Hear Today - Gone Tomorrow?: Communicating Negative

advertisement

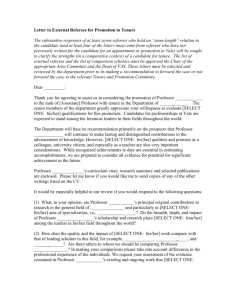

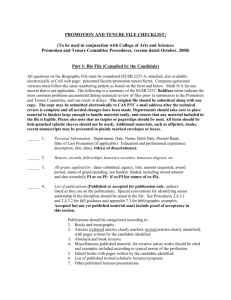

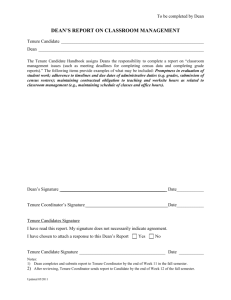

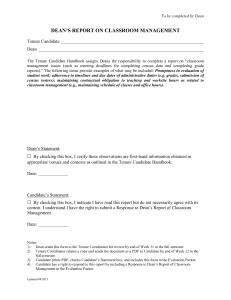

#17 HEAR TODAY - GONE TOMORROW?: COMMUNICATING NEGATIVE INFORMATION ABOUT EMPLOYEES AND STUDENTS June 16-19, 1996 Stephen J. Hirschfeld McKenna & Cuneo San Francisco, California I. INTRODUCTION At one time or another it is likely that most university administrators and professors have been asked to provide an employment or tenure reference for a former colleague. Most gladly comply, whether for reasons of professional courtesy or in recognition of the fact that they will likely require a similar favor in the future. While this routine exchange usually does not generate litigation, it can -- and increasingly does. Many corporate employers, facing increasing legal claims brought by unsuccessful job applicants, have adopted a "name, rank, and serial number" reference policy in an attempt to head off possible litigation. Whether this actually reduces exposure to litigation is debatable, especially in light of an the emerging theory of "compelled selfdisclosure." More importantly, for higher education institutions such a policy is simply not practical. What goes around, comes around. Over time, a "name, rank, and serial number" policy will significantly hamper an institution's ability to recruit and evaluate its own candidates as word spreads in the tight-knit academic community that an institution is unwilling to provide informative references. This is a serious problem, because colleagues' evaluations of a candidate's teaching and research skills, collegiality, and academic integrity are essential to evaluating faculty candidates. Furthermore, a noreference policy may also serve to reduce the number of quality applicants applying to the institution -- applicants undoubtedly take into consideration the prospects of a positive, informative reference when deciding where to apply. This is especially true for adjunct, student, or other temporary teachers who may plan to use the job as a stepping stone to a full-time position at another university. Complicating matters are the unique challenges the academic environment presents with respect to references. In higher education, the free flow and informal exchange of ideas among colleagues is generally encouraged. But informal exchanges create problems when the subject discussed is a job or tenure candidate. Another unique challenge is the often frequent dichotomy between the job or tenure reference and information in the faculty member's personnel file. Faculty members value a community of interest, and peer reviewers (of papers and grant proposals) have a tendency to give overly-positive reviews. If a subsequent job or tenure reference is less than favorable, the candidate may question the truthfulness of the reference. Finally, reference policies of colleges and universities can become the subject of intense scrutiny, whether it be the scrutiny of a candidate denied tenure or even that of the press under state statutes granting #17 public access to state university presidential searches. This scrutiny may lead to litigation. Although references admittedly provide significant exposure to liability, informative references are indispensable. By understanding the reference-related liability exposures and by implementing a well-planned reference policy, institutions can limit their liability in this area without resorting to a name, rank and serial number approach to references. I. PROVIDING EMPLOYMENT REFERENCES -- THE LEGAL PROBLEMS Reference-related claims filed by the unsuccessful job or tenure candidate include defamation, invasion of privacy, misrepresentation (either negligent or intentional), interference with prospective employment, and "blacklisting." From the hiring institution or third party (for example, students or colleagues) the potential claims include misrepresentation, negligent referral, and negligent hiring. A. Defamation In order to establish defamation, an employee must show that a false statement was made to a prospective employer or tenure committee, and that the statement would likely harm the employee's reputation or deter other persons from wanting to hire or grant tenure to the candidate.1/ Defamation can be oral ("slander") or written ("libel"). It typically arises when the former employer or colleague provides an unfavorable, false reference or an incomplete or vague reference. However, under the emerging theory of "compelled self-publication" it may even arise from the employer's refusal to give a reference where the employee himself discloses negative information to a prospective employer.2/ Under this theory, the employee candidate argues that he or she was "compelled" -- usually upon the prospective employer's inquiry -- to reveal the allegedly false reasons for his or her separation from previous employment. Although this tort is not recognized in all jurisdictions its use is growing. Truth, the most obvious defense, is often difficult to establish, especially when the reasons for an employee's departure are multiple or are in dispute. Furthermore, tenure references tend to be based on opinion and not grounded in easily-verifiable facts. And while mere opinion will not support a claim of defamation, often the line between fact and opinion is blurred, particularly in statements made regarding the quality of a faculty 1 / 2 Restatement (Second) of Torts § 573 (1977). / See Lewis v. Equitable Life Assurance Society, 389 N.W.2d 876 (Minn. 1986). #17 member's teaching or research. If key facts are in dispute, the school will not be able to easily dismiss the claim. Another defense available to reference-providers has been dubbed the qualified privilege. Nearly all jurisdictions in the United States provide a qualified privilege to a reference-provider who in good faith provided what turned to be a false or incomplete reference. In order to establish the privilege, the reference must: (1) be made in the good faith belief of its truthfulness; (2) serve a legitimate business need; (3) be limited to serving that business need; (4) be made on the proper occasion; and (5) be published only to parties with a legitimate interest in the communication.3/ The defense is not available to an employer or colleague who knew the information was false or incomplete or acted with reckless disregard with respect to the truth or falsity, or who distributed the reference to those without a legitimate need to know its contents.4/ In the case of Olsson v. Indiana University Board of Trustees,5/ Indiana University successfully asserted the defense of qualified immunity at a very early stage of a defamation case, precisely because it was able to establish that the professor reviewing the candidate had a good-faith basis for his unfavorable reference. A student teacher had claimed that she had been defamed when a university faculty member provided an unfavorable reference letter in response to a request from the interviewing school's superintendent. The faculty member had described the student teacher as "marginal" and did not recommend her for employment. After being denied employment, the student teacher sued IU claiming defamation. The university was able to establish that the professor had a good-faith belief in the marginality of the student teacher's skills, in part because of the significant amount of time the professor had spent observing the candidate's student teaching and also because of the supporting documentation in the files. In short, whether the information was true or false was not critical -- the real issue was whether the professor had a good faith basis for his evaluation. Because he did, IU was able to get the case dismissed. A third defense available to reference-providers is consent; that is, the employee consents to the release of employment information.6/ Most courts require that the consent 3 / Restatement (Second) of Torts § 595 (1977). 4 / See, e.g., Kelly v. General Telephone Co., 136 Cal. App. 3d 278, 285 (1982); Deaile v. General Telephone Co., 40 Cal. App. 3d 841, 846 (1974). 5 / 571 N.E.2d 585 (Ind. App. 1991). 6 / See, e.g., Litman v. Massachusetts Mut. Life Ins. Co., 739 F.2d 1549, 1560 (11th Cir. 1984); Turner v. Halliburton Co., 240 Kan. 1, 10-11 (1986); Patane v. Broadmoor Hotel, 708 P.2d 473, 476 (Colo. Ct. App. 1985). #17 be in writing. Although a written consent form need not be lengthy to be effective, at a minimum it should include language authorizing the release and full disclosure to prospective employers of any information the school may have concerning the individual's employment. A clause to the effect that the employee releases the school, its employees, and anyone acting on its behalf from any and all claims, liability and/or damage of any nature which may result from furnishing the information requested is usually sufficient. The employee should be required to sign and date the form. Note, however, that a consent form will usually not protect the school from liability for intentional misrepresentations; most courts consider that to protect such an employer would violate public policy. A. Other Claims By Employees Other less common claims arising from employment references include: 1. Invasion of Privacy -- this claim is typically based upon one the following theories: (1) the institution unreasonably placed the former employee in a "false light" before the public; or (2) the school unreasonably disclosed private information about the employee. 1. Misrepresentation -- this claim requires that the job or tenure candidate establish: (1) the institution knew that the information would be needed for an important purpose (i.e., obtaining employment or tenure); (2) the person to whom the information is given intended to act upon it; (3) the individual was harmed as a result of the information being provided; and (4) there was a relationship between the parties such that the candidate had the right to rely on the reference-provider and the referenceprovider had a duty to provide a reference with care (negligent misrepresentation); or the reference-provider knew the reference was false (intentional misrepresentation).7/ 2. "Blacklisting" -- this statute-based claim arises when the former employer intentionally misrepresents information about a former employee to prevent the former employee from getting a job or gaining tenure.8/ Several states have made the offense a misdemeanor, punishable by fines and/or imprisonment. Examples of such states include California and Texas.9/ Other states merely impose civil liability. 7 / See, e.g., Marshall v. Brown, 141 Cal. App. 3d 408 (1983). / See, e.g., Cal. Lab. Code § 1050. 8 9 / See, e.g., Cal. Lab. Code § 1050; Tex. Lab. Code § 52.031(c). #17 States also vary as to whether the statement must be written in order to impose liability, or whether an oral statement will suffice. 1. Interference with Prospective Employment -- This claim is very similar to blacklisting, but is based on principles constructed by the courts rather than on statutory guidelines.10/ Thus, even though the state may not have a "blacklisting" statute, actions that would render the institution liable under such a statute may subject the school to liability for interference with prospective employment. This claim arises when an institution intentionally interferes with a former employee's right to employment by giving false information to prospective employers and when such conduct results in a loss of an employment opportunity. A. 1. Claims By The Hiring Institution and/or Third Parties Negligent Referral Not only may the employee sue the reference-provider, but so too may the hiring institution or even a third party under a theory of "negligent referral."11/ The theory is premised on the employer's affirmative duty to warn future employers about any traits which would pose a danger to anyone who might foreseeably come in contact with the employee. By not giving information, an employer can be contributing to a future injury by the hiring institution or a student or employee. 1. Intentional Misrepresentation This claim is similar to negligent misrepresentation, but requires actual knowledge of the dangerous traits. Fraud can be asserted against one who does not have a duty to warn -- for example, colleagues of the former employee. Although fraud claims arising from employment references are rare, they do exist. They typically involve "misleading halftruths" rather than affirmative lies. In the recent case of Randi W. 10 / See, e.g., Scholtes v. Signal Delivery Serv., 548 F.Supp. 487 (W.D. Ark. 1982) (applying Arkansas law). 11 / See, e.g., Greenfield v. Spectrum Inv. Corp., 174 Cal. App. 3d 111, 118-20 (1985); Bates v. Doria, 150 Ill. App. 3d 1025, 1030-31 (1986); Henley v. Prince George's County, 305 Md. 320, 330 (1986). #17 v. Livingston Union School Dist.,12/ a girl molested by a school vice principal brought a successful action against several referenceproviders for, among other things, fraud, alleging that the reference-providers had written letters recommending the vice principal without revealing his history of sexual molestations. The reviewers were fellow teachers, and had not limited their statements to the vice principal's teaching or administrative abilities, but had also commented upon his personal qualities. The appellate court found that the reviewers had reason to know of the vice-principal's problems and that their failure to warn, especially in light of their commendation of the candidate's integrity, was actionable fraud. I. OBTAINING EMPLOYMENT REFERENCES A. Negligent Hiring If an employer fails to check references, or did not adequately check them, it may be liable to a third party under a theory of "negligent hiring" if the employee causes injury to that third party. Under this theory, an employer has an affirmative duty to exercise reasonable care in selecting employees so as to ensure the safety of third parties who may come in contact with the employee. The claim is available to all third parties who might reasonably come in contact with the employee; in the context of a college or university, this would likely include administrative personnel, an employee's colleagues, and students. Most jurisdictions recognize this claim, and have applied it for a variety of torts, including assault, theft, and sexual harassment.13/ The degree to which colleges and universities scrutinize references depends to some extent upon the position sought. A college or university may not scrutinize as thoroughly the references of a part-time or adjunct faculty candidate as they do a candidate for a full-time position. Furthermore, there may be circumstances when it is simply not possible to check references as 12 / 41 Cal. App. 4th 400, review granted, 96 Daily Journal D.A.R. 3301 (1996). 13 / See, e.g., North Houston Pole Line Corp. v. McAllister, 667 S.W. 2d 829 (Tex. Ct. App. 1983) (damages sought for assault based on negligent hiring theory); Hogan v. Forsyth Country Club Co., 79 N.C. App. 483 (1986) (damages sought for sexual harassment based on negligent hiring theory). #17 thoroughly as an institution might desire. An unexpected absence either before or during the school year may require a quick and less than thorough search outside the university for someone to fill the slot. At the very least it is necessary to conduct a thorough review of all references listed on the candidate's resume or otherwise identified by the candidate in order to avoid a claim of negligent hiring. If the candidate does not volunteer certain references, ask for the names of current and/or past administrators or supervisors and obtain the employee's written consent to contact them. I. TENURE REFERENCES The tenure process is an extremely detailed evaluation of a candidate's skills. It involves a host of recommendations and evaluations from various sources. Tenure references present many of the same liability issues as do employment references, with a few added concerns. Administrators should expect that a candidate will carefully scrutinize the reasons for denial of tenure. In the process, accompanying references may be subject to review. Furthermore, at this stage in a faculty member's career, references may require a quite subjective discussion of the candidate's abilities and may provide greater exposure to legal claims. A. Confidentiality and Subjectivity Tenure candidates solicit references from colleagues, deans, and students. Many of the individuals solicited will not be accustomed to providing reference letters and may not be aware of the potential legal and practical consequences of doing so. Universities can no longer guarantee that peer review materials will be confidential. Increasingly, courts have been finding that tenure review materials are discoverable in litigation, particularly in cases involving discrimination.14/ For example, when Northwestern University was recently faced with a sex discrimination claim by a professor denied tenure, the court found that the professor was entitled to both the identities of her peer reviewers and evaluations they submitted.15/ 14 / See EEOC v. University of Pennsylvania, 493 U.S. 182 (1990). 15 / Schneider v. Northwestern University, 151 F.R.D. 319 (N.D. Ill. 1993). #17 A. Qualified Privilege As with employment references, courts have granted tenure reference-providers a privilege with respect to allegedly defamatory information. Although some jurisdictions grant an absolute privilege to comments made during the tenure review process under a theory that the candidate consents to the statements by virtue of having submitted to the tenure process, others grant only a conditional privilege; that is, the statements must be with a good-faith belief in their truthfulness. In any case, in order to utilize the privilege, reference letters must be submitted in connection with the tenure process in order to be privileged. A Colby College student successfully asserted this conditional privilege in Lester v. Powers.16/ In that case, a college professor brought a libel claim against a former student who had written a letter concerning the professor in connection with tenure review. The student asserted that the letter was written in response to the tenure committee's solicitation and also that it expressed opinion, not fact. Although the student submitted the letter after the deadline provided for such letter, which in many cases would have made the student ineligible to claim the privilege, in this case, the court agreed that the conditional privilege should attach and dismissed the lawsuit. I. A. DEVELOPING A REFERENCE POLICY Providing Employment References 1. Require that all requests for references be made in writing on collegiate or business stationary. 1. Where possible, channel all requests for references to the personnel or human resources department or an appropriate college administrator, and let all who might be approached for references know about that procedure. This is probably easier to do with staff than with faculty, but it is important for both groups. Often a faculty member will seek a reference directly from a colleague rather than going through formal university channels. Nevertheless, it is still a good idea to channel reference 16 / 596 A.2d 65 (Me. 1991). #17 requests through an administrator who can refer the request to the appropriate individual and at that time remind him or her of the institution's reference policy. 1. performance. Limit references to information necessary to evaluate job 1. opinions. Provide specific examples and illustrations to support 1. for leaving your institution. Do not speculate on an employee's performance or reasons 1. you to provide references. Obtain written consent from departing employees who wish 1. With respect to tenure references, establish a specific procedure for obtaining references and adhere to it. Do not accept references that do not conform to the procedure established for provision of references, as such situations may later be used in litigation as evidence of the reference-provider's improper motives. For example, if your institution has established a cut-off date for comments on tenure candidates, do not accept comments or input received after that date. Similarly, if your school's policy is to only solicit written tenure or employment references, do not take references over the phone. A. Checking Employment References 1. Ask prospective employees to list references and obtain their consent in writing to contact present or former employers. 1. If an applicant will not authorize contact with a former employer, discuss with him/her the reasons for not doing so. 1. performance. Ask applicants to identify any anticipated criticism of work 1. If possible, request references in writing. Note in an appropriate file all attempts to obtain reference information, whether successful or not. Document the answer to the question "Is there anything else I should know about this candidate?"