, I intend to describe a physical, chemical, biological, ecological and conscious process which contains culture in all its diversity of belief and opinion. Arguably ‘nature’ is an abstract noun and its meaning is culturally and socially influenced, but I understand nature as the larger all containing process that enables us to have our misunderstandings in the first place. While in such a view of nature nothing falls without this process, it nevertheless remains possible for designed artefacts and processes to either support or disrupt the overall evolution of natural process. The assumption is made that the process from which the ‘subsystems’ biosphere and humanity emerged is evolving higher levels of complexity, diversity, and interdependence or symbiosis. The dynamic stability, or health of the biosphere and its sub-systems depends on the continuation of this evolutionary tendency. Furthermore, I wish to clarify at the outset that the term ‘system’, as it is used in the following pages, can be equated with the words ‘process’ or ‘holon’ (for an explanation of the concept ‘holon’ see Koestler, 1970 & Wilber, 1996). My intent is not to reinforce mechanistic metaphors where systems describe wholes that are purely the sum of their parts and their study is aimed at increasing our ability to better predict and control these systems. The term system is used here in the context of complexity. Complex dynamic systems or processes defy control and prediction. The characteristics of the whole are understood as emergent properties that depend on the complex dynamics of interaction and relationship among the parts. A ‘complex dynamic system’ is always recognized to be more than simply the sum of its parts. All complex dynamic systems are in a participatory relationship with the larger processes that contain them. This paper introduces the collective term ‘Natural Design Movement’ to unite the diverse disciplines engaged in the creation of a sustainable future. It should be explicit at the outset, that the intention is not to set up and define yet another design subdivision and specialization. It is not a critique or alternative to, but an expansion of the existing ecological design approaches, as it also considers consciousness, ethics and aesthetics. The Natural Design Movement hopes to bring together the diverse fields of design activity, which aim to integrate all design into natural process as the basis of planetary and human health. All designs of human artefacts, institutions and processes that aim to meet human needs in a sustainable way, thereby contributing to humanity’s appropriate participation in natural process, can be considered expressions of the Natural Design Movement. The movement unites all the efforts within design theory and practice that are engaged in providing the philosophical, ethical, aesthetic and practical basis for sustainable design in the 21 st Century. Appropriate participation in natural process requires ecological literacy. Such knowledge of the complex dynamic of interdependencies and interactions that sustain life on earth has the potential of triggering a shift in perception and therefore in aesthetic experience. Awareness of the actual and 2 the potential ecological effects of his/her actions confronts the designer with the important question of an ethical basis for design. Human inventions and capabilities (for both good and ill – as always) are increasing at a furious pace. Managing the torrent in a way that avoids serious insult to society and the rest of nature is proving to be difficult. As awareness of the effects of our actions sharpens, we must now ask the uncomfortable question: can art, craft or design be truly worthwhile and wonderful if it engenders an environmental mess and ruined lives elsewhere? (Baldwin, 1998) II) Design as an Interdisciplinary Integrator and Facilitator In proposing that “the proper study of [hu]mankind is the science of design, not only as a professional component of a technical education but as a core discipline for every liberally educated person” (Simon, 1996, p.138) Herbert Simon concurs with Ranulph Glanville`s assertion that ‘science is a special branch of design and not design a special branch of science.’ Glanville suggests the ultimate expansion of the concept of design when he argues that ‘the process in which we draw up and shape things could be called design. Human action is design’ (Glanville, 1997 translated from Jonas 2001). Design should not be considered one of many specialized fields of human endeavour; rather, design can be understood as the integrative process or activity that connects human actions and attitudes to their material and cultural expression in form of artefacts, institutions, and processes. As Homo faber, the human maker, our material actions and mental constructs shape our world. “Every act of knowing brings forth a world. … All doing is knowing, and all knowing is doing. …We have only the world we bring forth with others…” (Maturana & Varela, 1992, p.25 & p.249). The concept of design, in its broadest possible sense can help us to integrate the remarkable wealth of specialized knowledge and skill that rests within humanity. I will argue that in order to do so wisely humanity has to become ecologically literate and reconsider ethics and aesthetics. Since Herbert Simon, in 1969, first suggested design to be “the science of the artificial” (Simon, 1996, p.134), the concept of design has clearly undergone a progressive expansion. In the same year, Ian L. McHarg published Design with Nature, the first attempt of a theory and methodology for design within the limits of the biosphere. In McHarg’s insightful future forecasting scenario, “The Naturalists”(McHarg, 1969, pp.117), he describes a human society, which has evolved to a level of ecological consciousness that has led the society to regard the entire biosphere as an altruistic system in which they themselves and their designs need to participate appropriately. McHarg describes the Naturalists’ co-operation-focussed, rather than competition-focussed understanding of the natural world as follows: Every organism occupies a niche in an ecosystem and engages in cooperative arrangements with the other organisms sustaining the biosphere. In any case this involves a concession of some part of the individual freedom towards the survival and evolution of the biosphere” (McHarg, 1969, p. 121). 3 Like Simon, McHarg saw the potential of design to act as an interdisciplinary integrator or interface. They both agreed that design needed to include and be informed by natural science but also to extend beyond it. According to McHarg, the extension of design beyond science included social, cultural, aesthetic, as well as ethical consideration of interaction and interdependence. He understood that our fundamental value systems and ethics critically influence our design decisions and inform our aesthetic judgement. McHarg suggested that to contribute to the continued evolution of culture and consciousness, as expressions of the noosphere, human designs had to first and foremost fit into the dynamic processes of the planetary biosphere. He introduced a strongly ecological, social, and ethical stance into design theory and the evaluation of a given design or artefact. III) Lessons of Complexity and Ecological Literacy Truly, we are now in a new world where the old certainties are melting away and we have to learn to think and act differently. We have to interact with these uncertain processes, which affect our health, our food, our weather, our standard of living. The challenge that we now face is how to live in a creative, unpredictable, magical world without destroying it by inappropriate actions and attitudes that come from outmoded attitudes of control and prediction (Goodwin, 2001). The increase in awareness regarding the pivotal and formative role that design plays in human affairs and in shaping the relationship between humanity and nature went hand in hand with a growing awareness of the fundamentally interconnected and dynamic nature of the complex world we inhabit. In 1972 Donella and Dennis Meadows published their report to the Club of Rome, entitled Limits to Growth. It was the first clear warning to humanity about the fact that we are living on a planet with finite resources and a limited capacity to absorb pollutants (Meadows & Meadows, 1972). In the 1980s, the German biochemist and systems scientist Frederic Vester designed a travelling exhibition entitled “Unsere Welt – ein vernetztes System” (Our world – an interconnected system) to raise awareness of the profound implications that insights from bio-cybernetics and the resulting ecological understanding had for human decision making at all scales of magnitude and societal contexts (Vester, 1983). As the effects of climate change and environmental degradation are becoming more and more apparent, awareness is increasing about humanity’s participatory relationship of mutual dependence within the complex dynamic system called the biosphere. The call for an ecological ethic as the basis for sustainable design has many diverse expressions throughout global and local culture. In 1999, Munich Reinsurance, the largest reinsurance company in the world, published an alarming report that demonstrated the exponential increase in the number and severity of natural catastrophes that occurred during the course of the 20th century. The report left no doubt that climate change and environmental degradation was due to human activity and called for an immediate response in all sectors of society (Münchner Rück, 1999). 4 It is a fact to be lamented that since Simon, in 1969, proposed that the theory and curriculum of design should act as “a complement to the natural science curriculum” (Simon, 1996, p. 136) rather than a replacement, and McHarg called for an ecological basis for all design decisions, basic ecological understanding and crucial insights from complexity theory and Earth System Science are still lacking from the curricula of most design schools. In order to reach adaptively advantageous design decisions and initiate the continuous and long-term path of learning that is sustainability, our designs decisions will need to be informed by ecological, economic, social and cultural considerations that are based on eco-literacy. Insights from systems theory, ecology, bio-cybernetics and complexity theory (for an introduction see: Capra, 1996, 2002; Goodwin, 1994, 1999, 2000; Gunderson and Holling 2002; Maturana & Varela, 1992; Lovelock, 2000; Reason & Goodwin, 1999, Wheatly, 1999) provide a scientific underpinning for a theory of design resulting in designs that fit the wider process environment. Such a design theory would be informed by an understanding of natural process, without being limited by the traditional bounds of natural science. The research described by these authors demonstrates that from within science there is a strong call for what Frederic Vester called “vernetzdes Denken” (Vester, 1999). This dynamic, ‘joined-up thinking’ extends into all human ways of knowing. It relates and integrates the diverse insights gained from specialization and is fundamentally interdisciplinary. The holistic sciences study interactions and relationships in the behaviour of complex dynamic systems. The focus is on the underlying patterns and emergent properties. These sciences carry three important lessons beyond the bounds of traditional science. These lessons are: i) we are living in a fundamentally interconnected world where local actions can have global repercussions, ii) in such a complex and dynamic web of changing interactions and time delayed, multicausal relationships it is of limited use and can have dangerous effects to isolate individual and simplistic, linear cause and effect relationships, iii) the behaviour of complex systems is fundamentally unpredictable and uncontrollable beyond a very limited time period and scale. Design theory is not blind to these lessons any longer. Design and science are beginning to accept the limits that fundamental interconnectedness, unpredictability and uncontrollability pose to our knowledge about the world. Wolfgang Jonas argues for a “new role for design: more modest and more arrogant” in response to being faced with “the paradox situation of increasing manipulative power through science and technology and, at the same time, decreasing prognostic control of its social consequences” (Jonas, 2003). I would also include the ecological consequences in this statement. Design is becoming ‘more arrogant’, as we expand the concept of design to encompass all human decision-making and action and thereby recognize its creative power and responsibility; and ‘more modest’, in the sense that we abandon the arrogance of believing that human ingenuity empowered by science and technology, will provide designers with the tools to fix even the gravest 5 mistakes. Lost cultures and lost ecosystems are gone for ever, plutonium remains carcinogenic for 40,000 years, lost topsoil takes millennia to regenerate, and changes in the atmospheric composition affect climate patterns for millions of years. Jonas suggests that: “Instead of expanding the islands of apparent scientific rationality (which frequently turn out to be unsafe), we [need to] cross the border from knowing to not-knowing. And on this side of the border we can determine (with scientific underpinning!) the areas of safe nonpredictability” (Jonas, 2003). This statement could be regarded as the essence of the precautionary principle that should guide science, design and politics alike. If we cannot predict the outcome of a certain action, but the possibility remains that it may have potentially disastrous side effects, we should refrain from that action, or, at the very least, experiment on a scale and with the appropriate measures of protection that would keep negative effects to an absolute minimum. It is time to drop old habits of indiscriminate and worldwide application of what is technically possible and economically marketable! Jonas’ emphasis is on methods of risk management in situations where we cannot know, but nevertheless do have to act. An important aspect of ecological literacy is to make the fundamental unpredictability and uncontrollability of natural process and all other complex systems more intelligible. Eco-literacy will not always provide us with statistically significant predictions of the outcomes of our actions. Its lessons take us beyond the certainty of rational analysis and linear cause and effect into the chaotic and complex dynamics of natural systems. Islands of safe unpredictability are built by considering the appropriate spatial and temporal scale for our actions and through ‘verneztes Denken’ that integrates what we do know in the humble awareness of what we can’t know. IV) Ecological Literacy as a Prerequisite for Responsible and Sustainable Design The three lessons of complexity theory, previously mentioned, form part of what David Orr has called “ecological literacy” (Orr, 1992). Orr identified the lack of ecological literacy in society as one of the key factors in the degradation of the environment and the continued propagation of thoroughly unsustainable design methodology and design decisions. The environmental educator Anthony Cortese and David Orr, both advocate that eco-literacy should be taught alongside basic writing skills, mathematics and physical education from an early age onward. It is a prerequisite for responsible decision making in a fundamentally interconnected world. Cortese writes: Because all members of society consume resources and produce pollution and waste, it is essential that all of us understand the importance of the environment to our existence and quality of life and that we have the knowledge, tools, and sense of responsibility to carry out our daily lives and professions in ways that minimise our impact on the environment (Cortese, 1992). Instilling basic eco-literacy in every citizen of the global village lies at the core of the sustainability challenge. Responsibility can no longer be deferred to government or industry alone; it has to be assumed by each and every individual. Everyday, civil society has to make choices that can either increase or decrease the ability of future generations to lead a humane and healthy life. Design 6 professionals and educators hold a pivotal position in the propagation of eco-literacy through the creation of designs that are based on ecologically literate decision making processes but also embody eco-literacy through the materials they employ and the way they integrate benignly or beneficially into the natural processes that maintain the health of our environment and therefore human health. In The Nature of Design, Orr puts forward a strong case for the crucial role of design in guiding humanity towards a sustainable future. Like the architect, William McDonough, and the biologist and designer, John Todd, Orr suggests that we are at the brink of a cultural shift, more rapid and more global than the Industrial Revolution. They argue we are beginning to witness an ecological design revolution that through its material expression and corresponding awareness will redefine the relationship between humanity and nature (see McDonough & Braungart, 2002; Todd & Todd, 1993; Orr, 2002). Orr proposes “ecological design is a large concept that joins science and the practical arts with ethics, politics and economics” (Orr, 2002, p.4). An understanding of the three lessons of complexity - fundamental connectedness, unpredictability, uncontrollability – is transforming the scientific worldview and promoting an ecological worldview. This ecological worldview will critically inform the design of the 21st Century. As design begins to face up to its crucial role in creating the world of tomorrow and designers assume their own responsibility in this process of co-creation with nature, all designers will need to become ecologically literate. Eco-literacy results in an awareness of the basic dependence of all biological and ecological systems on their underlying physical and material systems. Science, culture and society - Luhmann’s autopoietic social systems (see e.g. Luhmann, 1992, 1997) - in turn depend for their existence on the continuing autopoiesis at the level of biological and ecological systems (Maturana & Varela, 1992). As eating and breathing biological organisms, all humans, and all their mental constructs and ways of perceiving and “being in the world” (Heidegger, 1978) depend on underlying biological and physical process. What Herbert Simon referred to as system hierarchy (see Simon, 1996, pp.182) describes a linear, either/or (rational) logic based understanding of the dependence of biological on physical, and rational (conscious) systems on biological systems. Arthur Koestler’s notion of the system holarchy (Koestler, 1970) better anticipated the current understanding of emergence and complexity. It expresses a form of circular, both/and as well as either/or (non-dual) logic in describing the mutual interdependence of biological, physical and conscious systems within an undivided, dynamically transforming whole. This non-dualistic logic that underlies such concepts as complex dynamic systems and their holarchical relationships can be schooled through increasing ecological literacy. Fritjof Capra argues, “the major problems of our time … are all different facets of one single crisis, which is essentially a crisis of perception.” He suggests a shift towards an “ecological awareness” that “recognizes the fundamental interdependence of all phenomena and the embeddedness of individuals and society in the cyclical process of nature” (Capra, 1994). It is this necessary shift in perception, based on ecological literacy that Gregory Bateson referred to in Steps to Ecology of Mind. Bateson argued that our concept of ‘self’ is a very limited one that needs to be expanded and that we have to learn to identify our ‘selves’ with the wider ecological 7 relationships that characterize and define us as humans (Bateson, 1972). He recognized the rigid classification of self/world, humanity/nature, and mind/matter into mutually exclusive categories as resulting from an adherence to dualistic/rationalistic either/or logic. The shift in perception described by Bateson has profound implications for ethics and aesthetics. It leads toward an ecological or environmental ethic that lies at the heart of the ecological design revolution and informs a new ecological aesthetic, as well as the ecological worldview. Ecologically literate design reflects the suggestions by Simon and McHarg that designed artefacts have to establish the appropriate fit between themselves and their environment. Design is not so much about making things as about how to make things that fit gracefully over long periods of time in a particular ecological, social, and cultural context (Orr, 2002, p.27). V) Ecological Ethics in Design While important lessons about an environmental ethic can be learned from many of the world’s traditional cultures, the conservation ecologist Aldo Leopold provided the first modern formulation of an ecological and environmental ethic within the Western cultural context. Leopold proposed that: “A thing is right when it tends to preserve the integrity, stability, and beauty of the biotic community; it is wrong when it does otherwise” (Leopold, 1966). Leopold realized that ethics is essentially not only a philosophical but also an ecological ‘process’. Ethics ultimately concerns the relationship between the individual and the collective in aiming to define appropriate participation. Moralizing, that masquerades as ethics, can quickly be identified when the ecological component of ethics is understood. Leopold argued that “the extension of ethics to include man’s relationship to the environment” was an “evolutionary possibility” but an “ecological necessity.” He wrote, “an ethic ecologically, is a limitation of freedom of action in the struggle for existence. An ethic, philosophically, is a differentiation of social from antisocial conduct.” Leopold continues, “these are two definitions of one thing which has its origin in the tendency of interdependent individuals and groups to evolve modes of cooperation” (Aldo Leopold, 1949, quoted in McHarg, 1964). Ethics guide modes of participation through cooperation and symbiosis. Ethics in its wider context is not only about guiding human interactions within exclusively human communities. A solely philosophical ethic, considered only within the social and cultural dimension, is often abused for moralizing from the position of a single cultural and societal context and set of values. The wider function of ethics - its ecological imperatives - extends beyond anthropocentric concerns. According to the Australian eco-designer and design theorist, Tony Fry, designers can no longer absolve themselves from their ethical responsibilities, by deferring such responsibilities to their clients. Beyond a basic code of professional conduct and professional due diligence, the ethical implications of any design need to be discussed during early stages of the design process, and they need to be considered not only within an anthropocentric - often economically dominated - context, but aim to preserve ecological, social, and cultural value and expand ethical considerations to a more bio- 8 centric view. Fry proposes: “an ethics of now crucially needs to confront our anthropocentric being as a structurally unethical condition” (Fry, 2004). Understanding the ecological lessons of interconnectedness and mutual dependence triggers a biocentric ethic, which found an early expression in the work of Leopold, McHarg and many others. McHarg insisted that humanity has to learn the “prime ecological lesson of interdependence” and understand that all humans are “linked as living organisms to all living and all preceding life.” He was convinced that through understanding our interdependence “with the micro-organisms of the soil” and “the diatoms of the sea” humanity would learn that when it destroys nature it destroys itself and when it restores nature it restores itself (McHarg, 1963). A concise introduction to various approaches to a guiding environmental ethic can also be found in Bernd Löbach, “Theoretischer Hintergrund ökologieorientierten Designs” (Theoretical Background of Ecologically Oriented Design, see Löbach, 1995). He traces the ethical implications of various positions from egocentrism, via anthropocentrism and biocentrism to cosmocentrism. In Löbach’s opinion all designers need to confront these various ethical positions and their corresponding value systems, since such a confrontation provides the basis for orienting their own actions and allows them to assume and defend responsible positions through their own arguments and creative actions (Löbach, 1995). Dialogue about environmental ethics is an integral part of the ecological literacy curriculum and so is the study of the complex dynamics of natural systems from a scientific perspective. We need to understand the relationships between diversity, dynamic stability and health of natural ecosystems. Diverse and richly connected systems are more able to adapt to drastic disturbances through natural disasters or human forcing of the system. An increased awareness of the extent of our dependence on the ecological, hydrological, atmospheric and geological processes of the biosphere would clearly support a more biocentric and holistic position and demonstrate the limited moral and mental horizon of the anthropocentric position. Eco-literacy is the basis of an informed ecological ethic. Ethic based on eco-literacy can guide appropriate participation. Ethics are about the appropriate integration and creative participation of the individual in the collective. Ethics are about conviviality at the level of the family, the community, society, and the extended community of life. Ecological literacy results in an awareness of conscious participation that integrates the aware subject into the natural, social and cultural processes of the world. Such participatory awareness emphasizes the need to assume responsibility for one’s actions. Ecological literacy makes us aware of the effects of individual actions on global and local processes and it persuades us of the urgent necessity to act responsibly. Understanding the ecological component of ethics and identifying oneself, as a living organism, with the community of life profoundly changes our perception of our self and the world. As such, ecological literacy has not only ethical but also aesthetic implications. VI) Ecological Literacy and the Emerging Ecological Aesthetics In a recent article entitled, Reconciling Eco-Ethics and Aesthetics in Design, Jack Elliott reiterates some of the points discussed above. Like Bateson, Capra, McHarg, Leopold, and others, Elliott is also 9 convinced that “in order for real change to occur in human-nature relationships, all living things must be brought into the orbit of ethical consideration. This requires human empathy to extend beyond our corporal shell. The ethical domain must be reframed from the anthropocentric to the biocentric”. Elliot points out that: “empathy is an important form of knowing, especially as it pertains to the aesthetic subject” (Elliott, 2004, p.5). An expansion of empathy towards the perceived ‘object’ will change aesthetic experience profoundly. Expanding our empathy towards the living world, when combined with ecological literacy, results in ecological consciousness and solves what Capra referred to as the crisis of perception. This change in perception, or paradigm shift, lies at the beginning of the path towards sustainability. Our perception and self-world conception changes at every stage of the extension of empathy beyond ego, family, community, society, culture, and species. Ecological consciousness is reached as empathy extends towards the community of life, the biosphere or even the entire cosmos. The founder of integral psychology, Ken Wilber, describes this progressive expansion of empathy as the path of individual development as well as a map of consciousness itself (see Wilber, 1996, 2001). A discussion of Wilber’s work within the context of the role of design as interdisciplinary facilitator and integrator would prove fruitful, but leads beyond the scope of this paper. At this point, it should simply be noted that there are rigorous and complex models of the development of the human psyche and the evolution of consciousness that suggest such an expansion of the empathic horizon may be part of the evolution of consciousness in general. Our perception of the world is critically influenced by our empathy for the world. The awareness of interdependence with the natural world that is mediated by ecological literacy forces us to expand our empathy towards the community of life as a whole, the collective future of which is so closely linked with our own. How we perceive, especially our relationship with the world, is the determinant of our aesthetic experience. Nicolas Bouriaud speaks of a “relational aesthetics” (Bouriaud, 1998) and Jale Erzen equates this term with ecological aesthetics, since ecology is about interdependence and relationship and such exchanges and relations always depend on mutual perception and thus on aesthetics. Erzen argues “aesthetics and ecology can be said to be complementary and interdependent” (Erzen, 2004, p.22). The German artist Herman Prigann sees the root of the environmental problems in our “inability to understand the dialogue between nature and culture that defines their relationship through mutual dependence” (Prigann, 2004, p111). In Prigann’s opinion the undeniable environmental problems we face demand “a new capacity for aesthetic judgement” (Prigann, 2004, p. 75). Prigann emphasizes “it is not ecology that needs an aesthetic treatment, instead the aesthetic follows ecological insights. Nature does not need an aesthetic domestication” (Prigann, 2004, p.180). Prigann formulates the shift in perception mediated by this ecological aesthetic insightfully: An ecological aesthetic would be a perspective on our environment and society as well as the ensuing theory and practice. This perspective would annul current, standard contradictions such as nature – art // nature – technology // nature – civilization // nature – culture and 10 proceed towards an insight of the principle of dialogue in and towards everything (Prigann, 2004, p.180). Echoing Gegory Bateson’s search for ‘the pattern that connects’, Prigann suggests “aesthetics is the recognition of the pattern that connects everything.” He believes that “through attentiveness to pattern, that connection in everything – the universal togetherness – evolves an aesthetic perspective of perception”. He calls for an ecologically based aesthetic that “emphasises the demand to direct attentiveness of our perception towards the living, the living pattern of nature” (Prigann, 2004, p.181). Prigann clearly understands the importance of ecological literacy and he also understands that such literacy would not be solely based within a scientific paradigm. To the contrary it would gain part of its strength through the intuitive and creative dimensions of aesthetic practice. The landscape architect Udo Weilacher also believes that “a general environmental ethic is urgently required.” He highlights that an ecological aesthetic “would tacitly accept that man as a living organism is part of nature but as a cultural and reasoning being he has his autonomy and thus has to take full responsibility for his actions” (Weilacher, 2004, pp.116). Weilacher’s comment reinforces the link between ecological literacy and ethical responsibility by embracing the paradoxical situation that as biological organisms humans are dependent on natural processes, but as cultural and rational beings humanity has emancipated itself enough to be fully responsible for its actions. VII) An Ecological Aesthetics of Participation The cultural historian, Hildegard Kurt, argues that we are in search of a new “aesthetics of sustainability” that expresses itself on the one hand through “forms of the less,” but at the same time through “nature-friendly opulence” (Kurt, 2004, p.238). Kurt emphasizes that such a new aesthetic will “grant a constructive productive force to sensual awareness and aesthetic competence, and use this force for designing life-sustaining futures” (Kurt, 2004, p.238). Kurt also stresses the important role that a participatory awareness plays in the development of such an aesthetic of sustainability. She thereby clearly supports the eco-literacy-participation-responsibility-ethics-aesthetics to sustainable design link this paper is hoping to communicate. Since the path of learning about appropriate participation that embodies sustainability has to be walked by the vast majority of the human population in order to bring about the desired result of a sustainable future, I agree with Kurt in that “an aesthetics of sustainability will always be an aesthetics of participation as well – or will have to become one” (Kurt, 2004, p.239). She identifies another important point: When the discourse about the aesthetics of sustainability articulates a new sensitivity to the fact that there is effective creative knowledge beyond technical-instrumental reason, that offers viable alternatives, then the question of the relationship between sustainability and art can no longer be ignored. But it is at precisely this point that difficulties in understanding presently arise (Kurt, 2004, p. 239). 11 We have thus identified two important prerequisites of a culture of sustainability: Firstly, it has to be based on participation. Secondly, the main barrier that inhibits full participation is our currently culturally dominant worldview that is based on ‘technical-instrumental reason’. While this way of knowing, when employed as a tool rather than an ideology has proved extremely useful, its dogmatic and ideological influence on science, technology, economics and design has suppressed an ethical and aesthetical contribution to the dialogue of an emerging culture since the scientific revolution and increasingly since the Industrial Revolution. Aesthetics play such an important role because aesthetic questions direct awareness towards perception itself rather than detached observation. Aesthetics can raise awareness of the role that our knowledge plays in the way we experience and conceptualise the world. Aesthetics is about perception, which emerges out of the encounter of direct sensory experience and mental patterns of thought, concepts and basic assumptions (see also Bortoft, 1996). Instrumental reason, a clear linear cause and effect logic based on dualistic, mutually exclusive opposites, has helped in the creation of the now advanced version of the Newtonian map of a mechanistic ‘billiard ball’ universe - a map that still proves useful in many daily challenges, but has its limits despite, and to some extent because of, the manipulative power it provides. A common cultural problem is to confuse the map with the territory. In a culture that classifies the world through quantification and statistical significance, where economic gain is the main measure of success, qualitative aspects and relationships can easily be neglected. Our environmental, social and cultural problems are largely the result of a neglect of qualitative social and ecological value in favour of purely quantitative economic value. The vastly oversimplified map that reductionistic and mechanistic science has painted of the world does not sufficiently describe the complexity and interdependence within the system in which we participate. It overemphasizes the role of competition in evolution through its focus on separate individuals. At the level of the whole, nature is held together by cooperation and symbiosis. VIII) Towards a Design guided by an Aesthetics of Health and Salutogenesis Health is, both, an emergent property of and the pattern that connects complex dynamic systems. The holistic sciences are tentatively sketching a map of the world based on the metaphor of complex dynamic systems and the concept of emergent order out of chaos. This map is a fuzzy map that acknowledges limits to what is knowable, to prediction and to control. Rather than focusing on isolating single cause and effect relationships, this map tries to make multi-causal, non-local, timedelayed relationships of mutual interdependence more intelligible. Complex dynamic systems are their own cause and effect in the creative tension between polarities. Mutually exclusive opposites do not exist in this map. The paradox of both/and is not avoided but embraced (see also Reason & Goodwin, 1999). An aesthetic of health sensitises us to health generating interactions at the level of the whole of nature. It may help us to trace out the map of relationships and interactions that lead to appropriate participation in salutogenesis at the level of the whole. The aesthetics of health will guide us towards actions and designs that increase the health of the planetary biosphere. The goal shifts from control 12 and manipulation to appropriate participation. Interconnectedness sets the context for co-operation rather than competition. This emerging map of the world as a complex dynamic system has its origin in natural science and the ecological realities of natural process, but in acknowledging the limits of instrumental technical reason and emphasising the dynamic and participatory nature of perception and existence, the map is clearly acknowledging the important contribution that non-scientific ways of knowing can make to the dialogue about appropriate participation and thus sustainability. The emerging map is not an exclusively scientific map, nevertheless it acknowledges the importance of ecological literacy in guiding appropriate decision making, based on the assumption that humanity does want the evolution of culture and consciousness to continue and therefore needs to integrate appropriately into natural process. In many ways, the emerging map is also an aesthetic map, if we accept Timothy Collins definition of aesthetics as “the philosophy of ideas and physical perception that informs experience” (Collins, 2004, p. 170). The aesthetics of complex dynamic systems are rooted in valuing diversity, interconnectedness, and cooperative exchanges or symbiosis as the basis for the dynamic stability of the system. Such dynamic stability could also be referred to as resilience or health. As such, the process of integrating the artificial through appropriate participation into natural process is informed by an aesthetic of health. The guiding principle of design becomes salutogenesis (Baxter, 2003), the creation of healthy, dynamically resilient systems. Design begins to act in full recognition of the fundamental unity and interdependence of nature and culture. Once again, McHarg provided an early formulation of the same thought. He wrote: “Because this whole system is in fact one system, only divided by men’s minds and by the myopia which is called education, there is another simple term which synthesizes the degree to which an invention is creative and accomplishes a creative fitting. And this is the presence of health”(McHarg, 1970). McHarg’s definition of ‘design with nature’ was a practice of design that increases interconnectedness, diversity, fitness, complexity and health throughout the system as a whole. To McHarg this system is nature and culture. Culture is the most rapidly adaptable means to re-establish a creative fit between humanity and nature. Biological adaptations to a changing environment take a lot longer to evolve than cultural adaptations! McHarg foresaw the shift from a culture that is intent on controling and exploiting nature, to a culture of appropriate participation in the restoration of the earth and the health of nature (see McHarg, 1996). Such a culture of appropriate participation is now emerging. In the long term a culture of sustainability will evolve, unless humanity takes the other route into continued mass extinction that will sooner or later include our own species. An aesthetic of health can aid in choosing the former instead of the latter option. The American artist Timothy Collins describes the new emergent aesthetics that are sensitive to the relationships between diversity, complexity and health insightfully: Health is a term for the aesthetic understanding of complexity. There is a thread connecting biodiversity, cultural diversity and economic diversity. This is the metaphorical understanding of the health of a complex dynamic system. This is an idea that few of us will ever be able to conceptualise in detail, but I think that many of us are beginning to sense in terms of aesthetic pattern. The relative health of a landscape, an organism, the health of a system, even the 13 health of a technological construct, is a material problem of diverse complexity. … The perception of health is a relative term, it requires intimate knowledge over a period of time and a caring critical attention. In turn, a lack of health can be described in terms of emergent dominant systems that mitigate the constraint of diversity. Diversity is healthy expression and perception is an integrative, dialogic concept. This concept departs from the autonomous object of classical aesthetics, defined as unity, regularity, simplicity, proportion, balance, measure and definiteness. Within the aesthetic perception of diversity lies systemic relationship, dynamism, complexity, symbiosis, contradiction to measurement and indefinite and procreative vitality. I believe that an aesthetic of diversity is emergent but not yet cogent. It is a theoretical view with an experiential basis that must be identified and pursued by many. It will not be captured in terms of a singular theory, a definite practice or primary authorship (Collins, 2004, p. 172). IX) Summary and Conclusion Where does all of this lead us? Do such theoretical, ethical and philosophical considerations really belong to 21st century design? In my opinion, they form the basis of it. Ian McHarg once wrote “there is nothing as practical as a good theory”(McHarg & Steiner, 1998) and Wolfgang Jonas recently suggested, “there is nothing more theoretical than a good practice”(Jonas 2003). In general, it is a good habit to embrace paradoxes and seeming contradictions as an indication of good holistic thinking rather than something to be avoided. They indicate a more comprehensive and integrative understanding and invite us to go deeper. Donella Meadows proposed that our ability to comprehend and participate in a complex system increases significantly once we can move between paradigms (Meadows, 1997). Coming to terms with paradoxes provides the basis for an informed design dialogue that aims for approximate appropriate participation in natural process, in one word: sustainability. This paper proposed the concept of the Natural Design Movement as a collective term to bring together the diverse attempts within design theory and practice that are aiming to create human artefacts and processes as expressions of humanity’s appropriate participation in natural process. In other words, Natural Design is not a new design specialisation; it unites all the currents of 21 st Century design, which are contributing to the transformation of human society towards sustainable practices. The Natural Design Movement encompasses such diverse fields as ecological product-, process- and institutional design, sustainable architecture, community-, urban- and bioregional planning, industrial ecology, and ecological engineering, but also political systems of governance, ecological economics, education for sustainability, renewable resource based technologies and energy production, as well as aspects of bionics, eco-technology, and green chemistry. When human designs are understood in their broadest sense as all goal directed human actions, as all artefacts, processes, and institutions of culture, then Natural Design concerns all of these, which are intending to meet human needs while integrating benignly or beneficially into natural process. The Natural Design Movement is informed by an understanding of complex dynamic systems and ecological literacy. Awareness of the fundamentally interdependent relationship between 14 humanity and nature and an understanding of the basic ecological life-support systems of the planetary biosphere can provide the cognitive basis for comprehending humanity’s critical role as a responsible participant in natural process. I proposed that ecological literacy confronts with the need to take responsibility for our actions and therefore with ethical questions about how to participate appropriately. Ethics was identified as not only pertaining to a philosophical-social-cultural expression, but as having an ecological basis which allows us to distinguish relativistic social moralizing from a truly co-operative, symbiotic and synergetic ethics of contributing to the health of the community of life. An increase in ecological literacy and a confrontation with the ecological as well as the social dimension of ethics can result in an extension of empathy beyond the limits of the individual self, the social or cultural group identity and even the biological species. Such increased awareness can result in a profound shift in perception towards a form of ecological consciousness through which the world is perceived with an ecological aesthetic. This ecological worldview motivates the Natural Design Movement. I argued that since perception concerns the definition of self and world and the resulting awareness of relationships and interactions, aesthetics, like ethics, has an intrinsically ecological dimension. An ecological aesthetic is an integrative and participatory perception of relationships and interactions between artificial and natural process. It leads to an informed dialogue between culture and nature. An ecological aesthetics places artefacts into a dynamic context rather than understanding them as something separate from natural process. Everything is understood in terms of where and how it emerged into material existence, how it relates to the physical, biological and conscious processes around it, and how it will ultimately be reabsorbed by the wider natural process. As such, an ecological aesthetic informs our understanding of metamorphosis, dynamic transformation and change. To recognize that reality in its physical, ecological and social dimension is ultimately more complex than our models, or maps, could ever be and to accept the uncontrollability and unpredictability of such complexity are the first steps of the humble process of learning how to participate appropriately in that complexity. This process of continuous learning lies at the heart of sustainability. There is a basic tendency within complex dynamic processes, especially when living beings are concerned, to evolve towards higher levels of interconnectedness and thus cooperative interaction or symbiosis. The health of complex dynamic systems seems to be intimately linked with their diversity and the dynamic stability that results from intricately networked webs of cooperative as well as competitive interactions. An ecologically informed aesthetic perception of complex dynamic systems combined with joined-up and holistic thinking trains the ability to empathically perceive the dynamic relationships between all the diverse agents. Such an understanding of process and relationship informs intuitively and empirically about the health of the system. The perception, preservation and restoration of the condition of systemic health, or dynamic stability, are the underlying strategies of all sustainable designs. Salutogenesis, or health generation at the scale of local and global ecosystems and social systems has to become the priority of design in 15 the 21st Century if we want to create a sustainable global civilization through diverse, locally adapted cultures of co-operation. The design strategies of the future will aim to balance cooperative and competitive interactions within a system in such a way that the overall resilience of the system is increased. This requires a maintenance and restoration of diversity within the system (see Gunderson & Holling, 2002). Design will have to learn from and mimic nature’s economy of zero waste, renewable resource use and energy sources. An ecological ethic, together with an aesthetic of health will assure that designs are considered within their ecological, cultural and social context, and are benign or health generating rather than disruptive to natural process. The creative challenge and opportunity for design is to meet human needs within the limits and possibilities set by the overall process that maintains the health and diversity of the biosphere. Such designing is critically supported by ecological literacy and guided by an ecological ethics and the emerging aesthetics of health, diversity and complexity. 16 References: Baldwin, James (1998) “The Ultimate Swiss Omni Knife”, Whole Earth Review; Winter 1998 Bateson, Gregory (1972) Steps to Ecology of Mind” Intertext (New Edit. 2000, University of Chicago Press) Baxter, Seaton (2003) personal comment, Prof. Seaton Baxter is the head of the Centre for the Study of Natural Design at the University of Dundee, Scotland; see also: Antonovsky, Anton (1979) Health, Stress and Coping, Jossey-Bass Publishers Bortoft, Henry (1996) The Wholeness of Nature – A Goethean Way of Science, Floris Books Bourriaud, Nicolas (2002) Relational Aesthetics, Dijon Capra, Fritjof (1994) “Systems Theory and the New Paradigm” in Key Concepts in Critical Theory: Ecology, Carolyn Merchant edit., Humanity Books Capra, Fritjof (1996) The Web of Life – A New Synthesis of Mind and Matter, Harper Collins Capra, Fritjof (2002) The Hidden Connections – A Science for Sustainable Living, Harper Collins Collins, Timothy (2004) “Towards an aesthetics of diversity” in Ecological Aesthetics – Art in Environmental Design: Theory and Practice, Prigann & Strelow edit., Birkhäuser, pp. 170-180 Cortese, Anthony (1992) “Education for an Environmentally Sustainable Future”, Environmental Science and Technology 26:6 1992: 1108 - 1114 Elliott, Jack (2004) “Reconciling Eco-Ethics & Aesthetics in Design” in Design Philosophy Journal, www.desphilosophy.com Erzen, Jale (2004) “Ecology, art, ecological aesthetics” in Ecological Aesthetics – Art in Environmental Design: Theory and Practice, Prigann & Strelow edit., Birkhäuser, pp.22-50 Fry, Tony (2004) “The Voice of Sustainment: The Dialectic” in Design Philosophy Journal, www.desphilosophy.com Glanville, Ranulph (1997) “Nicht wir führen die Konversation, die Konversation führt uns!”, in Zirkuläre Positionen: Konstruktivismus als praktische Theorie, Westdeutscher Verlag Goodwin, Brian (1994) How the Leopard changed its spots – The Evolution of Complexity, Orion Publishing Ltd. Goodwin, Brian (1999) “Reclaiming a Life of Quality”, Journal of Consciousness Studies, No. 6 11-12, pp. 229 – 235 Goodwin, Brian (2000) “From Control to Participation via a Science of Qualities”, Revision Vol. 21 No.4 Goodwin, Brian (2001) “Holistic Education in Science” S.E.A.L. Conference Proceedings Gunderson, L. & Holling, C.S. eds. (2002) Panarchy – Understanding Transformation in Human and Natural Systems, Island Press Heidegger, Martin (1978) Being and Time, Blackwell Publishers Jonas, Wolfgang (2001) “Design – es gibt nichts Theoretischeres als eine gute Praxis” Symposium IFG Ulm 21. – 23. September 2001, http://home.snafu.de/jonasw/index.html Jonas, Wolfgang (2003) “Mind the gap! On knowing and not knowing in design” European Academy of Design Conference Paper 2003, see http://home.snafu.de/jonasw/JONAS4-62.html Koestler, Arthur (1970) Ghost in the Machine, Pan Books Kurt, Hildegard (2004) “Aesthetics of Sustainability” in Ecological Aesthetics – Art in Environmental Design: Theory and Practice, Prigann & Strelow edit., Birkhäuser, pp. 238-242 Leopold, Aldo (1966) A Sand County Almanac: With Essays on Conservation from Round River, Ballentine Books Löbach Bernd (1995) “Theoretischer Hintergrund ökologieorientierten Designs”, in Design und Ökologie, Bernd Löbach & Ernst Albrecht Fiedler edits., Designbuch Verlag Lovelock, James (2000) Gaia – The Practical Science of Planetary Medicine, Gaia Books Luhmann, Niklas (1992) Die Wissenschaft der Gesellschaft, Suhrkamp Luhmann, Niklas (1997) Die Gesellschaft der Gesellschaft (Band 1&2), Suhrkamp Maturana, Humberto R. & Varela, Francisco J. (1992) The Tree of Knowledge – The Biological Roots of Human Understanding, Shambhala Boston & London Meadows, Donella & Meadows, Dennis (1972) Limits to Growth: A Report for the Club of Rome’s Project on the Predicaments of Mankind, Universe Publ. 17 Meadows, Donella (1997) “Places to Intervene in a System”, Whole Earth Review, Winter 1997 McDonough, William & Braungart, Michael (2002) Cradle to Cradle – Remaking the Way We Make Things, North Point Press McHarg, Ian L. (1963) “Man and the Environment”, in To Heal the Earth – Selected Writings of Ian L. McHarg, Edit. Ian L. McHarg and Frederick R. Steiner, Island Press, 1998 McHarg, Ian L. (1968) “Values, Process and Form”, in To Heal the Earth – Selected Writings of Ian L. McHarg, Edit. Ian L. McHarg and Frederick R. Steiner, Island Press, 1998 McHarg, Ian L. (1969) Design with Nature, Doubleday/Natural History Press McHarg, Ian L. (1970) “Architecture in an Ecological View of the World” in To Heal the Earth – Selected Writings of Ian L. McHarg, Edit. Ian L. McHarg and Frederick R. Steiner, Island Press, 1998 McHarg, Ian L. (1996) A Quest for Life – An Autobiography, Wiley and Sons McHarg, Ian L. (1997) “Ecology and Design”, in To Heal the Earth – Selected Writings of Ian L. McHarg, Edit. Ian L. McHarg and Frederick R. Steiner, Island Press, 1998 McHarg, Ian L. & Steiner, Frederick R. (1998) To Heal the Earth – Selected Writings of Ian L. McHarg, Island Press Münchner Rück (1999) Naturkatastrophen in Deutschland. Schadenerfahrungen und Schadenpotentiale, Münchener Rückversicherungs-Gesellschaft Orr, David W. (1992) Ecoliteracy – Education and the Transition to a Postmodern World, State University of New York Press Orr, David W. (2002) The Nature of Design – Ecology, Culture, and Human Intention, Oxford University Press Prigann, Herman (2004) “Art and science – perspectives and ways of an ecological aesthetic”, in Ecological Aesthetics – Art in Environmental Design: Theory and Practice, Birkhäuser, pp. 180-188 Prigann, Herman (2004) “Prologue – thoughts about nature” in Ecological Aesthetics – Art in Environmental Design: Theory and Practice, Birkhäuser, pp. 74 - 90 Reason, Peter & Goodwin, Brian (1999) Towards a Science of Qualities in Organisations, Concepts and Transformation 4:3, pp. 282-317 Simon, Herbert A. (1996) The Science of the Artificial (3rd Edition), MIT Press (The 1st edition was published in 1969) Todd, Nancy Jack & Todd, John (1993) From Eco-Cities to Living Machines – Principles of Ecological Design, North Atlantic Books Vester, Frederic (1983) Unsere Welt – ein vernetztes System, Deutscher Taschenbuch Verlag, 11. Auflage 2002 Vester, Frederic (1999) Die Kunst vernetzt zu denken – Ideen und Werkzeuge für einen Umgang mit Komplexität, Der Neue Bericht an den Club of Rome, dtv, 4. Auflage 2004 Weilacher, Udo (2004) “Ecological Aesthetics in landscape architecture today?” in Ecological Aesthetics – Art in Environmental Design: Theory and Practice, Birkhäuser, pp.116-128 Wheatly, Margaret J. (1999) Leadership and the New Science – Discovering Order in a Chaotic World, Berrett-Koehler Publications Wilber, Ken (1996) A Brief History of Everything, Shambala Boston & London Wilber, Ken (2001) A Theory of Everything – An Integral view for Business, Politics, Science and Spirituality, Gateway About the author: Daniel C. Wahl studied Biological Sciences at the University of Edinburgh and the University of California, Santa Cruz. He graduated with Honours in Zoology in 1996. In 2002 he completed his Masters in Holistic Science at Schumacher College and the Department of Environmental Science of the University of Plymouth. He is currently writing up his PhD at the Centre for the Study of Natural Design of the University of Dundee, Scotland. Postal address: Daniel C. Wahl The Centre for the Study of Natural Design Duncan of Jordanstone College of Art and Design University of Dundee Dundee DD1 4HT Scotland, UK Electronic mail: d.c.wahl@dundee.ac.uk 18