פרשת שופטים

advertisement

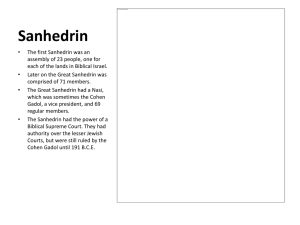

פרשת שופטים We know that machlokes, dispute, is anathema to 'Am Yisroel. In fact, there is a mussar admonishment that is based on a Posuk at the beginning of our Parsha. We are told that the ultimate resolution of Halachic disputes should find their venue in the Beis Din HaGodol that sat in one of the chambers of Beis HaMikdosh. "Ki yi'po'lei mi'm'cho dovor la'mishpot bein dom l'dom u'vein din l'din, u'vein nega' lo'nega', divrei ree'vos bish'orecho…(Perek 17/Posuk 8). When there will [knowledge] that is beyond you for judgement [regarding] matters of blood, of law, of plagues, matters of dispute within your gates, you are to arise and go to the place that Hashem has chosen. The mussar interpretation expresses it as follows. When it is beyond you to understand the judgement [that Hashem has placed against you that your] blood [is spilled], the laws [and decrees that are enacted against you] the plagues [that befall you, it is because there are] matters of dispute within your gates. The fighting "within your gates" plants the seeds for so much destruction and pain. It is easy to look outward to blame the enemy and curse his evil doing. Of course the enemy who afflicts you is wicked, but you bear responsibility vis a vis Hashem for ultimately it is His punishment that is placed upon you. Thus, an antidote to such suffering is to repair the fighting and bickering that is within your own domain, over which you have control. That introduction does not require much elaboration. We are all aware of the fighting that exists and the pain it causes. Since that is so, it may seem that the entire system of Torah that we have leads to such disputes. Since our courts have a mandated multiple numbers of judges it is most probable there will be differing opinions as to the correct verdict. True, there is a required uneven number of judges ("Beis Din noteh") that will allow a decision to be reached, nevertheless the minority opinion is still certain of the correctness of his determination. The Mishnayos of the third, fourth and fifth P'rokim of Masseches Sanhedrin tell us that the majority is decisive and in the same breath remind the judges of the prohibition of L'shon Hara', not to tell the losing litigant (even in truth), "What can I do? I decided in your favor, but I was outnumbered." Thus, the field is ripe for contention and controversy. If that is so repulsive to Torah, what is to be done about it? The answer lies in how the people, and the judges in their special role, view the system to which they owe their allegiance. The Posuk cited above, in its context of Pshat, tells us that it is expected that not every difference of opinion will be resolved. The Torah knows that there will be significant differing conclusions that different people will reach. The Torah also knows that those bearing serious convictions will not be easily deterred from their decisions. Thus, the system that the Torah decides provides a mechanism for adjudicating those disputes. Ultimately the Sanhedrin Ha'G'dola will be obligated to render a verdict that will be binding. Until the time such a verdict is rendered, the judge is allowed to maintain the correctness of the conclusion that he reached. He may say to all that his discernment is true, not theirs. Yes, he is limited in the context in which he expresses himself so as not to violate the prohibition against gossip and slander, nevertheless, in the proper forum he may argue against the majority opinion which decided the case or question that was brought before the court. Not only is he allowed to persist in his beliefs, he may continue to decide the Halacha in the way he sees things. This freedom of decision, however, is not without a conclusion. Once the Sanhedrin renders its decisions, its rule is binding and demands complete allegiance and forbids competing verdicts. In fact, the Zokein Mamrei, the rebellious "elder", is liable the death penalty if he continues to issue halachic decisions contrary to the ruling of the Sanhedrin (Posuk 12). The Torah expresses the faithfulness to the findings of the Sanhedrin by writing, "… lo sosur min ha'dovor asher ya'gi'du l'cho yomin u'smol" (Posuk 11). Do not turn from the word they [the Sanhedrin] will tell you, neither right nor left. As Chazal express it (as brought in Rashi), even if they tell you right is left and left is right, you are obligated to follow their ruling. Ramban explains that "v'yo'du'a hu she'lo yish'ta'vu ha'dei'os b'chol ha'd'vorim na'nolodim". It is known that minds will not agree about all matters that will come about. "V'hi'nei yir'bu hamachlokes v'tei'o'seh ha'Torah ka'moh toros". There will be an increase in disputes and the [one] Torah will become many torahs. Thus, Ramban continues, the Torah decided the law that we must adhere to the ruling of the Beis Din HaGodol in all that they explain the Torah. Therefore, it seems we have a system that will seemingly put an end to the differing opinions of the judges. We may still wonder, is the system effective. How can I believe differently by fiat? I have come to a conclusion and, in my mind, that conclusion has not been disproved. To approach solving that question, we may ponder the additional outcome the Torah sees from the Zokein Mamrei. After telling us of the aforementioned death penalty the Torah writes, "V'chol ho'om yishm'u v'yi'ro'u v'lo y'zi'dun 'od" (Posuk 13). [Execute the death penalty at a time when] all the people will hear and be frightened and will not act maliciously any longer. We may ask, this warning should be for the judges only. Only they are involved in the disputes of the courts and only the most outstanding of them could reach the level of Zokein Mamrei and presume to differ with the decisions of the Sanhedrin. hear and fear? If so, why is it necessary for the people to The answer is that thought the focus of these mitzvos are the courts, they deal with feelings that could be possessed by the entire populace. The people might be only to happy to be on the side of the minority which challenges the authority of the ruling bodies. It is easy to criticize and to say they do know nothing about which they are talking. Thus, the warning is to all. The judges must be particularly alert, but the people must have awareness as well. The Torah has empowered to the judges to decide. The same Torah that gives us the other 612 Mitzvos presents us with this as well. Accept the Sanhedrin's rulings. You think you know more than them? Perhaps you do. Nevertheless, they are right not you. They are right since the Torah invested its authority within them. The Rambam writes (Hilchos Y'sodei HaTorah Perek 7/Halacha 7) concerning the obligation to accept the words of the Prophet: "V'eph'shar she'ya'aseh os o mofes v'eino novi." Perhaps an individual will perform a sign that qualifies him as a prophet when he is, in fact, not a prophet? Rambam explains that it is the same in court when we accept two witnesses to decide a case. Perhaps the witnesses are lying and they have not been discovered? The answer is that the Torah commands us to follow the laws of the courts. "V'af 'al pi kein", nevertheless, it is a Mitzvah to listen to the Navi and a mitzvah to follow the courts rulings. It really does not make sense to argue with the Sanhedrin since the G-d who gave us the Mitzvos, gave us this as well. In fact, if the lesson of the Sanhedrin would be learned well, it would not relieve disputes, it would prevent differences of opinions from becoming disputes. If the lesson of the Sanhedrin would be learned well, we would inherently be aware of the difference between a machlokes l'sheim shomayim and one that is not. If the lesson of the Sanhedrin would be learned well we know to embrace the former and flee the latter. The month of Elul prepares us for Yom HaDin, Hashem's Day of Judgement. If we learn to handle the "din" in our world we have a right to turn to Him on Rosh HaShanna and entreat Him to spare us from harsh judgements. We err and we have mistakes, but our loyalty is unquestioned. We accept the words of his sages and know that sometimes we are unaware of the difference between right and left and thank Him for providing us with the teachers who will lead us to do His will. Shabbat Shalom, Chodesh Tov K'siva Va'chasima Tova Rabbi Pollock