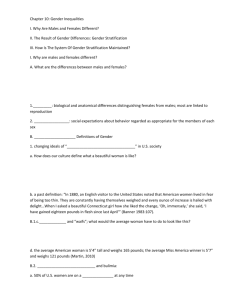

Structure of the Education System

advertisement