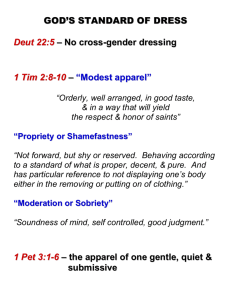

The Dangers of Men in Women`s Roles on Stage:

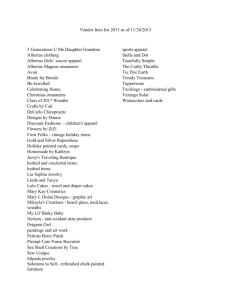

advertisement