Analytic of Equity - Columbia Law School

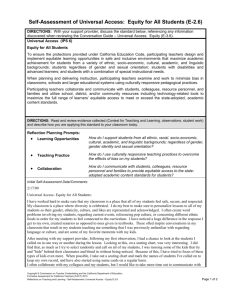

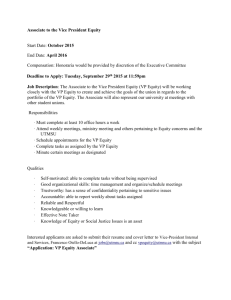

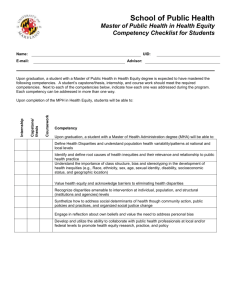

advertisement