JUSTICE AND MORALITY

advertisement

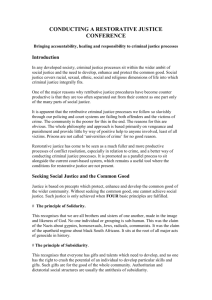

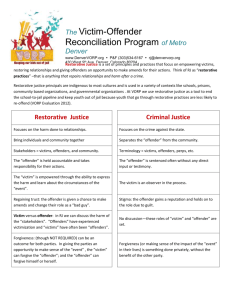

JUSTICE AND MORALITY Delivered byLeela Ramdeen at the Opening of the National Consultation on 'Mediation', 2001. We need to acknowledge that the context in which this national consultation on 'Mediation' is taking place is one in which we are not seeing much, if any, improvement in the crime situation in TT today. My neighbour said to me recently that he is now afraid to read the newspapers as he does not know what will ‘hit him’ next, as far as crime is concerned. Regular kidnapping was something that occurred abroad, in some distant land. A child with a machine gun in a school was alien to us. Today there is intense public pressure to crack down on crime - to introduce more repressive and punitive sanctions against offenders. And yet, amidst all this, we need to be open to new ways of dealing with crime. Indeed, we must consider other options as our current system is not working. Our prisons are overcrowded and conditions there leave much to be desired. Rehabilitation seems to have failed. In many instances incarceration has not proved to be a deterrent. Recidivism levels are high. There are some who believe that those who are incarcerated for less serious crimes are schooled in prison in the ways of more serious crimes. The most interesting issue highlighted throughout research in Maryland (Prison vs Alternative Sanctions – www.msccsp.org/publications/altrecid.html ) was the concept of a ‘prison school’. As one offender stated: “It’s school here! They have nothing to do but talk about the crime they committed, how they did it, and about connections for further crimes”. This is very provocative because it suggests that putting criminals together, facilitates the criminal thinking process and furthers criminal activities upon release. First-time offenders, instead of becoming rehabilitated, become exposed to new criminal ideas and connections on the ‘outside’ sometimes unknowingly, while ‘in the school’. Another issue that must concern us in TT is a perception by certain members of society that justice in our country is only for those who can afford it and that the ones who generally end up in jail are those at the bottom of the social strata of society - the poor, those who cannot afford bail, those who commit crimes due to social conditions that lead them to believe that that is the only way they can survive. It is said that a nation must take measures to encourage its members along the paths of justice and morality. But a key aspect of justice is the principle of fairness, especially in relation to the administration of the law. At the moment, not all stakeholders feel that they are being treated fairly. Perhaps at this stage, it may be helpful to share with you definitions of morality and justice. Morality can be defined as an informal public system applying to all rational persons, governing behaviour that affects others, and has the lessening of evil or harm as its goal. (Stanford Encyclopaedia of Philosophy). It is important to note also that Government has a moral function – that is, to protect human rights and secure basic justice for all members of society. Society as a whole and in all its diversity is responsible for building up the common good. But it is government’s role to guarantee the minimum conditions that make this rich social activity possible, namely human rights and justice. Can we truly say that there is justice in TT where there is abject poverty in certain areas; where the gap between the haves and the have nots is growing; where adequate health care is sorely lacking; where some people do not have access to basic amenities; where some feel that the concept of equality before the law, for example, remains a constitututional dream for them? Theories of justice have been elaborated by philosophers, political scientists, legal theorists, economists and others. Both Plato and Aristotle regarded justice as the essential virtue enabling humans to live together in harmony. In this wider sense justice is closely linked with morality and ethics. In recent times, many theorists have also been concerned with theories of social justice, which examine the question of poverty and the distribution of resources in a society. Ideas of equality pervade most theories of justice and it is usually accepted that departures from equality are unjust. However, the nature of equality and the grounds for justifying equality are highly controversial. Despite the popular expectation that the law exists to achieve just results and will operate in procedurally just ways, there is ample potential for conflict between legal system, natural law, and morality, which gives rise to difficult questions about the nature and application of justice. I am sure that we all recognise the transcendent value of justice as a human good; that justice should inform and guide moral conduct and that justice and morality are intimately connected. Plato’s position in the “Republic” is that the good life is defined in terms of the moral life. There is, according to him, more to the good life than morality, but it is essential to assign absolute priority to the latter. Although two moral lives may not be equally good, a moral life is always superior to an immoral life, however beneficial the latter may seem to be in other respects. Plato believed that the notion of the Good has those features necessary to inform and guide our actions and also serves to form and instruct our moral character. Currently there exist two perceptions of justice - the broad view of justice – justice for all – justice for the good of society, to create order and so on. And then there is the narrow, punitive view of justice - retributive justice by the criminal justice system meted out to some of those who commit crimes, without systems/structures in place to offer proper reparation, restitution, rehabilitation, or restoration. Both the doing of justice and its theorisings, challenge our power of observing and understanding the society around us, as well as our speculative and evaluating powers. We need to address ourselves to what we mean by justice, embracing in this the meanings we have inherited, but also, and above all, the meaning of those meanings for ourselves in our own society in TT. Part of this process involves a reflection of what is happening in our country today. An honest evaluation of, for example, the high rate of recidivism, may highlight to us the lack of effectiveness of particular sanctions. Indeed, if we are considering the issue of justice and morality, we need to consider the following questions: - Are we clear about the basic purpose of sentencing? Is it meant to rehabilitate and change offender behaviour and to deter others from committing crimes or is the purpose of sentencing to incapacitate, or remove the criminal from society? - Have we really examined the goals and philosophies of each particular sanction? What are we trying to achieve? - Has the Criminal Justice System in TT addressed or recognised fundamental reasons for criminal behaviour? Researchers in Maryland USA, referred to earlier, found that during the interviewing process, the deterrent effect of prison seemed to vanish (Zamble, 1993). Many prisoners felt that prison had not helped them solve the problems related to recidivism or change their attitudes, values, or lifestyles. Moreover, some even suggested that staying in prison was their best remedy against recidivism. This highlights the fact that punishment which denies a modicum of respect to the dignity of the offender as a human being serves no worthwhile purpose in social life, but on the contrary tends to undermine the sense of common humanity on which finally social life must build. A system that ignores the needs of victims and the affected community and excludes them from effective participation in the justice process is also deficient. The use of complementary systems has shown promise in, inter alia, producing cost savings and providing prison bed space for more violent offenders. It is within this context that we are exploring the issue of ‘restorative justice’, to suggest new and more fruitful ways of looking at basic questions concerning justice and morality, and the manner in which they are interrelated. Today the criminal justice system is seen as being purely retributive – literally ‘paying back’, beginning with the classical eye for an eye and tooth for a tooth, retribution that matches the punishment to the crime at an individual level involving the victim and offender. It is suggested that over time, we have changed the object of the payback from the victim to the state. Virtually every crime hurts an individual or a community, but we have today made the state the victim instead of its people as individuals or collections of individuals (communities). In today’s justice system, both the injured party and the offender only serve the state in its need for a payback. State interests drive the process of doing justice. Prof. Howard Zehr, one of the leading proponents of restorative justice, states that the working metaphor of the political and legal institution known as the state is the metaphor ‘breaking’. When a law is ‘broken’, we look for the person who ‘broke’ it, and figuratively ‘break’ that person in return. We used to break people on the rack; we now break them in prisons. The institutional system of justice has serious flaws. It claims to make individual accountable for their actions by punishing them. In reality accountability seldom results from the punishments used today. As Zehr stated: ‘In treating itself as the injured party, the institution of the state neglects the personal injuries caused by the crime. It seeks to punish (‘break’) the offender by marginalising that person, stripping him or her of feelings, and removing his or her identity…all by incarcerating that person in close association with others whom it has treated similarly’. Although citizens can turn for retribution to the civil courts, any success they have does not restore wounds to wholeness; the offender remains in the situation out of which the offence came. Education, and forgiveness are absent in both the criminal and civil courts. Accountability and responsibility are present in both forms of justice, but are qualitatively different, affected by the presence or absence of guilt and shame. Powerful and effective community functions of talking circles, dialogue, and mentoring play no role in courtroom proceedings. In many countries, a growing consensus demands restoration of the wound, the hurt, to wholeness. A new form of justice – restorative justice - has begun to appear in our consciousness over the last 25 years or so; a justice that will first involve the persons and their communities in the search for answers that restore relationships and only turns to the state for retribution in specific cases. There is a need for both restorative and retributive justice. This requires root and branch changes in our current system. However, achieving and maintaining a balance between the two is what we should strive for. What we need to do is to repair or restore relationships, personal or communal, damaged by criminal or delinquent acts. This is a challenging goal. The distinction between the paradigm of retributive justice and that of restorative justice has been developed by Zehr. The initial conceptualization of RJ began in the late 1970s and was first clearly articulated by Zehr in 1985.Whereas retributive justice focuses on punishment, the restorative paradigm emphasises accountability, healing and closure. Restorative justice has qualities that challenge our thinking: qualities of diversity, holism and integration, compassion, forgiveness, and love. At this point in time restorative justice lacks a comprehensive plan for broad implementation as a new paradigm to fully replace current systems. It is, therefore, not a cure-all but a powerful complement to the current system. Restorative justice has been described as a paradigm shift of criminal justice; ‘an entirely new framework for understanding and responding to crime and victimisation’ (Umbreit, 1997). It represents a promising new practice theory that is receiving an increasing amount of attention in North America, Europe, Australia, New Zealand and South Africa. In America restorative justice policies and programs are known to be developing in more than 45 states (over 300 communities/programs) where major systemic change is taking place. It is a victim-centred response to crime that provides opportunities for those most directly affected by crime – the victim, the offender, their families, and representatives of the community – to be directly involved in responding to the harm caused by the crime. There is more active involvement in the justice process by all stakeholders in our democratic society. It is based upon a clear set of values and principles which emphasise the importance of providing opportunities for more active involvement in the process of: offering support and assistance to crime victims; holding offenders directly accountable to the people and communities they have violated; restoring the emotional and material losses of victims (to the degree possible); providing a range of opportunities for dialogue and problemsolving among interested crime victims, offenders, families, and other support persons; offering offenders opportunities for competency development and reintegration into productive community life; and strengthening public safety through community building. The principles of restorative justice draw upon the wisdom of many indigenous traditions, including many pre-colonial societies in Africa, Native American, Hawaiian, Canadian First Nation people, Aborigines in Australia, and the Maori in New Zealand. Specific examples of restorative justice include: crime repair crews, victim intervention programs, family group conferencing, victim offender mediation and dialogue, peacemaking circles, victim panels that speak to offenders, sentencing circles, community reparative boards before which offenders appear, offender competency development programs, victim empathy classes for offenders, victim directed and citizen involved community service by the offender, community-based support groups for crime victims, and for offenders. The oldest and most widely developed expression of restorative justice, with more than 25 years of experience and numerous studies in North America and Europe, is victim offender mediation and dialogue programs. These programs currently work with thousands of cases annually through more than 300 programs throughout the US and more than 900 in Europe and there is a rich resource of empirical data available from these programs. Although there has not been extensive evaluation of the full range of restorative justice policies and practices, research findings so far have found restorative justice programs to have high levels of victim and offender satisfaction with the process and outcome, greater likelihood of successful restitution completion by the offender, reduced fear among victims, and reduced frequency and severity of further criminal behaviour. It is important to note that there are certain ‘fears’ that exist in the minds of some regarding the introduction of restorative justice as a complementary system to that which exist currently. The following are some questions that we may need to address: Will Restorative Justice simply be window dressing in which the Criminal Justice System redefines what has always been done with more professionally acceptable and humane language while not really changing policies and procedures? Is there a danger that only a few pilot projects may be set up on the margins of the system, while the mainstream of business is entirely offender-driven and highly retributive with little victim inv and services, and even less community involvement? If we focus intensely on Restorative Justice interventions , will we be in danger of ignoring the larger issue of the tremendous overuse of costly incarceration. If we fail to address this there will not be the financial resources available to move toward a truly Restorative Justice model. How successful will we be if we seek to introduce a Restorative Justice model without seeking to change also the culture of violence and aggression in our society; a culture in which politicians continue to play the race card, thus dividing the nation, at every opportunity they can simply to win votes from different ethnic groups? Will such a culture facilitate the successful introduction of this model?) I wish to end my contribution by outlining what Prof. Zehr sees as the signposts of restorative justice. We are working toward restorative justice: - - when we focus on the harms of wrongdoing more than the rules that have been broken; when we show equal concern and commitment to victims and offenders, involving them both in the process of justice; when we work toward the restoration of victims, empowering them and responding to their needs as they see them; when we support offenders while encouraging them to understand, accept and carry out their obligations; when re recognise that while obligations may be difficult for offenders, they should not be intended as harms and they must be achievable; when we provide opportunities for dialogue, direct or indirect, between victims and offenders as appropriate; when we involve and empower the affected community through the justice process, and increase their capacity to recognise and respond to community bases of crime; when we encourage collaboration and reintegration rather than coercion and isolation; - when we give attention to the unintended consequences of our actions and programs; and when we show respect to all parties including victims, offenders, and justice colleagues. CRIME WOUNDS – JUSTICE HEALS. Let’s consider how we can change our Justice system to help to heal and build our nation. Thank you.