The General Synod and Europe

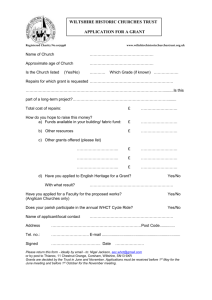

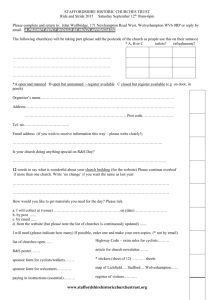

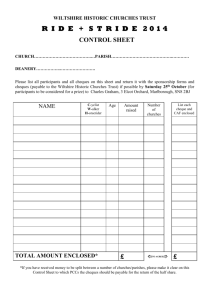

advertisement