THE MIGRATION OF FINANCIAL REPORTING PRACTICES FROM

6

7

8

9

10

4

5

2

3

THE MIGRATION OF FINANCIAL REPORTING PRACTICES FROM POSITIVISM

TO RELATIVISM: CAUSES AND POSSIBLE REMEDIES

Prof Christo Cronje

Department of Financial Accounting

27 November 2012

CONTENT PAGE NUMBER

1 INTRODUCTION, PROBLEM STATEMENT AND PLAN OF ACTION 2

POPPER: COMMUNICATION MUST BE POSSIBLE

DIFFICULTIES OF COMMUNICATION: MICHAEL POLAMYI

KUHN AND INCOMMENSURABILITY

FEYERABEND AND BEYOND

DOOYEWEERD

APPLICATION OF MODAL ASPECTS

TOWARDS DOOYEWEERDIAN FINANCIAL REPORTING PRACTICES

INTERCONNECTEDNESS OF THE ASPECTS

CONCLUSIVE REMARKS

BIBLIOGRAPHY

7

8

8

14

3

5

2

3

14

16

THE MIGRATION OF FINANCIAL REPORTING PRACTICES FROM POSITIVISM

TO RELATIVISM: CAUSES AND POSSIBLE REMEDIES

1 Introduction, problem statement and plan of action

Communication in science, including the accounting sciences is one of the most precious valuables to create meaning and progress, often taken for granted. Communication is one of the elements that grants credibility and legitimacy to science (Colletto, 2008:446). How did it then happen that even the possibility of scientific dialogue is questioned in the most recent philosophies of science? This will be the first question of this lecture. The second question is: What remedies could be offered, from a

Dooyeweerdian point of view? The third question is: Is there room to increase the commonality between the preparer and the user as a prerequisite for conveying meaning in corporate annual reports of companies?

The first part of this lecture deals with how contemporary humanist philosophy of science got caught up in a gradual loss of confidence concerning the possibility of sound scientific communication among scholars holding on to different paradigms or presuppositions. The second part covers some responses provided by Dooyeweerd to the bleak possibility of a communication crisis. The resources deployed by

Dooyeweerd’s philosophy are argued to constitute valuable tools to create a more hopeful attitude towards scientific dialogue. Finally a discussion is added regarding the improvement of accounting information disclosures.

2

The historical survey will start from Karl Popper, a philosopher who was still quite optimistic about the possibility of communication. This will provide a frame of reference against which the subsequent loss of confidence and the adoption of more pessimist and relativist views will become more apparent.

2 Popper: communication must be possible

Popper took the possibility of communication for granted. However, he did not simply take a positivist approach, which looks for a kind of neutral language, capable of eliminating the problems implicit in ordinary language that harbours nonscientific and “metaphysical” notions. The positivists tended to identify verifiability with meaningfulness: linguistic statements that are non-verifiable do not have meaning. For Popper

(1963:38-39), statements and theories can be non-scientific without necessarily being “meaningless, or nonsensical”.

With the appearance of Kuhn’s works the issue of incommensurability receives the attention of Popper, with a certain amount of irritation. He realises that the “myth of the framework” is at stake: the conviction that ideas can be debated only if certain basic assumptions are shared. For

Popper such an approach is wrong, as it is a form of relativism, actually the central bulwark of relativism (Popper, 1970:56). Popper is of the view that the gap between old and new theories is always relative. They are both footsteps in the way towards the approximation of truth.

Communication must therefore be possible.

3 Difficulties of communication: Michael Polanyi

Polanyi at first followed a “conservative line” (Coletto 2007:74, footnote

53) recognising the existence of several types of pre-scientific presuppositions and frameworks and emphasises the fact that all

3

scientists share those ideals and “premises”; therefore the scientific communities show a high degree of consensus, and communication is never doubted.

Subsequently a “late modern” line of thought makes its appearance

(Coletto, 2007:74, footnote 54), from which one learns from Polanyi that the frameworks behind science can indeed be very different from each other, creating controversies. Now scientific thinking seems to be “locked up” within a certain framework. Scientific dialogue can therefore not be taken for granted any more. Furthermore, formal operations relying on one framework of interpretation cannot demonstrate a proposition to a person who relies on another framework. Supporters of a certain framework may not be understood by supporters of a different one, because “they must first teach them a new language” (Polanyi,

1958:151). “They think differently, speak a different language, live in a diff erent world” (Polanyi, 1958:151-2).

Polanyi provides a system which is more open than Popper’s to the recognition of the difficulties of communication in science. The philosophers dealt with in the next sections welcomed specifically the

“late modern” line of Polanyi’s philosophy in their own systems of thought.

4 Kuhn and incommensurability

For Kuhn the possibility of communication is more problematic when compared to Polanyi. Scientists who accept the same paradigm can still communicate, while it is almost impossible to communicate with scientists who do not accept the same paradigm. According to Kuhn, only one paradigm can dominate a certain field of study in a certain period, which preserves a considerable degree of communication. However in times of crisis and transitional periods, the problem of communication comes to

4

the fore, when revolutions divide the scientific community between an old and a new generation. “During revolutions” says Kuhn (1970a:111),

“scientists see new and different things...we may want to say that after a revolution scientists are responding to a different world...what were ducks in the scientist’s world before a revolution are rabbits afterwards”. Not only the perspective, but also the phenomenal world change. A different world appears, with difficulties in communication, as the conversion or transition between competing paradigms cannot be made a step at a time.

There are evidence in The structure (cf. Kuhn, 1970a:129, 130, 150) especially in its Postscript that Kuhn changed his radical views on communication. Scientists are now able to listen to each other.

The stimuli that impinge upon them are the same and their general neural apparatus is the same. They share a history and in addition both their everyday experience and most of their scientific world and language are shared (Kuhn, 1970a:201).

Kuhn started to limit and narrow the concept of incommensurability.

During the 1960’s the incommensurability of two theories touched three aspects:

differences in the phenomenal world;

differences in the selection of problems and standards for their solution; and

differences of meaning.

Towards the late 1960’s and early 1970’s the first two aspects were abandoned and incommensurability focussed only on change of meaning

(Kuhn, 1970b, 267-268). Two theories were now called incommensurable when there is “no language into which at least the empirical

5

consequences of both can be translated without loss or change” (Kuhn,

1970b:266). A neutral observation language could be used, but there is no such language.

At the beginning of the 1980’s the argument concerning a neutral observation language disappears and untranslatability is involved in explaining incommensurability.

”If two theories are incommensurable they must be stated in mutually untranslatable languages ” (Kuhn, 2000:34).

Kuhn (2000:35-

37) declared that “the claim that two theories are incommensurable is more modest than many of its critics have supposed”

(Kuhn, 2000:36). A “taming” of incommensurability therefore took place.

The adoption of two important ideas played a role in the ‘taming” of incommensurability. The first one entails that incommensurability does not imply incomparability (Kuhn, 1979:416) and secondly that there remains a continuity between different traditions of normal science.

Therefore the empirical potential of incommensurable theories can indeed be compared, as they have interconnections. A certain type of continuity remains even between incommensurable theories (Kuhn, 2000:36).

Kuhn therefore gradually reduces and limits some of his radical claims, but shows that the gradual move towards relativism of contemporary philosophy of science is not simply a linear process, but a process that shows pauses and contradictions. Incommensurability becomes an established concept, which holds a potential threat to communication and to the credibility of science. Kuhn hesitated to move completely towards relativism, but these hesitations were completely abandoned by

Feyerabend, who accepted the challenge of relativism and pluralism.

\

6

5 Feyerabend and beyond

The theme of incommensurability is introduced, in Against method, as something that anticipates the future radical character of philosophy of science. His anarchistic approach “...is liable to paralyse the brains of almost every one” (Feyerabend, 1975:214). According to Feyerabend, rival schools and paradigms have been proliferating and co-existing in all disciplines. He states that a discovery, or a statement, or an attitude is incommensurable with a theory or framework if it suspends some of their universal principles (Feyerabend, 1975:269). Feyerabend switches the focus from linguistics and translation to the worldviews, principles, beliefs and ontological convictions supported by these theories. He is convinced that statements and theories are dependent on some fundamental framework and when the basic assumptions of such a framework are denied by another framework or by statements or by new theory, the two competing systems become incommensurable. To show that incommensurability exists, he refers to different styles in painting

(Feyerabend, 1975:230 ff.) where it can be said that the cosmology implied in these paintings is incompatible with our modern conception of the world and of man (Feyerabend, 1975:230). He comes to the conclusion that it is an illusion even to suppose that incommensurable theories deal “with the same subject matter”. Incommensurable theories therefore deal with totally different facts.

Communication between scientists in such cases becomes simply impossible, but according to Feyerabend it is still possible, for example, to refute incommensurable theories. They can be refuted by comparing their internal contradictions. Feyerabend admits that in the absence of

7

commensurable alternatives “these confutations are quite weak, however”

(Feyerabend, 1975:284), and “greatly reduced in strength” (Feyerabend,

1975:285). Although one can still criticise incommensurable theories, with

Feyerabend the point is reached of a loss of communication. Feyerabend wanted to use the arguments of rationality in order to undermine rationality itself (Feyerabend, 1975:33). The impression is that he uses communication to prepare for a breakdown of (scientific) communication

(Coletto, 2008:455).

Now the possibility of incommunicability becomes a real challenge, which is accepted in postmodern times, with an attitude which is a mixture of celebration and anxiety. Baudrillard becomes concerned and in his view science and technology have caused the implosion of communication in general, exactly by exploiting its possibilities. Baudrillard (1984:129) asserts that in our epoch we have entered the “third order of simulacra”, which is an order of simulation a nd is “controlled by the Code”.

Communication becomes mis-information and invades both public and private space. Communication was supposed to constitute the real, but exactly through its reproductions it has created the hyper-real, which is just a simulation without origin or relation to any reality. Science has not only experienced the “internal” difficulties of communication, but has also prevented the possibility of true communication in contemporary society.

Lyotard is less pessimistic and invites one to stop longing for a science in which consensus is one of the most important values. He advocates that postmodern science should not seek to create consensus, but rather dissensus. He criticises the philosophy of Habermas who seeks for consensus through dialogue and which is based on the meta-narrative of emancipation (Lyotard, 1984:60). Lyotard believes in the necessity of

8

emancipation, but hopes to achieve it via the power of dissensus, as consensus can be the end of freedom and debate, For Lyotard, it is dissensus that allows the experience of liberation.

According to Lyotard, postmodern science can open up new and exciting perspectives by resisting consensus. Dialogue and communication do have a legitimate place, but it does not matter whether they are effective.

It is actually better if such dialogue does not reach any result, if consensus is avoided it will keep the game going.

For Dooyeweerd, communication and cooperation between scientists of different persuasions is indeed possible. His philosophy is not bound to an oppositional attitude.

The second part of this lecture considers an application of Herman

Dooyeweerd’s aspects of temporal reality to financial reporting practices in order to enhance their diversity and coherence of meaning, thereby improving the possibility of communication.

6 Dooyeweerd

Dooyeweerd held that the modal aspects cannot be separated in reality

(Basden, 2011:1), so the coherence of the aspects is also discussed. The following example is used by Basden (2011:1) to illustrate the aspects of temporal reality:

Suppose you are writing a letter: Many different kinds of question may be asked about what you are doing, such as: How many words, paragraphs, sections are written? How large a sheet of paper is being written on? Is the writing fast or slow? Might the writing (ink) fade over time? Do I write badly when ill? How do I feel while writing? Is the light too dim to see what I am writing? Is it clear what I want to write about? Do I have a plan and structure? How can I best

9

express what I want to say? What phrasing suits the intended readers? What connotations will the word carry? Do I have to keep to a word limit? Is my writing interesting or boring? Does what I say all hang together? Am I doing justice to the topic? To the readers?

Do I write with goodwill and generosity? Do I believe in what I am writing? Is it important?

According to Basden (2011:1) each question indicates an aspect of the writing activity. An aspect is a way of looking at something, a way in which things can be meaningful. Only in relation to each other can the modal aspects be properly understood, and be employed as tools to bring forth multiple and meaningful financial reporting practices.

Aspects are closely tied to the very structure of temporal reality, as spheres of meaning, which makes being possible, and spheres of law, which makes both functioning and normativity possible (Basden, 2011:3).

Aspects are spheres of meaning, providing different ways in which things in all temporal reality can be meaningful. This is often referred to as aspectual meaning . Aspects are spheres of law, which is the foundation for functioning, repercussions and normativity of and in all temporal reality

(Basden, 2011:3). This is often referred to as aspectual law.

It is important to note that no aspect can be reduced to others in terms of its meaning and law, nor can any be satisfactorily explained in terms of others. Dooyeweerd conceptually separated the aspects in order to discuss them, but he also stressed the importance of non separation in temporal reality, because all aspects work together (Basden, 2011:3).

Each as pect contains ’echoes’ of all the others, and each is involved in a mutual inter-dependency with others (Basden & Burke, 2004:357). In

10

other words the different aspects are interconnected and weaved together.

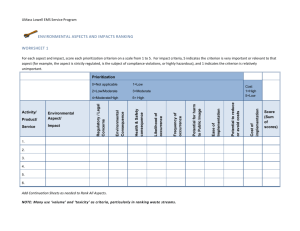

Figure 1: Inter-aspect relationships

Source: Basden (2011:4)

Type

Order

Description

The aspects form a sequence, not from lower to higher, because Dooyeweerd held that all aspects are equally important, but from earlier to later. In this sequence, aspects both retrocipate earlier (foundational) aspects, and anticipate later aspects.

Dependency Here aspects ‘need’ each other, differently in the anticipatory and foundational directions. In the foundational direction the functioning in an aspect depends on good functioning in earlier ones; for example social functioning depends on good lingual functioning. In the anticipatory direction an aspect’s meaning is not fully realised without reference to meaning from later aspects; for example the lingual aspect is rather, though not entirely, sterile if not used to enable social functioning.

Analogy Here the meaning of each aspect is echoed in the others.

For example, we say an economy ‘grows’ (biotic analogy in the economic aspect).

Reaching out

Functioning in an aspect always involves another as target or object; for example we can have a feeling of space.

11

7 APPLICATION OF MODAL ASPECTS

According to Basden (2011: 5) fifteen aspects of temporal reality can be applied and may be read in any order.

The first three – quantitative, spatial and kinematic – are what

Dooyeweerd called mathematical aspects because they are prephysical. The next three

– physical, biotic and psychic/sensitive – are pre-human aspects, in that they govern material, plants and animals, though they also apply to humans. The next three

– analytical, formative and lingual - govern individual human cognition.

The next three – social, economic and aesthetic – are aspects of our living together. The final three aspects

– legal, ethical and pistic/faith

– are especially important in the health of society.

8 TOWARDS DOOYEWEERDIAN FINANCIAL REPORTING

PRACTICES

As far as the accounting sciences are concerned, accounting is generally regarded as the language of business. Preparers of financial reporting practices encode their message in an accounting language that needs to be decoded by users to enable them to understand and use the information properly. In order to convey meaning successfully, the sender and the receiver of a message need to use the same method to encode and decode the message, that is, there needs to be some commonality of language between the two parties (Gouws & Cronjé, 2011:43). The accounting sciences use two types of financial reporting practices namely statutory financial reporting practices as well as contextual reporting practices. The statutory financial reporting practices still have a strong emphasis on positivism and frameworks. Where accounting phenomena

12

is difficult to measure and control (for example intellectual capital), accounting practices and disclosures migrate towards relativism, taking the form of contextual disclosures, which could result in challenges such as incomparability and loss of meaning. Applying the modal aspects of

Dooyeweerd will definitely make room to increase the commonality between the preparer and the user as a prerequisite for conveying meaning in corporate annual reports of companies (Cronjé, 2012:16).

As far as accounting and accounting disclosures are concerned, concrete reality can be observed through fifteen aspects (Dooyeweerd, 1984, 2:1-

318). They are modes of reality and modes of our experience at the same time. The economic aspect would entail the qualifying aspect for accounting disclosures, but the other aspects would also be sources of important considerations when deciding on how the information is to be reported and disclosed.

8.1 QUANTITATIVE MODAL ASPECT

Basden (2011:5) asserts that we experience the quantitative aspect (as a sphere of meaning) most intuitively and directly as one, several and many , and comparisons of less and more , and the quantitative aspect introduces a fundamental ‘good’ that enables temporal reality to exist

(and mathematics to be foundational): reliable amount and order .

Users need to understand the disclosures being depicted in corporate annual reports. For this purpose use needs to be made of numbers, but numbers need to be complemented with descriptions and explanations

( dependency in the anticipatory direction ). Statutory disclosures could benefit if more use is made of descriptions and explanations in order to

13

faithfully represent financial phenomena, which is one of the qualitative characteristics of financial reporting.

8.2 SPATIAL MODAL ASPECT

According to Basden (2011:6) we experience the spatial aspect directly and intuitively as here, there, between, around, inside and outside.

Spatial properties include shape, position, size, angle, orientation, proximity, surrounding, overlap, and so on. Things that gain their meaning from the spatial aspect include particular shapes (circle, triangle, line, spiral, etc), angles, distances, holes, space, area, dimension and so on.

Simultaneity and continuity are two things that are introduced into temporal reality by the spatial modal aspect.

The use of graphs, pie charts, illustrations, visual representations, colour

(an anticipation of the aesthetic aspect) and photos and so on will enhance the meaning of financial reporting practices.

8,3 KINEMATIC MODAL ASPECT

The kinematic aspect is described by Basden (2011:7) as an intuitive experience of going and continuous flowing. Going and flowing imply backward and forward, which were meaningless in the spatial aspect.

According to Basden (2011:8), expanding, morphing, rotation, route, path and speed and properties like fast, slow, dynamic are some other kinematic concepts. Change and dynamic variability are introduced by the kinematic aspect into temporal reality.

Financial reporting practices need therefore to undergo dynamic variation and change in order to stand the test of time. Dynamic variation and change are necessary to introduce new ideas and to discard old practices

14

no longer relevant. A variety of virtual technologies can be used to make financial reporting practices more meaningful to users.

8.4 PHYSICAL MODAL ASPECT

Basden (2011:8) discusses the physical modal aspect as an intuitive and most direct experience of forces, energy and matter. With the physical aspect temporal reality is transformed continuously from one state into the next in a way that persists and cannot (usually) be undone or reversed. The physical aspect thus introduces to temporal reality features such as irreversibility, persistence and causality.

Documents as we encounter them in everyday life are complex and diverse things (Basden & Burke, 2004:352), whether on paper, computer disk or on the World Wide Web. This is also true for corporate annual reports. The different media on/through which to convey the financial disclosures in the best meaningful way need to be considered. Will paper, sound or the electronic media be used and how can they be preserved and not harmed? Will the materials of which they are made interact with the air or light and change chemical composition so that they decay or fade (Basden & Burke, 2004:358)?

8.5 ORGANIC MODAL ASPECT

We experience the organic aspect intuitively as living as organisms in an environment. (Basden, 2011:10). The organic aspect introduces to temporal reality the possibility of distinct entities that can sustain themselves within their environment, dependent on it but not wholly controlled by it, and reproduce after their own kind (Basden, 2011:10).

Many organic concepts find analogy in aspects where distinct entities are

15

important. Concepts such as birth, growth, maturity and environment have a clear analogical meaning for economic entities (Basden, 2011:10).

Financial reporting practices need to be in transition all the time, and need to be expanded until a maturity stage is reached. Redundant ones need to be discarded to make place for better ones. This is therefore an ongoing process and the ultimate aim should be to enhance the meaning of financial reporting practices.

8.6 SENSITIVE MODAL ASPECT

In this case we experience the sensitive/psychic aspect intuitively as feeling, sensing and responding (Basden, 2011:10), which include sentience and the senses (eyes, sight and seeing, ears, sound and hearing, nose, aroma and smelling as well as emotion, mental activity

(memory, perception, pattern recognition) and instinct. This aspect introduces to temporal reality interactive engagement with the world (the world as it can be sensed) (Basden, 2011:11).

Financial reporting therefore needs to be done in such a way as to ensure an interactive engagement with stakeholders, taking into account their special needs for meaningful information through proper feedback systems. Entities must know who their user groups are and this can be established through interactive engagement with all the various role players. Integrated reporting could play a major role in achieving an interactive engagement with stakeholders.

8.7 ANALYTIC MODAL ASPECT

Basden (2011:11) suggests that we experience the analytical aspect intuitively as conceptualising (of something meaningful to us), clarifying

16

(separating ‘this’ from ‘that’), categorising (differentiating ways of being meaningful), and cogitating (thinking that involves these). Dooyeweerd

(1984, 2:39) explains that analytic thought entails the setting apart what is given together. Basden (2011:11) states that one possibility this introduces to temporal reality is the ability to think independently of the world as given and to undertake theoretical thinking.

Financial reporting practices do make extensive use of the analytical modal aspect to conceptualise and produce distinctly meaningful and relevant information with predictive and confirmatory value, consisting of categorisations, for example the categories of the statement of financial position and notes, that also enhance comparability. However, it is important that financial reporting practices not be reduced to only the analytical aspect, but also to operate by reference to all the other spheres of meaning (aspects). This will ensure that disclosures will be made following a balanced approach.

8.8 FORMATIVE MODAL ASPECT

Basden (2011:12) contends that we experience the formative aspect as deliberate creative shaping of things, usually with some end in mind and include the shape of concepts into concept structures, words into sentences, as well as activities such as forming, designing, processing and innovation. A possibility that the formative aspect introduces to temporal reality is achievement and innovation (Basden, 2011:12). This aspect makes changes and achieves things in the world.

Deliberate creative shaping of financial reporting practices to enhance decision usefulness, is an ongoing process. Much progress has been

17

made with the growth of contextual information in corporate annual reports, for example, the section on management commentary, forwardlooking information and so on. The introduction of integrated reporting is another achievement for making information available to heterogeneous users. Much of the financial reporting practices that are formed by the accounting profession have symbolic value, but this cannot be understood from the formative aspect. It anticipates the lingual aspect

(Basden, 2011:13).

8.9 LINGUAL MODAL ASPECT

Here, we experience the lingual aspect intuitively in expressing, recording and interpreting Basden, 2011:13). A possibility that the lingual aspect introduces into temporal reality is externalisation of our intended meaning (Basden, 2011:13). Words that express something meaningful from the perspective of the lingual aspect include (Basden,

2011:13) : ‘write’, ‘read’, ‘gesture’, signal’, ‘record’, ‘quote’,

‘understandable’, ‘expressive’, ‘sign’, ‘symbol’, ‘phoneme’, ‘word’,

‘sentence’, ‘paragraph’, ‘vocabulary’, ‘language’, ‘noun’, ‘verb’, ‘adjective’,

‘text’, ‘diagram’, ‘media’, ‘data’, ‘information’, ‘meaning’ and so on.

Financial reporting practices could therefore make use of, for example, narrative disclosures in order to enhance understandability. Disclosures should be such that stakeholders can make meaningful decisions with ease. According to Basden (2011:14), negative in the lingual aspect is anything that prevents adequate expression and understanding of what was meant, which includes unintentional problems like the inability to express oneself and lying, obfuscation and equivocation.

18

8.10 SOCIAL MODAL ASPECT

We experience the social aspect intuitively as we, us and them: associating, agreeing and appointing (Basden, 2011:15). A possibility that the social aspect introduces into temporal reality is company, which is togetherness, respect and courtesy (Basden, 2011:15). The social functioning of business is ‘lead’ by the economic aspect. Economic entities have a social contract with different user groups.

Financial reporting practices need to be developed to ensure that disclosures of relevant information are done to heterogeneous users, for example disclosure of environmental aspects, which embrace the effects that an entity’s products and/or services may have on the environment, may be important to environmental pressure groups. Good and bad news about environmental aspects of entities are normally addressed in the contextual disclosures section of corporate annual reports. The social aspects encompass values and ethics, and reciprocal relationships with stakeholders other than just the shareholders.

8.11 ECONOMIC MODAL ASPECT

We experience the economic aspect intuitively as managing limited resources frugally and a possibility the economic aspect introduces to temporal reality is sustainable viability/prosperity ( Basden, 2011:11).

The economic aspect includes the familiar financial aspects as well as the nonfinancial ones and sustainability relevant to the business of an entity.

Timeliness and the cost of providing are also aspects to consider. The nonfinancial aspects will generally be disclosed in the contextual disclosure section of corporate annual reports.

19

8.12 AESTHETIC MODAL ASPECT

According to Basden (2011:17), primarily in harmonising, enjoying, playing and beautifying, do we experience life in its aesthetic aspect.

In order to make the financial reporting interesting, use can be made of graphic designers. The art of graphic design is to provide the best possible of any subject matter

– whether it is an annual report, a brochure or a brand concept (Cronjé, 2008:249). Use can be made of colour, photos, graphics and graphs in order to portray various aspects of the company’s business such as industrial plants or products. In this way information can be provided succinctly, interestingly and meaningfully to ensure that all information hangs together.

8.13 LEGAL MODAL ASPECT

For Basden (2011:18), we experience the legal aspect as appropriateness and due. The legal functioning depends on the earlier aspects, for example the aesthetic aspect insofar as there must be a

“well-balanced harmony of a multiplicity of interests” (Dooyeweerd, 1984,

2:135). Legal functioning is responsibility (Basden, 2011:18). A possibility introduced by the legal aspect is due for all (Basden,

2011:18).

Stakeholders have legal right to relevant information, faithfully represented that would be reported on time, taking into account factors such as materiality and the cost of providing such information.

20

8.14 ETHICAL MODAL ASPECT

The ethical aspect is experienced intuitively as attitude (Basden,

2011:18) and here we go beyond what is due, giving more than necessary. Two good possibilities seem to be introduced to temporal reality by the ethical/attitudinal aspect: to permeate reality with extra goodness, beyond the imperative of due, and to permeate society with a generous attitude (Basden, 2011:19).

Preparers of corporate annual reports need an ethical state of mind in order to faithfully represent credible information through the use of financial reporting practices for the benefit of users.

8.15 PISTEC MODAL ASPECT

We experience the faith or pistic aspect intuitively in vision, commitment, certainty and belief (Basden, 2011:20), where vision is a deeply-assumed view of what is ultimately meaningful. Vision motivates commitment. Pistic is that immediate certainty which manifests itself in practical life, by which we live moment by moment (Basden, 2011:20).

Good possibilities for temporal reality include, courage, loyalty, hope and meaningfulness (Basden, 2011:20).

The vision and mission statement are normally covered in the Chairman’s statement. Other disclosures that could be made would include aspects such as strategy, forward looking information and the assurance relating to the future going concern of the entity.

21

9 INTERCONNECTEDNESS OF THE ASPECTS

The aspects can actually not be separated, but are interwoven as a result of their multi-aspectual functioning and interaction. They are of equal importance. In this lecture aspectual functioning means different ways of looking at financial reporting practices. According to Basden (2011:24), absolutisation (undue elevation) of any aspect brings harm because it breaks inter-aspect coherence and leads to other aspects being either ignored (example: positivism) or explained away in terms of the favoured one (example: subjectivism). Further research and discussions of

Dooyeweerd’s aspects are necessary to also benefit the transition and formation of financial reporting practices.

10 Conclusive remarks

The development of the discussion (in contemporary philosophy of science) concerning the increasing pessimism about the possibility of sound scientific communication among scholars holding to different

“paradigms” culminating in the theme of incommensurability has been explored. The possibilities to compare certain standpoints or to entertain a dialogue between academic schools holding to different presuppositions have also been explored. In the second part of this lecture a

Dooyeweerdian response has been suggested in order to provide an alternative to the dilemmas encountered within recent humanist philosophy of science, including the accounting sciences.

The nature-pole, inspiring positivism and leading to the idea of “neutral” facts, encompasses the dialectical rival of the freedom-pole (Dooyeweerd,

1984, 1:190-495). The ideal of the free creativity of the knowing subject

(which gradually gained the primacy during the twentieth century) entails

22

the “freedom pole” of the humanist ground motive. The freedom-pole encompasses the existence of totally different frameworks of thought, languages, and finally totally different worlds. The common playing field of a creational order is then rejected in favour of a plurality of language games, frameworks and premises.

In this perspective, the possibility of communication and dialogue becomes increasingly remote. Currently contemporary thinking tries to reach a more “moderate” position concerning the possibility of communication. The goal, however can only be achieved either by attempting a synthesis between the two conflicting poles (nature vs. freedom) of the humanist ground motive, or by suppressing the “claims” of the freedom-pole altogether. As both alternatives are quite unlikely to produce satisfactory solutions, the suggestions of a Dooyeweerdian approach should be taken into account as a possible alternative.

As far as the accounting sciences are concerned, applying the modal aspects of Dooyeweerd, with its attributes of multiplicity and interconnectedness will definitely make room to increase the commonality between the preparer and the user as a prerequisite for conveying meaning in corporate annual reports of companies.

23

BIBLIOGRAPHY

BAUDRILLARD, J. 1984. The ecstacy of communication. ( In Foster, H., ed. Postmodern culture.

London: Pluto. P. 126-134.)

BASDEN, A. & BURKE, M.E. 2004. Towards a philosophical understanding of documentation: a

Dooyeweerdian framework. Journal of Documentation. 60 (4):352-370.

BASDEN, A. 2011. A presentation of Herman Dooyeweerd’s aspects of temporal reality.

International Journal of Multi Aspectual Practice 1:1-28.

COLETTO, R. 2007. The legitimacy crisis of science in late-modern philosophy: towards a reformational response. Potchefstroom: North-West University. (Ph.D. thesis.)

COLETTO, R. 2008. When the ‘paradigms’ differ: scientific communications between scepticism and hope in recent philosophy of science. Koers, 73(3): 445-467.

CR ONJé, C. 2008. Corporate Annual Reports (CARS): Accounting practices in transition.

Saarbrüken, Germany: VDM Verlag Dr Müller.

CRONJ

é, C.J. & GOUWS, D.G. 2011. Commonality between the preparer and the user of financial information as a prerequisite for conveying meaning. South African Business Review,

15(2):43-58.

CRONJ

é, C.J. 2012. The migration of financial reporting practices: From positivism to relativism.

Potchefstroom: North-West university. (Unpublished assignment.)

DOOYEWEERD, H. 1984. A new critique of theoretical thought 4 volumes. Jordan Station,

Ontario, Canada: Paideia Press. (Original work published 1953-1958)

FEYERABEND, P.K. 1975. Against method: outline of an anarchistic theory of knowledge.

London: New Left Books.

KUHN, T.S. 1970a. The structure of scientific revolutions. Chicago: The University of Chicago

Press.

KUHN, T.S. 1970b. Reflections on my critics. ( In Lakatos, I. & Musgrave, A., eds. Criticism and the growth of knowledge. Cambridge: Cambridge Universty Press. P.231-277.)

KUHN, T.S. 1979. Metaphor in science. ( In Ortony A., ed. Metaphor and thought. Cambridge:

Cambridge University Press. P. 409-419.)

KUHN, T.S. 2000. The road since structure: philosophical essays 1970-1993. Chicago: University

24

of Chicago Press.

LYOTARD, J.-F. 1984. The postmodern condition: a report on knowledge. Manchester:

Manchester University Press.

POLANYI, M. 1958. Personal knowledge: towards a post-critical philosophy. London: Routledge

& Kegan Paul.

POPPER, K.R. 1963. Conjectures and refutations: the growth of scientific knowledge. Londen:

Rutledge & Kegan Paul.

POPPER, K.R. 1970. Normal science and its dangers. ( In Lakatos I. & Musgrave A., eds.

Criticism and the growth of knowledge. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. P. 51-58.)

25