Politics, Economics, and Society on the Cheren Plains

advertisement

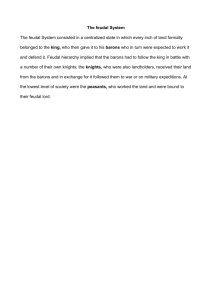

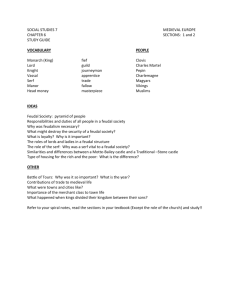

Politics, Economics, and Society in the Cheren Plains (Note: Unlike most of my writings about Thalea, I’m not going to write this from a Thalean point-of-view, but will instead make explicit comparisons with situations on Earth. When discussing complex social systems it’s just a lot easier to be able to refer to examples from real-life history than to try to discuss such things with no context.) Understanding the social systems of the Cheren Plains requires reviewing a bit of Thalean history. The main thing to remember is that, despite (or perhaps because of) the Plains’ rich soil and dense populations, their history is one of almost unremitting warfare. As such, the social and economic system has always been geared toward creating and maintaining military forces. For most of the last two millennia, the social system which filled that duty was the classic feudal system. Kings and other rulers would grant some of their lands to major aristocrats in exchange for military service. This pattern was replicated down the social hierarchy with large landowners subdividing their lands into smaller plots for their own vassals. At the bottom of the hierarchy, this pattern was very similar to the European manorial system – a typical noble would own one or more manors, each with its associated fields, pastures, forests, and water supplies. Some of this land would be worked directly by the lord and his servants, while other parts would be parcelled out to peasant families in return for various obligations, usually some combination of rent (typically paid in kind), agricultural labor (working the lord’s fields during certain times of the year), and military service (either as common foot soldiers or in military support roles such as squires or carters). The lord would use these resources to fulfill his own military obligations, usually specified in terms of a certain number of men, along with all necessary arms, mounts, and provisions, for so many months per year. In addition to their military and economic responsibilities, local lords also typically served in a quasi-governmental role, with power to enforce the king’s laws. It must be emphasized that these relationships were often exceedingly complex. As a result of centuries of inheritances, marriages, and other land transfers, most feudal holdings are non-contiguous, and can be scattered across large areas. An individual farm holding in a manorial village may include a house in the village, a plot of land in the fields, grazing rights in the communal pastures, plus various access and usage rights to harvest fish or timber. At the other end of the spectrum, a major aristocrat may hold hundreds of manors scattered across a large area, and even the individual manors may consist of scattered holdings intertwined with those of other lords. Furthermore, the the relationship between a lords and each of his many vassals, already a multifarious collection of economic, social, military, and civic interactions, varied greatly based on local laws, traditions, individual agreements, and the value of the land involved. One feature of Cheren feudalism that differed greatly from that on Earth was the role of the knight. On Earth the concept of knighthood included most noblemen and was often a generic term for any noble with the proper military training. On Thalea, the concept of knighthood was introduced by the Church of Tedanten during the waning years of the Lemenurian Empire. Knights were religious warriors who renounced family ties and inheritance in order to dedicate their lives to Tedanten as professional soldiers. That model quickly spread to other local religions, who founded their own fighting orders, while some orders were founded without religious affliliations at all, designing knightly codes of a secular, or at least non-denominational, nature. While the early chivalric orders were generally supported by direct gifts from noble patrons (or employers – some orders have always been more mercenary than others), over time many orders were endowed directly with their own feudal holdings to support their members. Typically a noble would grant some portion of his land to a chivalric order dedicated to serving his lord, thus permanently “buying off” his regular military obligations. This practice was often encouraged by kings, who preferred permanent cadres of professional soldiers over the part-time (and often reluctant) feudal levies. In this fashion, many chivalric orders became major landowners in their own right, becoming important and sometimes independent political and economic powers. In this way, endowed chivalric orders bore a close resemblance to the powerful abbeys of medieval Europe, semi-autonomous organizations which sometimes even extended across national borders. But rather than being devoted to religious contemplation they were devoted to military support of a specific sovereign or cause. This would be an appropriate point to comment on the place of religion in the Cheren social system. Cheren priests are paradoxically both more and less influential than their counterparts in medieval Earth. Given their undeniable and often essential miraculous powers, Cheren priests command great respect and are integrated into all aspects of Cheren life. Any king, nobleman, general, or community without the divine support of clerics is doomed to failure, or at least a marginal existence. However, in place of a single church hierarchy with a monopoly on religious power, Cheren culture has more than a dozen allied yet competing ecclesiastical organizations. This drastically weakens their “bargaining power” in social relationships, as any church which demands too much can, at least theoretically, be replaced by the services of a rival church of a more accomodating nature. Furthermore, Cheren religion (with the notable exception of the Church of Fondam) has never gone in much for monasticism, which at its heart is based on the idea of walling clerics off in isolated communities to devote their lives to meditation and prayer. Cheren clerics are in far too much demand for very practical needs, and are usually closely integrated with the general community. Thus, the absence of abbeys. While it’s not uncommon for individual churches to be endowed with lands, much like the chivalric orders (and for much the same reasons, as clerics are a vital part of any military endeavor), they lack the overwhelming economic and social power of the unified medieval Catholic church. So that’s a summary of how Cheren culture was. And this is important because the framework described above still forms the theoretical underpinnings of the modern Cheren social system. Despite centuries of change, the Cheren people still often think of their society and government in feudal terms, even when that model is increasingly anachronistic. The single most pervasive change to Cheren culture is the transition to a cash economy. This has actually been going on for a long time now. A cash economy offers numerous incentives, most importantly that it’s simply far more efficient than the tortuously convoluted details of a typical feudal relationship. The laundry list of rights, duties, and obligations between lord and his vassals/tenants, which are difficult to quantify and often subject to dispute, can be replaced by the simple payment of an annual or monthly rent. The increase in coinage is a boon to trade, making transfers of goods far simpler than the intricacies of a barter system. As more facets of the economy come to be controlled by money, it becomes easier for all parties to quantify value in disparate goods or services and to better manage their resources. Of course the institution most directly served by the easy quantification of obligations is the government. Kings and other sovereigns have often been behind the impetus toward the increased use of money, as it makes almost every aspect of their job easier. It increases the opportunity for direct taxation, eliminating the problems of perishable taxes in kind. It eases the accumulation and transfer of capital for large construction projects like roads, bridges, docks, mines, and fortifications. And most importantly, it’s a godsend for military planning, where the ability to simply pay for soldiers and materiel alleviates the nightmare of military logistics under a feudal economy. Because of these advantages, Cheren culture has been slowly but surely shifting to a cash economy for centuries now, with concomitant evolution in other social institutions. Kings came to rely less on feudal levies and more on a combination of standing armies, mercenaries, and the chivalric orders. The Cheren nobility transformed from a warrior class to a class of wealthy, land-owning aristocrats. The manorial system was fading away, with communal lands being enclosed into independent farmsteads or large-scale plantations and ranches. A small but growing middle class of urban craftsmen and merchants, often explicitly modelling their practices on those of the more mercantile Salman States to the east, was becoming an important part of the economy. Old ties of fealty and patronage were being replaced by new ties of employment, trade, and even incipient nationalism. However, all these changes were slow enough that, with the exception of a few historians, most Cheren people didn’t even realize their society was undergoing a socio-economic revolution. That is, until the foundation of the Empire of Chelenais. When Chelen I conquered the Cheren Plains he found himself in charge of a diverse population, in which each former kingdom, and sometimes even each small region within a larger kingdom, had its own laws, its own feudal traditions, its own coinage, weights and measures, and tax system. Faced with the impossibility of governing such a monstrous hybrid, Chelen set about the task of rationalizing these disparate systems and imposing common rules and standards wherever possible, invariably favoring the “new ways” over the old. Within a matter of decades he made transformed Cheren society in very noticeable ways. Direct taxation replaced feudal obligations wherever possible, while many judicial powers once delegated to local nobles were subsumed back to the emperor. Most of the chilvalric orders not closely associated with powerful churches were “nationalized”, their loyalty re-directed directly to the emperor and their lands administered by imperial appointees. These developments necessitated the creation of nation-wide tax collection and judicial systems, institutions which formed the nucleus of a rudimentary imperial bureaucracy. As might be expected, Chelen encountered resistance to these changes, especially from the aristocrats, who stood to lose the most from his reforms, which bypassed their traditional role in governing the land. From Chelen’s point-of-view, however, this class, which used to be the bulwark of a ruler’s military forces, was little more than a vast collection of legally-privileged parasites who served as the primary impediment to his goal of transforming his empire into a modern state. Unfortunately, they still controlled the vast majority of Chelenais’s land and resources, so he couldn’t move against them directly. Instead he could only chip away at their traditional rights while building up a more loyal government of administrators drawn mostly from the new middle classes. One of Chelen’s most ingenious and successful methods of de-fanging the Cheren aristocracy was the same ploy used by Louis XIV back on Earth – he purposefully encouraged the nobility to complete their long transition from military governors to decadent dilettantes. Just as Louis built Versailles, Chelen constructed the Purple Palace, an extravagant playground in which the nobility was given every opportunity to expend their energy and resources on petty intrigues and useless displays of grandeur. Unlike Louis, Chelen was never able to actually require his nobles to reside in the Purple Palace, but he did his best to encourage them, lavishing favors and praise on those who spent all their time away from their ancestral lands (and thus under his watchful eye) and who bankrupted themselves in order to support a prolifigate lifestyle (thus transferring their wealth into the hands of the middle class craftsmen and merchants who made the clothes and catered the parties). As was mentioned, Chelen never achieved quite the success that Louis did in neutralizing his nobles, but he was well on the way to doing so by the time of his death. Unfortunately, his successors proved less apt at maintaining his policies. Chelen II seemed to understand his father’s dreams, and attempted to continue in his footsteps, but he proved to be at best a mediocre politican. Rather than furthering imperial designs he was forced to spend most of his energy simply preventing the empire from sliding back into its old ways. And almost everyone agrees that Chelen III’s reign has been a disaster. Chelen III grew up in the Purple Palace and ended up being caught in the trap his grandfather had set for others, becoming an ineffective dandy, more interested in the latest fashions and court gossip than in governing his own empire. Which leaves the status of the nobility as a whole in a state of flux. Cheren nobles still enjoy a number of legal rights and privileges not granted to commoners, but few of them mean much without the family connections to back them up. Many nobles have become impoverished, forced to sell of their lands or grant favorable long-term leases to tenants. Some have sold or leased out their land voluntarily, allowing them to invest their wealth into banking or merchant ventures, entering into the new economy with varying degrees of success. Still others have retrenched themselves, buying or forcing out old feudal tenants so that they can hire cheap labor to work their land as vast plantations. The chaos and destruction of the Janus invasion and the succeeding war with Partous has only further aggravated the situation. Large parts of the Plains, especially in the west, have effectively seceded from the Empire. Lip service is still paid to the emperor’s rule, but imperial agents and bureaucrats have been eliminated, ignored, or simply suborned by the locals. In most of these areas the local aristocrats have seized effective control, sometimes with the consent of the urban middle classes, sometimes without. The voice of the rural commoners is invariably ignored, except to be squelched during the increasingly common peasant uprisings. Civil war hasn’t broken out mainly because all parties are war-weary and broke, plus few want to risk “intervention” from the powerful Theocracy of Sonniel to the north or the saber-rattling military governors of Bonne in the west, neighboring powers who would be quick to take advantage of any overt conflict. A few canny observers also worry about the more subtle threat from the Salmano States, whose guildmasters and merchant princes are both the primary buyers of Cheren agricultural exports and the holders of vast amounts of Cheren debt.