CYBERACTIVISM AND ALTERNATIVE GLOBALIZATION

advertisement

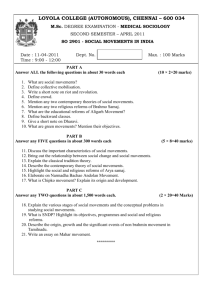

TYPOLOGY Networks of Dissent: A Typology of Social Movements in a Global Age Douglas Morris, Lauren Langman Department of Sociology Loyola University of Chicago 1 Introduction The rapid proliferation of information technology has led to major social changes in the economy, politics and culture. Various globalization processes have depended on technological innovations of communication and production, especially the microchip, computer, and electronic networks of financial and information flows, which are now often integrated in the activity of networks via the Internet. Castells (2001) notes that the Internet fits well the structural aspects of the network society emergent in late 20 th century. As the Internet is adopted in various social spheres, such are dialectically reconstructed according to network logics combined with historically formed and emergent values and ends. Economic enterprises are now formed through the net as complex production and distribution networks, rather than as hierarchical structures, which seek to link to nodes (nations, regions, locales) which maximize productivity, fluidly dropping those less productive nodes (often devastating such locations in the process, extracting capital with little obligation to locations under the current neoliberal economic standards) according to ever more refined, intricate methods of transnational computer network mediated coordination. The economic geography has been gradually transformed from an international system of powerful nation state-based corporations to a global system dominated by transnational firms and their regulatory agencies, various IGOs and NGOs. Networks of states (E.U.) and state interests (WTO, G8, etc.) have now arisen to coordinate transnational political activities. Notwithstanding these changes, capitalism remains a system of domination, exploitation, and despoliation of the environment with powerful nations acting as both agents of transnational capital and in a continued legacy of imperialism. Culturally, the Internet has facilitated the spread of hegemonic ideologies of neoliberalism, instrumental individualism, and consumer culture. However, the Internet needs to be understood dialectically. On the one hand, the Internet is a means through which capitalism sustains it profits, globally coordinates its activities, and maintains its hegemony. On the other hand, in resistance to the oppressive aspects of contemporary society, new social movements are using the net as a tool and/or a social space to engage various social spheres. The Internet is now used as a medium for resistance via “cyberactivism,” those forms of political actions, mobilizations and pressure, and views and strategies that would foster social change (Langman et al 2002). Social movements are now developing as global networks of dissent, such as the alternative globalization movements (AGMs) which first came to widespread notice in the North with the alternative globalization mobilizations such as in Seattle, Prague, Genoa, etc. Following Poster (2001), the Internet can be thought of as both a tool and as a community or social space. That is people, organizations and networks work through the Internet as a tool for communication and in the Internet as an electronically mediated social space. Using Weber’s classical categories of politics, economy, and culture, for the purposes of distinguishing the variety of types of contemporary cyberactivism and for organizing future research, we suggest a straightforward typology of six types of cyberactivism and social movement networks which have developed through the Internet. In summary, Cyberactivism through the Net is seen in: 1) Internetworking, 2) Capital and information flows, and 3) Alternative media and theory, specifically: A. Alternative media and B. Alternative theory networks. Cyberactivism in the Net can be seen in 4) Direct cyberactivism (hacktivism), 5) Contesting and constructing the Internet, and 6) Online alternative community formation. We illustrate these types of Internet mediated action and interaction based on observations of alternative globalization movements and other movements. Resistance and Transformation in the Information Age As Sassen (1998) and Castells (1996) have demonstrated an essential moment of globalization consists of vast flows of electronic information, capital (legal and illegal), and movements of human populations. To understand social movements today we must also consider global flows of culture, international military/police actions, environmental toxins, and informationally mediated social movements and cyberactivisms. The coordination of a global firm typically involves thousands to hundreds of thousands of daily computer-mediated transactions across hundreds of offices, plants, and/or research centers throughout the globe. Financial transactions from ATM deposits/withdrawals to stock trades flow through electronically integrated global networks. These networks have enabled the internationalization of currency markets in which currency speculations, investments, and payments have become ever less dependent on geographic proximate and location. So too have electronically mediated information flows transformed politics and culture, usually in terms dominated by European politics and culture. There are also massive flows of people moving across the globe, from the TNC elites in their private jet to the millions of poor seeking better jobs in cities, especially those in the developed world. Certain industries such as elite 2 hotels, restaurants, and airport lounges cater to the elites. Likewise, certain smugglers and exploitative employers encourage the migrations of the poor. Also among the global flows are increasing amounts of toxins and the destabilizing results of industrial production. The Internet is a foundational moment of contemporary globalization. The Internet has made once private information available to a greater number of people. Actions of private corporations and governments are now more transparent, accessible to larger numbers of people—much of which those in power might not wish public. In many authoritarian States where governments control information and the media, a variety of “alternative” web sites are popping up—as has been happening recently in the Middle East. Insofar as the global economy depends on vast networks, these same networks have the potential of offering new forms of communication, resistance, and progressive mobilization—as has been well noted by Castells (1997) and Dyer-Witheford (1999). The growth and maintenance of the Internet has fostered an intertwining of local and global systems, a “glocalization” that has become a central theme for our age (Robertson 1992). The global impacts the local (and individual) and the local structures the nature of the global. While the globalized economy has become de-territorialized, it is nevertheless territorially instantiated. Otherwise said, global systems are grounded in local spaces and nodes of control that are concentrated in the administrative and service facilities found in the global cities (Sassen 1998). While the TNCs marshal global resources, and global institutions increasingly manipulate/control nation-states, the control functions that appear in the local nodes can be sites of protest. In the AGMs, social actions are organized around local protests at global conference sites and/or command and control centers. Yet, these local actions are organized and publicized through international networking facilitated by the Internet. Domination seeks to maintain itself, but it continually fosters challenges and resistance. To sustain their hegemony, in historic blocs terms, the transnational capitalist class attempts the ideological control of cultural understandings to secure the “willing assent of the masses” to ruling class interests. But, hegemony is an ongoing process that continually faces contestations. Capitalism created the proletariat, and while the workers did not overthrow capital, labor did achieve many reforms and benefits. Such reforms coupled with nationalism and consumerism, however, have sustained its hegemony. The resistance to neo-liberal economic globalization is a historical juncture not unlike the early decades of the twentieth century, when labor challenged the power of industrial capital and/or the bourgeoisie state. We are now at a historical juncture in which global capitalism, networks of rarely democratic states, and various oppressive cultural hegemonies may be challenged but either sustained by reformist strategies or democratically transformed by as and Hardt and Negri (2000) note the varied multitudes, whom are organized in a great variety social movements being organized increasingly globally and increasingly as networks of networks integrating local, regional, and global issues through the Internet. Cyberactivism and Social Movements: Toward a New Politics The nature of social mobilization is changing before our eyes. “Cyberactivism,” the extensive use of the Internet to provide counter-hegemonic information and inspire social mobilizations, is a new phenomenon in which a variety of new forms of movements and protests are using the most modern information technologies. Some organizations and efforts have been local, such as the Zapatistas. Some movements have focused on specific issues, such as in the Landmine Treaty or dolphin safe tuna fishing. Some of the net-mediated alternative globalization mobilizations have had a major impact, such as the widely publicized moblizations in Seattle, Washington DC, Prague, Porto Alegre, Quebec City, Genoa, etc. The emergence of such movements requires us to take a descriptive survey to understand how the Internet is used that may help elucidate the causes of such movements and what shall the fate of such movements be. Hence, we focus here on the actual use of the Internet. It is necessary to note a plurality of types of sites from local to global extent of cultural, political, economic, environmental, and social justice based democratic action. To organize a democratic information society, DyerWitheford (1999:193) distinguishes four distinct moments, “a guaranteed annual income, the creation of universal communication networks, the use of these in decentralized participatory counterplanning, and the democratic control of decisions about technoscientific development.” While struggles in each of these areas might in Dyer-Witheford's terms establish its own “beachhead,” the Internet allows these beachheads to share some intelligence and personnel and, on many occasions, join together as a progressive force contesting neo-liberal globalization. Social movements and projects in civil society are working in all of these spheres and more. We would like to suggest that there are six main types of “cyberactivism." These are a combination of two factors: first, type of social action in regards to the net either “through the net” (the net as a tool) or “in the net” (the net as a social space or site of contestation); and second, type of social sphere (economic, political-relational, and 3 cultural). Hence, cyberactivism through the Net is seen in: 1) Internetworking, 2) Capital and information flows, and 3) Alternative media and theory: A. Alternative media and B. Alternative theory networks. Cyberactivism in the Net is seen in: 4) Direct cyberactivism (hacktivism), 5) Contesting and constructing the Internet, and 6) Online alternative community formation. We define the types of cyberactivism preliminarily as follows. Regarding this typology, please note: While the following ideal typical categories are distinguished for analytical purposes, many of these phenomena develop in tandem, in synergy and/or dialectically. Also note: While we focus on AGMs here, a caveat is that many actions, movements and communities on the Net are reactionary, directly reproducing various types of oppression or ascetic withdrawal or ludic in carnivalistic abondon, ritualized primal furor, or pop alternative cultural consumption, not challenging structures of power. Also note that a common form of sub-categorization is to note a macro mainstream social type, grass roots and/or new type, and micro type of net structuration (agenic structural formation). Social Movements Through the Net 1) Internetworking: The Internet has enabled the wide spread expansion of established movements. We would like to disinguish three types of internetworking: a) organization and network coordination, b) grass roots global internetworking, and c) direct action coordination. Regarding a) institutional coordination: Just as many mainstream corporations and media now have an Internet presence and increasingly conduct their affairs on the net, traditional social movement organizations such as ACLU, NAACP, and AFL-CIO and new social movements such as NOW, ACT-UP, and GreenPeace maintain online resources and organize online in diverse ways. 1 The Internet is now used as an effective medium to extend the reach of existing struggles and enable new actions. A number of more established environmental groups, feminists, human rights, and other movement groups have had web sites for years. Many organize through listservs and provide websites with alternative information/articles, news/plans of demonstrations and ways that people can get more information, more involved etc. social movements have expanded on a global scale. An example of this is the political lobbying of The International Campaign to Ban Landmines (ICBL), which involved extensive NGO and social movement networking through the Internet. This resulted in the Land Mine Treaty of 1997 and Nobel Peace prize for the campaign's efforts. Through global networking, ICBL continues to generate online reports through “collecting and analysing data relating to antipersonnel mines… to evaluate the overall progress of the international community in eradicating this insidious weapon”. 2 Another instance of linking across movements is the use of email and web-based media in conjunction with local protests to inform the activities of United Students Against Sweatshops (USAS) movement. USAS formed in 1998 to protest the use by Universities of overseas apparel sweatshops to produce University paraphernalia (a multi-billion dollar industry). Partly through consultation with various progressive labor and human rights organizations and through networking internationally with indigenous rights and labor organizations, USAS groups are well informed in terms of labor issues and theory and link their online discussion and websites to broader issues such as the WTO and demands for living wages for all workers. At the same time, the USAS affiliated groups are focused in their strategies and demands, having a multiple point program of demands for University disinvestments and monitoring of that. The linking of USAS via Internet media to other enduring activist organizations has resulted in socialization of student activists into sophisticated activist theory and practice. Through internet use, we may be seeing a qualitative shift in the sophistication of student activists that will influence their success in subsequent activism, enabling the creative efficacy of movements and the civil society. Regarding b) grass roots global internetworking: Various AGMs as alternative globalization movement protests are expressions of a form of political networking and internetworking, often across a wide variety networks/movements cooperating with others at odds, that culminate in mobilizations and diverse sets of actions by a diversity of groups. A fundamental change in social movement activity is the linking of diverse movements into super movement spheres for the networking of information and resources and the creation of universal social justice and rights charters. The extensive movement networks which created universal rights statements such as the Hague Agenda for Peace, the Earth Charter, and Charter99 for Global Democracy, may become significant global actors by 1 See SocioSite Activism directory, www.pscw.uva.nl/sociosite/TOPICS/Activism.html, and New Social Movement Network, www.interweb-tech.com/nsmnet/resources/default.asp, for lists of movements on the web. 2 See Landmine Monitor webpages, www.icbl.org/lm, August 2000. 4 influencing global civic bodies. (Morris, 2000) The various memberships and universal charters overlap in networks that forward social justice initiatives in many social domains. Waterman (1998) has noted that old labor movement organizations are making links with new social movements such as feminist organizations. Other movements are doing the same. International environmental groups now participate in social justice and labor issues. Feminist organizations are involved in diverse spheres of activity. Peace movement strategies include social justice and environmental work. Such global internetworkings and the global charters are signs of the actualization of a global sphere of movement activity. Within this global cyberactivism, movements form dense nets of links with other movements to quickly organize and manifest actions with local and global impact. Such internetworking is an alternative between a take on institutionalization as the outcome of successful movements (Tarrow 1995) and on the fluid creation and dissolution of movements (Castells 2001) without a fixed cadre of organizers or structure whose primary outcomes and means of power are symbolic. Various networks in the GJM mobilization encompass the spectrum of these extremes in some respects across time. However, over the course of the AGM mobilizations, in the WSF, in the Indymedia Centers (discussed below), and actors, networks elements and ideas across the mobilizations. Regarding c) direct action coordination: Action “on the streets” has been coordinated directly via cell phone and via PDAs accessing websites for updates on the logistics of campaigns. Such tactics were used in Washington D.C. during A16 2000 mobilizations and in Indonesia during ___. (We save further discussion of this point for later draft.) 2) Capital and information flows: We would distinguish three main types of net based economic activity, the sue of: a) mainstream networked channels of capital distribution, solicitation, and management by social movements; b) computer mediated barter banks and local capital pools and credit unions and collective goods coordinated via the net, and c) decentralized P2P media distribution networks. On a) networked channels of capital distribution: Large mainstream movement organizations and NGOs raise funds and coordinate capital through the Internet. Information resources are also extensive on the net including extensive information on foundations and grant making. Databases of movement organizations and contacts enable networking across organizations and coalition building. 3 Emails campaigns are not only used to organize protests (see direct cyberaction below), they can be used to solicit ongoing donations from members. Employees of established SMOs and unions and ESOP corporations, some of whom act as organizers in more radical social movements, can check their retirement accounts and investiments online. Larger activist organizations use wire transfers coordinate by email. These adaptations to the modes of managing capital by the public and social movement sector to the Internet as a confluence and site of contestation and accommodation to capital (sometimes in the life of same person or activity of same organization). While new AGMs networks, which are extremely diverse and usually transitory, tend not to use of bureaucratic organization methods, new groups within and across various AGM networks do use net-based capital flows. For example, Indyemdia now solicits and accepts donations over the net via PayPal. These issues are relevant in advanced industrial societies where roughly 30 to 60% of the population is now online as of 2002 data. 4 However, it should be noted that in many developing/underdeveloped nations that less than 1% of the population has online access, let alone knowledge and resources to use. (But, this anticipates the digital divide discussion under section 4. below.) On b) computer mediated local capital pools: As co-op sectors and alternative community organizing projects organize, forms of decentralized forms capital sharing and accounting may expand. (We save comments on this topic for another paper or draft.) On c) decentralized P2P media distribution networks: This might be seen as a form of alternative media but it is actually a major site for contesting information age capitalism (qua information capital as private property) and forming alternative information distribution networks. The propriety of digital information continues to be challenged by post-Napster peer-2-peer, p2p, distribution networks based on free/liberated software such as Gnuttela, KaZaA, and WinMX.5 Indeed, the attack on Napster may have been counter productive to the goal of 3 For instance, see the extensive database at the Hague Appeal for Peace website, www.haguepeace.org See NUA Internet Surveys: http://www.nua.net/surveys/how_many_online/index.html 5 For information on p2p networks, software and issues, See: http://www.zeropaid.com/, http://www.infoanarchy.org/. Gnutella’s distributed file-serving software was an early alternative to Napster, 4 5 Media conglomerates to suppress digital piracy and counter culture competition in that the architecture of pirated and alternative noncommercial media distribution is now decentralized, hence much more difficult to control. Decentralized networks dedicated to sharing digital media are probably here to stay, as long as the net is a relatively open system. It should be noted that cultural media can be the carriers for encrypted political messages and were used as such as the use of messages in electronically transferred pornography by the Al Qaeda network. Various alternative media and distribution processes are of course used by a whole range of – from fascist to conservative to progressive to radical – politicized artists and musicians, can serve simultaneously as political organizing venues (political bands and protests/cyberactivism go together), online media distribution, and alternative media. 3.A.) Alternative media and theory: Alternative media: We note three types of alternative media on the net: a) alternative media, b) grass roots global media and information networks and c) counter-surveillance measures. On a) alternative media (including variously, online alternatives to mainstream media, social movement media, and local media online): Just as major newspapers now cultivate online readerships, established left/right media are using the net to distribute part or all of their publications stock of articles and recruit readers. Consider: Encyclopedia Brittanica has moved online. Specialized professional publications are moving online. Many persons online now use the net as primary source of news. To challenge the purile, infotainment of corporate news that increasingly conservative (six TNCs control the bulk of global media (G___ 199X)), online alternative media and knowledge bases have become a major source of cultural information and formation of activism and movement internetworking. Various online media services such as Common Dreams and AlterNet are developing substantial readerships.6 Alternative media on the net have diversified greatly. MediaChannel.org, which networks around media topics, including online issues, lists roughly 1000 media affiliates, many with left/alternative focus. Just as corporate and alternative media have moved online, so do many social movement organizations (right, center, left— new/old—local/regional/global) use net media to recruit, inform and engage members. Alternative media formats online are diverse, ranging from online zines and blogs (individualized web logs) to alternative news wires. Many community networks, sometimes called freenets, have developed on the net through combining alternative local political discourse, civic interfaces, and business portals (Castells 2001). Some successful projects include local media resources and possibly interactive communication with civic institutions and transparency of local government. Large networks of such community networks have begun organizing globally in the last few years. 7 Networks such as Association For Community Networking seek to preserve and expand the development of new virtual public spheres through mutual support, shared strategies and local-global or glocal networking. On b) grass roots media networks: Grassroots networks are hybrid constructions. They include often networking and the fluid circulation of efforts by independent individuals, professionals from mainstream media organization groups, movement groups, and networks of networks. Email and usenet newsgroups are among the earliest forms of net media used as grass roots news media. For cyberactivism: Listserves and newsgroups are both primary organizing tools and sources of news and analysis (and yes, for community formation). Through increased interconnectivity of information technologies, information, and communications now flow quickly to a wide geographical audience, often as a chain of events is still occurring. Various forms of information media – websites, movement listserves, bulletin boards, even chat rooms for develping stories – are used to develop and expand coverage of media often difficult to obtain through corporate sources, or delayed through alternative editorial process. To date, grass roots online sources of information are highly decentralized and little subject to corporate or governmental control or censorship. The Independent Media Center network (or Indymedia) and related alternative media have formed as cultural resistance and democratic communicative practice on a global platform, covering many local, national, regional, and global issues—realizing the potential of the internet as a new virtual public allowing users to share files across a decentralized network using shared indexes without reference to a central website. See Gnutella World website: www.gnutellaworld.net or Gnutella website: gnutella.wego.com. 6 Common Dreams NewsCenter, www.commondreams.org, lists (in left column) alternative media sources (and corporate media sources online). Other popular sites include AlterNet www.alternet.org, a project of the Independent Media Institute, WebActive www.webactive.com, and BuzzFlash Report www.buzzflash.com. 7 An early conference was the First European Community Networks Confrence in 1997, http://www.bcnet.upc.es/ecn97/. More recently a second world conference was held: II Global Congress of Citizen Networks, http://www.globalcn2001.org/. 6 sphere. 8 Around political events and coalition projects, the net enables alternative press projects with small budgets and staff to link together to form fluid networks of sophisticated media services, a key feature of which is interactivity. Often, to pool resources, a dozen and more media groups collaborate (by necessity via the net) to produce and distribute large projects such as video documentaries of large AGM mobilizations. Such networking also occurs now at the level of alternative media policy and strategizing. 9 Alternative media in fluidity of form and especially the progressive left with decentralized processes are paradigmatic cases of the evolution of Information society into networks of crisscrossing networks contesting over hegemonic codes/discourses. Indymedia is a case in point: the Internet enables this network of media collectives, organized often enough as local networks (or collaborating often as such), to operate in a decentralized manner while serving as an independent and free press network with common net portals and at the same time serving as a network of and for media activists and local media collectives/networks to cover directly news on the streets and to give voice to marginalized issues/passions. The Indyemdia network developed through providing grass roots coverage via the Net of the alternative globalization movement protests, starting with the Seattle anti-WTO mobilization on through D.C., Prague, Genoa, etc. Indymedia is a cybermovement (that has developed in parallel and synergy to the AGM protests), which while grounded in the efforts of local collectives, also covers global struggles against social inequality and oppression and for social justice. Content and policy wise, the IMC network is a free press publishing network, conceiving itself both as a comprehensive alternative, activist, grassroots media service. Culturewise, like many radical online projects, Indymedia is based in part on the net hacker culture (in it’s positive sense) of the sharing of free/liberated software (see section 5. below) and on the collective production of media at local levels in fluid usually consensus-based affinity group/working groups. A central principle for Indymedia is to be an open resource of information on many issues and to run its editorial policy and management of activities in a grass roots participatory manner. The mission of Indymedia is contested with some advocating more of a free press/speech approach and others seeing Indymedia as a network of media activists. While many Indymedia locals initially formed to cover AGM mobilizations, the network is now offering media support for many types of social movements at local and global levels. There is an organizing intention to stay decentralized or at the roots so this may not be a transitory movement media but a long term diverse decentralized left movement, providing organizing challenges are overcome, chief amongst which are overcoming network wide decision making issues across locals speaking many languages and with individuals and groups espousing wide array of ideologies. On c) counter-surveillance measures: Another aspect of alternative net media, more on the research and strategic organizing end, is making privileged communications and information increasingly transparent. This open character of information on the net (which rightly concerns privacy advocates relating to personal information) is the basis for an intriguing and powerful type of cyber-activism is the counter-surveillance measures that labor and interested groups have taken to object to corporate activities. Because localized labor struggles have lost some of their effectiveness in the globalization of production and supply chains, labor struggles are using the Internet to target the softer-side of the capital circulation process, or the market. For example, in San Francisco in 1994 an alliance of city union workers at two newspapers battled for better wages and working conditions by not only organizing a labor strike and boycotting the newspapers but also circulating a list of "scab advertisers." At a more grassroots level, the personal use of electronic media such as camcorders have ushered in a new era of countersurveillance by citizens of activities ranging from police brutality, as in the Rodney King case. 10 In various social conflicts, through access to corporate and government electronic documents, databases, etc., activists are developing new strategies to mobilize and to challenge capital and government, forcing more socially accountability. 3.B.) Alternative theory networks: Theory and strategizing is another level of the culture of resistance conducting online. While theory is mostly engaged offline, as in the big AGM mobilizations at counter-summits, strategizing 8 Note that some new progressive alternative media adopt the same approach to freedom of news that the free software net does to code: open access and free use. For examples of various alternative media, see the Independent Media Center (IMC) or Indymedia www.indymedia.org, www.infoshop.org, and Direct Action Media Network damn.tao.ca websites. 9 For instance, see these conferences: Underground Publishing Conference, http://www.clamormagazine.org/upc/, and Reclaim the Media!, http://www.reclaimthemedia.org/. 10 See Witness website, www.witness.org, for example of alternative media source using alternative sources of video. 7 which creates new practices/theory in larger networks is often/usually conducted via the Internet. Today, alternative/left/radical think tanks/networks and educational networks are going online, albeit at a slower pace and regretfully with less material than such as online mainstream projects such as the University of Pheonix and the Rand corporation’s database of publications. The World Social Forum, WSF, a major global organizing theory and strategy forum, emergent from AMG mobilizations—that some have announced as a new International for the oppressed, has been organized somewhat online and presented online documentation, with some online interfacing, including during the 1st social form in January 2001 a webcast of a debate between selected WSF participants in Porto Alegre and World Economic Forum participants in Davos. Of long term import will be the ability of the WSF as a forum for a great diversity of interests in globalization from below. This can only be accomplished through a combination of extensive long term physical and internet networking of meta-networking of networks.11 (More on this section in future draft.) Social Movements in the Net: The Net as a primary virtual space of social action and interaction is a very new phenomena. We interpret the Net as complex space in which many types of social relations are engaged and which develops as a space of diverse symbolic, linguistic, and media structures/practices through community use and formation. An important dialectic should be noted: Social research has show that interactions via the Net are generally not isolated from person-toperson intereactions in the spatially localized offline world and generally enhance such (Castells 2001). However, online interactions are not necessarily dependent on offline interactions. 4) Direct cyberactivism: Another type of cyberactivism is the use of the Internet as a primary grounds for political action. We would suggest three subtypes: a) virtual sit-ins, b) hacktivism, and c) cyberterrorism, destructive efforts against the net. On a) virtual sit-ins: Movements are utilizing e-technologies as a disruptive tool to industry and civil practices or temporarily dismantle the various stages of capital's circuit (e.g., the production and circulation of commodities). Cyberactivists disrupt net activity through electronic civil disobedience, for instance, in “virtual sitins” by mounting extensive traffic to shut down websites. It is possible to create disastrous results in the marketing and sale of commodities by disrupting corporate operations at public access points on the Internet. b) hacktivism: In new forms of resistance, which have been called "hacktivism", hackers appropriate or disrupt technologies for personal and political ends. 12 Wray (1998) mentions various examples. One example is a British hacker who cracked into hundreds of web sites worldwide and circulated anti-nuclear messages. Another instance of cyberactivism has been the Zapatista movement. This was the first “peasant” uprising to use various web sites and e-mails to draw international concern to the problems of indigenous peoples. The Zapatista movement as an instance of savvy cyberactivism, while grounded in profound local justice issues, linked these to a global analysis. Another example: The conflict in Kosovo was the first war to utilize the Internet. Denning (2000) writes, “Government and non-government actors used the Net to disseminate information, spread propaganda, demonize opponents, and solicit support for their positions. Hackers used it to voice their objections to both Yugoslav and NATO aggression by disrupting service on government computers and taking over their Web sites.” Hacktivists, perhaps working for their respective governments, have disrupted and infiltrated a number of Israeli and Palestinian websites, often putting pornography on the web pages. c) cyberterrorism: More forceful than such cyber-disruptions are the prospects of cyberterrorism. While computer viruses spread via the net have caused billions in economic losses (and the escalation of such antics, often by youths using straight forward software, is of concern), hacktivist attacks for overt political purposes have been sporadic and small scale to date. Yet, government investments in cyberdefense measures are increasing. To date, hacktivism is the province of individuals and underground cadres of actors. While direct cyberactivism at the level of net public access points is a viable and quasi-legal form of activism, how the use of illegal hacktivism by social movements may unfold is yet to be seen. It is conceivable that through an extensive viruses and cracking websites 11 See World Social Forum website, http://www.forumsocialmundial.org.br/, and media resources, http://www.forumsocialmundial.org.br/eng/temas.asp and http://iota.procergs.com.br/forumsm/home.asp. 12 For examples of hacking for personal reasons, see Lemos’ (1996) discussion of the Minitel, a government sponsored bulletin board that hacker's transformed into a system that included personal messaging, and Cleaver's (2000) discussion of the ARPANET, the predecessor of the Internet. 8 that corporate and state networks and even the Internet in general could be collapsed, with profoundly catastrophic results—consider that vital global transportation, health care, energy, and food distribution networks now depend increasingly on Internet mediations. A Net collapse of even several days would be disaterous. Targeted infiltration of intranets is perhaps more plausible. With the number of activists online continuing to increase, incidents of various types of direct cyberactivism can be expected to grow in number and scale. 5) Contesting and constructing the Internet: Types of contestation of the nature of Internet and its relation to inequality and democracy include: a) movements to democratically inform the structure, ownership, and technical aspects of Internet media and technology, b) activism to create wider access to the internet, crossing the digital divide, and c) planning and development of the social use of the net. On a) Structuring the Net: The nature of the net has been and is continually being worked out by think tanks, government agencies and legislation, civil institutions, industry, venture capitalists, net administrators, policy wonks, programmers, and in social movements. To understand the social fabric underlying the potential of cyberactivism, it is important to explore how Internet technology itself may be designed to facilitate or inhibit democratic interaction. One fundamental issue is the use of free (liberated) software, also more popularly known (and perhaps incorrectly) as open source software code. The open sharing of software was a key social practice in early programming cultures and is part of its continuing evolution. In the sharing of code, innovations spread across the net through a "gift" economy in which many functions were introduced that creators of the early computer networks did not envision. This evolved into a “hacker ethic” of sharing software. The free software movement 13 uses social practices of sharing code and seeks to formalize the hacker ethic with a copyleft or General Public License 14 legal strategy to make software a common resource, programming publicly available for modification. There are many types of free software applications, the makers of which hope to replace capitalist information economy with an electronic commons. For instance, the open source code in the Linux operating system now has significant share of various operating system markets, decentralizes control of computer systems architecture, democratizing such, and is a major competitor of Microsoft Windows. The open source Apache web server is increasingly used to mangage information services on the net. Lawrence Lessig (1999) argues that the ability of government to control the structure of the Internet is related to the nature of the code architecture of the net. Open code is less easy to regulate. The development and pursuit of electronic democracy in decision-making and public policy planning might depend in part on growing and maintaining a net based on robust open code and protocols. While the technical and legal criteria of software may seem distant from social movement activism, the free software movement is one place that activists may be proactive in guaranteeing some measure of public control over the development of the net. Social actors are addressing crucial matters of net development in legal debates over such topics as surveillance, taxation of Internet commerce, and copyright protection for media distribution. Institutionalizing a democratic architecture of the net is a base from which to empower other types of democratic planning necessary for any sustainable type of democratic society and openness on other leves of net services such as in alternative and local community based media and the ability to monitor governments and corporations. Related issues include the widespread use of private encryption technology as resistance to government and corporate surveillance (which is strongly resisted by so called democratic governments, especially post-9/11 with the introduction of Carnivore and government web log monitoring programming into many web servers). Advocacy efforts by various national governments (contest by groups such as the Center for Democracy and Technology and the Electronic Frontier Foundation15 aim to contest limits on openness on the net and advance democratic practices and constitutional liberties in the digital age. However, even if the architecture of the net is decentralized, there remain political economic problems of access. Regarding b) crossing the digital divide: In the information age, the terrain on which class battles are waged has dramatically shifted. It is not possible to protect blue-collar jobs and even white-collar jobs (and hence the basis of a market or any production based economy) in a global age with increasing use of robotics in production. Society must find the political vision and will to support deskilled workers and growing underclasses in finding avenues for training and retraining in the technologies of the information society. Closing the digital divide is a necessary part of See Free Software Foundation’s philosophy, historical, legal, and technical articles: http://www.gnu.org/philosophy/philosophy.html 14 See http://www.gnu.org/licenses/licenses.html 15 See http://www.cdt.org/ and http://www.eff.org/ 13 9 empowering the main victims of the information revolution and increasing their ability to form productive alliances with other sectors in contesting for broader political power. Overcoming disparities in standards of living are preconditions for any widespread use of the Internet for education and democratic political participation. It should be noted that many organizations working on Third World Development and eradication of poverty use various Internet media to network and promote their causes. Counter to efforts to expand access to the net are legislative efforts at increased taxes on net access and activity and hidden taxes in the form of high costs for access to broadband. Knowledge about how to use the internet is differentially available by class and a key determinate to alleviating the effect of the digitial divide in exacerbating various forms of inequality (Castells 2001). Regarding c) planning and development of the social use of the net: Organizations directly supporting social movements online and various types of cyberactivism and justice issues online have developed, such as the Institute for Global Communications (IGC) and NetAction. They foster various types of social activism and offer support services for use of the information systems by movements. IGC has played a key role in certain types of global organizing by providing organizing and communication services. In 1990, it co-founded the Association for Progressive Communications (APC), an international coalition of progressive computer networks. APC provides Internet services to nonprofits, NGOs and activists working in over 130 countries. IGC was a primary service provider at various UN world conferences, including “the 1992 United Nations Conference on the Environment and Development in Rio de Janeiro… and the 1995 World Conference on Women in Beijing.” 16 NetAction provides cyberactivist strategic resources. NetAction educates “the public, policy makers, and the media about technology policy issues” in these areas of focus: “the accessibility and affordability of information technology and the Internet;… use [of] the Internet as a tool for grassroots organizing, outreach, and advocacy;… effective grassroots citizen action campaigns and coalitions that link cyberspace activists with grassroots”. 17 NetAction’s website provides extensive helpful links for cyberactivists (including links to similar activist support organizations) and informative policy papers on the development of the Net. 6) Online alternative community formation: With the Internet, early online forums demonstrated the promise of a great diversity of “virtual communities” organized around common interests (Rhiengold 1993). A fundamental problematic is if Internet-based communities exist solely as “virtual” moments in cyberspace or do constellations of digital information have an enduring material basis for “reality.” Castells (2001) characterizes online interactions as less a space of communities (conceived as based on primary relations) and primarily extending already existing modes of relations or interests of individuals. We disagree. Wellman (2001), while agreeing with Castells on the increase in individualism in industrial societies, has extensively studied the nature of online communities and has argued that such communities, as networks of interpersonal ties are indeed “real” in terms of forming durable relations that provide an number of social rewards including sociability, identity and support networks. Social movement literatures have gradually (Klandermans 199x, Tarrow 1995) compiled a variety of incentives to engage in social movements, including individual rewards and skills building, solidaristic/social rewards, network pulls, and ideological framing. It stands to reason that online movements will find persons interested developing the community aspects of online relations. We note here three types of online community formation: a) Solidaristic association, b) new forms of mutuality, and c) individualistic networking. On a) Solidaristic association: This is the extension (online and into new movement networks) of pre-existing collective movement and social identities and strategies that value solidarity such as labor and more group focused identity movement formations such as civil rights and also more traditional religious and national identities online. Human beings have lived in groups and communities since the beginning of time. Most human communities till now have generally been based on physical proximity, common collective identities and shared goals and values. With the rise of the city, the growing division of labor and individualism, social ties became more attenuated—while people gradually, generally became freer and liberated from domination. With the rise of print and postal services social ties and relationships became mediated. People in urban settings formed smaller intimate communities of immediate family and neighbors and larger secondary networks of interaction in connections made in work, play, consumption, education, church, politics, etc. Print media allowed the emergence of “abstract communities” like Nation States sustained across great distances. In the 20 th century, electronic media, the telephone, film and 16 17 See Institute for Global Communications: History of IGC, www.igc.org/igc/gateway/about.html. See NetAction. Online: www.netaction.org/about. 10 television, expanded the range of available information and collective identities and movements expanded, but there was little interaction between the few and the many. With the proliferation of Internet use, there was rapid emergence of Net-based social relationships and communities, beginning with the scientific communities that shared information over the ARPANET, Telnet etc, the emergence of a hacker ethic of shared production there and early online communities like the WELL. Many such communities have been extended through community/freenet networks as metiond above in the discussion of alternative media. On b) new forms of mutuality: Online alternative community formation as an end in itself is a space for the transformation of society (such as in the still surviving and expanding in spaces from Usenet spheres and realms of MUD playing to new online religions and radical political forums. New online communities are the cutting edge of the net as mediator of collective subjectivity—the net as a space of play and ludic involvement which in alternative moments would transform hyper-tech consumerism of videogames into more humane forms of relating. The net is also a site of resistance to mainstream culture in many forms; anti-modern, future utopian, etc., which serve as a recruiting ground for activists and the play or critiques of modernity. Also, the net linking of diverse realms of dispersed nonlocal communities of common interest into networks of interest groups which may be emergently mobilized into larger public spheres. In terms of democratic potential, of great interest is the creation of collectivities based on shared values and projects, which resist in form and process the rationalized of life world and objectification of social relations. Such collective projects aim to create (ideally) intentionally local, cooperative and mutually supportive collectives. A case in point is the Indymedia network. Indymedia collectives that are both project structures and communities. In Indymedia, non-local collectives and relationships also form. Of course, consensus and collective processes do break down, becoming assimilated, at least partly, to cultural norms, by they ego-centric networking or traditional forms of collective identity drive action. However, whatever the failures, online nonlocal virtual communities have formed with some engagement of progressive utopian practices. It is interesting to note that just as in a) that net media projects, whether community based or nonlocal, are associated with community formations. To turn a standard McLuhanism: The medium is not only the message, it is the community—at least for those who make it or experience it so. On c) Individualistic networking: The pursuit of self-interests by individuals in many networks such as social movements. When used in an interactive manner, television and digital communications may be conceptualized, in theory and practice, as "autonomous media" (Dyer-Witheford 1999). That is, social actors use the Internet, and other technologies not only for the needs and intentions propagated by commercial marketing or social movement campaigns, but also to explore their interests. These above forms of community formation (and even in the same person with different parts of networsk) are not exclusive. Community formation online may be a mix of individualistic motives mixed with more traditional forms solidary interests (labor, feminism, environment, religion, even radical nationalism) and new forms of mutualism. Conclusions Since the very beginnings of recorded history, people have organized themselves to collectively achieve certain goals, communicate and share common interests. In face of what may be perceived of as adverse social conditions, they have sought to change those conditions. Today, given the nature of globalization as a form of capitalist domination in a networked society the long standing quest for a democratic society and egalitarian social relations, personal fulfillment, and now a clean environment has become intertwined with new technologies of production and communication. Neo-liberal globalization, a product of the intertwining of capitalism and these advanced technologies, has led to unique forms of resistance and social mobilization. Various social movements have globalized, networks of communities and local collectives online have formed, and AGMs have emerged as a responses to the injustices of globalization. Cyberactivism today is a diverse realm of activity. What is especially important to note is that while many of the issues addressed by cyberactive movements have a long history, these histories have been localized and the influences between them indirect. A critical issue for today is the extent to which the Internet and information technologies have become important aspects of coordination of networks of movements, communities, and activists across the globe. A key features of the recent AGM movements has been the extent of internetworking in which various diverse coalitions of human rights activists, feminists, environmentalists, and trade unionists join in concerted actions. Unlike many traditional social movements, these are not single-issue agendas, nor are the issues they address likely to wane in the distant future. Nor do these movement meta-networks engage the net. Rather, as 11 will be discussed in a future paper, we would argue that in complex networks the organizing modes, in and through the net, are not only not necessarily mutually exclusive, they are necessary to the survival of a viable counterhegemonic social sphere. Beyond types of sociability, activists and organizers who work together (as we observe is the case in AGMs as in previous movements) form over time online communities of undertanding where: sometimes close relationships are formed and new identities, ideologies are created and refined. Communities and ongoing relationships or interactions, whether online or off, become part of the social space where many of the above types of net mediated activity occur. To understand the potential and nature of these movements it is important to study how these networks of movements are informed by and informing of the same global networks and information technologies at the foundation of TNC. It is also necessary to understand distinctions and similarities between reactionary and progressive uses of the Net. Post 9/11, governments have been attacking civil rights and labeling AGM direction action protesters as terrorists. This invidious distinction serves only the interests of the most conservative power elites. Modern human society is the progressive exploration and gradual institutional formation in various social spheres of the democratic promises of the Enlightenment – liberty, equality, fraternity. The global reach and manyto-many linking power of information technology may assist humanity in realizing and recovering the importance of linking the local to the regional and global in social administration, providing varied sources of media, and enabling individuals to create and rectreate continually meaning, empowered lives. 12 EDIT: REFERENCES Boggs, Carl. 1999. The End of Politics. New York: Guilford Press. Brecher, Jeremy, Tim Costello, and Brendan Smith. 2000. Globalization From Below: The Power of Solidarity. Cambridge, MA: South End Press. Castells, Manuel. 1996. The Rise of the Network Society. Oxford: Blackwell Publishers. --------------------. 1997. The Power of Identity. Oxford: Blackwell Publishers. Collins, Patricia Hill. 1991. Black Feminist Thought: Knowledge, Consciousness, and the Politics of Empowerment. New York: Rutledge. Dyer-Witherford, Nick. 1999. Cyber-Marx: Cycles and Circuits of Struggle in High-Technology Capitalism. Chicago: University of Illinois Press. Giddens, Anthony. 1991. Modernity and Self-Identity: Self and Society in the Late Modern Age. Stanford: Stanford University Press. Habermas, Jurgen. 1975. Legitimation Crisis. Boston: Beacon Press. Hochschild, Arlie Russell. 1997. The Time Bind: When Work Becomes Home and Home Becomes Work. New York: Metropolitan Books. Langman, Lauren. l992. Neon Cages. In Lifestyles of Consumption, ed. Rob Shields. London: Routledge. LaClau, Ernesto, and Chantal Mouffe. 1984. Hegemony & Socialist Strategy: Towards a Radical Democratic Politics. London: Verso Books. Lichterman, Paul.1996. The Search for Political Community: American Activists Reinventing Commitment. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Melucci, Alberto. 1996. Challenging Codes: Collective Action in the Information Age. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Morris, Douglas. 2000. Globalization and the Interweaving of Movement Identities. Paper for Sociology Ph.D. program, Loyola University Chicago. Robertson, Roland. 1992. Globalization. London: Sage. Sassen, Saskia. 1998. Globalization and Its Discontents: Essays on the New Mobility of People and Money. New York: The New Press. Sklair, Leslie. 1995. Sociology of the Global System. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. ----------------. 2000. The Transnational Capitalist Class. Boston: Blackwell. Spretnak, Charlene, and Fritof Capra. 1986. Green Politics. Santa Fe, NM: Bear & Company. Tarrow, Sidney. 1995. Power in Movement: Social Movements and Contentious Politics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Teeple, Gary. 1995. Globalization and the Decline of Political Reform. Waterman, Peter, 1998. Globalisation, Social Movements and the New Internationalisms. London: Mansell. 13