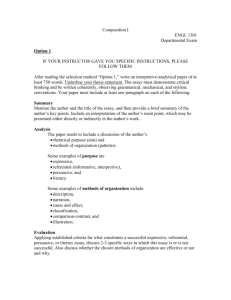

THE PERSONAL / LITERARY ESSAY

advertisement

THE PERSONAL / LITERARY ESSAY When essayists sit down to write for a living, they usually compose what we call a “personal” or “literary” essay. We use both terms, not exactly interchangeably, because we need both of them to capture what happens in a good essay of this sort. We call them personal essays because the reader expects that the voice they hear in the essay is the author’s autobiographical voice. The reader hears the writer talking to them as him- or herself. Almost always, this kind of essay is expected to be written in the first person; that is, using “I” constructions. (We should note, however, that although first person is acceptable / expected, we still must live by the same rules we live by in everyday life: people who can only talk about themselves tend to get boring after a while, or, even worse, we mistrust them because they seem not to talk about the world but only about their [fragile] psyches). The point is this: the reader invites the writer to be personal, but any autobiographical references, experiences, etc. must somehow lead the reader beyond the merely personal into the realm of the human. Another way to put this is: in a good essay of this type, the individual, personal, or idiosyncratic must be used to bring about an insight not just into the writer’s condition—but into the human condition. The personal must bring about the universal. A good example of this is E. B. White’s essay, “The Ring of Time,” in which he talks about a visit to a circus rehearsal in Sarasota, Florida. He and some other observers watch a young girl practice her horseback acrobatics… But the essay is not about acrobatics; from the title you can tell it’s about “time.” Not everyone has the personal experience of the circus, but everyone has to cope with the experience of time. Get it? We call them literary essays because we expect the writer to use artful devices of language to build their essays. We would not expect the literary device of rhyme, for example, which finds its better home in poetry, but we would see an essayist toying with the structures and rhythms of sentences, the presence of metaphor and symbol, as well as bigger structural devices like foreshadowing, contrast, irony, and the like. So, with this in mind, I do not care what the specific topic is of your Essay 4 so long as it is personal and literary—artfully constructed to present autobiographical experience in such a way that it sheds light not just on you but on the human condition (don’t write the essay that talks about how you felt when your first pet died unless that event can move beyond your own personal feelings and into the realm of pets, death, petdeath, and some interesting insight or observations about any or all of them). I am reminded of an opening line from the essayist Annie Dillard (the title of the essay I cannot remember): “Children have no sense of wonder.” This is a provocative claim because it goes against what we’ve all been taught culturally to believe (that’s the “human condition payoff”), and the way that Dillard uses her personal experience and literary technique to “prove” the claim really changes who you are after you’ve read the essay. That what a good essay does: it changes the reader.