SEXUAL HARASSMENT NOTES

(PLEASE NOTE THAT I ELIMINATED FOOTNOTES FOR EASE OF READING - THE

FOLLOWING BORROWS HEAVILY FROM CASES, STATUTES, EEOC GUIDANCES &

ARTICLES. REFERENCES TO CLASS TEXT CASES AND QUESTIONS ARE GIVEN)

Sexual harassment is a form of sex discrimination prohibited by Title VII. There are two distinct

types of sexual harassment recognized under Title VII: “Quid Pro Quo (“Tangible Job Detriment”) and

“hostile work environment”.

A. Overview of two types of sexual harassment

1. Quid Pro Quo/Tangible Job Detriment

“Quid Pro Quo” harassment typically involves an employee whose refusal to submit to a

supervisor’s sexual demands resulted in a tangible job detriment (“tangible employment

action”).

a. tangible employment action A tangible employment action “constitutes a

significant change in employment status, such as hiring, firing, failing to promote,

reassignment with significantly different responsibilities, or a decision causing a

significant change in benefits.”

2. Hostile Work Environment

Discriminatory creation of a hostile work environment is actionable, but the analysis is

more complex. The successful Title VII claim for hostile work environment sexual

harassment requires proof that the hostile environment was created “because of” the sex

of the victim.

a. Severe and pervasive The environment created by unwelcome verbal or

physical conduct of a sexual nature must be sufficiently severe or pervasive to

alter the conditions of employment.

i. duration, frequency, as well as nature and severity of conduct is taken

into consideration in determining whether a hostile work environment

exists. For example, one sexual assault by a co-worker may create a

hostile work environment, but one tasteless joke of a sexual nature told

in the office would not.

The conduct must be “unwelcome” by the victim. A work environment tainted by sexual conduct

that was welcomed by the victim and in which he or she participated does not constitute sexual harassment

under Title VII. Whether the conduct was subjectively “unwelcome” is an issue of fact, meaning that an

investigator and/or a jury must decide this.

Recognizing that employees often quietly tolerate behavior they genuinely find offensive, courts

do not view plaintiff’s acquiescence or “voluntary” participation as necessarily establishing that the victim

welcomed the conduct.

Further, as shown by Meritor Savings Bank v. Vinson (text p. 275), even a consensual sexual

relationship between adult employee and supervisor is not necessarily “welcome” within the meaning of

hostile work environment. Implicit or express pressure to engage in such a relationship given, for example,

the supervisor-employee relation, could lead a factfinder to determine that this relationship was

“unwelcome” by the employee. (Thus, many employers have “no fraternization” policies regarding

supervisory-employee relationships - we will explore this under the topic of “Workplace Privacy.”)

B. Reasonableness Standard in Hostile Work Environment Claims

The conduct creating a “hostile work environment” must be both objectively and subjectively

offensive. The victim must show that he or she subjectively perceived the behavior as abusive. Further, the

conduct must be shown to create an environment that a reasonable person would find hostile or abusive.

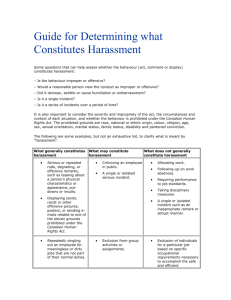

In determining whether conduct is objectively unreasonable, courts recognize that not all conduct

that may be characterized as sexual creates a hostile work environment within the meaning of Title VII. A

single instance of unwelcomed touching, casual flirting, or random physical compliments probably would

not result in a reasonable person finding that working conditions had been adversely affected. However,

repeated requests for a sexual relationship may create a workplace climate that is objectively offensive. The

focus of the reasonableness standard’s application in hostile work environment claims is whether the

reasonable person would agree with the victim that his or her job was made more difficult due to the

conduct in question.

1. Reasonable person/woman/ victim standard:

In Ellison v. Brady (Text p. 285), the “reasonable victim” standard was adopted to analyze

whether the behavior complained of created a hostile work environment. This helps ensure that the

factfinder (e.g. an investigator) considers the situation from the viewpoint of the victim. Thus, a male

investigator of a complaint made by a female would consider the facts from a woman’s vantage point rather

than his own male perspective. While this was not at issue in the case, the decision also would call for a

female investigator to consider the facts from a male’s perspective in a case of a male complainant.

C. Same-Sex Harassment

While California FEHA protects against sexual orientation discrimination in the workplace, Title

VII does not cover sexual orientation discrimination. However, Title VII does protect against

same-sex harassment.

1. Oncale v. Sundowner Offshore Services (text p. 264): In this case, Justice Scalia, writing for

the majority of the U.S. Supreme Court, reminds us that sexual harassment is a form of gender

discrimination that protects both men and women. The Court had rejected the presumption that an

employer would not discriminate against his own race in employment. Similarly, the Court would not

presume that men could not discriminate against men, or women against women. Thus, since harassment is

a form of discrimination, it follows that men could sexually harass men and women could sexually harass

women at work in violation of Title VII.

a. What is not sexual harassment: Justice Scalia also set forth that ordinary horseplay

or mild office flirtation is not what is meant by “sexual harassment.” Rather, Title VII protects against

conduct that is so objectively offensive that the terms and conditions of employment are altered for the

victim because of his or her gender.

b. How to draw the inference of discrimination in a same-sex harassment case:

Proof of discriminatory intent in same-sex harassment (proof that the victim is suffering adverse terms and

conditions of employment because of his or her gender) could be offered in the following ways:

1. homosexual desire

2. General hostility to the presence of the victim’s gender in the workplace (e.g.

a male physician shows hostility towards male nurses)

3. Comparative evidence on the difference between how the harasser treats the

two genders in the workplace. (i.e. “equal opportunity harassers” may escape Title VII liability).

D. Employers’ Liability and the Affirmative Defense

Employers covered by Title VII face liability for the sexual harassment of their employees.

1. Co-Worker Harassment: Under both California’s FEHA and Title VII, liability for the

harassing conduct of co-workers is limited to employers’ negligence: If an employer knows or should have

known of the questionable conduct by failed to respond adequately to correct it, then the employer faces

liability for the co-worker’s harassment.

2. Supervisory Harassment: Supervisory harassment places a higher level of liability on the

employer: the supervisor’s position of authority within the employer’s organization makes his or her acts

attributable to the employer. Thus, the employer is “vicariously liable” for the actions of the supervisor.

What if the employer is unaware of the supervisor’s conduct?

In two 1998 decisions, the United States Supreme Court addressed the issue of employers’

vicarious liability for supervisory harassment. In Burlington Industries, Inc. v. Ellerth and Faragher v. City

of Boca Raton,(text p. 291) the Court distinguished between supervisory harassment resulting in a tangible

job detriment, and a hostile work environment created by a supervisor that did not lead to a tangible

employment action.

a. Strict Liability for supervisory harassment - tangible job detriment: An employer

is “strictly liable” for supervisory harassment resulting a tangible job detriment such as termination or

demotion, regardless of whether it was aware of the supervisor’s actions. This means that the employer is

liable for injuries caused by the supervisor’s harassment regardless of whether or not the employer was

aware of the supervisor’s conduct.

If this seems harsh, consider the situation: an employer has placed a supervisor in a position

where he or she can abuse their power - and the supervisor has done so.

b. Strict Liability for supervisory harassment not resulting in a tangible job

detriment - affirmative defense available:

When no tangible employment action resulted from the supervisor’s harassment, the employer may raise an

affirmative defense.

The affirmative defense available to employers facing liability for supervisory harassment that did

not result in a tangible job detriment has two requirements.

i. Basic requirements of the affirmative defense:

1. First, the employer must have exercised reasonable care to prevent

and correct promptly any sexually harassing behavior.

2. Second, either the plaintiff employee unreasonably failed to take

advantage of any preventive or corrective opportunities provided by the

employer, or the employer took prompt and effective action after the

employee availed himself or herself of the employer’s anti-harassment

policy and procedure.

Therefore, to preserve the affirmative defense against strict liability for supervisory harassment,

employers must properly communicate a written anti-harassment policy and offer effective mechanisms for

reporting and resolving complaints. Once a complaint is made, the employer must undertake a prompt and

effective investigation and effectively remedy any harassment it discloses.

ii. California FEHA does not recognize affirmative defense

The California Court of Appeal has rejected the application of the affirmative defense in a

supervisory harassment case brought under California FEHA. This does not mean California employers

should ignore the need for training, policies, and investigations. All these measures can help prevent

harassment from occurring, or at least avoid litigation arising from it. (A victim who gains relief from the

employer will not be likely to make a complaint with the Department of Fair Employment and Housing).

PLEASE REFER TO THE CLASSROOM HANDOUT ON “PRESERVING THE AFFIRMATIVE

DEFENSE” FOR THE GUIDANCE ON CREATION OF POLICIES AND REPORTING SYSTEMS, AND

ON EFFECTIVE INVESTIGATIONS.

E. OTHER TYPES OF LIABILITY FROM WORKPLACE SEXUAL

CONDUCT:

Employees can sue employers for personal injury such as defamation, assault and

battery, invasion of privacy, and intentional infliction of emotional distress, without

making a statutory claim of sexual harassment.

G. ANSWERS TO CHAPTER 8 CHAPTER-END QUESTIONS:

1. No. Not without more. There is no indication that the activity is unwelcome,

severe, or pervasive.

2. Probably not. The court said that this is not the type of situation that would

unreasonably interfere with the employee’s work performance.

3. Not without more - this does not appear to be severe or pervasive conduct.

4. Probably not. The key facts are that the ex-boyfriend has left her alone and that

he does not appear to have any supervisory authority over her.

5. Probably not without more.

6. Yes - if the requirements are present.

7. The court determined that, while the joke was in poor taste, severity and

pervasiveness was absent.

8. Margaret could bring a claim for sexual harassment under Title VII - the fact

that the alleged harasser is also female does not bar such a claim.

9. Trick question - this is not an employer-employee relationship.

10. Pat should immediately investigate the claim using the handout you received

in class on preserving the affirmative defense, of course! Even in a case of co-worker

harassment, a prompt and effective investigation is necessary, especially since the

employer now “knows or should know” of the concern because Trudy has complained to

Pat the supervisor.