Cover sheet Linnet Kestrel mka Barbara Gordon "PENNETYLE

advertisement

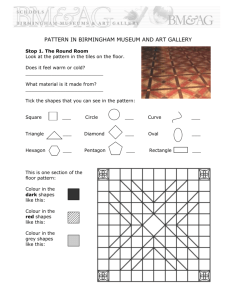

Cover sheet Linnet Kestrel mka Barbara Gordon "PENNETYLE": DECORATED FLOOR TILES Description: This is a set of decorated tiles, with the stamps used to mark them. Tile floors were popular in England from the 1200s to the Reformation. A variety of decorations were used, some of which are demonstrated in this panel. These tiles would have been made in East Anglia in the mid-fourteenth century, for the house of a minor noble or wealthy cleric. The stamps may have been made to the design of a more important client, but the tilery retained and used the stamps (Eames 1985 p.10). "Decorated tiles provided a vivid patterned pavement for the floors of royal palaces, ecclesiastical and monastic buildings, and prosperous merchants' houses in the Middle Ages. ... Decorated tiles, especially two-colour tiles, were essentially part of Gothic architectural decoration." (Eames 1985 p.4) Sources: The stamps are based on the tile stamp found at the North Walk Pottery site, Barnstaple, Devon. The inlaid design is based on a quadrant tile pattern found in Winchester and Oxford. I also studied a 15th c. German tile fragment in my possession. Summary: Carved relief and counter-relief stamps from alder, rolled terracotta clay on sand table, formed, stamped, keyed, trimmed, inlaid white clay in counter-relief, scraped down, let dry, glazed with commercial lead glaze, some with copper filings added for darker colour, once-fired. Ill.1: Barnstaple stamp and tiles Ill.2: tile backs showing keys Ill.3: inlaid quadrant tiles Ill.4: tile pavement with inlaid and single colour tiles All decorated tiles were known as peynt tile or pennetyle, "peynt" meaning simply "decorated" (Wight p.55). Various methods of combinations of tiles were used, sometimes in complex schemes. Floors were laid with plain or relief tiles in alternating glaze colours, with tiles inscribed or stamped with line patterns to imitate mosaic, and with tiles inlaid with designs in contrasting coloured clay. Earlier floors were laid with elaborate mosaics of tile, and expensive schemes of tiles illustrated by sgraffito were prepared for royal residences. Construction: The tile STAMPS are carved from alder wood. Only one tile stamp has survived from the English industry - a wooden relief stamp from the Barnstaple works. The stamp appears to date from the 1600s, but the surviving Barnstaple tiles show a strong continuity with medieval examples, so it is probable that similar stamps were used throughout the period. Some surviving inlaid and incised tiles also show grain marks and cracks characteristic of wooden stamps, though there is some evidence that lead stamps were used for incised decoration (Eames 1985 p.33). The stamps produce relief and counter-relief tiles. The counter-relief was intended to be filled with white inlay, but in period the inlay was occasionally left out, either intentionally or not. The counter-relief tile is a quadrant or four-tile design of a Catherine wheel or rose window. It is based on two patterns, one from Winchester, and another, somewhat debased, from Oxford. The relief tile is a fleur-de-lis, emblem of the Virgin Mary, and thus wildly popular throughout period. The CLAY is red earthenware for the body of the tiles, and white pipeclay for the inlay. I added grog and sand, both to reduce shrinkage, and to approximate the poor quality of clay in the 15th c. tile fragment I have. The tiles were FORMED in a frame and put aside to dry somewhat. The Barnstaple stamp was used on leather-hard tiles (Eames 1985 p.29), but I experimented with different degrees of dryness. Like surviving period tiles, the tiles are quite thick, roughly 20-25 cm (Eames 1985 p.10). There was thus very little problem with warping while drying. Some of the tiles I left as PLAIN QUARRIES, to be glazed with lead and leadcopper glaze only. Several of these I scored, so that they could be broken after firing into triangle shapes to fill in the edges (Eames 1985 p.18) of the panel design. I returned the other tiles to the form and stamped them with DECORATION by hitting the stamp up to 6 times with a wooden mallet. The Barnstaple stamp was apparently only struck once for each tile, but it is likely that the tiler was stronger and more practised than I was. I scooped between 1 and 4 keys out of the underside of each tile, an English practice which reduced the weight and drying time of the tile and helped it bond with the mortar (Emden p.3). The relief tiles were finished at that point. The tiles dried for a day, then the INLAID tiles had a layer of white clay pressed firmly on top. Again, I experimented with the white clay, running from firm plastic clay to nearly slip, on tiles of varying degrees of dryness. It was necessary for the tile to have hardened enough that the pressure of the white clay didn't distort the design, but if it was bone-dry the white clay cracked and peeled off. If the white clay was too liquid, it did not fill up the inlay, but covered the whole tile thinly. Once the layer of white clay had dried somewhat, I scraped it down with a knife until the pattern was revealed. I painted two of the relief tiles with white slip, an uncommon technique (Wight p.45), but rather attractive. I used a commercially prepared clear lead GLAZE for the inlaid tiles, adding copper filings to achieve the green glaze (Eames 1968 p.2). It is possible that tiles were glazed while damp by pouncing with powdered galena lead in a muslin bag (Wight p.45, Green p.62), but I chose health over authenticity here. The copper green came out rather uneven, so it may be that there were not enough copper filings (filing copper by hand is immensely tiresome), or that copper oxide was used rather than filings. Theophilus describes how to burn copper to ash for a pigment to use in glass-painting, which suggests that copper oxide was in use quite early. Further experimentation is called for. The tiles were glazed and ONCE-FIRED, which was the English practice (Eames 1968 p.3) rather than biscuit-fired and glazed, which seems to have been the practice for Flemish and Dutch tiles at the time. Bibliography: Cosentino, Peter Encyclopedia of Pottery Techniques Philadelphia, Running Press, 1990 Eames, Elizabeth English Medieval Tiles London, British Museum, 1985 Eames, Elizabeth Medieval Tiles: a handbook London, British Museum, 1968 Emden, A.B. Medieval Decorated Tiles in Dorset London, Phillimore, 1977 Grafton, Carol Belanger Old English Tile Designs: for artists and craftspeople New York, Dover, 1985 Green, David Experimenting with Pottery London, Faber, 1971 Loomis, Roger Sherman Illustrations of Medieval Romance on Tiles from Chertsey Abbey Urbana, University of Illinois, 1916 Ruscoe, William Manual for the Potter London, Tiranti, 1963 Theophilus On Divers Arts: the foremost medieval treatise on painting, glassmaking and metalwork translated by J.G. Hawthorne and Cyril S. Smith. New York, Dover, 1979 Wight, Jane A. Mediaeval Floor Tiles: their design and distribution in Britain London, Baker, 1975 Permission to distribute is given as long as credit to the author is retained.