The Progressive Age

advertisement

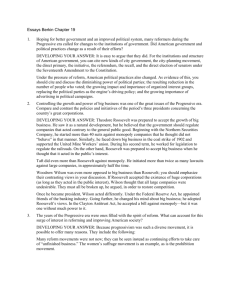

Introduction This chapter begins with the story of Jane Addams, who in 1889 founded a settlement house, Hull House, in Chicago. Addams was attempting to help immigrants and also give educated women like herself meaningful work. In the twenty years that followed, she and the others who ran it developed Hull House into a vital force within their community. It became a multipurpose center of activity: from restaurant to nursery, educational institution to labor museum. Addams's work in the community led her to seek assistance from city hall, and then from the state capital, and finally from Washington, D.C., where she became a strong advocate of woman suffrage and an expanded role for the federal government. Significantly, her path from personal action at the community level to political activism at the federal level personified a pattern that defined the Progressive Era of the early twentieth century—the 1890s to World War I. Against the backdrop of the tumultuous 1890s, progressive reformers shared common concerns about the power of wealthy individuals and corporations, especially the trusts, and the problems endemic to the new industrial age. Though their motivations varied, progressives united around a willingness to utilize an active federal government to curb the excesses of industrial capitalism and ameliorate the inequities it helped to produce. In doing so, progressives redefined American liberalism, which had long feared the potential tyranny of a powerful centralized government. Grassroots Progressivism, pp. 749-755 Progressivism was a grassroots movement that percolated upward into local, state, and national politics. The majority of progressives were middle-class urban professionals who wanted to solve the problems of American cities. Civilizing the City The cities became a focal point of the progressive movement. Progressives wanted them to become safer and healthier places to live. The attack came on several fronts. The settlement house movement, which began in England, put well-educated women in the role of social workers, tending to the various needs of the ethnically diverse big-city populations. Churches also attacked social problems of the cities through the "social gospel"—a mission to reform society as well as the individual. Christian clergy began to argue against the "gospel of wealth" in favor of Christianizing capitalism. Church leaders also spearheaded the social purity movement, which emphasized cleaning up the urban evil of prostitution. This drive often was accompanied by calls for the prohibition of alcohol, a campaign that demonstrated a strain of nativism as progressives stigmatized groups like the Irish, the Italians, and the Germans as heavy drinkers. All of these efforts were characteristic of the progressive movement, showing the progressives' belief that the government could solve problems without altering America's economy or institutions. Progressives and the Working Class Another hallmark of the progressive movement was to seek legislative solutions to social problems. An example of this philosophy came with the Women's Trade Union League (WTUL). The WTUL brought together middle-class and working-class women with the goal of organizing working women under the American Federation of Labor (AFL). However, the AFL rendered little support. Financial backing and leadership came from wealthy women who worked for higher wages and better conditions for WTUL members. A notable success came in the strike of New York City shirtwaist makers in 1909. But women's working conditions improved slowly, as the tragic Triangle Shirtwaist Company fire in 1911 dramatized. Increasingly, the bonds of the cross-class alliance were strained; the WTUL turned to the government for protective legislation. Such legislation was upheld in 1908 in Muller v. Oregon, which argued that women's special reproductive role justified shorter hours in the workplace. The National Consumers' League (NCL), another cross-class alliance, was formed in 1899 to encourage middle-class women to boycott stores and thus pressure companies into providing better wages and conditions for their female employees. Like the WTUL, the NCL—frustrated by the reluctance of the private sector to respond to the need for reform—turned to protective legislation in the early twentieth century. Progressivism: Theory and Practice, pp. 755-759 Progressive reformers developed a theoretical basis for their actions that borrowed from the ideas of reform Darwinism and pragmatism. In short, they believed that the universe was shaped by human action and that through intelligent and scientific approaches to problems the world could be made more efficient, productive, and just. Reform Darwinism, Pragmatism, and Social Engineering Reform Darwinism, pragmatism, and social engineering were key strands of progressive ideology. Reform Darwinism held that evolution could advance more rapidly through enlightened approaches to society's problems and that the federal government should play a key role in reform. Pragmatism emphasized the importance of observable consequences in determining the true worth of any idea and championed social experimentation. Informed by both philosophies, progressive reformers believed in social engineering—the importance of experts and scientific techniques in addressing the world's problems. Each of these views could be harnessed for the benefit of the many, but they also fostered a kind of elitism and could be harnessed, in the case of scientific management, to the detriment of industrial workers. . Progressive Government: City and State A millionaire by age forty, Thomas Lofton Johnson turned his back on business and entered politics in 1899. He was elected mayor of Cleveland, Ohio, on a pledge to reduce the streetcar fare to three cents, touching off a seven-year war between the mayor and the streetcar moguls. When Johnson responded by building his own streetcar line, his foes tore up the tracks and blocked him with court injunctions and legal delays. At the prompting of his opponents, the Ohio legislature sought to limit Johnson's mayoral power by revoking the charters of every city in the state, replacing home rule with central control from the capital, Columbus. In the end, Johnson had the city buy the streetcar system as well as the public utilities. Governor Robert La Follette of Wisconsin brought progressive reform to state government in 1901. With popular support and political savvy, he improved education, advocated railroad regulation, and instituted the first direct primary and state income tax in the country. Additionally, he initiated a cooperative relationship between state government and talented educators at the University of Wisconsin to draft more effective legislation. Wisconsin became the model for other progressive states, earning the title "laboratory of democracy." An emphasis on reform rather than party loyalty became a characteristic of progressivism. Democrats like Tom Johnson and Republicans like Robert La Follette could lay equal claim to the label "progressive." Hiram Johnson became governor of California in 1911, running on the promise to curtail the influence of the powerful Southern Pacific Railroad and give the state honest government. He introduced democratic reforms and signed an employer's liability law. Johnson also introduced the use of the initiative, referendum, and recall. His changes were the most beneficial to small business owners and entrepreneurs, who had new opportunities when the Southern Pacific was brought under state control. Progressivism Finds a President: Theodore Roosevelt, pp. 759-770 Theodore Roosevelt became president in 1901, after President William McKinley was shot and killed by an assassin. At the age of forty-two, Roosevelt was the youngest man ever to move into the White House. A member of the upper middle class and Harvard educated, Roosevelt had a wide range of political experience and would use his energy to strengthen the power of the federal government. The Square Deal Once he took office, Roosevelt quickly challenged the trusts and Wall Street in his suit against the Northern Securities Company, which was dissolved in 1904. Although he prosecuted trusts, he preferred regulation to antitrust suits, believing that there was a distinction between "good" and "bad" trusts. He outlawed railroad rebates through the Elkins Act and used the government as the mediator between the United Mine Workers and the anthracite mine owners in the strike of 1902 by forcing mine owners to negotiate with workers—all actions that marked a great change in the government's role in the years following the Civil War. Roosevelt claimed that he was only trying to give labor and capital a "square deal." His policies made him popular and easily reelectable in 1904. Roosevelt the Reformer Roosevelt was concerned with railroad regulation throughout his presidency. The Elkins Act, passed earlier, had not worked to end rebates, and Roosevelt wished it strengthened. In 1906, he supported the Hepburn Act, which eventually called for the Interstate Commerce Commission (ICC) to set railroad rates, subject to court review. Many progressives felt the legislation was a defeat for reform, whereas conservatives viewed the act with alarm. The final product was clearly a compromise between the two positions, and it represented a landmark in federal control over private industry. The year 1906 marked the high point of Roosevelt's presidency and effectiveness because he announced early after the 1904 election that he would not seek another term in 1908, a promise that made him a "lame duck" president. Yet he was aware of the public's continued interest in reform, which was being spurred by "muckraking" journalists who were exposing corporate and political wrongdoing. Muckraking efforts helped to secure the passage of the Meat Inspection Act (1906) and the Pure Food and Drug Act (1906). Roosevelt moved further to the left in the last years of his administration. However, after a panic in 1907 was halted by J. P. Morgan's intervention, Roosevelt allowed Morgan's U.S. Steel Corporation to absorb the Tennessee Coal and Iron Company in 1907, a move that added considerably to U.S. Steel's already impressive holdings. Despite his harsh attacks on the "malefactors of great wealth," the president remained indebted to Morgan, who still functioned as the national bank and would continue to do so until the passage of the Federal Reserve Act six years later. Roosevelt and Conservation Without dispute, Roosevelt's actions to conserve America's natural resources were one of his greatest achievements. He established six national parks, sixteen national monuments, and fiftyone wildlife refuges. He saved 150 million acres for future generations and, in so doing, angered most major business interests in the West as well as powerful members of Congress. In keeping with the Progressive Era's emphasis on scientific management, Roosevelt placed the conservationist Gifford Pinchot in charge of federal lands and resources. In contrast to preservationists, such as John Muir, who believed that the wilderness should remain in its natural state, conservationists advocated efficient use of natural resources and sought a managed approach to balancing the needs of industry with the need for preserving the natural world. Although preservationists fiercely opposed Roosevelt's conservationist policies, the most powerful opposition to Roosevelt's policies came from Congress, which finally put the breaks on his reform efforts in 1907. Nevertheless, Roosevelt managed to achieve much for the future of the nation's environment. Roosevelt the Diplomat In the area of foreign affairs, Roosevelt believed that the president should direct policy and the "civilized nations" should police the world. He used a combination of diplomacy and military strength to achieve his ends. In the Caribbean, Roosevelt protected the Monroe Doctrine, threatening Germany with war when the European nation tried to intervene to force the repayment of Venezuelan debts. His understanding of the position of the United States in the Western Hemisphere was made clear in his handling of the Panama Canal. After Colombia refused to sell the American government rights to the strip of land across the isthmus, Roosevelt implicitly backed a revolution in Panama in 1903, subsequently enabling the United States to negotiate and build a canal there. He created a policy, known as the Roosevelt Corollary to the Monroe Doctrine, declaring for the United States the role of "policeman" of the Western Hemisphere. He worked to create a high profile for the United States in the world by preserving the Open Door policy in China and helping to maintain a balance of power in Europe. He also negotiated an end to the Russo-Japanese War, winning the Nobel Peace Prize in 1906 for his accomplishment. While Roosevelt admired the Japanese and condemned the 1906 California legislation for segregated public schools for Asians, he discouraged Japan's growing aggressiveness by sending the U.S. navy's most up-to-date battleships on a world tour. Progressivism Stalled, pp. 770-774 Upon Roosevelt's retirement from office in 1909, his handpicked successor, William Howard Taft, assumed the duties of the presidency. Unlike Roosevelt, Taft was ill suited for the presidency, and his term was marked by progressive stalemate, a bitter break with Roosevelt, and a schism in the Republican Party. The Troubled Presidency of William Howard Taft In his first two years as Roosevelt's handpicked successor, William Howard Taft was ill suited for his job and easily influenced by the conservative wing of his party. He supported the PayneAldrich bill, which raised the tariff rate, calling it the "best bill that the Republican Party ever passed." He undid many of Roosevelt's conservation measures and badly split the Republican Party, enabling the Democrats to sweep the 1910 elections. Congress then took the lead in passing progressive legislation to regulate mine and railroad safety, establish an eight-hour day for federal workers, and create legislation initiating constitutional amendments for an income tax (Sixteenth Amendment) and the direct election of senators (Seventeenth Amendment). In foreign policy, Taft pursued a trade policy called "dollar diplomacy." Taft believed he could substitute "dollars for bullets" in American foreign affairs, not realizing that an aggressive commercial policy could not succeed without strong military backing. Consequently, to protect American interests abroad, he ended up sending troops into Nicaragua and Santo Domingo as well as to the border of Mexico. In the end, America's "dollar diplomacy" involved both dollars and bullets and proved most unpopular with the country's Latin American neighbors. In 1911, there was a breach between Taft and Roosevelt when the government filed an antitrust suit against U.S. Steel that cited Roosevelt's 1907 agreement with J. P. Morgan. An embarrassed Roosevelt began to hint that he might run for president again. Progressive Insurgency and the Election of 1912 Sensing Taft's weakness, Roosevelt decided to run for the Republican nomination. He lost but formed the Progressive Party, which nominated him on a platform called "The New Nationalism." It demanded woman suffrage, the direct election of senators, a federal income tax, conservation of natural resources, and workers' compensation, among other planks. The Republican-Progressive split opened the door to the Democrats, who nominated the governor of New Jersey, Woodrow Wilson, on a platform called "The New Freedom." Wilson's program of reforms, which were intended to appeal to small businessmen and farmers, pressed for lower tariffs, stronger antitrust legislation, and cheaper agricultural loans. The Republican vote was split, but the Democrats remained united, and Wilson won the election. All three candidates called themselves progressives, marking 1912 as the high tide of progressivism. Woodrow Wilson and Progressivism at High Tide, pp. 774-776 In 1913, Woodrow Wilson, the southern-born, one-term reform governor of New Jersey who had spent most of his life as a college professor and intellectual, became president. Wilson brought to the presidency a gift for oratory, a stern will, and an uncompromising nature. Before leaving office, he would enact not only his own platform of reforms but Roosevelt's as well. Wilson's Reforms: Tariff, Banking, and the Trusts Wilson spent his first months in office working on tariff reform. With the support of the House and progressive senators, the Underwood tariff passed, lowering rates by 15 percent and including a moderate income tax. Next, Wilson turned to reform of the banking industry, which the Pujo committee had shown controlled over $22 billion in assets nationwide. The call for banking reform was immediate and resulted in the Federal Reserve Act of 1913. It created twelve Federal Reserve banks, privately controlled but regulated and supervised by a Federal Reserve Board that was appointed by the president. It provided a larger degree of government control over banking and has been called Wilson's most significant piece of domestic legislation. Wilson supported the 1914 Clayton Antitrust Act, which was designed to define "unfair competition" and rescue labor from prosecution under the antitrust laws. During the passage of the Clayton Act, Wilson also supported the Federal Trade Commission Act. It set up a government commission to regulate trade by issuing "cease and desist orders" against "unfair trade practices." The appointments of the commissioners came from President Wilson, and as with the Federal Reserve Board, he appointed conservative businessmen to the board. Progressives were displeased with the appointments. Wilson, Reluctant Progressive After passage of his New Freedom measures, Wilson backed off from further efforts to enact reform legislation. Soon after the Republican gains in 1914, however, he realized that he needed to win over labor and voters from the Midwest and West. Consequently, he appointed labor favorite Louis Brandeis to the Supreme Court. Wilson also supported farm-credit legislation, workers' compensation legislation, and a child labor law. He had moved a long way from his position in 1912 to embrace many of the social reforms of Theodore Roosevelt. The Limits of Progressive Reform, pp. 776-784 Progressivism never was a radical movement. It was designed to reform and preserve the capitalist system. Its conservatism can be shown by comparing it with the more radical groups of the time or with groups left out of the process. Radical Alternatives Going beyond the progressives were the socialists, the Wobblies, and social activists, such as Margaret Sanger. Many members of the Socialist Party were middle-class, native-born Americans who drew as much on the social gospel as on Karl Marx. Socialist Eugene V. Debs ran five times for the presidency during the Progressive Era and called for a breakdown of the capitalist system, equality among all persons, and cooperation rather than competition. The most militant union in America was the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW), nicknamed "the Wobblies" and led by William Dudley "Big Bill" Haywood. The IWW advocated direct action, sabotage, and strikes to create an uprising of the working classes. Social activist Margaret Sanger, a nurse of middle-class background, spent her life advocating birth control and contraception as a movement for social change. Although contraception was then a radical and even illegal notion, Sanger published a contraception newspaper, opened the first American birth control clinic, and was jailed for her efforts. Progressivism for White Men Only Throughout the progressive period, women's call for the vote was rebuffed, but the cause of woman suffrage continued to be promoted vigorously. In 1916, Alice Paul founded the militant National Woman's Party (NWP), whose members advocated civil disobedience and concentrated their efforts on fighting for a constitutional amendment to provide woman suffrage. The less radical National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA), under the new leadership of Carrie Chapman Catt, implemented the "winning plan," a state-by-state strategy to keep suffrage momentum going all over the country. World War I provided the final impetus for woman suffrage. The NWP would not work for the war, but NAWSA did. In the end, a suffrage amendment became part of the Constitution in 1920, due to the contributions of both Paul and Catt; without the militancy of the NWP, the NAWSA would not have seemed moderate and respectable. In the West and South, many progressives saw racism as a form of reform. Pressured, Hiram Johnson, the progressive governor of California, signed the Alien Land Law in 1913 to keep the state's land in the hands of whites. The act was symbolic, since Japanese children born in the United States were citizens and could purchase land, but it showed that progressive politicians sometimes were willing to undermine their own principles in order to maintain their positions. In the South, progressives argued that black voting was a source of political corruption and the denial of the franchise to blacks a reform. They curtailed black voting rights by means of poll taxes and literacy tests; unfortunately, such measures also denied access to poor, illiterate whites likely to vote Populist. The era also saw the rise of "Jim Crow" laws, designed to segregate public facilities. Booker T. Washington, a former slave and black educator, preached accommodation with the white population and, in the "Atlanta Compromise," offered to accept segregation in exchange for economic progress. In 1896, the Supreme Court upheld the legality of segregation in the Plessy v. Ferguson case, which established that "separate but equal" facilities were acceptable. Roosevelt brought on controversy by merely inviting Booker T. Washington to dine with him at the White House, even though the two were discussing only politics and patronage, not civil rights. President Wilson, a southerner, allowed his postmaster general to segregate facilities "in the interest of the Negro." Educated blacks in the North, led by W. E. B. Du Bois, began to call for civil rights without accommodation. In 1905, Du Bois founded the Niagara movement, which helped found the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) in 1909. Like other progressive groups, the NAACP was a diverse group of white and black social workers, socialists, and intellectuals. Conclusion: The Transformation of the Liberal State Despite its limitations, progressive reform brought changes that moved the presidency and federal and state governments toward greater responsibility over the economy and social welfare. Progressive reform expanded the power of government and of American democracy, and it marked the beginning of the twentieth-century liberal state. World war, though, would mount a new challenge to progressivism in the coming years.