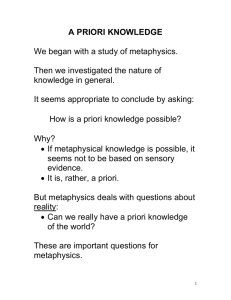

Lecture 8 - A Priori Knowledge

advertisement

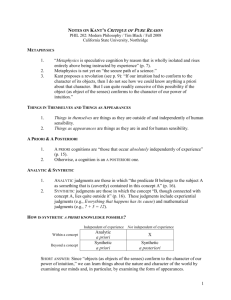

A PRIORI KNOWLEDGE We began with a study of metaphysics. It seems appropriate to conclude by asking: How is a priori knowledge possible? Why? Metaphysical knowledge is not based on empirical evidence. But metaphysics deals with questions about reality. So, the following naturally arises: can we really have non-empirical knowledge of the world? 1 A Kantian distinction Two kinds of judgement: Analytic(al) Predicate already contained in the subject. Synthetic Predicate adds something to the subject. Explains but doesn’t expand a concept. Expands on the subject concept. Based on law of contradiction Requires more than non-contradiction. Examples: Analytic All bachelors are men. All bipeds have two legs. Synthetic The solar system has 9 planets. All dogs are loyal. 2 Kant: all analytic propositions are a priori Kant: all analytic propositions are knowable a priori because they are based only on the law of (non-)contradiction: If X = A & B then: ‘All X are A’ is a priori (true, necessary) ‘Some X is not A’ is a priori (false, nec.) E.g.: bachelor = unmarried & man ‘All bachelors are unmarried’ is a priori (true, necessary) ‘Some bachelors aren’t men’ is a priori (false, necessary) Again: AnalyticA priori 3 What about synthetic propositions? Some are clearly a posteriori; e.g.: propositions about particular empirical matters: ‘The Earth’s surface is 70% water’. The concept ‘Earth’s surface’ doesn’t contain ‘is 70% water’. ‘Women have two X-chromosomes’ The concept ‘woman’ doesn’t contain ‘double X-chromosome’. Such claims are contingent and can only be known on the basis of sensory experience. Call these empirical propositions. All empirical propositions are a posteriori But are all synthetic propositions empirical in this sense? 4 Metaphysical judgments Metaphysical claims are not known or confirmed by experience. E.g.: The future exists o Can’t experience the future. An object that gains a part becomes a new object o Our observations underdetermine this. Other possible worlds exist o They are not connected to our world. All events have causes o Impossible to experience all events. So: Metaphysical judgements are a priori. Key question: Are they analytic or synthetic? 5 The synthetic a priori: the final category Kant: metaphysical judgements are not analytic: The concept ‘future’ doesn’t contain ‘real’. ‘Object’ doesn’t contain ‘mereological constancy’ ‘Possible’ doesn’t contain ‘non-actual concrete world’. ‘Event’ doesn’t contain ‘cause’. We don’t contradict ourselves if we claim the future is unreal, or our world is the only world, etc. So: metaphysical propositions are synthetic. Conclusion: metaphysical propositions are synthetic a priori. 6 How is metaphysics possible? Kant: the central question of philosophy: How is synthetic a priori knowledge possible? The problem: It is easy to see how empirical propositions are known: use your senses. It is easy to see how analytic propositions are known: use the law of (non-) contradiction. But metaphysics requires more than non-contradiction or empirical observation. Either synthetic a priori knowledge is possible, or metaphysics is impossible. 7 How is such knowledge possible? So how could we have knowledge of reality that is based neither on observation nor the law of contradiction? Kant: empiricists and rationalists both assume that knowledge is a matter of the mind reflecting/conforming to reality. But the mind can’t experience enough to have metaphysical knowledge: So, if metaphysical knowledge is possible, then… The world must conform to (reflect) the mind, not the other way around! 8 The ‘Copernican’ turn in philosophy Kant: reality is conditioned by the mind. Time is the form of inner intuition. Space is the form of outer intuition. What does this mean? The world itself is neither temporal nor spatial. The mind has spatiotemporal structure (categories). The empirical world we experience is structured by the mind. In short: the world we experience is spatial and temporal because: 1. Empirical reality is structured by our minds. 2. Our minds have space and time ‘built into’ them (as ‘forms’ of experience or, as Kant calls it, ‘intuition’). 9 More categories Similarly, the mind is structured by other categories that form the empirical world: Universal causality, moral law, etc. Does this mean that we each live in our own worlds? After all, what if my mind is structured differently from your mind? If Kant is right, then we live in different empirical realities. Kant: the structuring categories are universal and necessitating. That is: They are part of every mind. They require that all of empirical reality conform to them (not just the part you experience). 10 Synthetic a priori knowledge So, synthetic a priori knowledge is possible because: 1. Empirical reality is conditioned by the mind’s universal, necessary categories. 2. We have direct access to our minds, so we can use pure reason, not the senses, to uncover the structure of reality. 11 General and particular Note that the mental categories determine a general structure of reality, such as: All objects are spatially related to each other. All events are temporal related to each other. All events have a cause. The categories do not determine particular matters of fact, such as: John is to the left of Sally right now. WW II ended in 1945. John’s cat has yellow fur. The former can be learned by pure reason; that latter require empirical investigation. Put another way: metaphysical propositions are not empirical propositions (even though both are synthetic). 12 Objection This is implausible; why not just reject synthetic a priori knowledge? Kant: Claims of math, geometry and pure (mathematical) science are synthetic a priori. Can’t reject these! Example: 7 + 5 = 12. Kant: the concept ‘add 5 to 7’ does not contain the concept ‘12’ You can think of the first without the second. Therefore, math is synthetic a priori. Similarly: Interior angles of all triangles add to 180o. Distinct parallel lines never meet. Law of conservation of mass. 13 In sum 1. Synthetic a priori knowledge is possible only if the mind conditions reality. 2. Math, geometry and theoretical science provide certain knowledge. 3. They are all synthetic a priori. Therefore: 4. The mind conditions reality. 5. We can know non-analytic, necessary truths by analyzing the structure of human thought (pure reason). 6. Metaphysics is possible. 14 Empiricist critique of a priori knowledge How can the empiricist account for our knowledge of necessary truths? E.g. math and logic. These can’t be verified empirically. No finite number of observations can render a universal claim certain. E.g. problem of induction. 15 Mill’s empiricism Mill: logical/mathematical claims are inductions based on many, many observations. So much evidence in their favour that they seem necessary, but they are not. Ayer: this is not plausible. Of course we learn logic and math empirically, by being taught. But once we understand them, we see that they are not verified the same way as empirical claims. Any cases that might seem to refute such claims are better explained as cases of error. Examples Not, 2 + 2 = 5; rather, I miscounted. Not really a Euclidean triangle. 16 Analytic/synthetic Empiricist account of the distinction: Analytic claim True in virtue of the meanings of the words involved. Synthetic claim True in virtue of the facts of experience (and meanings). Ayer: there are no synthetic a priori claims. All truths of math and logic are in fact tautologies, true in virtue of the meanings of their words. E.g.: Or = one or the other is true. Not = p and not-p have opposite truthvalues. If you know these meanings, you know that ‘p or not-p’ must follow—it is simply what the meanings add up to. 17 Tautologies Ayer: analytic propositions are rules or stipulations for how to use our language. They tell us how our words relate to each other; how our language hangs together. E.g.: ‘If p implies q, and p is true, then q is true’. This is a rule that guides how to use your words. Math and logic are rules we agree upon in using our language. 18 Analyticity and necessity Analytic truths can be known a priori: They make no claims about the world. They are only conventions that we adopt to guide our language. As soon as you learn your language, you know them. So, there is no possibility of confirming or denying them in experience. They are necessary because they guide your language. To violate them is to be guided by them and also to break them. That is a simple contradiction. Hence, they are necessary. 19 Another example Stipulation: ‘shmat’ = ‘anything with four legs’. As soon as you know this, you know a priori that there are no five legged shmats—tautology. But you need to use your senses to determine whether there are in fact any shmats. 20 Empiricism and metaphysics Ayer: a priori knowledge of the world is impossible. Necessary, universal claims are all analytic. These only depend on the meanings of words and are devoid of factual content. Therefore, metaphysical knowledge is impossible—at best it is linguistic analysis. E.g.: ‘all events have a cause’. Can’t be verified empirically. Not true in virtue of meanings of words (+ logic/math). Therefore, it is nonsense. 21 The point of a priori knowledge Ensure empirical claims are consistent. Determine the implications of factual claims. Determine the implications of claims that are too complex for us to see directly. E.g. complex mathematical claims are verified by smaller, a priori steps. 22 Math and analyticity What about Kant’s claim? Isn’t 7 + 5 = 12 synthetic? Ayer: Kant gives two definitions of analytic: 1. Law of contradiction 2. Can’t think of subject without also thinking of predicate. It is true that 7 + 5 = 12 isn’t analytic by #2. But that is just a psychological principle, so it’s irrelevant. 7 + 5 = 12 is analytic by #1: Once you know the meanings of ‘7’, ‘5’, ‘12’ and ‘+’, you see that ‘7 + 5’ is synonymous with ‘12’. So, the claim can’t be denied without violating your definitions. Same applies to geometry: everything follows by definition. 23 Convention Ayer: because analytic propositions are independent of the facts, we could have chosen different conventions. However, whichever conventions we were to choose, they would form tautologies and would therefore be necessary. In other words, necessity (analyticity) is relative to a set of linguistic rules. Do you agree: is it plausible to suppose we might not have settled on: P v ~P? 2 + 2 = 4? etc.? 24 Two more objections First: Isn’t ‘there are no synthetic, a priori truths’ itself a synthetic a priori claim? Second: Some logical laws are not based on the meanings of words. E.g.: Bivalence: every proposition is either true or false. This doesn’t follow from the meaning of ‘true’ or ‘false’. It is a logical principle, not a semantic one. How can the empiricist account for this? 25 Important categories to keep distinct Epistemological A priori proposition A posteriori prop. Known independently Known on the basis of sensory evidence of sensory evidence Semantic Analytic prop. Predicate contained in subject Synthetic prop. Predicate adds to subject Metaphysical Necessary truth Couldn’t be false Contingent truth Might have been otherwise 26 Summary of positions Kant All a priori knowledge is of necessary truths Some necessary truths are synthetic So, we can have synthetic a priori knowledge Metaphysics is possible Ayer All a priori knowledge is of necessary truths All necessary truths are analytic There is no synthetic a priori knowledge Metaphysics is impossible. 27