Conceptualising and measuring agency using the British Household

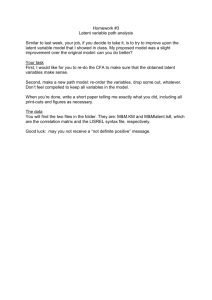

advertisement

Paul Lambe School of Education and Lifelong Learning St Luke’s Campus Heavitree Road University of Exeter Exeter p.j.lambe@exeter.ac.uk Conceptualising and measuring agency using the British Household Panel Survey A paper presented at the BERA Annual Conference 6-9 September 2006, University of Warwick, This working paper was produced as part of the Learning Lives Project*. Copyright lies with the author. If you cite or quote, please be sensitive to the fact that this is work in progress *The Learning Lives: Learning, Identity and Agency project (see learninglives.org) is a collaboration between the Universities of Exeter, Brighton, Leeds and Stirling and is funded by the Economic and Social Research Council as part of their Teaching and Learning Research Programme (TLRP) see www.tlrp.org Conceptualising and measuring agency using the British Household Panel Survey Introduction The concept of agency is of central concern to the Learning Lives project. The project aims to understand the relationship between adult learning and agency over the life course in terms of how learning impacts on agency and, conversely, how agency impacts on learning. The project approaches learning as one of the ways in which people respond to events in their lives, often to gain more control over their lives. To further these aims it is necessary to critically evaluate whether empirical evidence supports or disputes theoretical connections between agency and adult learning. However, as outlined below, agency is a rather broad and elusive latent concept. This paper takes a preliminary step in this direction as its purpose is to characterise one major aspect of the self’s agency, self-efficacy, using items (questions) from the British Household Panel Study1 (BHPS). Furthermore, this paper illustrates the application of Latent Class Analysis, a powerful new tool in the analysis of typologies and scale response patterns from categorically scored survey data using the LEM 2 software programme. Theorisation of Agency In recent years much valuable theoretical writing has appeared that has increased our understanding of agency (Yoder 2000, see Cote and Levine 2002 for a review of the psychological and sociological literature, see Emirbayer and Mische 1998 for a review of literature theorising agency). Nevertheless, the concept of agency, as the following brief review of literature points up, has maintained an ‘elusive… vagueness’ (Emirbayer and Mische 1998:962). Karen Evans, has identified 12 factors of importance in the analysis of ‘bounded’ agency and control :- sociability, confidence, fulfilled work life and fulfilled personal life, belief that opportunities are open to all, belief that own weaknesses matter, belief in planning not chance, belief that ability not rewarded, active career seeking, unlikely to move, politically active, helping/people career oriented, and negative view of future (Evans 2002:255). John 1 The British Household Panel Survey (BHPS), started in 1991, is conducted by the ESRC UK Longitudinal Studies Centre together with the Institute for Social and Economic Research at the University of Essex. The BHPS was designed as an annual survey of each adult (16+) member of a nationally representative sample of more than 5,000 households, making a total of approximately 10,000 individual interviews. The same individuals are re-interviewed in successive waves and, if they split off from original households, all adult members of their new household s are also interviewed. Children are interviewed once they reach the age of 16; there is also a special survey of 11-15 year old household members from wave 4 onwards (1994). Thus the sample should remain broadly representative of the population of Britain as it changed through the 1990s and beyond. At wave 9 (2000) two additional samples to the BHPS in Scotland and Wales were added thus permitting independent analyses of these countries and comparative analysis with England. At wave 11 (2002) an additional sample from Northern Ireland was added to increase the representivity of the whole of the United Kingdom. Documentation and questionnaires available at www.iser.essex.ac.uk/ulsc/bhps 2 LEM : A general programme for the analysis of categorical data, (log linear and event history analysis with missing data using the EM algorithm. See http>//spitswww.uvt.nl/~vermunt 1 Bynner sees personal agency as comprised of an individual’s disposition (sense of self-efficacy, sense of internal locus of control, motivation, aspiration and selfesteem) and resources (social, cultural, human capital), including community resources and an individual’s membership of, and activity in community/civic organisations which may enhance an individual’s social and human capital and improve that individual’s prospects and indeed, sense of agency (Bynner 2001:23). Yaojun Li, Andrew Pickles and Mike Savage, using BHPS data, have taken a more nuanced view and have broken down the concept of social capital into three distinct dimensions; ‘civic participation, social networks and neighbourhood attachments’, and argue that ‘civic participation is just one out of a range of channels of social capital generation’ and that more ‘informal networks affect people’s attitudes, values, preferences and key aspects of their life-chances’ (Li et al 2003:16). Emirbayer and Mishe comment that the concept of agency has been associated with, inter alia, motivation, will, sense of purpose, intentionality, choice, initiative, and goal seeking (Emirbayer and Mische 1998). Whilst Cote and Levine’s construct, identity capital, cites agency residing in and emanating from tangible personal assets such as memberships of organisations, and intangible personal assets such as internal locus of control, self-esteem, self-efficacy, a sense of purpose in life, the ability to selfactualise and ideological commitment which ‘combine to predict identity capital in terms of formulating a stronger sense of adult identity’ (Cote and Levine 2002:143149). Gert Biesta and Mike Tedder have conceptualised agency not as an ‘individual possession but something that is achieved in action’ which they argue calls for ‘an ecological understanding of agency’ (Biesta and Tedder 2006). Like Emirbayer and Mishe, they contend that individuals, influenced by past achievements, understandings and patterns of action, who are motivated to realise a future that is different from their past, can only act out this intention in the present, or plan for the future. Thus in a context in which each individual’s capacity to make ‘practical and normative judgements among alternative possible trajectories of action [is conditioned by the] emerging demands, dilemmas and ambiguities of presently evolving situations’(Emirbayer and Mishe 1998, quoted by Biesta and Tedder 2006). Their emphasis on changing contexts-for-action over time raises fundamental questions about the relationship between agency and learning in the life course. Not least : why individual’s can be agentic in one situation and not another, why an individual’s capacity for agentic behaviour can change over the life course, and what are the catalysts that initiate the learning processes which enable people to reconstruct their agentic orientations. At the same time Biesta and Tedder emphasise that ‘agentic orientations … are never sufficient to understand actual agency … because [direction of one’s life] … also depends on contextual and “ecological” factors and on available resources within a particular ecology’( ibid: p9). One of the principal tenets of life course theory is the significance of human agency in life course construction and at the core of human agency is the self, or self-agency (Elder, 1974, 1995, Gecas 2004:369, Badura 1997:3). Self-agency underpins Bandura’s theory of self-efficacy, indeed ‘efficacy belief [is regarded as]… a major basis of action’ and Bandura defines perceived self-efficacy as ‘not a measure of the skills one has but a belief about what one can do under different sets of conditions with whatever skills one possesses’ (Bandura 1997:37). Gecas defines self-efficacy as referring to the ‘perception of oneself as a causal agent in one’s environment, as 2 having some control over one’s circumstances , and being capable of carrying out actions to produce intended effects’ (Gecas 2004, 370). There is much evidence of the relationship between an individual’s self-efficacy and their functioning and wellbeing in the domains of academic achievement, occupational achievement, and general physical and mental well-being (see Bandura 1997, Swartzer and Fuchs 1996, ). Indeed, Gecas argues that those with ‘high self-efficacy, especially in such domains as education, inter-personal relations, and occupational contexts, are more likely to be the architects of their own lives and to see themselves as such’, and that the converse is more likely for those with low self-efficacy (Gecas 2004:370). Furthermore, in relation to adult learning recent studies suggest that participation in adult learning has a positive effect upon self-efficacy (Schuller et al 2002, Hammond and Feinstein 2005).Clearly, self-efficacy, an individual’s belief in his or her own efficacy and personal control, is an important facet of the latent concept agency and major influence upon life course construction. This brief review of the theorisation of agency points up that it is crucial to locate learning and agency in a temporal framework in order to examine their dynamic qualities and the changing influences upon them. Furthermore, that the characterisation of a measure of self-efficacy in isolation from contextual effects emanating from various sources including those of social capital generation will allow us to control for and test hypotheses concerning the effects upon this key element of agency of changing contextual influences, thereby moving us towards an ecological understanding of agency. This necessitates longitudinal analysis of panel data such as the BHPS. However our immediate concern is an analysis using items from a single wave of the BHPS to characterise the latent concept self-efficacy and examine its relationship with adult learning. Methodology Much of previous research into agency, has employed factor analysis of survey items to reduce many observed variables to only a few latent factors, and respondents’ predicted factor scores then used in post hoc analysis of the relationship between agency and learning ( Evans 2002, Cote 1997, Li et al 2003, Hammond and Feinstein 2005). It is the case that the vast majority of variables in the most widely used social science data sets, including the BHPS are scored as categorical data, either nominal or ordinal. Clearly, when possible, it is preferable to select analytic techniques that conform to the requirements of both the theoretical concept of interest and the nature of the measures of the data available. For these reasons Latent Class Analysis (LCA) is used here. LCA is a statistical method for studying categorically scored variables that does not require data to meet the assumptions of multivariate normality and continuity of measurement, and is eminently suited for life course analysis using categorically scored survey data. It provides a powerful new tool in the analysis of typologies (classes), either as a method for empirically characterising a set of latent types within a set of observed indicators or as a method for testing whether a theoretically posited typology adequately represents the data. LCA can be considered as a ‘qualitative data analogue to factor analysis. It enables researchers to empirically identify discrete latent variables [ e.g agency, religious commitment] from two or more discrete [categorical] observed variables’ ( McCutcheon 1987:7, McCutcheon and Mills 1998, Vermunt, 1997a). Indeed recent developments allow analysts to include variables of mixed type (nominal, ordinal, continuous/and or count variables) 3 in the same analysis. LCA is a flexible methodology that enables researchers: to identify a set of mutually exclusive latent classes, or typologies, from observed categorically scored survey data, and thus empirically characterise typological classifications (multidimensional). It also enables researchers to analyse the scalability of a set of observed categorical items into ordinal measures of a latent variable, and additionally allows us to discern whether the defined latent variable ( e.g. self-efficacy) is invariant over multiple populations (i.e. comparative analysis of scale characteristics and typologies in different populations, social groups. Furthermore, models for the analysis of categorically scored panel data allow us to examine and test formal hypotheses about the nature of change in scale characteristics and typologies identified using identical measures at different times for the same population (passim McCut cheon 1987, see also McCutcheon 1996, Macmillan and Eliason 2004, Vermunt 1997b). Hence, the appropriateness of LCA for examining the relationship between adult learning and self-efficacy over the life course using panel data such as the BHPS. At BHPS wave 11 (2001) a block of items, CASP-19 (a 19 item Likert scaled index measuring quality of life), was included as a core rotating component ( CASP-19 will be included again at wave 16). CASP-19 was originally developed as a measure of quality of life in early older age and specifically designed to exclude ‘contextual and individual phenomena that might influence it, such as health, social networks, and material circumstances’ and specifically designed to tap into the agency of older people (Hyde et al 2003:187). The CASP19 scale has been used in the English Longitudinal Study of Ageing, the UK Whitehall Study, the US Health and Retirement Study and a shorter version in the Study of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe. A raft of studies have validated this measure3, and its development is outlined in Hyde et al 20034. However the BHPS is the first survey to use the scale on its whole sample of respondents at all ages because of its proven reliability and validity. The items in the CASP-19 scale (see Table 1 below) tap four domains: control, autonomy, self realisation and pleasure. Clearly, as intended by its authors, in the three domains of control, autonomy and self-realisation the items tap in to sense of agency and self-efficacy as theorised by Bandura , and empirically evidenced by Evans, Bynner, Cote and Levine, Emirbayer and Mische. The inclusion of CASP-19 in the BHPS as a core rotating component will no doubt prove to be an extremely useful resource in longitudinal educational research as an instrument to measure sense of agency and its relationship with learning over time, albeit an instrument whose data collection points are at five yearly intervals. However, what is required for our purposes is an equivalent instrument whose data are recorded in the smallest possible units of time, and in the case of the BHPS this would be at each annual wave. Fortunately, at all waves of the BHPS since 1991 onwards a General Health Questionnaire has been included, and along with other BHPS core questions we are able to construct an instrument whose items approximate those used in the domains of control, autonomy and self-realisation of CASP-19. Table 2 below outlines these core BHPS items and their counterparts in CASP-19. 3 See www1.imperial.ac.uk/medicine/people/d.blane for an extensive list of publications by Professor David Blane, Department of Medecine, Imperial College. 4 See Hyde, M., Wiggins, R.D., Higgs, P., and Blane, D., (2003) A measure of quality of life in early old age : the theory development and properties of a needs satisfaction model (CASP-19), pp 186-194 in Aging and Mental Health, 7, (3). 4 Table 1:Item wording and domains for CASP-19 Each item has the response categories coded as follows, Often =3, Not Often=2, Sometimes =1, and Never=0. CONTROL AUTONOMY PLEASURE SELFREALISATION My age prevents me from doing the things I would like to I feel that what happens to me is out of my control I feel free to plan for the future I feel left out of things I can do the things that I want to do Family responsibilities prevent me from doing what I want to do I feel that I can please myself what I can do My health stops me from doing the things I want to do Shortage of money stops me from doing the things I want to do I look forward to each day I feel that my life has meaning I enjoy the things that I do I enjoy being in the company of others On balance I look back on my life with a sense of happiness I feel full of energy these days I choose to do things I have never done before I feel satisfied with the way my life has turned out I feel that life is full of opportunities I feel that the future looks good for me 5 Table 2: BHPS proxy items and their CASP-19 counterparts ( excludes item 1 My age prevents me from doing the things I would like to). The emboldened items in the CASP-19 column form the eight item version. The BHPS items which appear at all waves, KGHQC-L, KHLLT( *** this item does not appear at waves I and n of the BHPS, however values at preceding and consecutive waves allow imputation of missing values), KFISITX, reverse coded where necessary and dichotomised. BHPS items all waves Have you recently been able to face up to problems ? (Item KGHQF) Domain CASP-19 items I feel that what happens to me is out of my control * CONTROL I feel free to plan for the future I feel left out of things* ( Item KQLFD) Have you recently felt you are playing a useful part in things? ( Item KGHQC) I can do the things that I want to do * Have you recently been losing confidence? (Item KGHQJ) AUTONOMY Family responsibilities prevent me from doing what I want to do I feel that I can please myself what I can do* ************************* Have you recently felt capable of making decisions about things? (Item KGHQD) Does your health in any way limit your daily activities compared to most people of your age? ( Item KHLLT)*** My health stops me from doing the things I want to do* How well would you say you were managing financially? (Item KFISIT) Have you recently been able to enjoy your normal day to day activities (Item KGHQG) Have you recently felt constantly under strain? (Item KGHQE) *********************** Shortage of money stops me from doing the things I want to do Have you recently been feeling reasonably happy all things considered? (Item KGHQL) Have you recently been thinking of yourself as a worthless person? (Item KGHQK) Looking ahead how do you think you will be financially a year from now? (Item KFISITX) I look forward to each day I feel full of energy these days SELF-REALISATION I choose to do things I have never done before I feel satisfied with the way my life has turned out* I feel that life is full of opportunities* I feel that the future looks good for me* Analysis: Part 1 6 Our sample comprised 5,718 adults of working age (BHPS wave 11, England only) females aged 16-59 years and males aged 16-64. Firstly, all CASP-19 items in the domains of CONTROL, AUTONOMY and SELF REALISATION were subject to LCA and a more parsimonious seven-item shorter version derived (see Table 2, the emboldened items in the CASP-19 column, recoded 1 for a non -agentic response and 2 for an agentic response) . Latent class analysis of the seven-item CASP scale produced a two class model which assigned cases into two distinct typologies. Class 1 in which there was a very high probability of an agentic response to each of the seven items and class two in which respondents had very low probability of an agentic response to each item. Table 3 below outlines the conditional probabilities of an agentic response to the items in the scale and the Latent Class probabilities, that is, the probability of a respondent belonging in either the agentic or non-agentic group given their responses to the shortened seven-item CASP instrument. Eighty percent of respondents were classified as agentic. Thus 8 in 10 of our sample are typified as having a positive perception of their self-efficacy, and two in ten of the sample as having a much poorer perception of their self-efficacy. Clearly, as the CASP-19 was designed specifically to tap into sense of agency and is a much validated instrument in its entirety and in its shortened versions, these findings come as no surprise Nevertheless, the analysis confirms that our seven- item version is a valid measure of self-efficacy. The next step in the analysis was to examine the relationship between the seven-item version of CASP-19 and variables shown to have an effect on the likelihood of low self-efficacy and thereby test its external validity. Respondent’s employment status was added to the above model as a grouping variable and the null- hypothesis tested that it would have no effect upon the probability of a respondent being assigned to either of our two latent classes of self-efficacy. The conditional probability of an unemployed respondent being assigned to the non-agentic latent class,(ie. those with a poor perception of self-efficacy) was .8759, and the conditional probability of being unemployed and being assigned to the agentic latent class a mere 0.1241. Thus the null- hypothesis was rejected, and evidence shown that the relationship between our grouping variable, employment status and each of our indicator variables ( items in the instrument) are mediated through the latent concept self-efficacy. Clearly, being unemployed has a significant impact upon self-efficacy. Similarly a grouping variable, academic qualifications was added to the model (no qualifications or CSE=1, O-level or above=2) and the null- hypothesis tested that it would have no effect upon the probability of a respondent being assigned to either of our two latent classes of self-efficacy. The analysis revealed a conditional probability of .7898 of a respondent being in the agentic latent class for those with O-level or above academic qualifications, and a conditional probability of .2202 of being in the agentic class given a respondent had no qualifications or CSEs. Thus, the null- hypothesis was rejected, and evidence shown that the relationship between our grouping variable, academic qualification, and each of our indicator variables (items in the instrument) are mediated through the latent concept self-efficacy. So far in this paper it has been shown that LCA has great potential to unravel the associations between learning and self-efficacy. However, what is needed is an equivalent instrument to the seven-item CASP scale, one that is comprised of items which appear at each wave of the BHPS and which can be shown to be measuring the same underlying latent concept. Such an instrument would enable the relationships between learning and self-efficacy to be examined over time and the full potential of 7 the BHPS to be mined. It is this task that the next part of the analysis turns its attention. Table 3: Probability of an agentic response expressing self-efficacy and the Latent Class Probabilities for the two-class model, (n=5,718). Observed Respondent Type CASP -Variables A B C D E F G Relative Class Frequency Agentic .7893 .7983 .9412 .8416 .8517 .9813 .9427 Non-agentic .2107 .2017 .0588 .1584 .1483 .0187 .0573 .8019 .1981 Analysis: Part 2 The aim of the analyses presented in this section is to create an instrument to measure self-efficacy using the proxy items that appear at all waves of the BHPS (emboldened items in first column of Table 2) and evidence that these items are measuring the same underlying concept as their counterparts in the seven- item scale derived from the validated CASP-19 measure of sense of agency. To do this, individually each of the proxy items is added to the seven-class CASP model and an equality restriction is imposed on the conditional probabilities. In this way a parallel indicators hypothesis can be tested by imposing a restriction on the model that the proxy item is a parallel indicator of its counterpart in the seven- item CASP scale, i.e. that they are both measuring the same thing and that the conditional probability of a respondent being assigned to class 1 or class2 of our latent concept self-agency in response to either indicator, at either level of each indicator, agentic or non-agentic, is the same. When testing a parallel indicator hypothesis what we are saying is that two of our indicator variables in the model have identical error rates with respect to each of the latent classes of self-efficacy. This can best be illuminated by an equation: where π is the conditional probability, B is an indicator from the seven-item CASP derived instrument and B1 and B2 its two categories, non-agentic and agentic responses respectively, C is a proxy item from the BHPS which appears at all waves and C1 and C2 are respectively the non-agentic and agentic responses, X 1 is the non-agentic level (class 1) of the latent concept selfefficacy, X2 is the agentic level (class 2) of the latent concept self-efficacy, π B1\X1 = π C1\X1 and π B2\X2 = π C2\X2 For example we hypothesised that proxy BHPS item KGHQC (Have you recently felt you are playing a useful part in things?) is a parallel indicator of KQLFC (I feel left 8 out of things). Parallel hypothesis tests were carried out for all the proxy items and their corresponding items from the validated seven-item CASP scale. Two goodness of fit statistics allow us to evaluate the nearness of our models to the actual observed data., the Pearson Chi square and the Likelihood ratio chi square. When using the seven- item CASP scale with the addition of a proxy indicator as a base model, the restricted model imposing the hypothesis of parallel indicators becomes a nested model and thus we can use the conditional likelihood ratio X- square test to examine whether the newly imposed restriction is acceptable, or whether the restriction results in an unacceptable erosion of fit to the observed data. In all cases we were able to accept our proxy items as parallel indicators of the seven- items derived from analysis of the CASP-19 scale, albeit with some erosion of fit between the models and the observed data. Thus in the next section we are able to test our new seven- item selfefficacy scale to see if latent class analysis results in respondents being assigned with an acceptable level of probability to two distinct levels of the latent concept selfefficacy. Analysis: Part 3 In this section the results of a latent class analysis of the proxy indicators of our latent concept self-efficacy are presented. The items in scale are, KGHQF, KGHQC, KGHQJ, KGHQD, KHLLT, KGHQL, and KGHQK (the questions asked are outlined in the first column of Table 2 above). Latent class analysis of the proxy items scale produced a two class model which assigned cases into two distinct typologies. Class 1, in which there was a very high probability of an agentic response to the sevenproxy items and class two in which respondents had very low probability of an agentic response to each item . Table 4 below outlines the conditional probabilities of an agentic response to the items in the scale, and also the Latent Class probabilities i.e. the probability of a respondent belonging in either the agentic or non-agentic group given their responses to the shortened seven-item proxy instrument. Some 85% of respondents in the sample were classified as agentic and 15% as having a poorer perception of their self-efficacy. These findings are very much in line with those of the seven- item shortened version of the validated CASP-19 instrument. Table: 4: Probability of an agentic response expressing self-efficacy and the Latent Class Probabilities for the two-class model using BHPS proxy items (n=5,718). Observed KGHQF KGHQC KGHQJ KGHQD KHLLT KGHQL KGHQK Relative Class Frequency Respondent Type Agentic .9422 .9684 .9696 .9840 .9091 .9476 .9964 .8526 Non-agentic .0578 .0316 .0304 .0160 .0909 .0524 .0036 .1474 Analysis: Part 4 9 Clearly the seven-item scale derived from proxy indicators included in the BHPS at all waves is measuring the same underlying latent concept as the validated CASP scale, i.e. self-efficacy. Nevertheless it is still necessary to test this new seven-item instrument for external validity. To do this a representative sample of 1393 English respondents aged 20 to 30 years old respondents from wave 11 of the BHPS was analysed using their responses to seven-item scale and including the two indicators employment status and academic qualifications. The results of this analysis clearly evidence that the new seven item instrument assigns respondents in the sample to two definite classes, or typologies of selfefficacy, and that once again employment status and academic qualification are significant indicators in the probability of being assigned to the agentic class of respondents with a positive sense of agency or self-efficacy or to the class of respondents with a poorer perception of their self-efficacy. Table:5 below outlines the LCA two-class model of self-efficacy i.e. the conditional probabilities of an agentic response to the items in the scale, and also the Latent Class probabilities. In this sample of 20 to 30 year olds almost 86% of respondents were assigned to the agentic class with a positive perception of their self-efficacy and 14% to the class with a poorer perception of their self-efficacy. Once again those respondents who are employed and with academic qualifications from O-level or above have a much greater likelihood of being in the agentic class, and conversely those who are unemployed or have no academic qualifications/CSE have a very small likelihood of belonging tothe agentic group with a positive self perception of sense of agency. Table 5: Probability of an agentic response expressing self-efficacy and the Latent Class Probabilities for the two-class model using BHPS proxy items and a sample of 20 to 30 year olds derived from wave 11 of the BHPS (n=1393). Observed Respondent Type Agentic Non-agentic KGHQF .9406 .0594 KGHQC .9645 .0355 KGHQJ .9585 .0415 KGHQD .9844 .0156 KHLLT .9607 .0393 KGHQL .9583 .0417 KGHQK .9944 .0056 EMPLOYED .8444 .1556 QUALIFICATION .8250 .1750 Relative Class Frequency 0.8597 0.1403 Conclusions The analyses set out in this paper aimed to develop a measure of self-efficacy using data from a panel study in order that the relationship between learning and this major aspect of agency could be measured over time in changing contexts. Firstly, the CASP-19 instrument which appeared at wave 11 of the BHPS, and which was specifically designed to measure sense of agency was reduced to a shorter version. This new instrument was shown to be an equally good measure of self-efficacy as the original instrument it was derived from. Proxy items corresponding to those in the 10 reduced CASP instrument and which appear at all waves of the BHPS were evidenced to be an effective instrument for measuring self-efficacy. The methodological contribution of this paper is two-fold. Firstly, in the provision of an instrument that will enable researchers to measure self-efficacy over time and thereby disentangle the effects of changing contexts on people’s perceptions of their self-efficacy. Secondly, in illustrating the use of a modern statistical approach to the analysis of categorically scored survey data, which is eminently suited to analysing panel adapt and change over time. The substantive findings of this paper evidence that employment status and academic qualification are important influences upon a person’s sense of agency and these findings point to the importance of adult learning. However, the use of this new instrument will enable researchers to examine the relationships between adult participation in education and training and self-efficacy over the life course using the British Household Panel Survey. The LEM output from all the above analyses and outline of the models evaluation criteria is available on request to the author. The links between adult learners’ capacity to act autonomously, learning and the effects of changing structural contexts over time are complex, a complexity compounded and confounded by disparate experiences, of transitions in social roles, of transitions in dispositions informed by the past and expectations for the future and constrained or facilitated by the present. It is hoped that the methodological contribution of this paper is its illustration of the flexibility and strengths of Latent Class Analysis as tool to untangle this complexity. Bibliography Bartholomew, D,J., de Menzes, L.M., and Tzamourani, P., ‘ Latent Trait and Latent Class Models Applied to Survey Data’ Chapter 21 in Rost, J., and Langeheine, R., (1997) (eds) Applications of Latent Trait and Latent Class Models in the Social Sciences, Waxman. Bauman, Z., (2000) Liquid Modernity, Polity Press. Bandura, A., (1997) Self-efficacy: The exercise of control, Freeman. Bandura, A., (2001) ‘Social cognitive theory: An agentic perspective’, pp 1-26 in Annual Review of Psychology. Baumeister, R.F., (1999) ‘The nature and structure of the self : An overview’, pp1020 in Baumeister, R.F., (ed) The self in social psychology, Psychology Press. Biesta, G., (2005) ‘Transitions through the lifecourse: Analysing the effects of identity, agency and structure’ unpublished summary of TLRP Seminar, University of Exeter, School of Education and Lifelong Learning. Biesta, G., and Tedder, M., (2006) ‘Agency and learning in the lifecourse’ A discussion paper for the Post-Compulsory Education and Lifelong Learning Research Group, School of Education and Lifelong Learning, University of Exeter,( see working paper on agency at www.learninglives.org ). 11 Biesta, G., and Tedder, M., (2006) ‘How is agency possible? Towards an ecological understanding of agency’ University of Exeter,( see working paper on agency at www.learninglives.org ). Blane, D., Higgs,P., Hyde, M., and Wiggins, R. (2004) Life course influences on quality of life in early old age’, pp 2171-2179 in Social Science and Medecine, 2004, 58. British Household Panel Survey : University of Essex, Institute for Social and Economic Research, British Household Panel Survey, Waves 1-13, 1991-2004, Colchester, Essex: UK Data Archive, April 2005, SN 5151. Bynner, J., Butler, N., Ferri, E., Shepherd, P., and Smith, K., (2001) The design and Conduct of the 1999-2000 Surveys of the National Child Development Study and the 1970 British Cohort Study, Centre for Longitudinal Studies: Institute of Education, University of London. Cote, J., (1996) ‘Sociological perspectives on identity formation: the culture-identity link and identity capital’, pp 417-428 in, Journal of Adolescence, 19. Cote, J., (1997) ‘An empirical test of the identity capital model’ pp 577-597 in Journal of Adolescence. Cote, J., (2002) ‘The Role of Identity Capital in the Transition to Adulthood: The Individualisation Thesis Examined’ in Journal of Youth Studies, Vol.,5, No.,2. Cote, J., and Levine, C., (1989) ‘ An empirical test of Erikson’s theory of ego identity formation’, pp 388-415 in Youth and Society, 20. Cote, J., and Levine, C., (1997) ‘Student motivations, learning environment and human capital acquisition: Toward an integrated paradigm of student development’, pp 229-243 in Journal of College Student Development, 38. Cote, J., and Levine, C., (2002) Identity Formation, Agency and Culture: A Social Psychological Synthesis, Lawrence Erlbaum. Elder, G.H. (1974) Children of the Great Depression, Chicago: University of Chicago Press. Elder, G.H. (1995) ‘Life trajectories in changing societies, pp 46-68 in Bandura, A., (ed) Self-efficacy in changing societies, Cambridge University Press. Emirbayer, M., and Mische, A., (1998) ‘What is Agency?’ pp 962-1023 in, American Journal of Sociology, 103. Engel, U., and Reinecke, J., (eds) (1996) Analysis of Change: Advanced techniques in panel data analysis, Walter de Gruyter. Evans, K., (2002) ‘Taking Control of their Lives? Agency in Young Adult Transitions in England and the New Germany’, pp 245-269 in Journal of Youth Studies, Vol.,5, No.,3, 12 Evans, K., and Heinz, W., (1994) (eds) Becoming Adults in England and Germany, Anglo-German Foundation Publications. Gecas, V., and Burke, P., (1995) ‘Self and Identity’, in Cook, K., et al, (eds) Sociological Perspectives on Social Psychology, Alleyn and Bacon. Gecas, V., (2004) ‘Self-Agency and the Life Course’, pp 369-388 in, Mortimer, J., and Shanahan, M., (eds) Handbook of the Life Course, Springer. Giddens, A., (1991) Modernity and Self Identity, Cambridge Polity Press. Hammond, C., and Feinstein, L., ‘ The effects of adult learning on self-efficacy’, pp 265-287 in London Review of Education, Vol. 3, November 2005. Hyde, M., Wiggins, P., and Blane, D.B., (2003) ‘A measure of quality of life in early old age : the theory, development and properties of a needs satisfaction model’ pp 186-194 in Aging and Mental Health, Vol., 7, No., 3. Li, Y., Pickles, A., and Savage, M., ‘Conceptualising and measuring social capital; a new approach’, British Household Panel Survey Conference 2003, Centre for Census and Survey Research, Department of Sociology, Manchester University. Macmillan, R., and Eliason, S., (2004) ‘Characterising the life course as role configurations and pathways’, pp 529-554, in Mortimer, J., and Shanahan, M., (eds), Handbook of the Life Course, Springer. McCutcheon, A., (1987) Latent Class Analysis, Series: Quantitative Applications in the Social Sciences, No., 64, Sage. McCutcheon, A., (1996) ‘Models for the analysis of Categorically scored panel data’ Chapter 2 in Engel, U., and Reinecke, J., (eds) (1996) Analysis of Change: Advanced techniques in panel data analysis, Walter de Gruyter. McCutcheon, A., and Mills, C., (1998) ‘Categorical Data Analysis: Log-Linear and Latent Class Models’ pp 71-93 in Scarborough, E., and Tanenbaum, E., Research Strategies in the Social Sciences: A Guide to New Approaches, Oxford University Press. Mortimer, J.T., and Lorence, J., (2004) Handbook of the Life Course, Springer. Rost, J., and Langeheine, R., (1997) (eds) Applications of Latent Trait and Latent Class Models in the Social Sciences, Schuller, T., Brasset-Grundy, A., Green, A., Hammond, C., and Preston, J., (2002) Learning continuity and change in adult life , wider benefits of learning, research report no.3, London Centre for Research on the Wider Benefits of Learning. Swartzer, R., and Fuchs, R., (1996) Self-efficacy and health behaviours, pp 163-196 in Conner, M and Norman, P., (eds) Predicting Health Behaviour, Open University. 13 Vermunt, J. K., (1997 a) LEM : A general programme for the analysis of categorical data, user’s manual, University of Tilburg, Nederlands. Vermunt, J. K., (1997 b) Log linear models for event histories, Sage Yoder, A., (2000) ‘Barriers to ego identity status formation: a contextual qualification of Marcia’s identity status paradigm’, pp 95-106 in, Journal of Adolescence, 23. Appendix 1 See Fayers, Book review of Item Response Theory for Psychologists, by Embretson, S.E. and Reise, S. pp 715-716 in Quality of Life Research 13, 2004. IRT advantages: item selection, scale shortening using multi-item scales to evaluate latent concepts, estimates probability of individual’s response to an item will lie in a particular category. Disadvantages: specialist and not user-friendly software, poorly documented, different software programmes produce different results same data, difficult to use statistical goodness-of-fit methods to compare the various models produced, little theoretical research re sample size effects, small number of outliers disproportionately affect model fit. 14